Negotiations↑

In December 1915 and March 1916, two French delegations led by Paul Doumer (1857-1932), and Albert Thomas (1878-1932) and René Viviani (1863-1925) respectively asked Tsar Nicholas II (1868-1918) to send Russian soldiers to France, which desperately needed more manpower on the Western Front, in exchange for an increase in war material deliveries. The tsar declared he wanted to help his allies but was sorely lacking the men to do so. Despite being also opposed to the project, General Mikhail Alekseyev (1857-1918) consented to send around 40,000 soldiers to fight in foreign theatres in exchange for war material. These troops came to be known as the Russian Expeditionary Force (or Corps in Russian literature) and were arranged in four special brigades (two for France and two for Macedonia). The decision to send Russian troops to the Balkans was in fact the implementation of a plan already suggested by Nikola Pašić (1845-1926) in 1914 and supported by the Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Sazonov (1860-1927), who believed that Russian presence in the Balkans would give Russia leverage in the postwar negotiations.

France↑

The First Russian Special Brigade consisted of two regiments and was formed in January 1916. Major-General Nikolai A. Lokhvitskii (1867-1933) was appointed as its commander. It reached Marseille in April 1916 after having traveled via the Trans-Siberian Railway to Dailan and then via boat through the Indian Ocean and Suez Canal to the Mediterranean. It was joined by the Third Special Brigade in August 1916. Both brigades fought at Verdun before being transferred to a quieter section on the front in Champagne.

In April 1917 Champagne became the ground of the bloody offensive conceived by the French Commader-in-Chief Robert Nivelle (1856-1924). Russian troops performed well, but both brigades suffered multiple casualties and were pulled out of the front and stationed in La Courtine Camp for rest and reformation. At this time, the news of the February Revolution, which was previously concealed by officers, reached the majority of Russian soldiers. As a result, a mutiny broke out. The soldiers formed Soviets and requested to be sent back to Russia.

Remarkably, at the early stage of the mutiny Russian soldiers were not protesting the war itself, but rather fighting away from their homeland. As the mutiny progressed, soldiers’ demands radicalized. The French command and the loyal elements of the Russian forces violently suppressed the mutiny in September 1917. Its leaders were arrested. Some were executed and some sent to prisons in France and North Africa. The mutiny and the news of the Bolshevik revolution magnified French concerns regarding the loyalty of the Russian soldiers. The brigades never returned to the frontline.

Macedonia↑

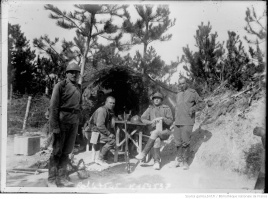

Immediately after arrival in Salonika in August 1916, the Second Russian Brigade, under command of Major-General Mikhail K. Diterichs (1874-1937), was sent to the frontline near Florina. There, Russian soldiers took part in the fighting against the Bulgarians, along with their French and Serbian allies. After taking the city on 17 September 1916, they were joined by the Fourth Brigade. Both units were involved in the capture of Monastir (now Bitola) in December. During winter of 1916-1917 they held the line along the Cerna River and waged a mountain war of coups de main.

The news of the February Revolution did not cause great trouble in the ranks of the Second and Fourth Brigades. The soldiers were sworn into the new government peacefully. Due to the constant deficit of manpower on the Salonika Front, the brigades also contributed to several actions in Greece, including the forced abdication of King Constantine (1868-1923) when allied forces seized Athens in June 1917. Petrograd also took advantage of other actions in Greece to assert their influence in contested areas, for example the orthodox monasteries on Athos Mountain.

After their participation in the May offensive, the brigades were assigned to new positions around Prespa Lakes. As in the rest of the Russian army and Russian brigades in France, Soviets were formed. Soldiers asked for clarification of the reasons for their presence in Greece and soon enough asked to go back to Russia. War weariness, lack of permissions, Bulgarian propaganda, and finally the news of the Bolshevik coup caused mutinies in November and December 1917. Following the mutinies, French General Adolphe Guillaumat (1863-1940) decided to finally remove Russian troops from the frontline.

After 1917↑

After the mutinies in La Courtine Camp and Macedonia, Russian soldiers were split into three categories: loyal elements that were willing to continue to fight; soldiers unwilling to fight but ready to become workers in France or Greece; and those unwilling to fight or work.

The first category formed the Russian Legion of Honour (Légion Russe pour l’Honneur), a few hundred-strong units that continued to fight with the French army until 1918. It was part of the French Morroccan Division under command of General Daugan (1866-1952). It took part in the Second Battle of the Marne in July-August 1918 and in November-December 1918 was a part of the first French occupying troops in the Rhineland.

The second category was scattered across farms and factories in France, while the third category suffered the harshest treatment: soldiers were organized in forced labor battalions and were predominantly sent to Northern Africa.

Once the war was over, the question of repatriation of the Russian soldiers was raised. Most were gradually sent back by the French government in 1919-1921. Most of the officers and about 3,000 soldiers chose to remain in France rather than to return to Soviet Russia.

Memory of the REF↑

Russian soldiers sent to fight in foreign lands for Imperial Russia’s allies were an important political gesture that was later widely recalled both in France and in Soviet Russia.

The beacon of REF remembrance in France was the Association of Russian Officers - Veterans of the French Front. It took care of the cemetery for REF soldiers in St Hilaire-le-Grand. Appealing to the fact that the Russian legion kept fighting for France even after the revolution, the Association presented the soldiers as a part of Imperial Russia that kept its promises to the Allies. This image has persisted in Russian emigration historiography.

In Soviet Russia veterans also formed an Association of Former Soldiers of the Special Russian Brigades in France and in the Balkans, but it promoted very different values from its French counterpart. Supported by the Soviet government, the association tried to portray France as a “treacherous ally” that paid for its imperialist interests with the blood of Russian soldiers.

Even today, the memory of the REF continues to be politicized. For instance, in France there are two separate memorial associations dedicated to the memory of the Russian soldiers in France and the munity in La-Courtine respectively, which lean to either monarchist or socialist views.

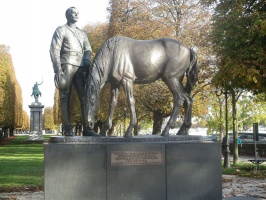

In Russia the image of the REF is now often used to highlight Russia’s ties to France. In 2011 Russian President Vladimir Putin and French Prime Minister François Fillion unveiled a memorial to the REF at Place du Canada in Paris.

Sofya Anisimova, University of St. Andrews

Gwendal Piégais, Université de Bretagne Occidentale

Section Editor: Nikolaus Katzer

Selected Bibliography

- Adam, Rémi: Histoire des soldats russes en France, 1915-1920. Les damnés de la guerre, Paris 1996: L'Harmattan.

- Anisimova, Sofya: Russian Expeditionary Force in memory and commemoration. Comparative case-study of Soviet Russia and Russian emigration in France, in: First World War Studies 10/2-3, 2019, pp. 187-205.

- Cockfield, Jamie H.: With snow on their boots. The tragic odyssey of the Russian Expeditionary Force in France during World War I, New York 1998: St. Martin's Press.

- Danilov, Yuri N.: Russkie otriady na frantsuzskom i makedonskom frontakh 1916-1918 g.g. (Po materialam Аrkhivov Frantsuzskogo Voennogo Ministerstva), Paris 1933: KIG.

- Malinovskiĭ, Rodion: Rodion Ia. Soldaty Rossii, Moscow 1968: Voenno Izdatelstvo.

- Pavlov, Andrei: 'Russkaia odisseia' epokhi Pervoi mirovoi. Russkie ekspeditsionnye sily vo Frantsii i na Balkanakh, Moscow 2011: Veche.