Background and Recruitment↑

France had a long tradition of recruiting soldiers in West Africa, beginning with indigenous men recruited by the trading companies that first began to exploit the area in the 17th century. In 1857, the military governor of Senegal, Louis Faidherbe (1818-1889), formed the first permanent battalion of tirailleurs sénégalais, who were to become an integral feature of the colonial army.[1] These units would undergo a steady expansion throughout the rest of the century, and though recruitment came to encompass virtually the whole of the 1.8 million-square-mile federation of French West Africa, the designation of these troops as “Senegalese” testified to their original origins in the coastal areas first under French control.

Early recruitment depended heavily upon the slave trade. French military authorities paid an enlistment bonus directly to a slave’s master, and the “freed” slave then owed twelve to fourteen years of service to the army. By forming permanent indigenous units and professionalizing the force in the 1850s, Faidherbe hoped to attract young men of higher social status. By the end of the 19th century, this combination of compulsion and volunteerism had produced two regiments of tirailleurs used for conquest and security in West Africa and in other colonies.[2] In 1910, the publication La force noire by Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Mangin (1866-1925) spurred the expansion of recruitment in West Africa and the first steps toward formal conscription. The region was, he argued, an “inexhaustible reservoir of men” that could provide 10,000 volunteers per year, if not many more, to guarantee French security not only in the colonial empire, but in Europe in the event of war.[3] Though the massive recruitment that Mangin and others advocated did not fully emerge before 1914, both the intellectual justification and formal administrative mechanisms were in place to open the way for large numbers of West Africans to contribute to the French war effort during the Great War.

In addition to the 31,000 tirailleurs sénégalais already in the French army upon the outbreak of war, France recruited 161,000 more men by the end of 1918. Several thousand West Africans from the Four Communes, known as originaires, served not as tirailleurs in the colonial army, but as soldiers integrated into the metropolitan army because their residency in these privileged areas conferred upon them the rights and duties of French citizenship.[4] Throughout the war, recruitment relied on a blend of volunteerism and formal conscription, though it is important to keep in mind that even so-called “volunteers” were often subject to some form of coercion. French military and colonial officials would often, for example, give local village notables or “chiefs” quotas of men to provide for the army. These indigenous authorities would, in their turn, sometimes put forward younger sons, or weak, sick, poor, or otherwise marginal members of the community to satisfy French demands. Add to this the more generalized unequal power relations, limited opportunities, and often poverty created by colonial rule itself, and it becomes very difficult to sort out genuine volunteerism from coercion.

The numbers of West Africans incorporated into the French army waxed and waned over the course of the war. 1914 (10,000) and 1915 (22,000) saw gradual increases, while 1916, the crisis year of Verdun, witnessed an unprecedented influx of 59,000 men. In reaction to the resulting social and economic strains and indigenous resistance, the colonial administration slowed the pace of recruitment in 1917, but a spectacular renewal of efforts in 1918 produced 63,000 new recruits. Georges Clemenceau (1841-1929), who had taken over power as both prime minister and minister of war, spurred this new effort by sending Blaise Diagne (1872-1934) to lead the recruitment effort. Diagne’s energy and status as a black African and member of the French parliament representing the citizens of Senegal’s Four Communes propelled this massive recruitment drive at the very end of the war.[5]

Deployment and Experiences during Wartime↑

134,000 tirailleurs sénégalais served on the Western Front during the war. Some of these same men, plus others of the 192,000 in the army during these years, also served in the Dardanelles campaign of 1915 and in the Balkans from 1915 to 1918. West African units continued to serve in various areas of the French colonial empire during this time as well, especially in Morocco and Algeria.

Sent to the front in France from the first weeks of the war, the tirailleurs saw a great deal of combat. This was largely because French army commanders viewed West Africans as an elite fighting force among the 500,000 colonial subjects (from Algeria, Tunisia, Morocco, Madagascar, and Indochina) who fought for France during the war, and so deployed tirailleurs sénégalais most often as attacking “shock troops.” Conventional wisdom in the army held that West Africans’ alleged primitive savagery made them ideal for the offensive and rapid frontal assaults, but their less-developed nervous systems and childlike simplicity rendered them fearful and undependable under sustained bombardment and in static activities such as holding frontline trenches. In short, French officers regarded West Africans in general as a “martial race,” or race guerrière, and this racialized vision of inherent military aptitude structured West Africans’ experiences from recruitment to deployment, and beyond.[6]

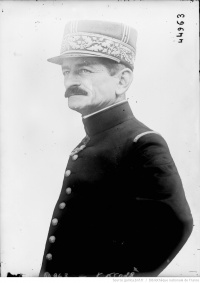

One concrete consequence of these attitudes was that West African troops under the command of General Charles Mangin played a prominent role in French plans for a massive, and many hoped war-ending, offensive in spring 1917. This Nivelle Offensive was a disaster in many - perhaps all - ways, but units of tirailleurs suffered notoriously in the cold, wet trenches on the Chemin des Dames as the offensive was delayed, then marched uphill into the withering fire of deeply entrenched German forces and suffered correspondingly devastating casualties. A more general consequence of West Africans’ reputation as shock troops during the war as a whole was a relatively high casualty rate. Scholars disagree about whether the army deployed West Africans as “cannon fodder.” While it is true that by some measures West African mortality rates are roughly equal to those of white French troops, it is apparent that tirailleurs suffered higher rates when one considers proportions of combatant troops rather than all troops in uniform. Moreover, casualty rates for West Africans increased as the war went on, while overall French rates decreased, and rates for particular groups among the West Africans considered particularly “warlike,” and so more often used in offensives, were notably and disproportionately high.[7]

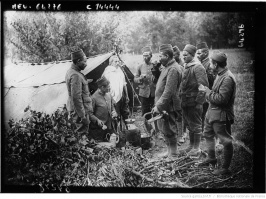

Aside from casualties, the terrors of combat, and the routine of life as a soldier, West Africans underwent the unprecedented experience of encountering French and European culture in Europe itself. Since their tropical origins caused them to suffer particularly acutely from winter weather on the Western Front, tirailleurs spent the season encamped either in North Africa or, more commonly, in the south of France. This practice of hivernage (“wintering”), as well as other periods away from the trenches and among French civilians and the general experience of serving among many white French fellow soldiers, produced a great deal of intercultural and interracial contact. This ranged from encounters with the French language, to commercial and interpersonal interactions, to romance and sex across the color line.[8] Amicable relations and friendships developed, but discrimination and racism, even violence, were not infrequent as well.

Aftermath and Effects of the War↑

Approximately 30,000 tirailleurs sénégalais died during the First World War, and many tens of thousands more were wounded. Aside from this loss of lives and damage to bodies, many families were left grieving and without the presence and support of these loved ones, as was of course the case throughout the world after 1918. Though losses among the tirailleurs, at 0.28 percent of the population, did not constitute the same demographic trauma that affected some other combatant nations (France, for instance, lost some 3 percent of its total population), recruitment and economic mobilization had exhausted and even damaged much of the region, and had important social effects throughout French West Africa.

Perhaps the most famous, or infamous, legacy of the tirailleurs sénégalais was the so-called Black Shame (in German, Schwarze Schmach) in the immediate aftermath of the war. Some West African soldiers were among the troops sent to occupy the German Rhineland after the Armistice. Many Germans regarded this as a deliberate racial humiliation heaped upon the ignominy of having lost the war, and soon lurid (and spurious) stories of the rape of white German women by black French soldiers began to circulate. This caused a huge international scandal, and continued long after France withdrew its West African soldiers from among the occupying forces.[9] Adolf Hitler’s (1889-1945) German forces took their revenge in 1940 not only by blowing up a prominent statue honoring the tirailleurs sénégalais in Reims when they occupied the city, but by routinely massacring West African troops trying once again to defend France from invasion.[10]

In French memory, the tirailleurs sénégalais have long held a special, if ambiguous place among troops from the colonies who fought in the Great War. In 1915, the image of a smiling West African soldier first appeared on advertisements and boxes of the popular French breakfast drink Banania, and the company continued to use this image and capitalize on these troops’ popularity for almost a century. The image and the slogan, “Y’a bon!,” from the fractured, pidgin French so closely associated with these men, remains one of the most instantly recognizable icons in French advertising history. But this testifies not just to the popularity of the tirailleurs, but to the haze of racialized and racist stereotypes through which many in France have viewed these men.

In West Africa, memories of the tirailleurs in the Great War have also remained ambiguous, befitting the ambiguous legacies of colonialism and decolonization. As soldiers for the former colonial power, West Africans who served the French played a complex role in African societies as they became independent.[11] This can, for instance, take concrete form in Senegal today. In Dakar, the capital, one can find a vintage tin of Banania featuring the smiling tirailleur displayed in a recreated trench in the Musée des Forces armées du Sénégal, a museum dedicated to telling the stories of armed resistance to French conquest, service to France in its army, and the history of the army of Senegal after independence in 1960.[12] Even more ambiguous and changing has been the history of a famous statue dedicated to the tirailleurs. Inaugurated in 1923 in a prominent location in the heart of the city, in the center of a busy traffic circle, the statue features a tirailleur (“Demba”) arm-in-arm with a French comrade (“Dupont”), on a pedestal featuring the effigies of French military and political figures prominent in the conquest and rule of French West Africa. This symbol of colonial and martial fraternity eventually became unwelcome in the newly independent Senegal, so in 1983 the government had it moved to an obscure location in a cemetery. In 2004, Senegalese President Abdoulaye Wade re-inaugurated the statue on the occasion of the “Journée du Tirailleur” in the center of Dakar, opposite the train station in an area now known as the “Place du Tirailleur.” A nearby inscription reads, “To our dead, honor and eternal recognition of the Nation.” Whether the nation in question is the France that asked its colonial subjects to defend the Republic without enjoying the rights of citizens, or the independent Senegal that did not yet exist when these men fought in the Great War, is a question left open for the reader to decide.

Richard S. Fogarty, University at Albany, State University of New York

Section Editor: Michelle Moyd

Notes

- ↑ Balesi, Charles John: From Adversaries to Comrades in Arms: West Africans and the French Military, 1885-1918, Waltham 1979, pp. 3-6.

- ↑ Echenberg, Myron: Colonial Conscripts: The Tirailleurs Sénégalais in French West Africa, 1857-1960, Portsmouth 1991, pp. 8-11.

- ↑ Mangin, Charles: La force noire, Paris 1910; Michel, Marc: L’Appel à l’Afrique. Contributions et réactions à l’effort de guerre en AOF, 1914-1919, Paris 1982, pp. 2-12.

- ↑ Michel, L’appel à l’Afrique, p. 404. African residents of the Quatre communes de plein exercise, the four municipalities of Saint-Louis, Dakar, Gorée and Rufisque in Senegal, were known as originaires and enjoyed special electoral rights that allowed them representation in French parliament, rights they had won for their loyalty to the Republic during the Revolution of 1848.

- ↑ Fogarty, Richard S.: Race and War in France. Colonial Subjects in the French Army, 1914-1918, Baltimore 2008, pp. 15-54.

- ↑ On French ideas about “martial races“ as they applied to West Africa, see Lunn, Joe: Memoirs of the Maelstrom. A Senegalese Oral History of the First World War, Portsmouth 1999, and Fogarty, Race and War in France.

- ↑ Michel, L’appel à l’Afrique, pp. 405-408; Lunn, Memoirs of the Maelstrom, pp. 140-147.

- ↑ For love and sex across the color line in France during the war, see Fogarty, Race and War in France, pp. 202-229, and Stovall, Tyler: “Love, Labor, and Race. Colonial Men and White Women in France during the Great War,” in: Stovall, Tyler/Van den Abeele, Georges (eds.): French Civilization and Its Discontents. Nationalism, Colonialism, Race, Lanham 2003, pp. 297-321.

- ↑ Van Galen Last, Dick: Black Shame. African Soldiers in Europe, 1914-1922, London 2015.

- ↑ Scheck, Rafael: Hitler’s African Victims. The German Army Massacres of Black French Troops in 1940, Cambridge 2006.

- ↑ Mann, Gregory: Native Sons. West African Veterans and France in the Twentieth Century, Durham 2006.

- ↑ The tin of Banania was present during a visit on 22 October 2015.

Selected Bibliography

- Balesi, Charles John: From adversaries to comrades-in-arms. West Africans and the French military, 1885-1918, Waltham 1979: Crossroads Press.

- Echenberg, Myron J.: Colonial conscripts. The Tirailleurs Sénégalais in French West Africa, 1857-1960, Portsmouth; London 1991: Heinemann; J. Currey.

- Fogarty, Richard: Race and war in France. Colonial subjects in the French army, 1914-1918, Baltimore 2008: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Lunn, Joe Harris: Memoirs of the maelstrom. A Senegalese oral history of the First World War, Portsmouth; Oxford; Cape Town 1999: Heinemann; J. Currey; D. Philip.

- Michel, Marc: L'appel à l'Afrique. Contributions et réactions à l'effort de guerre en A.O.F. (1914-1919), Paris 1982: Publications de la Sorbonne.