Introduction↑

In spite of the global turn in First World War historiography, the colour of the Great War and modern literary memory, to adapt the title of Paul Fussell’s (1924-2012) celebrated book, remains predominantly white. Eurocentrism however is no longer the only cause. Most of the colonial troops – the Indian sepoys, the Senegalese tirailleurs or the South African labourers – came from nonliterate or semiliterate communities and did not leave behind an abundance of journals, memoirs, poems, and novels. In such a context, how can we speak about colonial literatures of the war? Yet, it is indeed to our peril if we confuse the non-literate with the non-literary: the villages in Asia, Africa or the South Pacific from where these colonial soldiers came often had rich oral cultures where the “literary” was diffused through a variety of forms, from everyday prayers, chants and songs through verse recitations and storytelling to heightened speech rhythms.

Therefore, any effort to decolonize the First World War literary canon involves a two-fold shift: a redefinition of the very idea of “literature” with its implicit textual bias, as well as a reconceptualization of what we mean by “war literature”. Recovering and investigating South Asian literature of the First World War is not just a process of “adding to” or “expanding” the Western canon but involves putting pressure on what constitutes the “literary”: we need to embrace the oral and the aural along with what was written or published. Second, war literature cannot be reduced any longer to combatant literature alone. Literary historians often search for an Indian Wilfred Owen (1893-1918) or a Pakistani Siegfried Sassoon (1886-1967) in a mimicry of the English trench poet. But the contexts were very different: like colonial war memory, war literature in South Asia is far more oblique and diffused across the civilian sphere, filtered through or interrupted by other conflicts. Finally, in societies as multi-ethnic, multi-lingual and multi-religious as undivided India, literature flourished in different vernacular languages and followed different traditions.

State of Research and Sources↑

Four million non-white men were involved in the First World War. Of all the colonies of Europe, undivided India (India, Pakistan, Myanmar and Bangladesh), along with Sri Lanka and Nepal, contributed the highest number of men.[1] More than a million Indians, including 600,000 combatants and 450,000 non-combatants, served in places as diverse as France and Flanders, Mesopotamia, Gallipoli, East Africa, Persia, Egypt and Palestine.[2] In recent years, there has been a burgeoning interest in recovering the military and socio-cultural experiences of the South Asian troops and combatants. Following the publication of David Omissi’s fine volume of letters – Indian Voices of the Great War (1999) – and his socio-military account The Sepoy and the Raj (1994), there have been a number of excellent military, socio-economic and cultural accounts of India’s war involvement from historians.[3] Yet, the literary dimension of the Indian war experience has received scant attention.[4] While researching India, Empire, and First World War Culture. Writings, Images, and Songs (2018), the first literary and cultural study of the Indian war experience, I was constantly surprised to find, over a decade, a varied and powerful body of literary works – from both combatants and non-combatants, men and women – that straddles the genres of memoir, verse, fiction, short story, plays and songs.[5] Such a body of work was crucial in at least two respects: it was the recovery of a rich literary tradition as well as of a lost continent of experience, both at home and overseas. In a context where historical sources are pitifully scarce, literature, I argued, filled in the gaps of history and bore testimony to the country’s complex and often contradictory relationship to the war. Such a recovery was the first step towards a more global literary memory and opened up a rich representational space to capture the undertones, emotions and nuances of a conflict that reverberated in the furthest reaches of the empire.

Combatant and Non-combatant Literature: Letters, Songs, Memoirs and Poems↑

A poignant photograph from the Imperial War Museum (see the image “Letter-writing in Brighton”) shows a non-literate sepoy dictating a letter to a scribe: this is how letters were often composed. The original letters are now lost, but hundreds of extracts from them, translated by the colonial censors, survive. Neither the direct transcript of trench experience nor just scribal embellishment, they are some of the earliest encounters between textual form and South Asian subaltern history. These sepoys might have been non-literate but they were intensely literary; there is a thickening of language as emotions such as horror, resignation, or homesickness erupt through images, metaphors, and similes:

The images of “dry forest in a high wind” or “tired bullocks” show how the cognitive and affective processes of these men were still shaped by the agrarian culture of Punjab. These letters, often treated as linguistic bubbles on the sea of plebeian history, are rooted in the robust oral culture of Punjab:[7] a whole generation of men who had grown up listening to myths, legends, and qissas (“stories”) in Punjabi are now forced to write or dictate letters shaped by these narrative traditions. They can be read alongside the very popular if propagandist Urdu journal Akbar-I-Jung for wounded Indian troops convalescing in various hospitals in south England or, more productively, with the recently unearthed qissa, Vada Jung Europe (The Great European War), a 2,000-line verse narrative meant to be recited or sung. Written in Gurmukhi by “Nand Singh Havildar” [Havildar means a junior military post] in 1919, it is of uneven poetic quality, often little more than a catalogue of names, dates and events, interrupted by reflections or scenes of immense poignancy, as in the following description of the battlefield:

Similarly, the delicate bodies of soldiers lie in the battlefields,

Their long hair reminded people that they were Sikhs, ...

The white had pretty skin. They were in the prime of their youth.[8]

The long narrative ends with a plea – “Listen, O Master, listen to my prayer, O God, stop this bloody battle”. At once a battle-chronicle, a religio-philosophical meditation and an elegy for lost youth, the poem remains a singular document.

We have insights into some of these rich oral cultures through an extraordinary archive of 2,677 sound-recordings of prisoners of war held at Wünsdorf, including some 300 South Asian ones, made by the Royal Prussian Phonographic Commission between 29 December 1915 and 19 December 1918.[9] The men were made to stand in front of a phonograph and asked to read out a text, narrate a story, or sing a song; they were also measured, photographed and studied as part of an ethnological study at the time. One of the most poignant recordings is by a twenty-two-year old Gurkha sepoy Jasbahadur Rai. Consider the following extract:

We arrived in the country, Germany, at the orders of the British

Listen, oh listen, gold-wearing birdie, at the orders of the British

Listen, oh listen, gold-wearing sister, the heart cries, sobbing.

The bubbling of water, the restlessness of this heart, how many days will it take to console yourself?[10]

Blurring the boundaries between reportage, lament, and compulsive testimony, the song is also the birth of the lyric subject as the Nepalese genre of jheyru or female lament is called upon to bear witness to historical trauma. This grainy recording, with the high-pitched and desolate voice rising and falling, gives a certain material poignancy to Gayatri Spivak’s famous rhetorical question: “Can the Subaltern Speak?”

But what about literature with a capital L? Much of the important literature is in the regional languages. Though the Bengalis were barred from joining the army and served as non-combatants, a disproportionately high number of memoirs come from them. The most powerful of them is Abhi Le Baghdad (On to Baghdad) (1957) by a middle-class Bengali youth, Sisir Prasad Sarbadhikari, who worked as a stretcher-bearer in Mesopotamia and was caught up in the siege of Kut before being taken prisoner and dragged across the Middle East.[11] Deeply literary and immensely powerful, it bears traumatised testimony to the war in the Middle East – from the aftermath of the Battle of Ctesiphon, through the horrific five-hundred-mile-long forced march to Ras al-Ayn or the witnessing of the Armenian Genocide, to a rich world of transnational friends – with fellow Indians, wounded Turkish soldiers and terrified Armenians – in a hospital in Aleppo. The other remarkable Bengali memoir is Kalyan Pradeep. The Life of Dr Kalyan Kumar Mukopadhyay (1928) by an eighty-year-old woman, Mokkhada Devi, about her only grandson – trained in the United Kingdom and part of the distinguished Indian Medical Service – who served as a doctor in Mesopotamia and died in captivity.[12]

The only major literary figure from undivided India who joined the army (the 49th Bengali) and underwent military training (though his battalion was never mobilized) was the Bengali rebel-poet Kazi Nazrul Islam (1899-1976) – now regarded as the national poet of Bangladesh.[13] Nazrul was an anti-colonial revolutionary poet with socialist sympathies but joined the imperial war effort. He wrote a number of war stories, such as Henā (1919), Vyathār Dān (1919), Rikter Vedan (1924), an epistolary novel called Bāndhan-Hārā, and a number of poems. What is remarkable about his war writings is the way the First World War gets fused with other events such as the October Revolution, the Third Anglo-Afghan War, and the Indian nationalist struggle to form a vision of revolutionary violence, incandescent for him with a terrible beauty. His most sustained poetic effort around the war is his long poem Śāt-il-Ārab, which reveals his deeply conflicted feeling about the Indian participation in the Middle East, particularly against fellow Muslims:

Is now filled with the blood shed at Amara;

The disgorged blood dances in you, Tigris, in a terrible drunkenness

The restless waters of the bloodied river, the Euphrates, roar

“I have punished the insolent!”

…

The battalions of Iraq! This really is some story.

Who would have known here one day the Bengali forces

Would cry “Mother mine!”, burning with tears at your sorrow, …

Land of martyrs! Farewell! Farewell!

This wretched today bows his head to you.[14]

A poem on imperial conquest becomes an elegy for the subjugated motherland: the Turks and Arabs are hailed as shahid (martyrs) and azad (liberators), fighting for freedom. The lines of identification are clear. The empathy that men such as Kalyan Mukherjee and Sisir Prasad Sarbadhikari felt with the local people and the resulting ambivalence about the Indian role in Mesopotamia reach a shattering climax in this Muslim anti-colonial revolutionary poet.

The Home Front: Propaganda, Pamphlets and Protest↑

When war was declared, the responses in India were largely enthusiastic: even nationalist leaders, including Mahatma Gandhi (1869-1948), threw themselves into the recruitment effort. Contribution to the war, it was widely believed, would be rewarded with greater political autonomy. Punjab was the main recruiting area and contributed more than half the total number of combatants from the subcontinent. Punjabi folk literature, particularly verse and songs, were mobilized by the colonial officials and local chieftains for recruitment purposes. New songs were commissioned, such as the following, called “Rang-Root”:

Here you get broken slippers, there you’ll get full boots, get enlisted,

Here you get torn rags, there you’ll get suits, get enlisted,

Here you get dry bread, there you’ll get biscuits, get enlisted.[15]

While this rich sonic world has been lost, what had survived, I realised in the course of my research, was a powerful corpus of printed war texts in Punjabi and Urdu published across northern India, particularly in Punjab. These range from recruitment verses such as Bharti. On Recruiting (1915) and Nara-e-Jung (1918) to historical treatises and pamphlets, including Fasānah-i-Jang Yurap (The Story of the European War) (1914), Jarmani ke asli Halat (The Real Condition of Germany) (1915) and Haqiqat-i Jang (The Truth of the War) (1915). Most probably, they were commissioned by the colonial state but several of them have a deeply subversive streak. Consider Bahār-i-Jarman (1915), an anthology of short and satiric war poems in Urdu published in Moradabad:

Holi brought youth in the old age, the merchant (seth) is playing Holi with another merchant

Why should the nephew not be shocked, Uncle starting to play Holi with aunty.

The War in Europe has caused so much devastation, times are not peaceful, nor is Holi sweet.

Rivers of blood are flowing in Europe, in what new colours has arrived the old Holi.[16]

Comedy, critique and domestic detail are combined as the festival of Holi is reframed first as a family sport between uncle and aunt and then between greedy merchants (“Seth se khelne ... hai sethani holi”), hinting at the interpretation of the war as frivolous sport between capitalist nations, fattening on colonial plunder.

In wartime Punjab, the most powerful form of literary dissent against the imperial war effort was to be found in the pages of Ghadar di Gunj (1914), the poetry and literature of the Ghadar movement. “O men in arms why are you supporting my oppressors”, queries Mother India in a poem called The Cry of the Motherland to Her Soldiers.[17] However, its protest was against empire rather than against warfare; in fact, it was a parallel call to arms. But there were a number of war pamphlets, such as Fasānah-i Jang-i Yurap (The Story of the War in Europe) (1914) mentioned above, which were possibly commissioned as anti-German propaganda but which end up denouncing the war itself:

The apocalyptic imagery recalls the tradition of Marsiya, Nūhah and Soz – elegiac laments sung for the martyrs of Karbala. A generic mythic imagination about warfare evolves into a visceral description of industrial warfare one would expect in the writings of Owen or Henri Barbusse (1873-1935). What makes it remarkable is that it would be produced as early as 1914 by two civilian Indian writers who had never left the country: Piyare Mohan Datttatreya, a celebrated student of philosophy and economics at the Government College of Lahore and Bishan Shahi Azad, a well-known Urdu journalist.

However, some of the most eloquent protests came from the village women whose fathers, husbands or sons had actually left for war. Poor, non-literate and disenfranchised, the voices of these women are wholly absent in the conventional archives or narratives. But what have serendipitously survived are folksongs improvised and sung during the war years by these women. Coaxing, cajoling, anxious, passionate, rueful, angry, desperate, mournful, bitter and desolate in turns, these folksongs provide us with a veritable archive of female emotions, pointing to a buried tradition of female protest:

All have gone to laam. [l’arme]

Hearing the news of the war

Leaves of trees got burnt.

Without you I feel lonely here.

Come and take me away to Basra.

I will spin the wheel the whole night.

………………………………………………..

War destroys towns and ports, it destroys huts

I shed tears, come and speak to me

All birds, all smiles have vanished

And the boats sunk

Graves devour our flesh and blood.[19]

The Punjabi poet Amarjit Chandan, who has translated many of these songs, calls them “the voice-overs of historical events”.[20] These are subaltern songs of protest: in a context where almost nothing is known about women’s responses, these songs pierce the silence.

Elite Literature: from Tagore and Guleri to Anand and Shamsie↑

Much of the surviving war literature was produced by the educated middle-classes and the political bourgeoisie. It ranges from essays, poems, and short stories to fiction, both in English and vernacular languages. Some of them were published in English-language journals, such as the short-lived Calcutta-based Indian Ink (1914-1916) and the compendious war volume All About the War in India (c. 1915), published from Madras. The most remarkable contemporary Indian voice in English was that of Sarojini Naidu (1879-1949): internationally feted poet, as well as feminist, nationalist and future leader of the Indian National Congress. Educated at King’s College London and publishing from London, she was christened “Bharat Kakila” or the “Nightingale of India” by Gandhi and praised by critics in Britain as well for her mellifluous verse in English. Consider the following extract from her poem The Gift of India written for the Hyderabad Ladies War Relief Association in December 1915 and collected in The Broken Wing. Songs of Love, Death and Destiny 1915-1916:

Silent they sleep by the Persian waves.

Scattered like shells on Egyptian sands

They lie with pale brows and brave, broken hands.

They are strewn like blossoms mown down by chance

On the blood-brown meadows of Flanders and France.[21]

The most articulate of Indian women-nationalists seems to be ensconced in the English patriotic and pastoral tradition through colonial education. Images such as “pale brows,” the euphemistic “blossoms,” and the labials and sibilance show a shared Georgian heritage with poets such as Owen. But Naidu’s poem is also the English war lyric turned upside down as she at once inherits and interrogates the stock images of Victorian verse. In the poem, the nation is not Britannia but “Mother India” as she calls on the empire to remember and honour her colonial subjects who lie “strewn” on the “blood-brown” – not blood-red – battlefields: “Remember thy martyred sons!”. For Naidu, the imperial war service becomes the route not just for greater political autonomy but a validation of Indian racial and nationalist honour, a recurrent theme in writings of the time with regional variations. Thus, in the Bengali recruitment play Bengali Paltan written by Satish Chandra Chattopadhyay and produced in Kolkata in 1916, the war is portrayed as a test for Bengali masculinity: “Who calls me now a coward base/And brands my race a coward race?”[22]

This complex relationship between war service and racial and nationalist honour finds one of its subtlest expressions in the short story Mutiny by Naidu’s fellow feminist and writer Swarnakumari Devi (1855-1932), who was also the sister of the celebrated Indian poet and Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941).[23] Part reminiscence, part story, part critique, it sets India’s war contribution against memories of the Sepoy Mutiny to explore the relationship between British paranoia, racism and class, and expose the hypocrisies within British liberalism – all within the setting of a dinner party where a group of upper-class English and Indian women socialise. Very different in subject and tone but similarly fraught is the immensely popular short story Us Ne Kaha Thah (At Her Bidding) (1915) which catapulted its author Chandradhar Sharma Guleri (1883-1922), a Sanskrit scholar and school teacher, to literary stardom.[24] The story is a “first” in several senses: it is the first short story in Hindi, as well as the first short story to evoke the trench warfare from the perspective of the Indian sepoy, as it joins its blood-dimmed history to the story of love and sacrifice in a small village in Punjab. Neither pro-war nor anti-war, the story neither affirms or dissents as Guleri evolves traumatic historical experience into an intimate story of heroic self-sacrifice, personal honour and religious self-fashioning through the figure of Lehna Singh, a Sikh soldier. Many of the tropes we associate with European trench narrative – trench raids, mud, darkness, ribald humour, same-sex intimacy – are present in this remarkable story by an aging civilian teacher who had never been outside India.

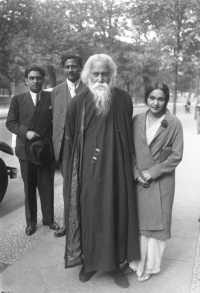

The three Indian intellectuals who were most visible on the international stage were Tagore, Muhammed Iqbal (1877-1938) and Mulk Raj Anand (1905-2004). All three were anti-colonial but Tagore, alone among most Indian intellectuals, was also fiercely anti-nationalist. After receiving the Nobel Prize in 1913, he became one of the most feted literary figures, lecturing to packed audiences from Japan and Germany to Argentina; Owen read his prize-winning poetry collection Gitanjali in the trenches. Some of Tagore’s poems were coopted for imperial propaganda and published in The Times in 1915 alongside those of Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936) and Laurence Binyon (1869-1943). But The Oarsmen reveals his mature stance on the war which, for him, was the symptom of a greater spiritual malaise:

The heat growing in the heart of God for ages—

The cowardice of the weak, the arrogance of the strong, the greed of prosperity,

the rancour of the deprived, the pride of race, and the insult to man—

Has burst God’s peace, raging in storm.[25]

In his celebrated lectures on nationalism, delivered in Japan and the United States respectively in 1916, he launched one of the most sustained and searing critiques of industrial modernity, capitalism and nationalism whose unholy nexus, for him, had led to the global catastrophe: “In this frightful war the West has stood face to face with her own creation, to which she had offered her soul”.[26] These essays – in which the argument is conducted through metaphors and allusions – collapse the boundaries between philosophy, politics and literature and were deeply controversial at the time. As with Virginia Woolf (1882-1941) in Three Guineas, empire, nation-building and war were, for Tagore, related in a vicious cycle of violence. Back in India, Tagore would be joined by Iqbal from Punjab, one of the greatest Muslim poets and thinkers from South Asia. Trained in philosophy in Cambridge and Heidelberg, Iqbal, like Tagore, was anti-colonial but no simple critic of the West; its literature and culture had partly shaped him.[27] Yet, like Tagore, the war made him doubt “whether the torch of European civilisation was not meant for showing light but to set fire”.[28] In 1922, he would publish a collection of poems in Persian called Payam-i-Mashriq (A Message from the East), which included the following poem:

In this as in so many other fields

Fine are the ways it kills,

And great are its skill’s yields.

…

Its submarines are crocodiles

With all their predatory wiles.

Its bombers rain destruction from the skies.

Its gases so obscure the sky

They blind the sun’s world-seeing eye.

Its guns deal death so fast

The Angel of Death stands aghast,

Quite out of breath

In coping with this rate of death.

Despatch this old fool to the West

To learn the art of killing fast – and best.[29]

Here, the English metaphysical poet John Donne's (1572-1631) love of conceits, as in The Sun Rising, is combined with the wit of the Indian Muslim poet Akbar Illahabadi (1846-1921) to produce biting satire. Such a mode puts pressure on our very idea of First World War verse: the pity and pathos of Owen are instead replaced by a sharp dose of anti-colonial and anti-Western schadenfreude. Both Tagore and Iqbal hoped that the global catastrophe might usher in a more just and equitable world-order. But such hopes would be swept aside, first by Versailles and then the Amritsar Massacre of 1919, which made Tagore give up his knighthood in protest.

However, to understand the emotional world of the sepoys, one must turn to Mulk Raj Anand’s Across the Black Waters – the only Indian “war novel” (1939). Anand grew up in the Punjab but came to London and established himself as a cosmopolitan intellectual on the fringes of the Bloomsbury group. The novel is dedicated “to the memory of my father Subedar Lal Chand Anand, M. S. M., (late 2/17th Dogra)” who worked in the British Indian army. The middle novel in the Lalu trilogy, Across the Black Waters opens up a whole new world in war fiction, as we see the protagonist Lalu and his fellow sepoys from a Punjabi village arriving in Marseilles:

“We have reached Marsels!”

“Hip, hip, hurrah!”

The sepoys were shouting excitedly on deck.

Lalu got up from where he sat watching a game of cards and went to see Marseilles.[30]

For the writer of “pidgin English”, linguistic and cultural difference is inscribed in the very opening word through the robust (mis)pronunciation. Anand is one of the first Indian writers to launch a sustained experimental attack on standard English. Following in the footsteps of Owen and Erich Maria Remarque (1898-1970), Anand gives us the trench experience in both its gory detail and intense male bonding. But the delicacy of the novel lies in the way he exposes the weight of colonial history in the intimate regions of the self as internalisation of the racist ideology:

But the war becomes for Lalu a site of politicisation as he begins to question both colonial and racist hierarchies. Anand’s novel, in this sense, is an important corrective to Kipling’s propagandist The Eyes of Asia (1917), where Kipling imagines himself to be an Indian sepoy writing back home about the glories of empire and Europe. More importantly, Across the Black Waters finds a voice for the working-class Indian sepoy, a tradition that has been carried forward in British-Pakistani novelist Kamila Shamsie’s recent novel A God in Every Stone (2014). Shamsie combines historical thickness with postcolonial and queer insights, as she layers the war experience with the history of the country’s nationalist struggle.

Like the experience of the South Asian troops, there is no homogenous literature from undivided India. A hundred years after the conflict, what surprises us is the power and diversity of this body of literature, from the folk-songs of non-literate village widows to Naidu’s poems in English or Tagore’s lectures on nationalism delivered around the world. While they are testimony to the very different “home fronts” and war fronts – nuanced to class, caste, gender and combatant/non-combatant status, among others, they also point to the vitality and diversity of literary production and how it illuminates the fault lines of history.

Santanu Das, All Souls College, University of Oxford

Reviewed by external referees on behalf of the General Editors

Notes

- ↑ See Introduction, in: Das, Santanu (ed.): Race, Empire and First World War Writing, Cambridge 2009, p. 4. This essay is also based in part on Das, Santanu: South Asian Literature of the First World War, in: Cohen, Debra Rae / Higbee, Douglas (eds.): Teaching Representations of the First World War, New York 2017.

- ↑ Statistics of the Military Effort of the British Empire during the Great War, 1914-1920, London 1920, p. 777.

- ↑ For a select list of the important monographs and volumes in this burgeoning field, see the selected bibliography.

- ↑ The notable exceptions are sections in Higonnet, Margaret (ed.): Lines of Fire. Women Writers of World War I, New York 1999; Buck, Claire: Conceiving Strangeness in British First World War Writing, Basingstoke 2015; and Das, Santanu (ed.): Cambridge Companion to the Poetry of the First World War, Cambridge 2014.

- ↑ Many of the works addressed here are discussed in greater detail in my monograph, Das, Santanu: India, Empire, and First World War Culture. Writings, Images, and Songs, Cambridge 2018.

- ↑ The extracts from the letters, housed in the British Library, London, are quoted in Omissi, David: Indian Voices of the Great War. Soldiers’ Letters, 1914-18, London 1999, p. 77, 91.

- ↑ See Mir, Farina: The Social Space of Language. Vernacular Culture in British Colonial Punjab, Berkeley 2010.

- ↑ Singh, Nand: Vada Jung Europe [The Great European War], Ludhiana 1934, p. 18. Written in 1919. Translated by Arshdeep Singh Brar.

- ↑ See Ahuja, Ravi / Liebau, Heike / Roy, Franziska (eds.): “When the War Began, We Heard of Several Kings”. South Asian Prisoners in World War I Germany, Delhi 2011.

- ↑ Rai, Jasbahadur: Song, The Sound Archives of the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, PK03080100. Translated from Nepalese by Anne Stirr. Also see Das, Santanu: Reframing Life/War Writing, in: Textual Practice 29/7 (2015), pp. 1265-1287 and Lange, Britta: South Asian Soldiers and German Academics in: Ajuha et al., When the War Began 2011, pp. 148-184.

- ↑ Sarbadhikari, Sisir Prasad: Abhi Le Baghdad [On to Baghdad], Kolkata 1957. See Das, India, Empire, and First World War Culture 2018, pp. 255-273. Also see the wonderful blog-posts by Amitav Ghosh: Ghosh, Amitav: On to Baghdad, issued by Amitav Ghosh, online: https://www.amitavghosh.com/docs/On%20to%20Baghdad.pdf (retrieved: 24 March 2020).

- ↑ Devi, Mokkhada: Kalyan-Pradeep. The Life of Captain Kalyan Kumar Mukhopadhyay, I. M. S., Calcutta 1928. See Das, India, Empire, and First World War Culture 2018, pp. 239-255.

- ↑ See Mitra, Priti Kumar: The Dissent of Nazrul Islam. Poetry and History, Delhi 2009, pp. 29-33.

- ↑ Translated by Diya Gupta. Also see Islam, Rafiqul (ed.): Kazi Nazrul Islam. A New Anthology, Dhaka 1990), p. 26.

- ↑ Jat Gazette, November 1914. Translated from Punjabi by Arshdeep Singh Brar.

- ↑ Fazl-i-Hussain, Muhammed: Bahar-i-Jarman [The Spring of the Germans], Moradabad 1915. Translated from Urdu by Asad Ali Chaudhury.

- ↑ Ghadar di Gunj [Echoes of Mutiny], San Francisco 1916, p. 16.

- ↑ Azad, Bishan Sahai / Dattatreya, Piyare Mohan: Fasana-i Jang-i Yurap [The Story of the War in Europe], Lahore 1914. Translated by Asad Ali Chowdhury.

- ↑ Quoted in Chandan, Amarjit: How They Suffered. World War I and Its Impact on Punjabis, issued by Academy of the Punjab in North America, online: http://apnaorg.com/articles/amarjit/wwi/ (retrieved: 24 March 2020), where many of the songs are quoted and translated. Also see Chandan, Amarjit: Punjabi Poetry on War, issued by The Sikh Foundation International, online: http://www.sikhfoundation.org/article-Amarjit_Chandan.html (retrieved: 24 March 2020).

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Naidu, Sarojini: The Broken Wing. Songs of Love, Death and Destiny 1915-1916, London 1917, pp. 5-6.

- ↑ Das, India, Empire, and First World War Culture 2018, pp. 68-72.

- ↑ Devi, Swarnakumari: Four Short Stories, Madras 1918, pp. 226-239. The story is extracted in Higonnet, Lines of Fire 1999, p. 383.

- ↑ Guleri, Chandradhar Sharma: At Her Bidding, in: Indian Literature 102/27/4 (1984), p. 41. Translated from Hindi by Jai Ratan.

- ↑ Das, Sisir Kumar (ed.): English Writings of Rabindranath Tagore. Poems, New Delhi 1994, p. 190.

- ↑ Tagore, Rabindranath: Nationalism, London 2010, p. 62.

- ↑ See Majeed, Javed: Muhammed Iqbal. Islam, Aesthetics and Postcolonialism, London 2009.

- ↑ Quoted in Chung, Tan et al. (eds.): Tagore and China, Delhi 2011, p. 79.

- ↑ Iqbal, Muhammed: Payam-i-Mashriq [A Message from the East], Lahore 1922, p. 91.

- ↑ Anand, Mulk Raj: Across the Black Waters, Delhi 1939, p. 7. See Das, India, Empire, and First World War Culture 2018, pp. 343-366.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 93-94.

Selected Bibliography

- Anand, Mulk Raj: Across the black waters, Jonathan Cape 1940: London.

- Buck, Claire: Conceiving strangeness in British First World War writing, London 2015: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Das, Santanu: India, empire, and First World War culture. Writings, images, and songs, Cambridge 2018: Cambridge University Press.

- Das, Santanu (ed.): The Cambridge companion to the poetry of the First World War, Cambridge 2013: Cambridge University Press.

- Devi, Mokkhada: Kalyan-Pradeep. The life of Captain Kalyan Kumar Mukhopadhyay, I. M. S., Calcutta 1928: Satish Chandra Mukhopadhyay and Rashik Law Press.

- Devi, Swarnakumari: Mutiny: Four short stories, Madras 1918: The Cambridge Press.

- Grimshaw, Roly, Wakefield, J. / Weippert, J. M. (eds.): Indian cavalry officer, 1914-15, Tunbridge Wells 1986: Costello.

- Guleri, Chandradhar Sharma: At her bidding, in: Indian Literature 27/4, 1984, pp. 39-54.

- Higonnet, Margaret R. (ed.): Lines of fire. Women writers of World War I, New York 1999: Plume.

- Iqbal, Muhammad: Call of the marching bell. English translation and commentary of Bāng-i-Darā, St. John's 1997: M. A. K. Khalil.

- Iqbal, Muhammad: A message from the East. A translation of Iqbal's Payam-i Mashriq into English verse, Lahore 1977: Iqbal Academy Pakistan.

- Islam, Kazi Nazrul, Islam, Rafiqul (ed.): Kazi Nazrul Islam. A new anthology, Dhaka 1990: Bangla Academy.

- Kant, Vedica: 'If I die here, who will remember me?' India and the First World War, New Delhi 2014: Lustre Press/Roli Books.

- Kipling, Rudyard: The eyes of Asia, Doubleday, Page & Company 1918: New York.

- Roy, Franziska / Liebau, Heike / Ahuja, Ravi (eds.): 'When the war began we heard of several kings'. South Asian prisoners in World War I Germany, New Delhi 2011: Social Science Press.

- Sarbadhikari, Sisir Prasad: Abhi Le Baghdad (On to Baghdad), Calcutta 1957: Privately printed.

- Singh, Gajendra: The testimonies of Indian soldiers and the two world wars. Between self and Sepoy, London 2014: Bloomsbury.

- Singh, Nand: Vada Jung Europe (The great European war), Ludhiana 1934: Kavishar Gurdit Singh.

- Tagore, Rabindranath: Nationalism, London 2010: Penguin Books.

- Tagore, Rabindranath, Das, Sisir Kumar (ed.): The English writings of Rabindranath Tagore, volume 1, New Delhi 1994: Sahitya Akademi.