Introduction↑

This article describes how German and Austro-Hungarian prisoners of war passed their time in captivity in Japan during the First World War (WWI). According to Heather Jones, captivity and prisoner camps are among the most under-researched themes in WWI studies.[1] Only in the last decade have historians begun to study captivity in more detail.[2]

Despite the recent upsurge in interest in captivity in Japan during WWI, very little research has been conducted on WWI POWs, with the exception of distinguished studies about the Bando POW camp.[3] Since the publication of the Bando POW camp studies, further works on the POW camps in Kurume, Narashino, Aonogahara, Osaka, Ninoshima and Nagoya have emerged, as well as a journal on POW studies.[4] While the following article owes much to these preceding studies, it also attempts to locate the prisoners’ experience in Japan as an integral part in the greater story of worldwide captivity during the First World War. Such perspective was lacking in the previous studies, which were particularly, if not exclusively, interested in German-Japanese cultural relations. This article focuses on the organization of POW camps and POWs’ everyday lives in Japan, focusing on German and Austrian-Hungarian POWs.

Internment↑

Following the outbreak of war between the Entente and Central Powers, Japan declared war against Germany, which had previously colonized the Chinese port city Tsingtao and its surroundings at the end of the 19th century. When Germany and its allies were defeated in Tsingtao, their soldiers were captured and sent to Japan. More than 4,600 prisoners of war were interned in temporary camps in cities throughout Japan (Kumamoto, Kurume, Fukuoka, Oita, Marugame, Matsuyama, Tokushima, Himeji, Osaka, Nagoya, Shizuoka and Tokyo). Ultimately eighty-seven prisoners died in captivity.[5]

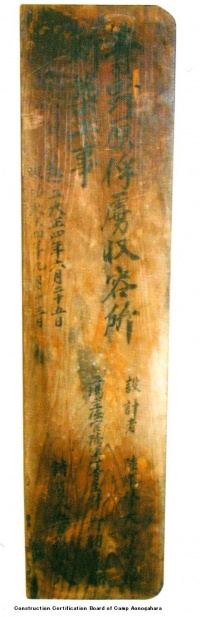

In 1915, with no end in sight to the war, the Japanese military authorities decided to construct permanent POW camps to make life more tolerable for the prisoners. This improved version of the POW camp was constructed in Kurume, Aonogahara (Hyogo-ken), Nagoya and Narashino (Chiba-ken). Accordingly, former POW camps in Kumamoto, Fukuoka, Himeji and Tokyo were closed. In 1917 the POW camp Ninoshima (off Hiroshima) was established in order to absorb prisoners from Camp Osaka, and the POW camp Bando was created in order to integrate the camps of Marugame, Matsuyama and Tokushima. The POW camps of Shizuoka and Oita remained untouched until the last year of war, when prisoners there were deported to Narashino.

POW Camps↑

A POW camp usually consisted of offices, guardrooms, mess halls, sick bays, laundries, bath houses and barracks. They were regularly visited by representatives of the protecting countries: in the beginning the USA fulfilled this role, and then, starting in February 1917, the Netherlands took over for Germany and Spain for Austria-Hungary. The International Red Cross was also involved in reviewing prisoners’ living conditions.

Each camp had its own characteristics. Camp Kurume was the largest in Japan, with 1,308 German prisoners, of which fifty-nine were officers, and forty-seven Austro-Hungarians. Japanese regiments recruited from this region had been mobilized to attack German fortresses in Tsingtao and had suffered heavy casualties, so prisoners in this camp were very strictly controlled by camp officials. Even so, musical events were more frequently organized in Camp Kurume than in any other camp. This fact suggests that POWs there were also treated in accordance with military authorities’ principles. Today we are still able to examine almost all the programs played by prisoners’ orchestras.

Camp Ninoshima, with 536 Germans and nine Austro-Hungarians, was isolated from the Japanese inhabitants because the island was situated off of Hiroshima and surrounded by high walls lest anyone see the naval port nearby.

In Camp Aonogahara, near Kobe, there were 255 German and 230 Austro-Hungarian prisoners, constituting some 80 percent of Austro-Hungarians interned in Japan. Reflecting the ethnic composition of Austria-Hungary, the prisoners of Aonogahara were a complex mosaic of ethnicities. This helps to explain why tensions among them were easily exacerbated by minute differences in living conditions.

On Shikoku Island there were three camps: Marugame, Matsuyama and Tokushima, which were integrated into Camp Bando in 1917. Camp Bando, with 918 German soldiers and twenty German officers, was the second largest POW camp in Japan and maintained many of the cultural activities of the former individual camps. Camp Bando prisoners issued a newspaper, Baracke, which incorporated pre-existing newspapers like the Tokushima Anzeiger. There was a whole host of cultural organizations, Engel’s Orchestra perhaps the most famous of them all.

Because Camp Nagoya, housing 494 German soldiers and twelve German officers, was situated in a city center, it was able to provide prisoners with workplaces such as machine shops, flourmills and metal plating industries.

Camp Narashino’s geographical location close to Tokyo made it a model camp, regularly visited by staff from other camps. 546 Germans and two Austro-Hungarians were interned there when it was first established.

Labor↑

In contrast to the European belligerent countries, Japanese authorities were not forced to employ prisoners of war to fill gaps in the labor market. This was in no small part due to the fact that Japan was far from the European battlegrounds and local workers were not drafted for the army. Nevertheless, the Japanese authorities were eager to make use of the prisoners’ developed skills. For this reason, the government ordered that a list be made of available technical engineers. Despite this, permanent camps were mostly located far from city centers, and their residents were not readily available for work, with the exceptions of Kurume and Nagoya.

In Kurume the prisoners’ work contributed to the development of the local rubber industry, which served as a basis for the now world-famous tire manufacturer Bridgestone.

In Nagoya there were many opportunities for prisoners to work. A report by the International Red Cross suggested that prisoners were very fond of working in industry,[6] not only to escape the monotonous everyday life of the POW camp, but also to earn money to improve their living conditions. In Nagoya City, prisoners’ advanced engineering skills contributed to the development of many branches of industry, such as machine, food and metal plating industries. To cite only one example, a prisoner named Heinrich Freundlieb (1884–1955) was employed in the flour milling industry to make advances in bread baking techniques. After the war, he decided to remain in Japan and later established his own workshop in Kobe, which became one of the most celebrated bakeries in that area.

Sports and Cultural Activities↑

From the very beginning, the prisoners’ favorite sport was football. Football matches were played against fellow POW teams and local club teams, composed of residents and high schools. These matches often attracted crowds of spectators. Prisoners also enjoyed organizing Turnvereine (gymnastics clubs) to provide opportunities for exercise and promote good health.

Most prisoners were ultimately interned in Japan for five years. Without these diversions, their fate might have been bleaker. Prisoners were also generally allowed to have excursions once a week to places such as temples and shrines. They had to march in two columns and were escorted under guard, but still managed to enjoy the beautiful landscape and feel somewhat emancipated.

Thanks to the presence of celebrated musicians and entertainers among the prisoners, theatrical productions and concert parties became a permanent feature of life in the POW camps. A pivotal figure in this respect was Paul Engel (1881-?), who was interned first in Tokushima and then in Bando and organized camp orchestras in both locations. At the farewell ceremony held at the end of 1919, his orchestra played the 9th symphony of Beethoven, which had never before been performed in public in Japan.

Among the newspapers issued by the prisoners, the Tokushima Anzeiger and Baracke are available to researchers thanks to the German House in Naruto. The German House is an organization established on the site of a former POW camp with the aim of promoting cultural exchange between Japan and Germany. The first issue of the Tokushima Anzeiger wrote: “We wish that our newspaper, the Tokushima Anzeiger, brought into the world today will not live long. We rather wish we could leave Japan for our dear homeland and the newspaper would cease to exist.”[7]

It reported in detail on what was occurring on the European battlefield. The section “Tsingtao Diary” described the battle that the prisoners had fought in Tsingtao day by day, and the section “Japanese History” helped them understand the surrounding society. The newspaper shows that the prisoners were not intellectually isolated from the world, despite being surrounded by barbed wire.

The second issue of the newspaper appeared on 11 April 1915. A “lecture concert” was scheduled for that evening. The Tokushima Anzeiger published the program of the lecture concert as follows:

- “The Heavens Are Telling”

Hymn by Beethoven for male voice choir and string orchestra

Sung by Hansen

- Poem “Germany” by H Heine (written in summer 1840)

- Poem “The French” by H. F. Urban (melodramatic)

- “How Peter Pein escaped the English” Account by Kurt Küchler

- “Sailors’ Lot” and “Heather Rose”

male voice choir “Germania”

- Poem “Pleasure of Domesticity” by A. Mosykowski [Alexander Moszkowski]

- “How Did the Prussians Penetrate Bohemia in 1866” by Mercell [Marcel] Salzer

- Song “Lützow’s Wild Hunt”

- “Our Enemies,” text and drawing by Ruff, Ob. Mtr. Artl. D. Res. [Obermatrosenartillerist der Reserve]

- Poem “ A couple of questions for John Bull” by Goren Fook [sic]

- Music[8]

This program shows the extent and variety of the entertainment conducted by prisoners throughout Japan.

Exhibitions of Arts and Handicrafts↑

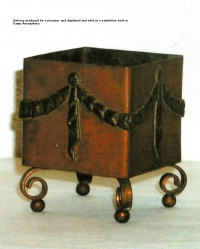

Prisoners displayed the results of their cultural activities to the Japanese public by way of exhibitions open to local residents. Prisoners’ art and handicrafts were also available for purchase. Though few in number, the surviving examples of these works are vivid relics of the prisoners’ lives in Japan.

The first exhibition was held in Bando in March 1918 and was followed by exhibitions at other camps. Camp Ninoshima, located off Hiroshima, decided to hold an exhibition in the city center in March 1919. The exhibition site was the recently completed Hiroshima Industry Exhibition Center. Because the building itself was designed by the Austro-Hungarian architect Jan Letzel (1880–1925), the structure’s atmosphere combined with the prisoners’ works made people feel as though they were in Europe. The exhibition was visited by more than 10,000 people, and prisoners’ arts and handicrafts were sold on the spot, most of them purchased by the Industry Exhibition Center itself. Unfortunately, when the atomic bomb struck Hiroshima on 6 August 1945, the Industry Exhibition Center suffered a direct hit. The ruins of the building are now well known as the Atom Bomb Dome. The prisoners’ arts and craftwork shared the building’s fate and were lost.

Tensions and Punishment↑

Germans and Austro-Hungarians were interned in Camp Aonogahara, and as Austria-Hungary was made up of many nationalities, the internees were a complex mix of ethnic groups. There had already been racial tensions in the Himeji POW camp between Austria-Hungary’s Italian minority and other Austrian-Hungarians after Italy’s entry into the war on the side of the Entente. Toward the end of the war, Austro-Hungarian men who had been repatriated from Russian POW camps after the Bolshevik Revolution led insurrections in their homeland. News of the insurrections in Austria caused violent struggles between supposed South Slavs and other Austro-Hungarians in Japanese camps.[9]

Although the issue of punishment of prisoners during the First World War is an important one, it is studied much less in comparison to punishment in captivity in the Second World War. The Japanese military authorities’ reports suggest that the prisoners were not treated unfairly. In Camp Kurume twenty-one prisoners were declared guilty and sentenced to jail between January and September 1916. To cite some instances:[10] A prisoner who illegally purchased whisky was sentenced to five days of heavy imprisonment.

A prisoner who testified inaccurately about the escape of his fellow prisoner was sentenced to three days of heavy imprisonment.

A prisoner who did not obey fire prevention regulations was sentenced to three days of heavy imprisonment.

A prisoner who overslept and was absent during roll call was sentenced to three days of heavy imprisonment.

Prisoners who conspired to escape were sentenced to eighteen months of custody.

A prisoner found in possession of a saw against regulations was sentenced to three days of heavy imprisonment.

A prisoner who answered for other officials during roll call was sentenced to ten days of heavy imprisonment.

A prisoner who gave meat to a Japanese trader and behaved arrogantly when questioned was sentenced to thirty days of heavy imprisonment.

Food Supplies↑

Japanese authorities spent thirty sen per soldier for food supplies daily, which was equivalent to the daily wages of ordinary workers, and forty sen per officer. Camp Bando’s camp command recorded food supplies for some 900 prisoners per week in 1918 as follows:[11]

| Bread | 2,655 kg | Potatoes | 2,887 kg |

| Beef | 450 kg | Pork | 75 kg |

| Cabbage | 375 kg | Beans and Peas | 510 kg |

| Onions | 105 kg | Leeks | 11 kg |

| Butter | 41 kg | Rice | 285 kg |

| Eggs | 101 kg | Fish | 137 kg |

| Beets | 187 kg | ||

Based on the records above, calories per capita per day were around 2,520. Additionally, prisoners were allowed to cultivate their own fields and raise poultry and pigs in order to supplement their food supplies.

Prisoners in Bando engaged in collective farming to grow all kinds of vegetables. Their innovative farming techniques were adopted by local peasants. For the prisoners in Aonogahara, raising pigs served both as a means of sustenance and exercise. Because the pigsty was located 800 meters away from the camp, Japanese guards accompanied prisoners when they went to take care of the pigs. The prisoners slaughtered the pigs and processed pork and sausages themselves.

Repatriation, No Return, the Deceased↑

On 11 November 1918, when the armistice on the Western Front ended WWI, more than 4,600 prisoners in the POW camps of Japan were awaiting repatriation to their homelands. Czechs and Slovaks were the first to be set free in April 1919. They were followed by prisoners from other newly established successor states or territories incorporated into the Entente countries. Finally, at the end of 1919 and beginning of 1920, prisoners from Germany, Austria and Hungary were sent home.

Some people chose not to return. Prisoner Paul Kalkbrenner is one such individual. He was interned in Camp Nagoya and engaged in cultivating the camp fields and raising chickens and rabbits. After the war he and his colleagues decided to go to Korea with a Japanese agriculturalist, Shinshichiro Nomura (1880–1946), to establish a German firm which they hoped would contribute to the development of Korean agriculture.[12]

Those who passed away during internment in Japan were mostly buried in military cemeteries nearby. Their graves can still be found today in the military cemeteries of Osaka, Narashino, Kurume, Bando, Himeji and so on.

Conclusion↑

During the First World War, more than 4,600 German and Austro-Hungarian prisoners of war were interned in Japan. Although strictly controlled by the Japanese military authorities, they were treated as fellow soldiers in accordance with the Hague Convention.

For example, they enjoyed football matches not only among themselves but also against local club teams. Prisoners were also generally allowed to go on weekly excursions. Theatrical productions and concert parties were regular features of life in POW camps, and local residents often participated in these activities. Camp newsletters reported minutely upon what was occurring on European battlefields. While the prisoners were physically surrounded by barbed wire, they were not intellectually isolated from the surrounding world. They often enjoyed opportunities to work outside the camp in order to escape the monotony of everyday life and to earn money to improve their living conditions.

Despite such humane treatment, each of the final reports issued at the closure of the camps stated that the camp administration should make the prisoners’ lives more comfortable in the future. It is regrettable that these recommendations were not respected in WWII.

Atsushi Otsuru, University of Kobe

Section Editors: Akeo Okada; Shin’ichi Yamamuro

Notes

- ↑ Jones, Heather: A Missing Paradigm? Military Captivity and the Prisoner of War, 1914–18, in: Stibbe, Matthew (ed.): Captivity, Forced Labour and Forced Migration in Europe during the First World War, London/New York 2009, p. 19.

- ↑ Otsuru, Atsushi: Horyo ga Hataraku-toki [POW at Work], Kyoto 2013.

- ↑ Muneta, Hiroshi: Bando Huryo Shuyosho Monogatari [A History of the POW Camp Bando]: Nihonjin to Doitujin no Kokkyo-wo Koeta Yujo [Friendship beyond the Border], Tokyo 2006.

- ↑ Chintao-sen Doitsuhei-Huryo Shuyosho Kenkyu: Studies of German POWs in Japan after the War of Tsingtao, 2003.

- ↑ Seto, Takehiko: Daiichiji-Taisenji no Ninoshima Huryo-Shuyosho [Ninoshima POW Camp during WWI], in: Rinkai-chiiki ni Okeru Senso: Koryu, Kaiyo-seisaku [Coast and Contact: War, Exchange and Politics in a Maritime World], Kochi-City 2011, p. 285.

- ↑ Comité International de la Croix Rouge Genéve: Agence des Prisoniers de Guerre. Kurzer Bericht über die Eindrücke der 7. Lagerreise April/Mai, 1918.

- ↑ "Und ein langes Leben wünschen wir unserer Zeitung durchaus nicht; denn an dem Tage, an dem wir zum Tore unseres Lagers hinausziehen, um die Reise nach den [sic] lieben deutschen Heimat anzutreten, soll sie ihre [sic] Erscheinen einstellen." German House (ed.): Tokushima Anzeiger, Naruto-shi 2012, No. 1 (5. April 1915), p. 1; online: http://www.djg-lueneburg.de/files/TA1-01.pdf (retrieved: 4 April 2013).

- ↑ German House (ed.): Tokushima Anzeiger. Naruto-shi 2012, No. 2 (11. April 1915), online: http://www.djg-lueneburg.de/files/TA1-02.pdf (retrieved: 4 April 2013).

- ↑ Otsuru, Atsushi / Hukushima, Yukihiro / Hujiwara, Tatsuo: Aonogahara Huryo Shuyosho no Sekai [The World inside the POW Camp Aonogahara]. Daiichiji Sekai-Taisen to Osutoria Horyohei [Austrian Prisoners in WWI], Tokyo 2007, p. 143ff.

- ↑ Kurume-shi Kyouikuiinnkai (ed.): Kurume Huryo-Shuyosho 1914–1920 [POW Camp in Kurume], Kurume 1999.

- ↑ Weiland, Hans / Kern, Leopold: In Feindeshand. Die Gefangenschaft im Weltkriege in Einzeldarstellungen, 2 volumes, Wien 1931, p. 83.

- ↑ Menjo, Yoshio: Higashi-ku ni Atta Huryo-Shuyosho [POW Camp in Higashi-ku Nagoya], in: Higashi 12 (2012), pp. 5-51.

Selected Bibliography

- German House (ed.): Tokushima-Anzeiger, 1915.

- Jones, Heather: A missing paradigm. Military captivity and the prisoner of war, 1914-18, in: Stibbe, Matthew (ed.): Captivity, forced labour and forced migration in Europe during the First World War, 2009, pp. 19-48.

- Klein, Ulrike: Deutsche Kriegsgefangene in japanischem Gewahrsam, 1914-1920. Ein Sonderfall, thesis, Freiburg 1993: Universität Freiburg.

- Kyouikuiinnkai, Kurume-shi (ed.): Kurume Huryo-Shuyosho 1914–1920 (POW Camp in Kurume), Kurume 1999.

- Menjo, Yoshio: Higashi-ku ni Atta Huryo-Shuyosho (POW Camp in Higashi-ku Nagoya), in: Higashi/12 , 2012, pp. 5-51.

- Narashino-shi Kyoikuiinkai (Narashino City School Board) (ed.): Doitsu-heishi no Mita Nippon. Narashino Huryo-Shuyousho 1915-1920 (Japan as experienced by German soldiers. POW Camp Narashino 1915-1920), Tokyo 2001: Maruzen.

- Osaka Huryo Shuyosho Kenkyukai (ed.): Osaka Huryo Shuyosho no Kenkyu (POW Camp Osaka Studies). Taisho-ku ni Atta Daiichiji-Taisen-ka no Doitu-hei Shuyosho (A POW camp existed in Taisho District during WWI), Osaka 2008.

- Otsuru, Atsushi: Aonogahara furyo shuyojo no sekai. Daiichiji Sekai Taisen to Osutoria horyohei (The world inside the POW camp Aonogahara), Tokyo 2007: Yamakawa Shuppansha.

- Paravicini, Jakob August Friedolin, Internationales Komitee vom Roten Kreuz (ed.): Dokumente herausgegeben während des Krieges 1914-1918. Bericht des Herrn Dr. F. Paravicini, in Yokohama über seinen Besuch der Gefangenenlager in Japan (30. Juni bis 16. Juli 1918), Wetter 2005: DJG.

- Rinkai-chiiki ni Okeru Senso: Rinkai chiiki ni okeru sensō kōryū kaiyō seisaku (Coast and contact. War, exchange and politics in a maritime world), Kochi-City 2011.

- Seto, Takehiko: Daiichiji-Taisenji no Ninoshima Huryo-Shuyosho (Ninoshima POW Camp during the First World War): Rinkai-chiiki ni Okeru Senso. Koryu, Kaiyo-seisaku (Coast and contact. War, exchange and politics in a maritime world), Kochi-City 2011, pp. 279-315.

- Toda, Hiroshi: Bando Huryo-Shuyosho Monogatari (A Tale of the POW Camp Bando). Nihon-jin to Doitsu-jin no Kokkyo wo Koeta Yujo (Friendship Beyond the Borders Between Japan and Germany), Tokyo 2006.

- Tsintao-sen Doitsu-hei Huryo Shuyosho Kenkyu-kai (Battle of Tsintau and POW Camps Studies Asociation) (ed.): Tsintao-sen Ditsu-hei Huryo Shuyosho Kenkyu (Battle of Tsintau and POW camps studies), 2007.

- Weiland, Hans / Kern, Leopold (eds.): In Feindeshand. Die Gefangenschaft im Weltkriege in Einzeldarstellungen, Vienna 1931: Bundesvereinigung der ehemaligen österreichischen Kriegsgefangenen.