Introduction↑

The changes to the structure, operation and meaning of the prisoner of war camp that occurred after 1914, particularly in western Europe encapsulated the important major societal transitions that the war brought, in particular with regard to technology, governance and gender identity.[1] New technologies, ranging from mass vaccination, rail networks and floodlighting, to better preserved foodstuffs, enabled the modern mass prison camp to develop. As the war went on, state intervention became the norm as governments were increasingly forced to intervene in prisoner affairs to ensure the most efficient allocation of prisoner labour in the home front war economy and to enforce basic standards in military-run prisoner camps. Gender norms were challenged by all-male camp environments where men could no longer easily define their masculinity through the alterity of the female presence, lacking daily contact with women.[2] In the camp, male prisoners carried out the roles of caring and domestic work. Although this was also the case at the front, men at the front were only in the trenches for short periods, encountering women behind the lines; in contrast, male prisoners had very little chance to speak with women. Moreover, the fact of being captured was, for many men, a humiliating experience which also often damaged or changed a soldier’s sense of masculine identity.

Despite their importance, however, only recently have First World War prisoners of war become the subject of historical study, with the first scholarly histories appearing since the 1990s, by Annette Becker, Uta Hinz, Richard Speed, Reinhard Nachtigal, Alon Rachamimov, Oksana Nagornaja, Giovanna Procacci and Heather Jones among others.[3] The reasons why prisoners remained overlooked for so long are complex – however, it was partly because after 1918 the focus was very much upon the battlefield war dead rather than the war’s prisoners, and partly because the horrific treatment of prisoners of war in the Second World War, in German, Japanese and Soviet captivities in particular, overshadowed the history of captivity in 1914-1918. The fact that most of the First World War’s estimated 8 to 9 million prisoners were taken on the Eastern Front, by Wilhelmine Germany, Austria-Hungary and Tsarist Russia, empires that did not survive the war, was another reason why captivity was forgotten.[4] The new Bolshevik Russian regime had little interest in commemorating those it considered had been captured fighting an imperialist war on behalf of a predecessor state it disrespected; the Austro-Hungarian national successor states likewise had little incentive to remember the 2.1 million Austro-Hungarian troops captured by Russia. In total, Austria-Hungary and Germany between them captured approximately half of the war’s total prisoners. Germany already held over a million prisoners by 1915, mostly Russians captured at Tannenberg and Masurian Lakes in 1914, but also thousands of British troops taken during the British Expeditionary Force retreats of August and September 1914, as well as French prisoners taken during the initial weeks of mobile warfare in the west before the trench stalemate set in, including tens of thousands of French troops captured after the fall of Maubeuge fortress.

Capture↑

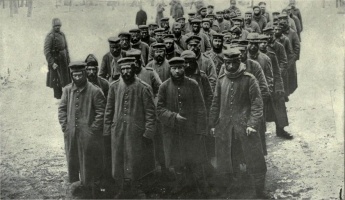

As the above illustrates, mobile warfare led to higher numbers of men captured than trench fighting. This rule generally held true for the whole of the war. The Eastern Front, with its rapidly moving offensives and retreats, facilitated prisoner-taking on a vast scale; more than half of total Russian casualties were accounted for by men who were taken prisoner.[5] One-third of the total number of men mobilized by Austria-Hungary, “about 11 per cent of the total male population of the Dual Monarchy,” was taken prisoner.[6] When the Italian front collapsed at Caporetto in 1917 an estimated 250,000 Italians were taken prisoner. The war also gave rise to famous capture moments when large numbers of prisoners were taken after armies were surrounded and cut-off. The Mesopotamian Front resulted in a high prisoner tally when a British imperial force, made up largely of troops from the Indian sub-continent, was cut-off and surrounded by the Ottoman army at Kut-al-Amara and ultimately surrendered, resulting in the Ottomans capturing over 10,000 men. High tallies of prisoners captured after besieged sites fell also occurred on the Eastern Front, for example, in 1915, with the fall of Przemyśl fortress to the Russians when over 126,000 were captured.

In contrast, Britain and France, with their main war effort on the virtually static Western Front, took far fewer captives than Germany, Russia or Austria-Hungary, until 1918 when, with the failure of the Ludendorff Offensive, Germany’s army broke and Allied prisoner-taking soared; approximately 340,000 Germans surrendered between 18 July 1918 and the Armistice, thereby playing a major role in weakening the German army and bringing about the Allied victory.[7] The extent to which German soldiers were captured as a result of Allied military prowess in July – November 1918 or surrendered en masse as a result of war-weariness without fighting, remains the subject of ongoing historical debate: the latest research by Alexander Watson suggests that most German units surrendered in an orderly fashion, with the full participation of their junior officers who supervised and negotiated the capitulation of the men in their command.[8] Yet aside from this debate surrounding German surrenders on the Western Front in 1918, little historical investigation has taken place into the motivations for combatant capitulation in the Great War. Indeed, more generally, the circumstances in which a man was taken prisoner were a highly sensitive issue, a subject that aroused shame, humiliation and suspicion during the conflict, particularly in Italy and France, even though many men were often captured through no fault of their own, due to being wounded or outnumbered by the enemy. As a result, historians face considerable challenges in obtaining source material that accurately reflects a man’s true experience of the moment of capture.

As Watson’s work suggests, however, during the Great War there were accepted procedures by which men could be taken prisoner on the battlefield. These were generally based upon transnational military customs which were well-established by the outbreak of the war – all belligerent armies claimed that they granted quarter – but by 1914 they were also enshrined in both domestic military and international law. In particular, international law set out key protections for prisoners: the 1864 Geneva Convention stipulated that wounded men who fell into enemy hands should be provided with medical care; the 1899 and 1907 Hague Conventions set out that prisoners of war should be treated humanely and outlined a range of regulations, intended to standardise prisoner treatment and protect captives from abuses. Yet what actually happened at the moment of surrender – the extent to which surrender was accepted or how often men surrendering were shot out of hand – remains one of the least researched, or indeed researchable, aspects of the Great War.[9] On all of the war’s fronts, there were many cases of quarter being refused to surrendering soldiers; this has been little studied and what research has been done relates to the Western Front where prisoner-killing at capture appears to have occurred on all sides, immortalised in Siegfried Sassoon’s (1886-1967) poem Atrocities, in which he related how a British soldier told him how he “butchered prisoners.”[10] However, the scale of such prisoner-killing on the battlefield is difficult to assess and historians disagree as to the extent to which it occurred.[11] Alan Kramer has suggested that prisoner killing “was the exception to the general rule,” whereby surrender was accepted in 1914-1918.[12] It is clear from the numbers of prisoners taken on certain fronts – for example, the low number of Ottoman prisoners taken by the Russian army or the extremely low numbers of British, Australian and New Zealand prisoners of war (just over 400) taken by the Ottoman army on the Gallipoli front – that on some fronts capture was rare, probably due to a combination of both environmental and cultural factors.[13] The number of American prisoners in Germany was also low (just over 2,400), due to the late entry of the US into the conflict.[14] For similar reasons, few German prisoners taken by America had reached the United States before hostilities ended. Additionally, other states, such as Belgium, Canada and Australia, held few combatant prisoners, often because they transferred captives to their allies.

On many fronts, however, it was not too few, but rather too many, prisoners being taken that posed problems for belligerent states. In particular, Germany, Russia and Austria-Hungary had not adequately planned for housing, feeding and clothing large numbers of captives and were overwhelmed in 1914 by the scale of their captures. The general expectation of a short war exacerbated this problem – little thought had been given to housing prisoners of war during the winter. Although all states tried to privilege officer prisoners in the first years of the war, placing them in separate prisoner of war camps from the other rank prisoners and providing them with better living conditions (in keeping with the norm across all the belligerent cultures and the stipulations in international law), other rank prisoners faced a far more difficult time. Officer prisoners were paid a salary on behalf of their home state by the captor state and assigned orderlies from the captives of their own army to carry out the menial tasks of day-to-day living, including making beds and laundry; they were also exempt from being put to work thanks to an amendment added to the 1907 Hague Convention. Other rank captives, in contrast, were usually forced to work, for a derisory payment, of which only a token amount was ever given to them in worthless “camp coupons” rather than real currency, and had little say over the tasks involved. However, in a reference back to their pre-war freedoms, it was not uncommon for prisoner workers to attempt a strike if they felt their working conditions – in particular their working hours – were unacceptable.[15] Across all belligerent states, class proved the most important common determinant as to a prisoner’s individual overall chances of surviving captivity; while some officers experienced harsh conditions, the general pattern was that they were far better protected than other rank captives.

Constructing the Camp System↑

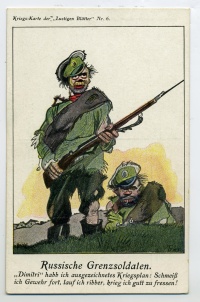

In much of Germany prisoner transport was relatively chaotic in the first months of the war with captives transported by rail in waggons that had previously been used to deliver horses to the front. For wounded prisoners these unsanitary transport conditions raised the threat of infection. Upon arrival in Germany, many prisoners of war were faced with very poor conditions in the first weeks of the conflict: for some prisoners, accommodation was improvised in tents, military barracks or old fortresses. However, large numbers of prisoners were accommodated in fields without shelter while those who were fit were put to work building the infrastructure of the prisoner of war camp which was to accommodate them before winter set in. Guards were frequently violent in camps for other rank prisoners. Prisoner of war camps were under the control of regional military commanders who reported directly to Wilhelm II, German Emperor (1859-1941) and who initially had considerable freedom in managing the prisoners of war sent to their region; this led to great variation of standards in the early stages within camps in different German regions as well as to harsh discipline by guards where local commanders did not intervene. In some camps in Germany during this first phase of the war combatant prisoners of war were held in one section and civilian deportees from France and Belgium in another. Overall, the trend across Europe was to segregate combatant prisoners of war from both civilian internees and from the local home front population as much as possible. Local home front civilians were often curious about captives, however, and the first weeks of the war saw civilian crowds gathering to view prisoners being transported and to view the first prisoner of war camps, a phenomenon that was widespread, particularly in Britain, France and Germany. In the German case, during this early phase of the camp system, the historian Oxsana Nagornaja has argued that the population viewed Russian prisoners through stereotyped images of Slavs as inferior. This view was influenced by “colonialist” attitudes, built up from mass market fiction and wartime propaganda.[16] Discipline in German home front camps during the period 1914-1915 was harsher than in their British and French counterparts with captives of all nationalities often subjected to the punishment of Anbinden – being tied to an upright post for long periods. Beatings were also common; accounts of punishments inflicted in the camps noted that the Russians are “accustomed to iron coercion in their homeland.”[17] In the case of Russia, prisoner organisation was similarly chaotic in the first year of the war; it took two years to build the large scale prisoner of war camps the country required and many prisoners were quickly sent to live and work outside a camp.[18]

Partly as a result of the improvised conditions for prisoners during the first six months of the war, typhus epidemics broke out in German and Russian prisoner of war camps in 1915. The most notorious epidemic in Russia was at Totskoe camp where “at least 10,000 men died out of 25,000.”[19] In Germany there were major outbreaks at over thirty camps, with the epidemics at Wittenberg and Gardelegen camps being used in Allied propaganda as evidence of poor German prisoner of war treatment. Both Germany and Russia responded to this epidemic by introducing better hygiene regulations in their prisoner of war camps. In Germany disinfection measures were put in place by late 1915 to disinfect prisoners’ clothes and bodies to remove all lice. The risk of typhus forced armies to immediately quarantine newly captured prisoners and to instigate sophisticated disinfection of captives near the front – the prisoner thereby became associated with the danger of contamination, which had to be controlled. The British routinely deloused German prisoners as soon as possible after their capture, and those found to be suffering from typhus were segregated in a special establishment near Tournai that was run by a monastic order.[20] This fear of disease also influenced British treatment of Ottoman prisoners captured on the Mesopotamian front: after disinfection all Ottoman prisoners of war were provided with new clothing upon arrival at the main POW camp at Ma'gril near Basra.[21]

The 1915 typhus epidemic was the only major prisoner of war epidemic to occur in First World War prisoner of war camps as a result of poor conditions, testimony to the better hygiene and sanitation knowledge that developed. In 1918, the Spanish influenza epidemic occurred among prisoners of war but it stemmed from a virus whose causes lay outside the prisoner of war camps and also affected the civilian population equally severely. The main medical issue concerning prisoners of war during the conflict was how to deal with prisoners recovering from battlefield wounds; in this regard, belligerents largely respected the 1864 and 1906 Geneva Conventions, treating prisoners of war in front line casualty clearing stations and home front hospitals and providing medical care in prisoner of war camps. The main problem in this regard was that medical supplies were often very limited, particularly in Germany and Russia, with Germany suffering from a shortage of cotton needed for dressings.

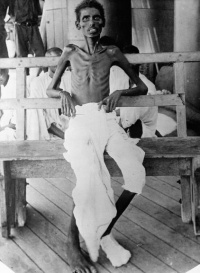

As the war went on, feeding prisoners of war proved increasingly difficult for the Central Powers. Germany and Austria-Hungary, facing naval economic blockades, were faced with feeding prisoners of war in the context of increasing food shortages. This led to the German decision in 1915 to feed prisoners the same ration quantities as German civilians were allocated, a breach of the Hague Conventions which stated that prisoners must be fed the same food as the captor army’s own troops. However, not only Germany but also Austria-Hungary and Russia faced difficulties in supplying adequate food to prisoners; in the Russian case it was decided that sending state food parcels to Russian prisoners in Germany would only assist the enemy materially, and so Russian prisoners were forced to live on meagre and inadequate German prisoner of war camp rations.[22] For prisoner nationalities who received food parcels sent from their home state, their families or their national Red Cross or other charities, the impact of food shortages was relatively limited. Likewise for those prisoners of war working in agriculture – over 735,000 prisoners in Germany by 1916 and almost 500,000 in the Austro-Hungarian Empire by 1918 – the impact of food shortages was offset by additional food often provided by farmer employers who tended to treat prisoner of war labourers the same way they would treat a peacetime hired hand.[23] In Russia, during the summer months when the most labour intensive agricultural work took place, rank and file prisoner of war camps would be “almost completely empty (except for NCOs and invalids who could obtain exemptions) and the prisoners were sent in small or medium-sized groups to estates and peasants’ farms.”[24]

Prisoner Labour↑

By 1916, the principal European belligerent states had all established prisoner of war camps, secure locations segregated from the civilian population, where prisoners were confined using barbed wire, sentry towers and guards and accommodated usually in wooden barracks. Some countries continued to use older fortresses as well. These prisoner of war camps had by 1916 largely become spaces of transition – where prisoners made the transformation from battlefield soldier to forced labourer on the home front. The majority of other rank captives were working outside their prisoner of war camp by 1916. In Germany, 90 percent of prisoners or 1,449,000 out of 1,625,000 were working.[25] Britain was the belligerent state that was slowest to employ its prisoners of war on the home front, largely because of trade union opposition to the use of prisoner labour, as the unions feared it would undercut civilian wages. It was only in 1918 that Britain had a fully developed prisoner of war labour system, using prisoners mainly in forestry and quarrying work. By the middle of the war, most belligerent states were no longer respecting the Hague Convention stipulation that prisoner labourers not be put to work on tasks directly connected to the war effort. In a total war, with whole economies geared towards military production, this stipulation was rapidly abandoned.

Some home front labour by prisoners was extremely harsh resulting in high death rates. Of the 70,000 Austro-Hungarian and German prisoners used by Russia to construct the Murmansk railway, 25,000 died, mostly Austro-Hungarians. Death rates were also very high for Italian prisoners captured by the Central Powers; of the 468,000 held by Austria-Hungary at least 92,451 died, a death rate that Alan Kramer has calculated at 19.75 percent.[26] In contrast, of the 477,024 Austro-Hungarian combatant prisoners held by Italy, 18,049 died, suggesting they were generally relatively well-treated; among Italy’s Austro-Hungarian prisoners was the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951), held at Cassino.[27] However, it was Romanian prisoners in Germany who suffered among the worst death rates of the war with 29 percent not surviving captivity. Prisoners died from a range of causes in the First World War: old battle wounds, malnutrition, tuberculosis, typhus, beatings, overwork and the influenza epidemic at the end of the war being the most prominent culprits.

Prisoners were also used directly as labour by the armies fighting the war. This varied from the improvised use of newly captured prisoners to help carry the wounded from the battlefield to the much more sophisticated employment of prisoner of war labour companies, permanent units made up of captives that remained at or near the battlefronts to do heavy manual work such as loading and unloading shells, road building and maintenance and on occasion, trench construction work. The German army established prisoner of war labour companies on the Western Front in 1915, made up of Russian prisoners, and later, of British, French, Italian and Romanian prisoners. The British and French armies established prisoner of war labour companies in 1916; indeed by July of that year 50 percent of all German prisoners held by France were working for the French army either in prisoner of war labour companies in the war zone or for the army on the home front.[28] The German army additionally used prisoner labour in the East.[29] The Austro-Hungarian and Russian armies also used prisoner of war labour companies. The development of prisoner labour companies marked a shift during the First World War towards the increasing and more ruthless exploitation of captive labour. Living conditions in prisoner of war labour companies were often harsh and in the Austro-Hungarian case, in particular, death rates were high. For those prisoners working for the German army in 1918, beatings and malnutrition were common, despite frequent orders from the third German Oberste Heersleitung (OHL) asking that prisoner labour strength be carefully conserved as it was desperately needed.

Humanitarianism↑

The First World War saw an ongoing struggle by those activists who sought to humanise captivity, to uphold existing international law and to deliver material aid to prisoners who needed it. A wide range of groups were involved in this process. Neutral states took on the role of “protecting power” for particular prisoner nationalities at the outbreak of the conflict. In 1914, for example, the United States accepted responsibility to act as the protecting power for British prisoners of war in Germany and Germans in the United Kingdom; Spain took on the role of protecting power for French prisoners of war in Germany and for Ottoman prisoners of war in Russia. After the United States entered the war, Switzerland took on the role of protecting power for German prisoners in the United Kingdom. The protecting power sent its diplomats to inspect camps and also investigated complaints by prisoners of war from the belligerent nationality whose interests it represented.

Along with the protecting power system, the development of the International Red Cross was key to ensuring that prisoner treatment in the First World War remained within certain humanitarian parameters. The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) set up a Prisoner of War Agency at the start of the war which tried to locate men reported missing who had been taken prisoner. The ICRC also arranged for prisoner of war camp inspections in prison camps across Europe and around the globe; camps in locations as far flung as Burma and Algeria were inspected by ICRC officials, usually Swiss, who placed great store upon their neutral reputation. The inspection reports produced from these visits were intended to improve prisoner treatment standards as well as to undermine inaccurate propaganda rumours about how the enemy was treating its captives. Care parcels were also sent to prisoners by the ICRC prisoner of war agency and it forwarded letters to and from captives and their families. It established an immense card catalogue to assist it in its work of tracing the missing and prisoners of war. The ICRC sought particularly to uphold the pre-war international law protecting prisoners. During the war it came to emphasise prisoners as having legal rights to particular norms of good treatment under international law, as well as their entitlement to good treatment for moral reasons; the war thus saw a shift to a rights-based discourse at the ICRC regarding combatant prisoners, similar to that which occurred with regard to other groups such as refugees, moving away from pre-war assertions of forms of masculine gallantry and honour as the main cultural codes underpinning good treatment of captives.[30]

In Russia, prisoner camp inspections were carried out by female representatives of the national German and Austro-Hungarian Red Cross organisations, an unusual situation as national Red Cross groups and delegates were frequently viewed with suspicion in enemy countries; it was based on reciprocity as Russian women, with aristocratic connections inspected Central Power camps for Russian captives.[31] The Swedish Red Cross was also key in providing prisoner of war aid on the Eastern Front. One woman in particular, Elsa Brändström (1888-1948), the daughter of a Swedish ambassador to Russia, brought material aid in person to German and Austro-Hungarian prisoners in Siberia, for the Swedish Red Cross. She became known as the “Angel of Siberia” for this difficult and dangerous work. The outbreak of the Bolshevik revolution placed these women, often from aristocratic backgrounds, at risk: some were killed in the turmoil of the Russian Civil War.

During the conflict, a series of agreements were facilitated by neutral intermediary states such as Sweden which promoted better prisoner treatment. For example, the Stockholm Protocol was signed on 1 December 1915 by Austria-Hungary, Germany and Russia, and came into force in mid-1916. As the war continued, limited exchanges of seriously wounded or otherwise incapacitated prisoners were negotiated between belligerents, as well as the internment of a certain number of such prisoners in neutral Switzerland. Prisoners’ age, length of time spent in captivity and mental health became grounds for qualifying for exchange – a significant sign of the extent to which mental illness was now regarded as a serious threat to prisoner of war well-being. Late in the war, the Netherlands provided internment camps for British and German prisoners of war, following a bilateral agreement between the two states in 1917. These wartime agreements marked real humanitarian achievements, even if the numbers of captives affected were relatively small, and officers benefited disproportionately. The Netherlands also interned Belgian POWs from 1914: these were men who had escaped Belgium after the Fall of Antwerp in October 1914 and were interned in the Netherlands because of that state’s neutrality obligations.

Mistreatment↑

The war highlighted a wide range of varying popular understandings, which also changed over time, as to what constituted prisoner mistreatment: in 1914, British officer prisoners complained that they had been transported to Germany in cattle trucks or second class carriages; the British and French governments found it unacceptable in 1915 that Germany was holding their captives together with Russian prisoners rather than segregating the nationalities.[32] At the other end of the violence spectrum real horrors did occur: in 1914 the French government protested the shooting of prisoners of war during the German invasion of northern France and the killing of medical personnel and wounded soldiers after the surrender of a hospital at Goméry. France also began to gather evidence from captured German soldiers regarding breaches of quarter by the German army on the battlefield in 1914. Germany protested strongly at the use of German prisoners of war by Russia to build the Murmansk railway in terrible conditions. In March 1918, a British Parliamentary Paper claimed that a British prisoner Able Seaman John Genower had burned to death in the Brandenburg prisoner of war camp in 1917 when the camp prison went on fire and guards prevented the evacuation of the prison cells.[33] States also accused the enemy of refusal of quarter on the battlefield as discussed earlier.

Some mistreatment incidents were considered grave enough to trigger reprisals. In 1916, in retaliation for the French use of German prisoner of war labour in North Africa, Germany sent French prisoners of war from home front camps to work in terrible conditions in its occupied Baltic areas; when in the same year Britain commenced using German prisoner labour to unload and load cargo at French ports, Germany retaliated by sending British prisoners from Döberitz camp to work in sub-zero conditions behind the lines on the Eastern Front. While France relented relatively quickly and removed German prisoners from North Africa, thereby ensuring its men were withdrawn from the Eastern reprisals, Britain continued to use German prisoners as labour in French ports, meaning that its men remained in the East in winter 1917.

In general the war saw a radicalization of the use of prisoner reprisals to force better treatment of captives by the enemy. Perhaps the worst reprisal sequence was the decision by the third German OHL in spring 1917 to keep all newly captured, unwounded British and French prisoners of war behind the lines, in retaliation for both the French use of German prisoner labour on the Verdun battlefield where German prisoners endured very difficult – and dangerous – working conditions and the British decision to begin using German other rank prisoners of war to work in labour companies on the Western Front for the British army in 1916. Only when the French and British agreed to remove their German prisoner labourers to a distance of thirty kilometres from the front lines for all work did the OHL call off the reprisals, which took a terrible physical toll upon those prisoners subjected to them.

Public opinion often pushed for the escalation of reprisals. In 1918, the British press baron Alfred Charles William Harmsworth, Lord Northcliffe (1865-1922) placed Thomas Wodehouse Legh, Lord Newton (1857-1942), head of the Prisoner of War Committee at the Foreign Office, under significant pressure to start reprisals against German prisoners in retaliation for Germany’s poor treatment of British prisoners working in German mines and labouring for the German army in occupied France and Belgium; Newton resisted. In Germany, the right wing parties in the Reichstag applauded the announcement of the 1917 spring reprisals. In rare cases, the public sought to assist enemy prisoners; one example was the Jewish community of Berlin, which provided unleavened bread to Jewish prisoners held in captivity in neighbouring camps during Passover.[34]

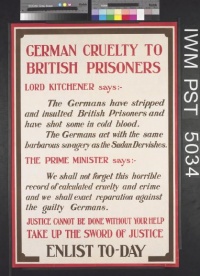

War propaganda on all sides made much of the enemy’s mistreatment of captives. Stories often painted lurid and sensationalist pictures of violence and torture, most famously in 1915 when rumours, never substantiated, spread that a Canadian prisoner of war had been crucified by the Germans on the Western Front. Yet, often war propaganda regarding prisoners of war drew upon eye-witness testimony, and the extent of distortion in newspaper and government publications reporting on real prisoner mistreatment was surprisingly limited in many cases.[35] Propaganda characterizing the enemy as barbaric made the treatment of prisoners of war into a central measure of assessment as to where a state stood on the wartime civilisation-barbarism axis.[36] For example, a key theme of the Russian Extraordinary Investigative Commission, formed in April 1915 to study violations of the laws of war by the Central Powers, was cruelty towards prisoners.[37] Belligerents therefore fiercely defended their prisoner of war treatment policies throughout the conflict.

Of course, the response to enemy mistreatment of prisoners was also related to the attitude towards men taken prisoner that existed in their home countries; in this regard, Italy was notorious for viewing Italians captured by the Central Powers, particularly after Caporetto, as cowards and traitors; the Italian state chose not to send state food parcels to its men in Central Power captivity.[38] Conditions in Austro-Hungarian camps for Italian captives were very poor, with high death rates. One exception to the general suspicion of Italians taken prisoner, however, was the author Cesare Battisti (1875-1916), an ethnic Italian from Austria-Hungary who left Austria-Hungary to fight for Italy in the war. Captured by the Austro-Hungarians in 1916 he was executed for treason; his book, Gli Alpini, published weeks after he was killed, became a bestseller. Austria-Hungary’s prisoner of war camp system was harsh for other nationalities too, particularly for Serb captives.

Prisoner treatment, however, was not only dependent on propaganda views of the enemy; it also depended on the material resources of the captor state and the extent to which state control at the local level was challenged by the exigencies of the war effort. Regions such as South East Europe, where weak state control and volatile regime change had been an issue even before the war, faced particular challenges in organising prisoner of war treatment. When Serbia was overrun by the Central Powers in late 1915 it decided to evacuate its army across the mountains of Albania; some 40,000 of their Austro-Hungarian prisoners of war marched with them, many dying on route. After reaching the coast at Valona, the 24,000 surviving prisoners ultimately were handed over to the Italians and removed to the Italian prisoner of war camp on the island of Asinara off the coast of Sardinia; 2,000 died of cholera before arriving there; many others died after their arrival, bringing the death toll on Asinara to 7,000, almost all other ranks; officer prisoners were evacuated on from the island to France.[39]

For other states in the Balkans weak governance was a major problem in developing effective prisoner of war camp networks. For Serbia’s opponent Bulgaria, which, with just over 60,000 prisoners of war, for most of the war held far more prisoners than it had lost to its enemies, prisoner of war camps were largely established on an ad hoc basis. Throughout, Bulgaria privileged its British and French prisoners over its much larger numbers of Romanian and Serb captives; it also held Russian, Italian and Greek prisoners of war.[40]

Similar to Bulgaria, the Ottoman Empire held a diverse range of nationalities among its 34,000 prisoners of war: Australians, New Zealanders, British, Indians, Romanians, Russians – including multiple ethnicities fighting in the Tsarist army – and French. The majority of the main prisoner of war camps were located in Anatolia; these often consisted of local buildings, such as schools or churches, which were turned into improvised prisoner of war camps; in some localities officer prisoners lived communally in adapted houses. Turkey, as was true of the other belligerents, held officer prisoners and other rank prisoners separately. Camps were often very remote, with prisoners isolated from news of the war and of home. Discipline and living conditions varied widely; prisoner labourers in the Taurus Mountains, including Australians working on railway building, experienced great hardship, while other captives lived in comfortable billets and some camps were able to organise theatre activities.

One of the worst captivity death rates of the conflict occurred on the Mesopotamian front when the Ottomans captured Kut-al-Amara in modern day Iraq in April 1916 after a long siege. Here the Ottoman army captured approximately 2,962 white British officers and other ranks, of whom 1,782 would go on to die in Ottoman captivity.[41] Alongside these men, the Ottoman army also captured an unknown number of Indian prisoners who, along with their white comrades, experienced a horrific death march from Kut-al-Amara to the northern railhead at Ras-el-Ain (in modern day Syria) via Baghdad; many of the captives were greatly weakened by the effects of a long siege and suffered from the impact of the harsh climate, a lack of food provision and beatings by guards during the march. In total, in the whole of the Mesopotamian campaign, some 10,686 colonial soldiers from India, including 200 Indian army officers, were captured by the Ottoman army: of these, 1,708 were reported to have died in captivity and another 1,324 were recorded as untraced at the end of the war, a very high death rate.[42] The Kut prisoners were separated at Ras-el-Ain, where white captives were entrained for Anatolia. Many Indian prisoners were kept on as forced labour. The Ottoman policy for prisoners overall was to privilege Muslim Indian captives over Hindu, Sikh and Christian ones.

Regimes of privilege also operated for captives held by Russia that sought to favour Slav captives over Germans, who were often sent to the worst camps in Siberia, far from European Russia; as early as November 1914, the Russian Stavka ordered that Slav and Alsatian prisoners receive the best food and lodgings, while Magyrs, ethnic Germans and Jews were to be treated worst. Russia also held roughly 65,000 Ottoman prisoners of war; conditions for these men varied, but some were able to attend lectures and educational classes in their camps.[43] Ottoman captives suffered badly during transport, as was the case for many captives taken by Russia who were moved in heated box cars known Teplushki across vast distances; often lack of fuel for heating meant prisoners suffered hardship or even died during transport. The Russian holding camp for Ottoman prisoners on Nargin Island, where conditions were poor, had a particularly high death rate.

The treatment of prisoners outside of Europe varied greatly. Germans captured by Japan during the siege of Tsingtao were largely well-treated, with Japan viewing good prisoner treatment as a way to assert its claim to modern world power status. The best-known German camp was Bando, where prisoners were able to put on theatre performances. The sheer global range of the prisoner of war camp network during the First World War is staggering. The British sent large numbers of Ottoman prisoners of war captured in Mesopotamia to prisoner of war camps in India. Ottoman prisoners captured fighting in Palestine were sent to camps in Egypt, where many suffered, and some died, from pellagra, due to the poor diet they were fed; other Ottoman prisoners were held in camps in Burma (Myanmar) and Cyprus.[44] German prisoners held by the French in camps in Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia in 1915 had high rates of malaria. German prisoners of war captured by the British fighting in East Africa were sent to camps as far flung as Egypt, Malta and India at Ahmednagar; in contrast, black askari troops taken prisoner were sometimes simply sent home. South Africa also held German prisoners of war taken in the fighting in German South West Africa.

Prisoner Identity↑

Encouraging prisoners to switch sides was relatively common in Europe. France tried to recruit prisoners of war from Alsace-Lorraine or ethnic Poles fighting in the German army to join the Allied cause. Germany operated a programme of indoctrination of its Muslim prisoners captured fighting with the Russian, French and British armies. Held at two camps near Zossen, Germany sought to recruit them on behalf of the Ottoman Empire. Just over a thousand of these prisoners ultimately switched sides to fight in the Ottoman army. Some of Germany’s Belgian prisoners were also subject to indoctrination at Göttingen camp in an attempt to garner support for a Flemish pro-German nationalism in Belgium. Germany operated a similar scheme towards Irish prisoners of war who were gathered at Limburg camp for the purpose of recruiting them to fight as a brigade against Britain in the planned 1916 Rising; little came of this scheme when fewer than sixty men could be convinced out of over 2,000 in the camp. Germany also offered naturalisation to ethnic Germans captured fighting in the ranks of the Russian army. Perhaps the most famous example of prisoners switching loyalties however was that of the Czech Legion, at its peak in 1918 numbering some 60,000 men. Originally recruited from among Austro-Hungarian prisoners of war to form a Legion to fight for Tsarist Russia, they became a highly effective and important fighting force. During the Russian Civil War they remained loyal to the Allied cause and took over the trans-Siberian railway until their repatriation demands were met.

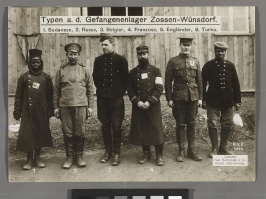

The prisoner of war camp thus became a primary locus for the shifts in identity that the war was driving more generally across Europe. Prisoners of multiple ethnicities found themselves classified by nationality and were often challenged by the attempts by captor regimes to define them. For peasant prisoner populations from the rich ethnic tapestry of Eastern and South Eastern Europe, who had often lived with minimal interaction with the state before the war, this experience of captivity among their fellow “nationals” frequently changed their identity. Prisoners of war frequently mobilised in home front camps to run educational classes and organize concerts and other cultural events that promoted a deeper sense of national understanding.[45] Likewise, home front governments and populations sought to define and categorise those now imprisoned among them. In Germany and Austria-Hungary, anthropologists – now unable to carry out field studies in remote corners of the globe due to the war – brought their subject research to the home front camp, measuring, photographing, classifying and recording captive prisoners of a wide variety of ethnic groups. Germany in particular developed a widespread discourse that at war it faced a “world of enemies,” which had encircled it. Studies and images of racially diverse prisoners of war in its camps served to reinforce this belief and so were used frequently in wartime propaganda. However, even in Britain, anthropological studies took place; in one instance measuring individuals from different German regional groups in order to understand the different internal German "races" - Prussian, Saxon and Bavarian, principal among them.

The daily life of prisoners was remarkably similar across much of western Europe, highlighting the extent to which the war was fought out of common European military cultures and based on shared societal modernization trends and technologies. Most days started with a roll call, where the prisoners were counted; the high points of prisoners’ days, as articulated in memoirs from a variety of nationalities and countries, were invariably the delivery of letters, the collection of parcels, and mealtimes. Married men with children suffered particularly from homesickness, especially during festival periods such as Christmas, which was marked in most camps by Christian prisoners. In far-flung camps in places such as Japan, Anatolia or Siberia news of loved ones by letter was irregular or non-existent. The larger home front camps usually had exercise yards or areas where prisoners could walk or play sports; some regimes allowed captives to go on escorted group walks outside the camp or provided a reading or study space. Those prisoners who worked usually had at least one day off a week, frequently Sunday; camp fatigues were done by the prisoners themselves, with wounded or weak prisoners assigned the lightest tasks. In some countries, such as Germany, prisoners of war were allowed to produce their own prison camp newspapers.[46] In general, captor states recognised the need for captives to have access to some cultural distraction or exercise in order to protect their mental health; nevertheless there were camps and working units where no such provisions existed. And even in the best run camps, some captives suffered from mental health issues as a consequence of incarceration; although suicides were rare, breakdowns, severe depression or the development of psychologically disturbed behaviours were relatively common.

Discipline within prisoner of war camps and working units was based on the military law of the captor state. Immense creativity was in evidence in the better-run camps, with prisoners performing theatre plays, organising concerts, sports tournaments, libraries and art exhibitions. Prisoners, to a greater or lesser extent, pined for the company of women, although those working in factories or agricultural tasks did sometimes strike up friendships or even relationships with local girls, even though in certain captor states such as the United Kingdom or Germany such relationships were harshly punished; in Russia, marriages between Austro-Hungarian prisoners and local women even occurred.[47] For prisoners working on the land in Europe, sexual harassment of local women was also not unknown.

In fact, even though many prisoners had become used to a temporarily single-sex environment while in the army and at the front, captivity led to concerns that prisoners would lose their virility and become passive. The effects of long-term captivity upon masculine identity were a central theme of public discourse regarding prisoners during and after the war, with captor state authorities advocating the importance of work as a way of “saving” prisoners’ manliness.[48] Some camps did see homo-erotic relationships developing; in prisoner camp theatre younger men often dressed as women and sometimes had “admirers.”[49] However, homosexual acts remained taboo.

Other prisoners sought to re-establish a sense of their soldierly identity through continuing their war against the captor state while within captivity: those working sometimes carried out acts of sabotage; others gathered intelligence that they tried to pass on to the authorities at home through coded letters or smuggled information passed back by repatriated men. For some captives, planning escape attempts provided a means of distraction and an antidote to the feelings of humiliation and shame that captivity could engender; this was particularly the case for Charles de Gaulle (1890-1970), held in Ingolstadt, who launched several failed escape attempts; Mikhail Tukhachevsky (1893-1937), later Marshal of the Soviet Union and an inveterate escape attempter, was held in Ingolstadt alongside him. Although captivity in a home front camp offered respite from the dangers of the trenches, it was not without risk for other rank prisoners: working accidents were a real problem, particularly for those involved in mining, quarrying or forestry work. Obviously prisoners working in labour companies for the front line armies endured an even more precarious captivity. These factors also provided motivation for escaping.

Among the most famous escapes of the war was the mass break-out of twenty-nine British officers from Holzminden camp using a tunnel dug with improvised tools in 1918; ten of the men reached the Netherlands and freedom. Gunther Plüschow (1886-1931), who escaped from a camp in Britain in 1915 and reached the continent, was also widely celebrated in Germany; due to Britain’s island geography it was extremely rare for a prisoner of war to regain his liberty from a British home front camp in this way. Escapes from prisoner of war labour companies on the Western Front, in contrast, were more frequent for all belligerent forces during the second half of the war.

Repatriation↑

The vast majority of the war’s captives were not repatriated before the end of the conflict – escapes, exchanges or internment in neutral Switzerland or the Netherlands remained rare fates reserved for relatively few. Upon the Armistice, the Allies demanded the release of all Allied prisoners of war in the Central Power states; German captives languished in British and French captivity until after the signature of the Treaty of Versailles. In late 1919, Britain repatriated its German captives; France, which used its German prisoners to work clearing the battlefields, dangerous tasks which saw a number of captives killed removing munitions, only repatriated its German prisoners in 1920. The retention of German prisoners in this way caused outcry in Germany and mobilised vast numbers in protest demonstrations, thereby contributing to post-war animosities.[50]

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk notwithstanding, most Russian prisoners were not released from German captivity until the war ended in 1918, although most continued to live in the camps for a period after release. Russian prisoners released by the Allies from German labour companies in occupied France and Belgium found themselves placed in French camps, pending repatriation, as France in particular did not wish to keep them. Russians in Germany were mobilized by radical left wing groups as part of the German revolution; negotiations regarding their repatriation proved a way for the new Soviet regime to send representatives to the new Weimar state.[51] In particular, Russian prisoners would play a role in supporting the left wing revolution in Munich; one consequence was that broader German public opinion came to fear Russian prisoners as dangerous Reds; Adolf Hitler (1889-1945), a prison camp guard for a period in 1919 may well have been influenced by such attitudes. A similar phenomenon was visible in Austria-Hungary during the months following Russia’s exit from the war when the first Austro-Hungarian prisoners were repatriated; many of them held Bolshevik sympathies and the state greatly feared their disruptive political influence, spreading communism.[52] These were not empty fears; the leader of Hungary’s short-lived Soviet revolution was a former Austro-Hungarian prisoner of the Russians, Béla Kun (1886-1938).

Those Russian prisoners of war in Germany, Austria and the new Hungary, who were anti-Soviet and did not wish to return to Russia after the war, in some cases found they had little choice. Some were dumped at the Russian border at the height of the Russian Civil War to make their way home on foot; they experienced great hardship, and some were shot in the civil war violence as suspected whites.

For prisoners in far-flung locations such as Japan and Siberia repatriation took even longer: 1922 saw the last of these men return to Germany and Austria-Hungary. The British retained their Ottoman prisoners in Egypt for most of 1919. Remarkably, most prisoners appear to have re-adjusted to life after captivity relatively well, despite the weakness of state aid provisions for them in many interwar belligerent states.[53] In Germany and France former prisoners arranged their own veterans’ associations to lobby for welfare rights; however, in other states prisoners avoided drawing attention to their wartime captivity and, if they joined a veterans’ association, it was often not prisoner-specific.

Yet, if at an individual level captives sought to make new lives for themselves, the legacy of captivity remained. Families had to become reacquainted with fathers long absent; men had to cope with deaths and political upheaval that had occurred in their absence, particularly in Eastern Europe and in Germany; few other rank former prisoners ever received full payment from their captor state for their wartime labour and postwar negotiations on this subject proved largely fruitless. Germany and Soviet Russia mutually waived these debts owed to each other; France received a lump sum token payment from Germany; most other states appear to have abandoned the issue, particularly successor states to the wartime multi-ethnic empires.

The ICRC set about drafting new international laws for prisoner treatment as soon as the conflict ended, which would ultimately form the basis for the 1929 Geneva Convention relative to the treatment of Prisoners of War which remains in force to this day. Punishment of war crimes against prisoners was pursued with less vigour during the 1920s. Although Article 228 of the Versailles Treaty called for the prosecution of war criminals, only a handful of German perpetrators were brought to trial at Leipzig in 1921; however, most were acquitted or received very short sentences. Ultimately, when the next global war broke out in 1939, little had been set in place in the interwar period that could halt the major escalation in war crimes against prisoners of war that ensued, particularly on the Eastern front from 1941 and by Japan in camps across its wartime Asian Empire. These horrors ultimately overshadowed the memory of First World War captivities.

Great War captivity was a chequered balance sheet of appalling negligence, forced labour and the systematization of modern incarceration systems that ensured that in western Europe at least, the majority of captives survived. It was a fundamental element of the 20th century’s first experience of total war, as important as the trenches, both in terms of the numbers affected and its legacy in terms of new attitudes to the rights of states to incarcerate and coerce those perceived as the “enemy.”

Heather Jones, London School of Economics and Political Science

Section Editors: Michael Neiberg; Sophie De Schaepdrijver

Notes

- ↑ Jones, Heather: Kriegsgefangenenlager. Der moderne Staat und die Radikalisierung der Gefangenschaft im Ersten Weltkrieg, in: Mittelweg 36. Journal of the Hamburg Institute for Social Research, 4/20 (2011), pp. 59-75.

- ↑ See: Rachamimov, Alon: The Disruptive Comforts of Drag. (Trans)Gender Performances among Prisoners of War in Russia, 1914–1920, in: American Historical Review, 111/2 (2006), pp. 362-382.

- ↑ Becker, Annette: Oubliés de la Grande Guerre. Humanitaire et culture de guerre, 1914-1918. Populations occupées, déportés civils, prisonniers de guerre, Paris 1998; Hinz, Uta: Gefangen im Großen Krieg. Kriegsgefangenschaft in Deutschland 1914-1921, Essen 2006; Speed, Richard B.: Prisoners, Diplomats and the Great War. A Study in the Diplomacy of Captivity, New York et al. 1990; Nachtigal, Reinhard: Kriegsgefangenschaft an der Ostfront, 1914 bis 1918, Frankfurt am Main 2005; Procacci, Giovanna: Soldati e Prigionieri Italiani nella Grande Guerra, con una Raccolta di Lettere Inedite, Turin 2000; Jones, Heather: Violence Against Prisoners of War, Britain, France and Germany 1914-1920, Cambridge 2011; Nagornaja, Oksana S.: Drugoj voennyj opyt. Rossijskie voennoplennye Pervoj mirovoj vojny v Germanii (1914–1922) [Eine andere Kriegserfahrung. Russländische Kriegsgefangene im Ersten Weltkrieg in Deutschland (1914–1922)], Moscow 2010; Rachamimov, Alon: POWs and the Great War. Captivity on the Eastern Front, Oxford et al. 2002.

- ↑ Oltmer, Jochen: Einführung, Funktionen und Erfahrungen von Kriegsgefangenschaft im Europa des Ersten Weltkriegs, in: Oltmer, Jochen (ed.): Kriegsgefangene im Europa des Ersten Weltkriegs, Paderborn 2005, p. 11. Other estimates put the figure between 6.6 and 8.4 million. See: Kramer, Alan: Alan: Prisoners in the First World War, in: Scheipers, Sibylle (ed.): Prisoners in War, Oxford 2010, p. 76.

- ↑ Ferguson, Niall: The Pity of War, London 1998, p. 368.

- ↑ Rachamimov, POWs and the Great War 2002, p. 4; p. 31.

- ↑ Ferguson, The Pity of War 1998, p. 368.

- ↑ Watson, Alexander: Enduring the Great War. Combat, Morale and Collapse in the German and British Armies, 1914-1918, Cambridge 2008.

- ↑ For an insight into this topic see: Duménil, Anne: De la guerre de movement á la guerre de positions. Les combattants allemands, in: Horne, John (ed.): Vers la Guerre Totale. Le Tournant de 1914-1915, Paris 2010, pp. 53- 77.

- ↑ Jones, Violence Against Prisoners of War 2011, p. 326.

- ↑ Niall Ferguson has argued that it was relatively frequent: Ferguson, Niall: Prisoner Taking and Prisoner Killing in the Age of Total War. Towards a Political Economy of Military Defeat, in: War in History, 11 (2004), pp. 148-92.

- ↑ Kramer, Alan: Dynamic of Destruction. Culture and Mass Killing in the First World War, Oxford 2007, p. 63.

- ↑ Brown, Patricia: In the Hands of the Turk. British and Dominion Prisoners from the Ranks in the Ottoman Empire, 1914-1918, MA Research Thesis, University of Leeds, 2012, Appendix B, p. 114.

- ↑ Doegen, Wilhelm: Kriegsgefangene Völker. Der Kriegsgefangenen Haltung und Schicksal in Deutschland, Berlin 1921, p. 29.

- ↑ Panayi, Panikos: Prisoners of Britain. German Civilian and Combatant Internees during the First World War, Manchester 2012.

- ↑ Nagornaja, Oxana: United by Barbed Wire. Russian POWs in Germany, National Stereotypes, and International Relations, 1914–22, in: Kritika. Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History, 10/3 (2009), p. 477.

- ↑ Ibid, p. 480; also Jones, Violence Against Prisoners of War 2011, pp. 89-90.

- ↑ Rachamimov, POWs and the Great War 2002, p. 88.

- ↑ Kramer, Prisoners in the First World War 2010, p. 80.

- ↑ Harrison, Mark: The Medical War. British Military Medicine in the First World War, Oxford 2010, p. 135.

- ↑ Ibid, p. 284.

- ↑ Nagornaja, United By Barbed Wire 2009, p. 489.

- ↑ Kramer, Prisoners in the First World War 2010, p. 78.

- ↑ Rachamimov, POWs and the Great War 2002, p. 92.

- ↑ Kramer, Prisoners in the First World War 2010, p. 78.

- ↑ Ibid, p. 83.

- ↑ Tortato, Alessandro: La Prigionia di Guerra in Italia, 1914-1919, Milan 2004.

- ↑ Kramer, Prisoners in the First World War 2010, p. 82.

- ↑ Westerhoff, Christian: Zwangsarbeit im Ersten Weltkrieg. Deutsche Arbeitskräftepolitik im besetzten Polen und Litauen 1914-1918, Vienna et al. 2012.

- ↑ Cabanes, Bruno: The Great War and the Origins of Humanitarianism, 1918-1924, Cambridge 2014.

- ↑ Proctor, Tammy: Civilians in a World at War. 1914-1918, New York 2010, p. 172.

- ↑ Nagornaja, United by Barbed Wire 2009, p. 479.

- ↑ Parliamentary Paper, Misc. no. 6, 1918, Correspondence with the German Government respecting the death by burning of J. P. Genower, Able Seaman, when prisoner of war at Brandenburg camp, London 1918.

- ↑ Jones, Heather: Prisoners of War, in: Winter, Jay (ed.): The Cambridge History of the First World War 2014, p. 281.

- ↑ Jones, Violence Against Prisoners of War 2011, pp. 70-119.

- ↑ Nagornaja, United by Barbed Wire 2009.

- ↑ Ibid, p. 485.

- ↑ Procacci, Soldati e Prigionieri 2000.

- ↑ Tortato, La Prigionia di Guerra in Italia, 2004; Gorgolini, Luca: I Dannati dell’Asinara. L’Odissea dei prigionieri austro-ungarici nella Prima Guerra Mondiale, Turin 2011.

- ↑ See the 1914-1918-online article: Prisoners of War and Internees (South East Europe) by Bogdan Trifunovic. See also: Weiland, Hans / Kern, Leopold: In Feindeshand. Die Gefangenschaft im Weltkriege in Einzeldarstellungen, vol. 2, Vienna 1931, Appendix: Kriegsgefangene und Zivilinternierte in den wichtigsten kriegführenden Staaten.

- ↑ Jones, Heather: Imperial Captivities. Colonial prisoners of war in Germany and the Ottoman Empire, 1914-1918, in: Das, Santanu (ed.): Race, Empire and First World War Writing, Cambridge 2011, pp. 177-8.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Yanikdag, Yucel: Healing the Nation. Prisoners of War, Medicine and Nationalism in Turkey, 1914-1939, Edinburgh 2013.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid; Rachamimov, POWs and the Great War 2002; Pörzgen, Hermann: Theater ohne Frau. Das Bühnenleben der Kriegsgefangenen Deutschen, 1914-1920, Königsberg 1933.

- ↑ Pöppinghege, Rainer: Im Lager unbesiegt. Deutsche, englische und französische Kriegsgefangenen-Zeitungen im Ersten Weltkrieg, Essen 2006.

- ↑ Rachamimov, POWs and the Great War 2002.

- ↑ Vischer, A.L.: Die Stacheldraht-Krankheit. Beiträge zur Psychologie des Kriegsgefangenen, Zurich 1918.

- ↑ Hirschfeld, Magnus (ed.): Sittengeschichte des Weltkrieges, 2 vols, Leipzig et al. 1930.

- ↑ Jones, Violence Against Prisoners of War 2011, pp. 296-304.

- ↑ Nagornaja, United by Barbed Wire 2009.

- ↑ Leidinger, Hannes: Gefangenschaft und Heimkehr. Gedanken zu Voraussetzungen und Perspektiven eines neuen Forschungsbereiches, Zeitgeschichte (Austria), 25 (1998), pp. 333-42; Leidinger, Hannes / Moritz, Verena: Österreich-Ungarn und die Heimkehrer aus russischer Kriegsgefangenschaft im Jahr 1918, Österreich in Geschichte und Literatur, 6 (1997), pp. 385-403.

- ↑ Abbal, Odon: Un combat d’après-guerre. Le statut des prisonniers, Revue du Nord, 80, 325 (1998), pp. 405-16.

Selected Bibliography

- Becker, Annette: Oubliés de la Grande guerre. Humanitaire et culture de guerre, 1914-1918. Populations occupées, déportés civils, prisonniers de guerre, Paris 1998: Éd. Noêsis.

- Feltman, Brian K.: Tolerance as a crime? The British treatment of German prisoners of war on the Western Front, 1914-1918, in: War in History 17/4, 2010, pp. 435-458.

- Hinz, Uta: Gefangen im Grossen Krieg. Kriegsgefangenschaft in Deutschland 1914-1921, Essen 2006: Klartext Verlag.

- Jones, Heather: Violence against prisoners of war in the First World War. Britain, France, and Germany, 1914-1920, Cambridge; New York 2011: Cambridge University Press.

- Kramer, Alan: Prisoners in the First World War, in: Scheipers, Sibylle (ed.): Prisoners in war, Oxford; New York 2010: Oxford University Press, pp. 75-91.

- Nachtigal, Reinhard: Kriegsgefangenschaft an der Ostfront 1914 bis 1918. Literaturbericht zu einem neuen Forschungsfeld, Frankfurt a. M.; Oxford 2005: P. Lang.

- Nagornaja, Oxana Sergeevna; Mankoff, Jeffrey: United by barbed wire. Russian POWs in Germany, national stereotypes, and international relations, 1914–22, in: Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History 10/3, 2009, pp. 475-498.

- Pöppinghege, Rainer: Im Lager unbesiegt. Deutsche, englische und französische Kriegsgefangenen-Zeitungen im Ersten Weltkrieg, Essen 2006: Klartext.

- Procacci, Giovanna: Soldati e prigionieri italiani nella Grande Guerra. Con una raccolta di lettere inedite, Rome 1993: Editori riuniti.

- Rachamimov, Alon (Iris): POWs and the Great War. Captivity on the Eastern front, New York 2002: Berg Publishers.

- Speed, Richard Berry: Prisoners, diplomats, and the Great War. A study in the diplomacy of captivity, New York 1990: Greenwood Press.