The Outbreak of War↑

The Italian Theatre↑

Italy’s calculated decision for war in spring 1915 put her armed forces into a difficult position. A rapid victory against Austria-Hungary was vital, since the Italian public were not enthusiastic about the war and the army was not really ready to undertake a prolonged conflict. An offensive was essential for political reasons: both the Italian and Allied governments demanded it, while practical considerations also applied, as it was hoped that victory could be achieved quickly before Germany intervened against Italy. While strategically Italy was obliged to take the offensive, the geography of the Italo-Austrian border imposed serious constraints. Italy sought to claim lands which it saw as rightfully Italian: Trento and the South Tyrol as far as the Brenner Pass, along with Trieste and the Austrian Littoral as well as northern Dalmatia. However, the direct conquest of these areas – the so-called terre irredente (unredeemed lands) still under Austrian rule – would not be straightforward. In the northern Alpine sector, the only area which appeared promising for operations was the relatively accessible plateau known as the Altopiano d’Asiago, ringed on all sides by heavily fortified mountain ranges which blocked the Italian path towards Trento and the Tyrol. Given the political and cultural importance attached to the area, a key patriotic focus, it was essential for Italy to fight vigorously in the Alps, yet in military terms the area was extremely challenging. From the Trentino, the border ran northeast though the virtually impassable ranges of the Dolomites and Carnic Alps, where there was little chance of carrying out a successful attack. The best prospect for an Italian offensive lay in the east, where the terrain flattened somewhat into a series of rolling hills and valleys along the line of the river Isonzo from Plezzo (Bovec) southwards, through the town of Gorizia and towards the barren and rocky Carso plateau. The lower Isonzo in particular, between Gorizia and the sea, was identified by the Italian command as the most likely place for a breakthrough. Chief of the General Staff Luigi Cadorna (1850-1928) drew up plans to attack eastward into Slovenia to capture Ljubljana as well as Trieste, before eventually turning northwards for an assault on Vienna. These plans were ambitious, especially given that the Western Front was already entrenched and immobile by the spring of 1915, but Cadorna did not believe that the difficulties of offensive breakthroughs in that theatre would also apply in his own theatre. At both operational and tactical levels he remained committed to a doctrine of the offensive as Italy began the war.[1] In reality, given the constraints of geography and of the Italian political situation, he had few strategic options available to him.

If Cadorna’s options were limited, they were also easily guessed at by Austria-Hungary. Her Chief of General Staff, Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf (1852-1925) had unsurprisingly identified the lower Isonzo as the most likely area for an Italian offensive, though during the period of Italian neutrality from August 1914 to May 1915 he chose to act cautiously so as not to undermine the precarious peace between the two states. There were few fortifications along the Isonzo front before 1914, so a defensive line based on field fortifications, wire and minefields was hastily constructed, in particular around the plateaus of the Bainsizza and the Carso. The Altopiano [plateau] d’Asiago in the Trentino was much better protected, with a string of armoured fortresses backed up by a solid communications network.[2] These fortifications were vital. Austria could spare relatively few troops for the Italian front in spring 1915 after the heavy losses of the Galician and Carpathian campaigns. Although German support on the Eastern Front would help to alleviate the pressure, it was not until the end of 1915 that the Hapsburg army was able to transfer a significant quantity of troops to the Italian theatre. Instead they would rely on both the natural advantage of higher ground and on the well-developed defensive systems created along the entire front in order to negate the numerical superiority which the Italian army had in the first year of the war. However, while strategically on the defensive, Austria-Hungary did not perceive the Italian theatre as unimportant. Conrad was a vigorous Italophobe, keen to see Italy as the Empire’s main enemy, while resentment at Italy’s perceived betrayal after thirty years of alliance also fuelled popular anger.[3]Kaiserlich und Königlich (K.u.K., Imperial and Royal) soldiers of nearly all ethnic or linguistic backgrounds were keen to fight against Italy in 1915.[4]

The Adriatic↑

Directly alongside the Isonzo front, the major focus of operations on land, was the chief area for Italy and Austria’s war at sea: the Adriatic. Naval operations there began before Italy herself joined the war. In August 1914 the French fleet entered the Adriatic with the intention of attacking the Austrian fleet and supporting France’s allies in the Balkans, Serbia and Montenegro; at the very least, France aimed to confine the K.u.K. Kriegsmarine (navy) within the Adriatic. Austria had two major naval bases in the Adriatic: Pola to the north, at the tip of the Istrian peninsula, and the Gulf of Cattaro (also known as the ‘Bocche‘) in the south. The latter, a naturally defensible harbour benefiting from strong outer fortifications, was worryingly close to Montenegro and threatened transport of supplies into the Balkans. However the French High Command was not keen to commit to major operations in the Adriatic and the French force based on Corfu mostly limited itself to blockading the entrance below the Straits of Otranto during the winter of 1914-15. In this somewhat fruitless endeavour they were joined from 1915 by patrols of British drifters employing nets in an attempt to entangle – or at least locate – submarines. The sinking of the French armoured cruiser Leon Gambetta by an Austrian submarine in April 1915 marked the end of major French involvement in the Adriatic.

Austria’s naval strategy was initially unclear. The commander of the fleet, Admiral Anton Haus (1851-1917), was reluctant to support German ambitions in the eastern Mediterranean, especially after Italy’s declaration of neutrality. Though the Austrian fleet had grown rapidly since 1900, with dreadnoughts and semi-dreadnoughts supplementing its existing cruisers, coastal defence forces and torpedo boats, it remained far smaller than the French Mediterranean fleet which it had no intention of coming out to meet directly. Throughout the period of Italian neutrality Haus prioritised the necessity of keeping Austria’s limited forces within the Adriatic, rightly considering that Italian intervention was a real danger. In the face of this decision, the Germans chose in early 1915 to send their own submarines down to the Mediterranean – first overland, in pieces, and then by sea – to operate out of the Austrian base at Cattaro. From there they did considerable damage to merchant shipping in the months and years to come. Since Italy and Germany were not at war with one another until August 1916, the first period of the war witnessed some confusing renaming and renumbering, as German U-boats sometimes sailed under the Austrian flag.

When Italy renounced its membership in the Triple Alliance and declared war on Austria-Hungary, Haus’ caution seemed justified. On 23 May 1915, he led out the entire fleet to attack Italy’s exposed Adriatic coast, bombarding coastal towns and sinking a destroyer. Ancona province was worst hit, with serious damage to shipyards and an airport as well as dozens of civilian casualties.[5] Italy was unable to retaliate since her fleet was concentrated at Taranto, on the Mediterranean coast. However this raid turned out to be the largest single operation the Austrian fleet would conduct in the war. Further attacks on this scale were not attempted, though her ships and aircraft continued to intermittently bombard the coast, with attacks on Rimini, Bari and Brindisi.

Italy’s own strategic plan for the Adriatic, determined by the chief of naval staff, Vice-Admiral Paolo Thaon di Revel (1859-1948), was broadly defensive: in his view the fleet was too small and vulnerable to risk any major losses, so commanders were advised to act cautiously. The Adriatic fleet was under the command of Vice-Admiral Luigi Amedeo, Duke of the Abruzzi (1873-1933), first cousin to the king (and noted mountaineer and Polar explorer). He initially wanted to launch an offensive against the islands of the central Dalmatian coast but preliminary efforts met with little success and were quickly abandoned. Instead, following Thaon di Revel’s vision, the battle fleet was to be kept at Taranto in case the Austrians chose to send out their own capital ships. Only minor operations were to be conducted in the Adriatic, relying chiefly on submarines, with even destroyers and torpedo boats to be used sparingly to avoid loss or damage by enemy action or poor weather. Meanwhile, significant forces were concentrated near Venice to control the Italian waters of the northern Adriatic, protecting the coastal flank of the Italian army on the lower Isonzo and the Carso. Both Italy and Austria committed to a cautious waiting game, neither side willing to risk precious resources.

1915↑

The Onset of Stasis↑

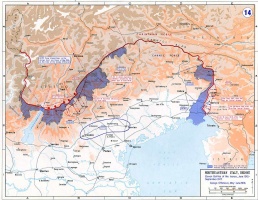

Italy’s early objectives on the Isonzo front were the town of Gorizia and the high ground of the Carso plateau. Attacks were launched to this effect in June and July 1915. The First Battle of the Isonzo began on 23 June 1915 – almost a month after the declaration of war, a delay caused by Italy’s inefficient mobilisation, which enabled Austrian forces to dig in and create effective defences. Assaults were launched on three sections of the Austrian line, but after minimal gains on the western fringes of the Carso fighting halted to allow some reorganisation of the troops. The attack was resumed on 18 July 1915 under the name of the Second Battle of the Isonzo: somewhat artificially, the Italian Supreme Command divided the fighting chronologically into separate battles, but the territory, tactics and troops remained broadly the same. Despite impressive Italian efforts during the period of neutrality to recruit officers and non-commissioned officers (NCOs), acquire artillery, and stockpile munitions, the army was not fully ready for the type of warfare it faced. Repeated frontal infantry assaults were made against the numerous hills and mountains along the front, which have lent their names to a series of ineffectual bloodbaths. By October 1915 (the Third Battle) or November 1915 (the Fourth), little had changed except that heat and thirst gave way to cold and mud. Repeatedly Italian casualties proved heavier than the defenders’ – in the autumn battles the Italians lost 116,000 men against 67,000 Austrians, though of course Italy had the advantage of fighting only on one front.[6] By the end of autumn the Italian forces on the Isonzo were on the verge of collapse. They were saved from disaster only by Austria’s inability to capitalise on their weakness: insufficient troops and a shortage of artillery meant that there was no way for the Hapsburg forces to do more than resist the continuing failed Italian assaults towards the end of 1915.

The other front in this theatre, high in the Alps, was also settling into stasis by the end of the year. Here both armies faced the additional challenges of altitude, snow and ice, vertiginous mountain faces and even the fear of avalanches in a conflict which became known as the ‘White War‘. Italy had an elite mountain corps known as the Alpini, founded in 1872 and numbering eight regiments in 1915. These men had experience in dealing with the extreme Alpine conditions as well as specialist training and equipment (there were even some ski units). However the demands of the front far outstripped the numbers of Alpini available and many ordinary infantry units were sent to the Trentino, where they struggled terribly with the terrain and climate. This mountain warfare, with its unique tactical demands and tremendous human costs, grew to symbolise the conflict in Italian popular perceptions. Though the war in the Italian theatre continued to be bloody and wasteful of human lives, this first year was the worst: tactical misjudgements – such as placing front lines too far forward – were common, while costly errors abounded: trenches and dugouts were inadequate, rations weren’t brought up on time, and basic items of equipment such as boots, helmets and wire-cutters were in desperately short supply.

In October 1915, when Bulgaria entered the war and the Central Powers launched a combined offensive against Serbia, attention turned to the Adriatic. Once Allied terrestrial support was cut off, the only way to transport munitions and supplies to Serbia was overland from Albanian ports – dangerously close to the Cattaro base. Admiral Haus deployed his most effective light craft to the area, where they successfully attacked supply ships bound for Serbia and Montenegro and put pressure on Allied efforts to evacuate the remnants of the Serbian army who had retreated into Albania. The Austrian effort to impede the Allied evacuation, however, had only limited success: on 29 December 1915, while sinking merchant vessels in the port of Durazzo, two of the Austrian fleet’s small number of modern destroyers were sunk by mines, and the rest of the small force only narrowly escaped capture by the Allied light forces based at Brindisi.[7] Throughout the evacuation process of more than 160,000 Serbian troops, in the first few months of 1916, Austrian forces failed to exploit their opportunities to effectively harass and attack the Allies in the southern Adriatic. Their battleships and cruisers did, however, successfully bombard Montenegro into surrender. By spring 1916, with the end of the Balkan campaign, the Adriatic settled into a kind of stasis once again, and Austrian attention could return to the Italian theatre.

1916↑

Operations in the Trentino↑

At the start of 1916 Conrad was free to transfer more troops, including his best divisions, southwards to Italy. However, his hopes of German support were to be dashed, due to their commitments at Verdun and later the Somme. Significant progress had been made in both the quality and quantity of Austrian artillery and munitions by 1916, and heavy artillery and machine guns were increasingly diverted to the Italian front rather than to the East, while elite mountain forces were despatched to the Tyrol.[8] For the first time it would be possible for the Hapsburg forces to be proactive in Italy rather than simply take a defensive position.

Meanwhile Cadorna was obliged to launch an offensive in fulfilment of promises made to the Allies at the Chantilly Conference in December 1915. Under pressure from France to take action, the Fifth Battle of the Isonzo was launched on 9 March 1916. Spring was late in coming that year and the assault began under winter conditions, making a concerted attack very difficult. By this time the Italian army was beginning to improve its equipment and organisation, creating new units and paying particular attention to artillery and machine guns. Gradually changes were also introduced at a tactical level, as the simple frontal attacks of 1915 were to be replaced through 1916 with a more nuanced approach which made better use of the terrain and introduced some elements of infiltration techniques.[9] However these changes had yet to be fully implemented and in fact the attacks of March 1916 were localised, disjointed and ineffective.

Operations in the Isonzo were called off almost immediately as it became apparent that the Austrians were preparing for a huge offensive in the Trentino. This would be known as the Strafexpedition, or ‘punishment expedition’, designed to punish Italy for her ‘betrayal’ of the Triple Alliance. This plan ran counter to German advice. Austria’s ally urged her to turn to the northeast, yet she stubbornly insisted on pursuing an Italian offensive, perhaps encouraged by her dramatic success in the Balkans to focus on the southern rather than the northern theatre, as well as reflecting Conrad’s personal feelings toward Italy. The Trentino front, like the other sectors in the high Alps and Dolomites, had previously been fairly quiet with both sides content to simply occupy their positions most of the time. The Austrian plan was to launch a massive attack into a relatively weakly held area where they hoped to break through onto the plains below, around Vicenza and Padua, and then move eastwards through the Venezia-Giulia region to attack the main Italian forces from the rear.

This attack on the Altopiano of Asiago began on 15 May 1916 and met with immediate tactical success, advancing around twelve miles into the Italian lines. Specialist Austrian mountain troops were deployed effectively, and above all, the build-up of heavy artillery and the use of a concentrated and sustained bombardment ensured that they were able to achieve an impressive initial breakthrough. However the attackers were unable to capitalise on this promising start due to the impossibility of moving up heavy and medium artillery over the broken ground and an insufficiency of fresh troops to maintain momentum, while Cadorna was able to reinforce the Trentino front using his interior lines of communication much faster than the enemy could call up much-needed reserves. Meanwhile the dramatic and rapid success of the Brusilov Offensive in Galicia, launched on 4 June 1916, meant that more Austrian troops had to be sent east in an attempt to halt the Russian advance and the Strafexpedition had to be abandoned, causing great damage to Austrian morale.

A critical legacy of the Austrian failure on the Asiago plateau, combined with the disastrous events on the Eastern front, was the undermining of Conrad’s position, contributing to the creation of a joint military command in the East under German leadership in August 1916. This was followed the next month by the establishment of an overall joint High Command under Wilhelm II, German Emperor (1859-1941). These changes not unnaturally tended to favour a focus on those theatres in which Germany was already engaged. Although Italy finally declared war on Germany on 27 August 1916, it was not a priority for the Germans. The growing political and military dependence of Austria-Hungary on its ally would have significant consequences for the Italian front in 1917.

Italian casualties in the Strafexpedition – 76,000 men – were over double those of the Austrians who lost some 30,000. The Italian troops which had been hastily brought over from the Isonzo front were deployed in a counter-attack, which was in fact a series of separate, poorly planned assaults hoping to seize the initiative and capitalise on the momentary disarray of the enemy. This proved even costlier, with another 70,000 Italian and 53,000 Austrian casualties. In fact the only notable result of these Italian attacks was the loss of the irredentist volunteers Cesare Battisti (1875-1916) and Fabio Filzi (1884-1916), who were captured by Austrian forces on 10 July 1916 and hanged shortly thereafter as traitors. In the process they acquired the status of patriotic martyrs back in Italy. The fallout from these events led to the resignation of the Italian Prime Minister Antonio Salandra (1853-1931) and his replacement by a technical government led by Paolo Boselli (1838-1932).

Attrition on the Isonzo↑

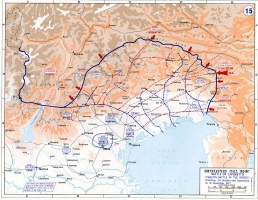

On 6 August 1916 Cadorna returned his focus to his eastern front, where the Sixth Battle of the Isonzo, also known as the Battle of Gorizia, began. This was the first real Italian success of the war: a footing was gained on the Carso around Monte San Michele, Gorizia was taken and a bridgehead secured on the river thanks to the effective use of gas and artillery bombardment. This was primarily due to the Italian intelligence service’s success in concealing the planned attack from the enemy. The victory was not hugely significant in terms of territory but was a great boost to Italian morale, both civilian and military. It proved, for the first time, that an Italian army could defeat a European enemy without foreign assistance.

Fighting continued through the autumn in what were named the Seventh, Eighth and Ninth Battles of the Isonzo. The Italians succeeded in enlarging the bridgehead at Gorizia and gaining ground on the Carso despite poor weather, but these advances were minimal and casualties were very high. A major offensive was out of the question after the triumph of August 1916 and the k.u.k. army defended tenaciously, so these battles had limited objectives and followed the logic of attrition rather than territorial conquest. Reflecting his growing conviction that the enemy must be steadily worn away before any major territorial progress could be attempted, Cadorna called these battles ‘spallate’ – literally shoulder nudges.[10] The Central Powers were also engaged in fighting new combatant Romania, which had entered the war on 27 August 1916 with an invasion of Transylvania which pinned down significant Austrian forces under German command. Though Bucharest was captured by the end of the year and the theatre stabilised thereafter, Austrian offensive options in Italy were limited for the remainder of 1916. Meanwhile the death of Francis Joseph I, Emperor of Austria (1830-1916) in November 1916 removed one of the important bonds of tradition and personal loyalty which helped to maintain cohesion in the multi-ethnic Hapsburg armies.

Kleinkrieg in the Adriatic↑

Submarine warfare in the Mediterranean was a growing threat to the Allied war effort, as Germany stepped up attacks on vital shipping routes and the U-boat flotilla grew. The Allied decision in March 1916 to divide the Mediterranean into zones and allocate responsibility to individual national forces only served to emphasise the relative weakness of the Italian navy compared to the British and French Mediterranean fleets. Until August 1916 the Italians could not, in any case, take direct action against German vessels. The Adriatic, by contrast, was not a major priority for either side, although naval operations continued through 1916 and 1917. The Austrians termed it Kleinkrieg: continual low-level harassment of the enemy by light craft and torpedo boats, coastal bombardments and submarine attacks on merchant shipping and military convoys. Great attention was paid to the Otranto Straits and the drifter line which sought to blockade them though it was never really effective – only one submarine was ever known to have been caught this way.[11] However some important tactical and technological innovations were made: the Austrians deployed Lohner flying boats, successfully sinking a French submarine in September 1916 in what is reputedly the first success of aircraft against submarines.[12] Aerial reconnaissance was also important for both sides. It was used effectively by the Italians in conjunction with their new Mas boats – small, cheap, fast and manoeuvrable wooden craft which could be equipped with torpedoes, ideally suited to the calm conditions of the Adriatic.

1917↑

In March 1917 Conrad was removed from his position as chief of the general staff by Charles I, Emperor of Austria (1887-1922). The new monarch took an increasingly direct role as imperial supreme commander, a change which did little to improve the military efficiency or strategic effectiveness.[13] Campaigning resumed rather late in the spring 1917, despite Cadorna’s agreement to launch a new attack simultaneous to the Nivelle Offensive and Battle of Arras. Supported by British and French heavy artillery, the Italians launched the Tenth Battle of the Isonzo on 12 May 1917, aiming to increase their foothold on the Bainsizza plateau around the Kuk and Vodice mountains north of Gorizia, while simultaneously heading southwards towards the Hermada en-route to Trieste. It was a failure even by the already low standards of the front: the most successful advances, on the flanks, progressed by less than two miles while Italian losses exceeded 128,000, the highest of any month of the war. Forty-one regiments lost over 50 percent of their men and in a few casualty rates were as high as 70 percent in the final week of May 1917.[14] In part this was due to improvements made by the Austro-Hungarian army in training, defensive tactics and in the quality and quantity of their artillery, and in part due to Cadorna’s own failings in command and control. To distract from this fiasco, in June 1917 he ordered a new offensive on the Altopiano, the Battle of Ortigara. A failure to appreciate the different tactical approach required for mountain warfare meant that techniques proven to be successful on the Isonzo were blindly applied to the high Alps with disastrous results. In one part of the line, on the Ortigara itself, the extreme courage of the Alpini enabled them to take a section of the Austrian positions. But this proved untenable since it was a rocky mountain peak entirely exposed to enemy artillery, and the inevitable counter-attack recovered nearly all the ground the Alpini had taken with serious losses to some of Italy’s best attacking forces. Operations on the Asiago front tailed off after the Kerensky Offensive, launched on 1 July 1917, turned Austrian attention eastward, away from the Italian theatre.

The Battle of the Otranto Straits↑

Some of the most important episodes in the Adriatic war took place in the first half of 1917. The resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare adopted by the Central Powers on 1 February 1917 was strongly supported by Admiral Haus, though he would not long live to see its benefits, dying of pneumonia aboard his flagship at Pola just a week later. Under his successor Vice-Admiral Maximilian Njegovan (1858-1930), Austrian submarines contributed to the great success of the new U-boat campaign of March and April 1917, a new strategy which significantly increased pressure on Allied shipping in the Mediterranean. It also served to focus attention ever more closely on the seventy kilometre wide bottleneck of the Otranto Straits, through which Austrian and German craft operating out of Pola and Cattaro passed, heading out of the Adriatic into the Mediterranean. The multinational Allied forces operating out of Brindisi and Taranto had been reorganised in January 1917, strengthening the drifter barrage across the Straits under British command and rerouting major shipping in the Mediterranean to offer better protection, but in the face of the Central Powers’ unrestricted submarine warfare these changes were insufficient. In February 1917 the naval chief of staff Thaon di Revel assumed overall operational command of the Italian fleet in addition to his staff role, replacing the Duke of the Abruzzi. At the Corfu conference on 28 April to 1 May 1917, it was agreed to introduce a dispersed convoy system in the Mediterranean, but discussion on the Otranto Straits was less conclusive. French and Italian enthusiasm for a fixed mine-net barrage was not matched by the British, who would have had to bear much of the costs, and the proposal was left up in the air.[15]

Despite Admiral Njegovan’s general adherence to his predecessor’s defensive strategy in the Adriatic, in May 1917 the K.u.K. Kriegsmarine launched a surprising offensive against the Allied barrage. Given the tonnage successfully sunk by the Central Powers in the Mediterranean in March and April 1917, and Allied ineffectiveness in catching enemy submarines, the barrage appears to have been acting at best as a hindrance or a cause of delay. Nonetheless a raid was planned and launched – perhaps reflecting an irritation among Austrian surface commanders that submarines were getting all the action.[16] Led by the bold and ambitious Captain Miklós Horthy (1868-1957), a rapid raid with air support was planned for the night of 14 May 1917. Three light cruisers were altered to give the appearance of destroyers (hoping to trick the Allies into a less energetic immediate reaction) and these were accompanied by two destroyers and German submarine support. The battle of the Straits of Otranto, as it came to be known, turned out to be the largest battle fought between rival warships in the Mediterranean during the First World War. Horthy, on the Novara, led his raiders to the barrage where they managed to sink over a quarter of the drifters present and damage others, while the destroyers Csepel and Balaton, engaged in diversionary action near the Albanian coast, sank the Italian destroyer Borea which was escorting a convoy transporting munitions and fuel to Valona. As the Allied forces at Brindisi learned of the attack around 04.30 on 15 May 1917, Italian Rear Admiral Alfredo Acton (1867-1934), commanding from the bridge of the HMS Dartmouth, set off with a group of Italian destroyers in pursuit of the Austrian raiders, while the joint Franco-Italian Mirabello group rapidly caught up with the enemy from further south. French and Italian aircraft also attacked the Austrian cruisers, but both the destroyers and the group of cruisers managed to evade the numerically superior Allied forces and despite suffering moderate damage to the Novara and another cruiser the Austrians did not lose a single ship in the operation. In fact, Acton – on the torpedoed Dartmouth - underestimated the extent of the damage inflicted on the enemy and overestimated the reinforcements they had available, and therefore chose to return to Brindisi around midday on 15 May 1917. It is possible that a more vigorous Allied pursuit at this stage might have achieved a decisive victory.[17]

After the battle, the drifters were deployed on the Otranto barrage only during daylight hours and the Central Powers’ submarines continued to operate with considerable ease from their Adriatic bases. Disputes between Italy and Britain over the supply of destroyers to protect the drifters rumbled on through 1917, without ever acknowledging the limited effectiveness of the barrage. However a more effective convoy system and the support of Greek, American and Japanese naval forces in the Mediterranean combined to ensure a steady decline in the impact of submarine action.[18]

The Bainsizza↑

Back on land, the seemingly endless attritional slog on the Isonzo continued. In August 1917 yet another Italian attack was launched, officially the Eleventh, which became known as the Battle of the Bainsizza. This was a surprising success above all for Luigi Capello (1859-1941), the commander of II Army, who had been responsible for the capture of Gorizia the previous year at the head of VI Corps. An experienced staff officer with a background in the infantry, Capello won great praise for this victory within military circles and beyond; he was widely considered to be one of the army’s most talented operational commanders.[19] Ignoring the plans and indeed the orders issued by Cadorna, he took matters into his own hands and succeeded in capturing the whole plateau. This was a severe shock to the Austrian defences, yet due to tactical errors and the inefficiency of the artillery, Italian losses were almost twice those of the Austrians – 160,000 (plus many men sick) to 85,000, with the infantry suffering the most. The battle ended by 12 September 1917, with Cadorna correctly fearing the imminent arrival of German support for the Austrians. Meanwhile domestic unrest was growing in Italy: both Catholics and socialists were increasingly active against the war and economic deprivation was promoting ever greater social tensions. Strikes and anti-war protests had grown progressively more common through the year, and on 22 August 1917 food riots broke out in Turin, led by women and industrial workers. What began as a protest over bread and flour shortages quickly spiralled into widespread anti-war disorder; the authorities opened fire on the rioters, killing more than fifty civilians, and over 900 arrests followed.[20] Both army and country were approaching breaking point.

Catastrophe: The Italian Defeat at Caporetto↑

By the autumn of 1917 the Eastern Front was settling down; in fact, the Bolshevik Revolution was shortly to bring an armistice, long-anticipated by Austria-Hungary. The quietness of this theatre freed up new possibilities for the Central Powers, who were now able to transfer three Austrian and four German divisions from the Austro-Hungarian sector of the front across to Italy. Growing political and economic difficulties within the Hapsburg Empire meant that it was imperative to bring an end to the war as quickly as possible, while the success of previous joint campaigns in the Balkans suggested that a coordinated offensive was the best option. With this in mind, an ambitious offensive was planned under the direction of German general Otto von Below (1857-1944) whose successes on the Eastern Front and in Macedonia made him appear an ideal candidate to head the combined Austro-German 14th Army.

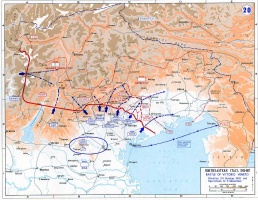

In the early hours of 24 October 1917 a major attack was launched in the mountainous northern sector of the Isonzo front, close to the small town of Caporetto (now Kobarid, in Slovenia).[21] It had been clear for a few weeks that an offensive was imminent – troop and artillery build up had been observed while information from deserters had in fact given the Italian command detailed intelligence on the location, timing and objectives of the operation. Cadorna had issued generic orders to prepare for the defensive in September 1917, though he believed that the main assault would come in the Trentino, with only diversionary actions in the upper Isonzo. The crucial sector of the front was held by Capello’s II Army, composed of twenty-four divisions.[22] Determined and stubborn, Capello was convinced that defensive preparations were unnecessary despite intelligence to the contrary, and indeed he hoped to launch his own offensive before the winter.[23]

The troops in the front lines were taken by surprise when the joint German-Austrian attack began at 02:00 with a brief but accurate and intense bombardment, followed by the main infantry assault at dawn under heavy rain and fog. Fifteen divisions – nine Austro-Hungarian and six German – were involved in the offensive, with the Germans in particular achieving enormous success through innovative infiltration tactics (as previously trialled against the Russians at Riga) and the effective use of gas. They quickly managed to break through at Tolmino and at Conca di Plezzo, with the first troops across the river around 08:00, from where they could outflank whole areas of the Italian defences. By midday they were advancing on Caporetto and by the next day the attacking troops had advanced over twenty-two kilometres and taken some 20,000 prisoners.[24] Tired, demoralised and poorly equipped, the Italians were overwhelmed in many areas, while the Central Powers repeatedly managed to coordinate artillery and infantry to great effect. The vigour of the resistance varied: while some units fought bravely until their defeat was complete and unavoidable, others surrendered almost immediately or fled in panic.[25] Poor planning and organisation meant that the Italians had an almost total lack of reserves in the area and those that were available were not appropriately deployed.

In the course of the initial battle the entire left flank of II Army was forced to abandon its positions, and soon the whole army was in retreat. The lower reaches of the Isonzo were soon affected and III Army, which held this sector, was also forced to retire or risk being totally outflanked. On 27 October 1917, the Supreme Command abandoned its headquarters at Udine. The initial phase of the battle, marked by mass surrender and desertion, proved to be the cause of much controversy both at the time and subsequently. Cadorna, in his bulletin of 28 October 1917, blamed the defeat on "the inadequate resistance of units of 2nd Army, cowardly retreating without fighting or ignominiously surrendering to the enemy, has permitted the Austro-German forces to break our left wing on the Julian front."[26] Politicised interpretations of the battle by contemporaries painted it either as an outbreak of wilful disobedience and defeatism from the insufficiently patriotic masses, or – in the view of the left – as a sign of class struggle and an attempted revolution seeking to end the war.[27] The search for scapegoats took some time and the official inquiry, which was launched almost immediately after the defeat and which released its report in 1919, played its part in blaming Italian officers and men to varying extents.[28] In fact, the Austro-German victory can be attributed chiefly to the successful operational planning and tactical innovations deployed by the attacking troops, as well as poor Italian leadership, staff-work and planning.[29]

Cadorna ordered a full retreat to the line of the Tagliamento River and its bridges began to be destroyed on 30 October 1917, leaving several entire army corps trapped along with thousands of fleeing civilians. This phase of the retreat was extremely disorderly and chaotic, with many thousands of prisoners taken and substantial rates of desertion: many soldiers, convinced that the war was over, downed their weapons and headed for home. As the enemy continued to advance, crossing the Tagliamento in several places, it became clear that this new line would not hold. At the same time the overall situation was beginning to stabilise, units were returning to normal discipline and the retreat was becoming more orderly. The rout was at an end and a new phase of the battle began.[30] By this stage the attacking forces were struggling with overextended supply lines and were beginning to lose momentum. On 4 November 1917 the Italian line withdrew to the Piave River, while IV Army was ordered to come down from the Cadore sector in the far north to join the new front.

By the time the armies were drawn up on the Piave, discipline had fully returned to the Italian forces. Other important changes had also been made: Prime Minister Paolo Boselli had been replaced by the Liberal Vittorio Orlando (1860-1952) while Cadorna had been removed from his position and a new chief of general staff was appointed: Armando Vittorio Diaz (1861-1928). An experienced artillery and staff officer with a much less authoritarian style than his predecessor, Diaz held that improving civil-military relations was a priority and also worked over the following year to improve troop morale through better living conditions and concerted propaganda campaigns. Cadorna’s dismissal was one of the conditions set by the French and the British in return for their support in the crisis,[31] though in fact the incoming prime minister Orlando had already demanded his replacement as a condition of his appointment.[32] At the Rapallo Conference on 6 November 1917 the French and British agreed to send a total of eight French and British divisions to assist Italy, undertaking active duties from 21 November 1917. By this time the battle had entered a final stage, since from 12 November 1917 onwards the Austrians had launched renewed attacks in an attempt to break the now stabilised Piave lines; the Italians defended successfully against these assaults and in the period up to 18 November 1917 even began to launch small scale counterattacks.

When the battle finally ended around 26 November 1917 the Italians had retreated over 150 kilometres in total, abandoning 20,000 square kilometres of territory to the enemy. Second Army had totally disintegrated and its 670,000 men scattered: over 280,000 of them had been taken prisoner and a further 350,000 had absconded, while 40,000 were killed or wounded. In addition 400,000 civilians had fled the newly occupied region, creating a huge refugee problem for the government. Vital equipment was also lost: over 3,000 artillery pieces and a similar number of machine guns were abandoned to the advancing Austrians along with huge quantities of munitions, food, animal fodder, uniforms and medicines.[33]

As the winter weather set in, hampering further offensive operations, the Austrians tried to make the most of their German divisions before they were reassigned to the Western Front. On 5 December 1917 they launched an audacious attack which captured the Meletta Massif but no further progress was made, and fighting halted shortly before Christmas. Austrian troops missed out on their promised Christmas Mass in St. Mark's Cathedral in Venice, but they had come very close.

1918↑

From Defeat to Victory↑

By 1918 Austria-Hungary was beginning to suffer severe civilian hardship and weakening of morale, along with a lack of munitions, food, horses, transport, coal and steel. Her international standing had been boosted by the tremendous success of the Caporetto offensive, but her failure to turn this into a decisive victory over Italy was disappointing, and her participation in the harsh treaties imposed on Romania and Russia alienated international opinion.[34] The long-term viability of the Habsburg Empire itself was by now clearly under question and national divisions within the k.u.k. forces were beginning to become problematic, causing episodes of indiscipline and desertion. Emperor Charles was hoping that the huge German offensive ‘Operation Michael’ in March 1918 would succeed in northwestern France, removing Allied support from the Italians and enabling them to deliver a final crushing blow to capitalise on the gains of Caporetto, but the strategic importance of the Kaiser’s battle was limited. In Italy, the army was being reorganized, re-equipped and retrained with French and British guidance, becoming a much more efficient and tactically improved fighting force, especially in defence. The new front was much shorter and easier to defend, while internal communications and supply were also more straightforward. Little real action was seen in the Italian theatre in this period, though the Italian navy’s new type of MAS boat, first deployed in December 1917, began to raid Austrian shores including Trieste and the Fiume area, while air raids on the major Austrian bases at Pola and Cattaro also put ever increasing pressure on the k.u.k. Kriegsmarine. Renewed Austrian raids against the Otranto barrage were made but with little effect given the greater Allied forces now deployed in the area.

Finally Austria-Hungary launched a last-ditch offensive on 15 June 1918, in what would be known as the Battle of the Piave. Austrian commanders could not agree on a shared strategic plan so forces were divided between a frontal attack on the well-defended Piave positions and an assault from the Asiago plateau towards the plains, a foolish decision which effectively undermined any chance of either attack succeeding. Meanwhile the Italian positions were now well organised with strong support from French and British troops, in particular from aerial forces ready to attack Austrian pontoon bridges over the Piave. Deserters from the k.u.k. along with British intelligence operations had made Diaz aware of the planned offensive well in advance, enabling an effective artillery defence, and the Austrians were ill-prepared. Though there were some initial successes both on the plains and in the Asiago area, these were not followed up, and by 14 July 1918 it was clear that the last Austrian ‘big push’ had failed. A tremendously high number of prisoners were taken and crippling casualties inflicted – though the Italians had lost many prisoners. The consequences to Austrian morale were devastating, and the national divisions within her army were increasingly a source of crisis and mass desertion.

More or less concurrently with the Piave offensive in June 1918 Horthy, now promoted to commander of the Austrian fleet, planned a new offensive on the Otranto Straits. An initial raid by light cruisers would lure out an Allied response, to be followed – at long last – by a major attack by the Austrian heavy ships. If executed, this ambitious plan would have been the largest action in the Adriatic of the entire conflict. However, as four Austrian dreadnoughts moved southwards from Pola, they were spotted by the Italians; the Szent Istvan was sunk by torpedoes from two Italian Mas boats, a major success for Italy. Weakened by this blow and having lost the vital element of surprise, Horthy cancelled the operation. In October 1918 a joint Allied bombardment of the Albanian port of Durazzo was the last significant action in the Adriatic war.

Like the navy, the Austrian armies in Italy were increasingly running out of options. The attack on the Piave was a gamble which proved very costly. They had retreated to a ‘winter line’ at the end of August 1918, but Diaz still feared an autumn offensive. In fact, shortages of food and supplies combined with political unrest at home raised the possibility that Hapsburg troops might need to be withdrawn to maintain domestic order; certainly they were no longer capable of launching another attack.[35] Charles’ first appeal for an armistice was made in September 1918, to no avail. The initiative lay entirely with the Entente. Politically it was essential that the Italians launch a final attack, in order to demonstrate to the Allies that they had beaten the enemy, rather than it seeming that the Austrian army had simply disintegrated. Eventually this political necessity forced Diaz into the Battle of Vittorio Veneto, which was launched on 24 October 1918. Starting with a night attack to capture Papadopoli island in the middle of the Piave river, Italian, French and British troops simultaneously attacked towards Monte Grappa in the north and toward the river Livenza and the town of Vittorio Veneto in the eastern sector. Bad weather hampered initial progress but by 27 October 1918 the main assault had been launched, and by 29 October 1918 the Austrians were in full retreat. The battle of Vittorio Veneto was to some extent a fiction, entailing only a few days of real combat followed by a considerable period of relatively uncontested Allied advance, as the Austro-Hungarian army collapsed rapidly. In the words of Diaz’s ‘Victory Bulletin‘:

The armistice with the Austrian Empire was signed on 3 November 1918 and came into effect a full week before the fighting stopped on the Western Front, at 15:00 on 4 November 1917. Though Austrian troops were still well inside pre-war Italian territory, Italy could claim she had conquered Trieste and the Trentino to finally complete the long process of Italian unification.

Vanda Wilcox, John Cabot University, Rome

Section Editors: Michael Neiberg; Sophie De Schaepdrijver

Notes

- ↑ Cadorna, Luigi: Attacco frontale e ammaestramento tattico, Rome 1915.

- ↑ Rothenberg, Gunther E.: The Army of Francis Joseph, West Lafayette 1998, pp. 188f.

- ↑ Bridge, Francis Roy: The Foreign Policy of the Monarchy, in: Cornwall, Mark (ed): The Last Years of Austria-Hungary. A Multinational Experiment in Early Twentieth-Century Europe, Exeter 2002.

- ↑ Sema, Antonio: La Grande Guerra sull fronte dell’Isonzo, Gorizia 2009, pp. 29-34.

- ↑ Gemignani, Marco: Il bombardamento di Ancona del 24 maggio 1915, in: Bollettino d’Archivio dell’Ufficio Storico della Marina Militare, December 2002.

- ↑ Bencivenga, Roberto: Saggio critico sulla nostra guerra. La campagna del 1915, Rome 1933, pp. 46-49.

- ↑ Halpern, Paul G.: The Battle of the Otranto Straits. Controlling the Gateway to the Adriatic in World War I, Bloomington 2004, p. 8.

- ↑ Rothenberg, The Army 1998, p. 193; also Jeřábek, Rudolf: The Eastern Front, in: Cornwall, Mark (ed): The Last Years of Austria-Hungary. A Multinational Experiment in Early Twentieth-Century Europe, Exeter 2002.

- ↑ Capellano, Filippo / Di Martino, Basili: Un Esercito Forgiato nelle Trincee. L’evoluzione taatica dell’esercito Italiano nella Grande Guerra, Udine 2008, pp. 97-102.

- ↑ Labanca, Nicola: Caporetto. Storia di una disfatta, Florence 1997, p. 25.

- ↑ Halpern, The Battle 2004, pp. 36f.

- ↑ Halpern, The Battle 2004, p. 10

- ↑ Rothenberg, The Army 1998, pp. 203f.

- ↑ Melograni, Piero: Storia Politica della Grande Guerra, Milan 1998, p. 262.

- ↑ Halpern, The Battle 2004, pp. 28-34.

- ↑ Halpern, The Battle 2004, pp. 35-41.

- ↑ Halpern, The Battle 2004, pp. 96-99.

- ↑ Halpern, The Battle 2004, pp. 130-134.

- ↑ Gatti, Angelo: Uomini e folle di guerra, Verona 1929, pp. 224f.

- ↑ Gibelli, Antonio: La Grande Guerra degli italiani, Milan 2002, pp. 219f.

- ↑ For an excellent analysis by a senior staff officer see: Bencivenga, Roberto: La sorpresa strategica di Caporetto, ed. Giorgio Rochat, Udine 1997.

- ↑ See his own 1918 account: Capello, Luigi: Caporetto, perché? La 2. armata e gli avvenimenti dell’ottobre 1917, Turin 1967.

- ↑ Gatti, Angelo: Fra le cause strategiche di Caporetto, in: Gatti, Angelo: Uomini e folle di guerra, Verona 1929, pp. 224f; Isnenghi, Mario / Rochat, Giorgio: La Grande Guerra 1914-1918, Bologna 2008, p. 199.

- ↑ Gatti, Fra le cause 1929, pp. 215f.

- ↑ On surrender and the responsibilities of senior Italian officers, see: Wilcox, Vanda: Generalship and Mass Surrender During the Italian Defeat at Caporetto, in: Beckett, Ian F. W.: 1917. Beyond the Western Front, Leiden 2008.

- ↑ Official bulletin, published in: Relazione della Commissione d’Inchiesta, R. Decreto 12 gennaio 1918: Dall’Isonzo al Piave 24 ottobre-9 novembre 1917, volume II, section 588, Rome 1919.

- ↑ See for example: Malaparte, Curzio: Viva Caporetto! La rivolta dei santi maledetti, Florence 1921.

- ↑ Ungari, Andrea: The Official Inquiry into the Italian Defeat at the Battle of Caporetto (October 1917), in: Journal of Military History, 76/3 (2012) pp. 695-726.

- ↑ Sema, La Grande Guerra 2009, pp. 487-558

- ↑ Bencivenga, La sorpresa strategica 1997, p. 14. Bencivenga identifies the period 24 October – 3 November 1917 as rout and disorder followed by stabilisation 4-12 November 1917.

- ↑ Cadorna spoke of ‘mutual mistrust’ between himself and the Allied Chiefs of General Staff. Cadorna, Luigi: Lettere Familiari, ed. Raffaele Cadorna, Milan 1967, pp. 243f.

- ↑ Isnenghi / Rochat, La Grande Guerra 2008, p. 393.

- ↑ Full details in: Relazione della Commissione d’Inchiesta, Dall’Isonzo al Piave 1919, volume I.

- ↑ Bridge, Foreign Policy 2002, p. 41.

- ↑ Rothenberg, The Army 1998, p. 215.

- ↑ Comando Supremo: Italy’s Victory against Austria. Official War Bulletins and Communiqués, 24th October - 4th November 1918, Rome 1918. p. 39.

Selected Bibliography

- Brignoli, Marziano: Il generale Luigi Cadorna capo di Stato maggiore dell'esercito, 1914-1917, Udine 2012: Gaspari.

- Cappellano, Filippo / Di Martino, Basilio: Un esercito forgiato nelle trincee. L'evoluzione tattica dell'esercito italiano nella Grande Guerra, Udine 2008: Gaspari.

- Di Martino, Basilio: L'aviazione italiana nella grande guerra, Milan 2011: Mursia.

- Favre, Franco: La Marina nella Grande Guerra. Le operazioni navali, aeree, subacquee e terrestri in Adriatico, Udine 2008: Gaspari.

- Halpern, Paul G.: The naval war in the Mediterranean, 1914-1918, Annapolis 1987: Naval Institute Press.

- Isnenghi, Mario / Rochat, Giorgio: La grande guerra, 1914-1918, Scandicci 2000: La nuova Italia.

- Kuprian, Hermann / Überegger, Oswald (eds.): Der Erste Weltkrieg im Alpenraum. Erfahrung, Deutung, Erinnerung / La Grande Guerra nell'arco alpino. Esperienze e memoria, Bozen 2006: Athesia.

- Melograni, Piero: Storia politica della grande guerra, 2 volumes, Milan 1997: Laterza.

- Ministero della Difesa (ed.): L'Esercito italiano nella grande guerra, 1915-1918, 7 volumes, Rome 1927-1988: Provveditorato generale dello Stato, Libreria.

- Monticone, Alberto (ed.) / Gatti, Angelo: Caporetto. Dal diario di guerra inedito (maggio-dicembre 1917), Bologna 1965: Il Mulino

- Morselli, Mario: Caporetto, 1917. Victory or defeat?, London; Portland 2001: F. Cass.

- Pieri, Piero / Valeri, Nino: L'Italia nella prima guerra mondiale, 1915-1918 (L'edizione riveduta e ampliata di un capitolo della Storia d'Italia coordinata da Nino Valeri), Turin 1965: Einaudi.

- Pieropan, Gianni: 1914-1918. Storia della grande guerra sul fronte italiano, Milan 1988: Mursia.

- Rochat, Giorgio / Pozzato, Paolo / Isnenghi, Mario: 1916, la Strafexpedition. Gli altipiani vicentini nella tragedia della Grande Guerra, Udine 2003: Gaspari.

- Sema, Antonio: La Grande guerra sul fronte dell'Isonzo, Gorizia 1997: Goriziana.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence: Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf. Architect of the apocalypse, Boston 2000: Humanities Press.

- Thompson, Mark: The white war. Life and death on the Italian front, 1915-1919, London 2008: Faber and Faber.