Origins↑

Local Public Organs↑

The All-Russian Union of Zemstvos and the Union of Towns were core elements of civic mobilisation for the war effort in Russia. Provincial and district zemstvos and town councils, or dumas, were organs of local self-government introduced into the Russian Empire in 1864 by Alexander II, Emperor of Russia (1818-1881) to manage local economic welfare. They were composed of deputies elected by the local population and employees from the professional intelligentsia, such as doctors, teachers, statisticians and agronomists, who came to be known as the "third element". Their jurisdiction included securing food supply, administering charitable relief, developing trade and industry, participating in public education and health, cooperating in preventing cattle disease and crop destruction and collecting taxes to spend on road upkeep and institutions of local justice.

Government statutes, however, limited the popular representation and decision-making power of these organs. Property qualifications built into the voting system, supplemented in 1890 by arrangements grouping voters by estate and depriving the peasants of the right to elect deputies directly to district assemblies, ensured the domination of the nobility among representatives. While certain local matters were transferred to the zemstvos, control over administration and policing remained in the hands of appointed governors subordinate to the ministry of the interior. Liberal gentry were disappointed in their desire for units below the district level to provide a foundation for zemstvo work through day-to-day contact with village life and for a national elected zemstvo organisation to coordinate their efforts. In practice, nevertheless, the public institutions were able to add to their sphere of competence, particularly in times of national crisis. During the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05, zemstvo representatives created a general organisation for the relief of sick and wounded soldiers and the first all-Russian congress of zemstvos met in November 1904, adopting an appeal to the Tsar for constitutional reform that was taken up by opposition groups in the 1905 revolution.

Wartime Rallying↑

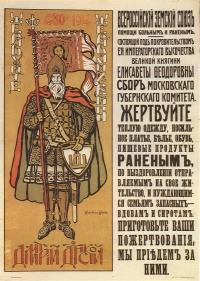

On 25 July (7 August) 1914, six days after the German declaration of war on Russia, an emergency session of the Moscow provincial zemstvo pledged its energies to the war effort and suggested an empire-wide association of zemstvos to organise medical aid. Less than a week later, a conference of delegates from thirty-five provinces resolved to create the All-Russian Union of Zemstvos, under the leadership of Prince Georgii Evgen’evich L’vov (1861-1925), approved by imperial decree on 15 August (28 August) 1914. At the same time, Moscow’s town duma fashioned the Union of Towns as a voluntary association of municipalities engaged in medical relief. In spring 1915, as defeats on the Galician front revealed the scale of the crisis in munitions supply, the joint Union of Zemstvos and Towns, known as Zemgor, was established to assist in supplying the army. The unions raised money for their activities through contributions from their provincial organisations and donations from private sources all over Russia. These funds became vastly outweighed, however, by sums disbursed from the state treasury and payments for state orders, so the unions were simultaneously organs of self-mobilisation and tightly intertwined with state structures.

Scope of Efforts↑

The tsar approved modest initiatives by the town and zemstvo unions. They were to last for the duration of the war to convey the sick and wounded from railway centres behind the army’s rear to hospitals across the country for treatment, under the flag of the semi-official Red Cross. By 1916, however, their activities had expanded considerably by virtue of the scale of the tasks at hand, the ineptitude of the central government, ambiguities in the unions’ remits and the ambitions of their personnel, until they were responsible for thousands of employees and monthly budgets of tens of millions of rubles. The presence of zemstvos in the vicinity of the front meant the unions were soon cooperating with the army to deal with streams of casualties in the war zone itself. The demands of equipping hospital trains and buildings, meanwhile, involved them in matters of supply and manufacture.

The fact that the unions were never properly legalised put them in a precarious position but also freed them from statutes that ordinarily restricted the operation of local self-government organs. Their work in the towns and provinces was generally directed by ad hoc committees whose membership comprised not only zemstvo and town duma boards but also a range of specialist professionals. Union regulations did not impose strict control over committee activities, merely requiring they be carried out in accordance with local conditions. This gave them the flexibility to assume a range of functions inadequately fulfilled by the state, such as providing relief for families of mobilised men, war orphans and refugees, conducting vaccination programmes, assisting agricultural production and intervening in food and labour supply and army provisioning.

The central government, however, remained ambivalent about this independent initiative and concerned about the political colouration of the unions’ professional employees. In the course of 1916, the regime curtailed union meetings, many workers left the committees and field operations fell off. Members of the union leadership began to agitate for a government of public confidence, as proposed by the Progressive Bloc in the national parliament, the State Duma, to resolve the problems facing the country. Following the February revolution in 1917 the head of the Zemstvo Union, Prince L’vov, became Prime Minister of the new Provisional Government, the unions were restructured and zemstvo boards became the official repositories of government power in the provinces, but they could not hold back economic disintegration and social polarisation and did not survive the Bolshevik seizure of power in October 1917 and the ensuing Civil War.

Achievements↑

Assessments of the unions of zemstvos and towns vary. Early accounts, influenced by recollections of leading union personnel, presented them as powerful organisations, possessing the confidence of the population and the army, whose largely successful wartime work was undermined only by financial constraints and government hostility. Later historians, such as Michael Hamm and William Gleason, began to point to inadequacies in union contributions, internal divisions between politically radical employees and conservative elites on local committees and indifference among the mass of the population. The story of the union leadership was at times conflated with that of the Duma and related as one of excessive caution on behalf of Russia’s ineffectual moderate liberals in the face of mounting political, social and economic crises.

Since the late 1970s, interpretations have become more nuanced, emphasising the heterogeneity of attitudes within the unions, the government and the population to the role of these organisations and the mixed results of their programmes. Cooperation between government and unions was possible and, thanks to the dynamism of union staff, more than 3,000 hospitals were established, an adequate ambulance service from the front existed, tens of thousands of refugees were fed, clothed and registered, and thousands of orphans were housed. They achieved much in the supply of meat to the army and the distribution of prisoners of war and refugees to compensate for agricultural labour shortages. Their contribution to munitions provision, however, was less significant and they added to the organisational chaos underlying the crisis in food supply.

The burdens of servicing the war effort, meanwhile, devastated the capacity of local organs to meet increased demand among the civilian population for information, schooling, healthcare provision and mitigation of the soaring cost of living. Ultimately, the structures linking civic organisations, state and population mobilised by all combatants in the war were not deeply enough entrenched in Russia. The unions represented both the climax of the participation of self-government bodies and the professional intelligentsia in national life and its demise.

Siobhan Peeling, University of Nottingham

Section Editors: Yulia Khmelevskaya; Katja Bruisch; Olga Nikonova; Oxana Sergeevna Nagornaja

Selected Bibliography

- Fallows, Thomas: Politics and the war effort in Russia. The union of Zemstvos and the organization of the food supply, 1914-1916, in: Slavic Review 37/1, 1978, pp. 70-90.

- George, Mark: Liberal opposition in wartime Russia. A case study of the town and Zemstvo unions, 1914-1917, in: The Slavonic and East European Review 65/3, 1987, pp. 371-390.

- Gleason, William E.: The All-Russian union of towns and the politics of urban reform in Tsarist Russia, in: Russian Review 35/3, 1976, pp. 290-302, doi:10.2307/128405.

- Polner, T. I. / Obolenskiĭ, V. A. / Ti︠u︡rin, Sergeĭ Petrovich: Russian local government during the war and the Union of Zemstvos, New Haven; London 1930: Yale University Press; H. Milford.