The Eastern Front↑

In August 1914 European military thinkers still worshipped in the cult of the offensive. Most military leaders and politicians, along with the general public, assumed that any conflict would be short. New technologies like the machine gun and advances in heavy artillery, they reasoned, gave the attackers such firepower that static defenses could not hold out long. The most frequently cited example was the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871, where the Prussians’ ability to move troops rapidly to concentration points and bring heavy artillery to bear resulted in a French defeat within, essentially, six weeks. Students of the Second Boer War (1900-1902) and the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905) reached similar conclusions. The Russian General Staff, who studied their defeat at the hands of the Japanese intensely, declared in 1910 that given developments in military technology, no future war could last more than a year.[1]

When the First World War began, therefore, nearly everyone expected a war of movement, one dominated by rapid concentrations, stunning offensive breakthroughs, and sweeping envelopments. The German Schlieffen Plan, like the plans of the other Great Powers, was predicated upon these principles and thus the opening weeks of the war looked as if all expectations would be met. German armies drove rapidly toward Paris, quickly reducing the Belgian fortifications in an attempt to outflank the defenders through sheer pacing.

When the French held in the Battle of the Marne, however, the war quickly deteriorated into a stalemate. Both sides dug in, and trenches soon stretched from the English Channel to the Swiss border. For the next four years, both sides essentially remained in position; neither machine guns nor heavy artillery, neither poison gas nor armored vehicles could provide the breakthroughs everyone expected. The common story of the First World War is thus one of static warfare, with millions of men futilely charging entrenched positions or dying of disease in those positions.

This is not the only story of the First World War, however; the Eastern Front saw the realization of nearly all of the predictions about modern military conflict. For four years, the Germans, Russians, and Austro-Hungarians fought a war of movement. Rapid movement and concentration resulted in stunning “cauldron battles;” tactical and technical developments led to large-scale breakthroughs and advances (or retreats) of hundreds of miles. The only prediction that was not realized, in fact, was that the war would be decided quickly. On the Eastern Front, as on the Western, the conflict dragged on for years, with neither side truly able to deliver a knock-out blow. As Winston Churchill (1874-1965) famously noted, “In the west, the armies were too big for the land; in the east, the land was too big for the armies.”[2]

August 1914: The War of Movement↑

The Great War opened with a German invasion of Belgium, the opening gambit of the Schlieffen Plan that intended to provide Germany with its best opportunity for victory in a two-front war. Within days the five Great Powers of Europe (Great Britain, Germany, France, Austria-Hungary, and Russia) were at war. Russia, which had entered the war largely out of a sense of pan-Slavic obligation to Serbia and in the hopes of making gains on the Black Sea coast, was obligated to assist France by treaty. The tsar’s armies thus found themselves at war with both the Germans and the Austro-Hungarian Empire on a front stretching from the town of Czernowitz on the Romanian border to the city of Memel on the Baltic Sea — a distance of nearly 500 kilometers.

To defend this space, Russia deployed Europe’s largest standing army of 1 million men, which grew to some 3.5 million upon mobilization. On the northern half of the front, which Russians referred to as the Western or Northern Front, the Imperial Russian Army faced a single German Army, the eighth, left to defend the province of East Prussia. On the Russians’ Southwestern Front, the Austro-Hungarian Empire initially deployed some 500,000 men — the bulk of its forces. The Habsburgs also sent a force of about 150,000 men into Serbia, while Germany’s main effort (approximately 90 percent of its manpower) was concentrated against France.

The German plan was to level a quick, fatal blow against France and then turn against the Russian colossus, which could mobilize only slowly. Russia and France were certainly well aware of German intentions, however; and while Russia had more to gain in the Balkans, its military planners ceded to French pressure and agreed to mount an offensive in East Prussia. According to the Russian plan, known as Mobilization Schedule 19 (Variant A), two Russian armies (twenty-nine infantry divisions) would drive into East Prussia while another four armies (forty-five infantry divisions) would undertake a simultaneous offensive against Austria-Hungary. Thus while Germany sought a rapid decision in the West, Russia hoped to pound its enemies into a quick submission in the East.

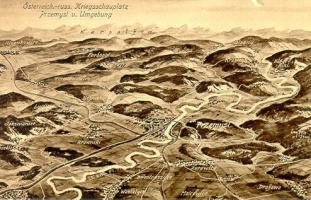

Austria-Hungary, under the command of General Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf (1852-1925), nearly played into Russia’s hands. Conrad initially focused on the campaign against Serbia and sent only three armies (twenty-seven infantry divisions, twenty-one cavalry divisions, and twenty-one third-line reserve brigades, often referred to as Staffel A) against Russia. He further assumed the Habsburg forces sent south would dispatch the Serbs quickly and then shift to the north; Conrad thus deployed his forces in a wide arc between the Vistula and Dniester rivers, hoping to take advantage of terrain and a network of fortresses centered on Przmyśl, his headquarters. Assuming the Russians would strike due south from Poland, which formed a large salient in the Central Powers’ line, Conrad designed his left wing for mobility and sent his cavalry to reconnoiter between the Vistula and Dnieper. They discovered very little.

Anticipating an Austrian drive to the east, the Russians had divided their forces into two flanking groups consisting of two armies each. The Russian Fourth and Fifth armies would strike south from Cholm and Kovel (just east of where Conrad expected them to be), while the Third and Eigth armies held positions in depth between Dubno and Proskurov on the Austrians’ eastern flank. Each side had thus aligned its strength with the other’s weakness and was essentially pushing at an open door.

The Austrians struck first, as their First Army under General Viktor Dankl (1854-1941) advanced directly into the path of General Baron Anton von Saltza's (1843-1916) Russian Fourth Army near Krasnik on 23 August. The Austrians mounted frontal charges with both infantry and cavalry that drove the Russians back, but suffered 40 to 50 percent losses in the process. Two days later, General Moritz von Auffenberg's (1852-1928) Fourth Army repeated the feat against General Pavel Plehve's (1850–1916) Russian Fifth Army at Komarow.

Austro-Hungarian attempts to follow up these victories stalled, however, and Conrad shifted some of his forces eastward in an attempt to stem the Russian advance there. General Aleksei Brusilov's (1853-1926) Eighth Army and General Nikolai Ruzki’s (1854-1918) Third Army had defeated the Austro-Hungarian Third Army under General Rudolf Brudermann (1851-1941) and the army group of General Baron Hermann Kövess von Kövessháza (1854-1924) so soundly in the Battle of the Gnila Lipa (26-30 August 1914) that the Habsburg forces retreated in disarray. Brusilov’s forces took the Austrian fortress city of Lemberg (L’viv) on 3 September.

Things quickly got worse for Conrad. The Cossack cavalry of Plehve’s Fifth Army, which he assumed had been defeated, discovered the gap left between the Austrian First and Fourth armies by the redeployment. General Nikolai Ivanov, commander of the Russian Southwestern Front, immediately sent his Fifth Army in, supported now by the newly arrived Ninth Army. Before Conrad could regroup his forces, the Russians had defeated the Austrians soundly at Rava-Ruska (3 September) and were advancing on both Przmyśl and the vital passes of the Carpathian Mountains that guarded the Hungarian plain.

The Austro-Hungarian Army never truly recovered. It had lost over 300,000 men—nearly a third of the effective force — and a good percentage of its officer corps in the offensive. The Russians laid siege to Przmyśl in late September and, had they had more resources and energy, might well have driven through the Carpathians into Hungary and knocked the Habsburg Empire out of the war. Ivanov’s forces had suffered nearly 20 percent casualties as well, however; and Nikolai Nikolaevich, Grand Duke of Russia (1856–1929), the Russian commander-in-chief, had his hands full, for the Northern Front was in disarray.

The Russians had expected nothing less than an easy victory in East Prussia. General Yakov Zhilinsky (1853-1918), commander of the Northwestern Front, deployed two large armies (each fifteen divisions) against General Maximillian von Prittwitz und Gaffron's (1848-1917) solitary and under-sized (twelve divisions) German Eighth Army, which was comprised largely of reservists and garrison troops. His plan called for General Pavel Rennenkampf's (1854-1918) First Army to drive on Königsberg in the north while General Aleksandr Samsonov's (1859-1914) Second Army would make its way around the Masurian Lakes to the south and thus trap Prittwitz’s force near Allenstein.

The separation en route of some ninety kilometers, however, meant that the two armies were not mutually supporting. They communicated only by courier, using a postbox in Warsaw. When Rennenkampf encountered the German I Corps under General Hermann François (1856-1933) at Stallupönen on 17 August, therefore, he had no idea where Samsonov’s forces were. The Germans knew exactly where the Russians were, however; not only did Prittwitz dispose of aerial reconnaissance units, he also benefited from the poor training of Russian radio operators who often broadcast messages unencrypted.

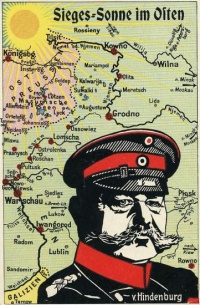

Through sheer weight of numbers, Rennenkampf managed nevertheless to inflict defeats at both Stallupönen and Gumbinnen (20 August). The Eighth Army suffered over 14,000 casualties in these battles and Prittwitz, known as “the rotund soldier,” ordered a retreat to the Vistula.[3] Shocked by the Germans’ aggressiveness and stung by the numerous casualties suffered, Rennenkampf halted rather than pursue. The German Chief of General Staff, General Helmuth von Moltke the Younger (1848-1916), annoyed at Prittwitz’s passivity, cashiered him and sent General Paul von Hindenburg (1847-1935) to replace him.

Even before Paul von Hindenburg arrived, however, Lieutenant Colonel Max Hoffmann (1869-1927) had drafted and set in motion an aggressive plan of attack. Zhilinsky, unlike Rennenkampf, had interpreted Gumbinnen as a sign of German weakness and ordered Samsonov’s Second Army to expedite its march, and cut off the retreating foe. Hoffman’s plan, which Hindenburg and his chief of staff, Quartermaster General Erich Ludendorff (1865-1937), readily adopted, called for Eighth Army to concentrate against Samsonov, leaving only a weak cavalry screen to check Rennenkampf.

Thus the Russian Second Army emerged from the Pripet Marshes on 23 August and marched directly into a trap. Four German corps (I, I Reserve, XVII, and XX) descended on the exhausted Russians and within two days (26-28 August) had turned both flanks. Three Russian corps at the center of the cauldron simply disappeared under German artillery fire. On 30 August, Samsonov committed suicide. What was left of his army made one last, futile attempt to break out, and then surrendered. The Russians lost nearly 125,000 men, along with over 500 field guns. German casualties were between 10,000 and 15,000.

The Eighth Army was soon reinforced by two corps drawn from the Western Front and wheeled north to complete the so-called “Tannenberg Maneuver.” Taking advantage of superior rail and intelligence networks, the Germans reconcentrated near the Insterburg Gap and laid a trap for Rennenkampf’s forces. Everything went according to plan, with central pinning attacks holding the Russian First Army on 7 September; then two German corps (I and XVII) crashed into its flanks on 9 September.

Rennenkampf was quicker to recognize the peril, however, and on 11 September he mounted a counter-attack that allowed his forces to avoid encirclement. Marching almost thirty kilometers a day in retreat, the First Army was back on Russian soil by 13 September. Rennenkampf had managed to inflict nearly 70,000 casualties, but suffered some 100,000 of his own. More important, the audacious and unexpected German triumphs countered the Habsburg collapse in the south and stabilized the Eastern Front for the Central Powers.

The Russians were prepared to make one last, grand attempt to win the war in 1914. Stavka, the Russian high command, aligned seven armies (east to west: Eighth, Third, Second, Fifth, Fourth, Ninth, and First) for an attack on the industrial centers of Silesia. Before the offensive truly got underway though, the Germans struck. Hindenburg shifted four corps from East Prussia (now designated as Ninth Army) over 450 miles to Częstochowa, on the Russians’ western flank, in eleven days.

The Grand Duke had prepared for this, and sent his Second and Fifth armies behind his other forces to the west, hoping to catch the Germans in a cauldron between Lodz and Lublin. On 28 September though, Hindenburg attacked between the Russian Second and Fifth armies, thus anticipating the Grand Duke’s strategy. The four Habsburg armies to the south launched supporting attacks on 1 October, forcing the remaining Russians back on Warsaw. On 10 October the Russians counter-attacked in the Battle of Ivangorod. Outnumbered sixty divisions to eighteen, Ludendorff orchestrated a masterful withdrawal to Krakow over the next two weeks. With four Russian armies still advancing, General Erich von Falkenhayn (1861-1922), the new German chief of staff, promised to send twelve new army corps to retrieve the situation.

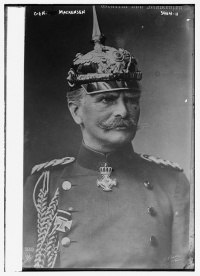

Russian incompetence made this unnecessary though, as unencrypted radio messages revealed their plans to the Germans. Hindenburg now shifted the Ninth Army 250 miles north to Torun (Thorn). Conrad, for once acting in concert with his ally, moved his Second Army from the Carpathians into the Ninth’s former position. Hindenburg and Ludendorff had thus out-flanked the Russians yet again; on 11 November, General August von Mackensen (1849-1945) led the Ninth Army up the Vistula and drove a wedge between the Russian First and Second armies in front of Lodz.

Rennenkampf’s forces suffered another 100,000 casualties, and he was relieved of command. The Second Army managed to fight its way back to the city, where it was reinforced by Plehve’s Fifth Army on 17 November. The Russian counter-attack briefly threatened to encircle the Germans, who refused to surrender and fought their way out during the course of nine freezing days. German losses totaled some 35,000, but the Russians’ were almost triple that. It seemed that no matter the circumstance, the Russians were no match for the German Army.

They handled the Austrians, on the other hand, with relative ease. While Conrad had managed to relieve Przmyśl briefly in early October, Brusilov’s Eighth Army soon retook the fortress and pushed beyond it to the Carpathians. Habsburg losses continued to mount alarmingly, especially among the officer corps, and General Svetozar Boroević von Bojna's (1849-1945) Third Army soon found itself separated from the army group of General Karl Pflanzer-Baltin (1855-1925) by some seventy miles. Only with the aid of the German 47th Reserve Infantry Division and the onset of severe weather were the Austro-Hungarian forces able to hold the Russians out of Hungary at the Battle of Limanova-Lapanow (1-17 December).

1915: Breakthrough and Retreat↑

As 1914 came to a close, the war looked very much like a stalemate. While trench warfare dominated the Western Front, the Eastern Front — where geography rendered such a development unlikely — offered the best chance to avoid that outcome, and the German-Austrian cooperation at Limanov-Lapanow suggested how it might be done. Convinced by Hindenburg and Ludendorff of the possibilities, Wilhelm II, German Emperor (1859-1941) intervened for once in the disputes among his commanders and ordered that the major military effort for 1915 take place in the East. Falkenhayn accordingly strengthened German forces there with a new army (Tenth) and authorized the formation of a new, mixed Austrian-German force, the Südarmee, to cooperate with Habsburg efforts in Galicia.

Conrad, however, guarded Habsburg sovereignty (and his own) jealously. Rumors of a unified command, headed by Hindenburg, had been swirling all autumn; Hindenburg’s elevation to Commander-in-Chief of the Eastern Front on 2 November did nothing to alleviate Conrad’s insecurity. Although he wanted German help to offset Russian numbers, Conrad found both Falkenhayn and Hindenburg distasteful, and their methods appalled him.

To prevent “terrorism,” the German commanders on the Eastern Front instituted capital punishment for any “unjustified war activity” that might give the enemy an advantage. Hindenburg also informed the Austrians that he intended to burn down two villages in Russian Poland for every village the Russians burned in East Prussia. During the chaotic retreat of September 1914, Cossacks and the Russian rearguard had systematically destroyed entire villages and executed several Poles for suspected partisan activities.[4] For reasons both political and personal, this approach to war was beyond Conrad.

The finer points of modern warfare also eluded the Habsburg commander. Eschewing cooperation, or even direct communication with the Germans, Conrad planned major offensives on the Galician and Carpathian fronts for early 1915. His intent was to relieve the Russian threat to Hungary, above all by recovering Przmyśl, currently invested by General Andrei Selivanov's (1847-1917) Russian Eleventh Army. Pflanzer-Baltin’s army group would carry out a feint toward Czernowitz to the east, while Boroevic’s Third Army would combine with the Südarmee for a frontal assault to relieve the fortress.

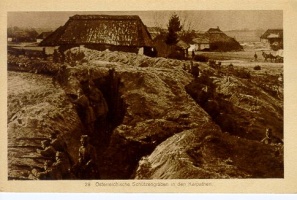

Launched on 23 January, the offensive was a disaster. Snow and dense fog made operations in the Carpathians all but impossible. “Hundreds freeze to death daily,” an officer in Third Army wrote; “every wounded soldier who cannot get himself back to the lines is irrevocably sentenced to death. Riding is impossible. Entire lines of riflemen surrender in tears to escape the pain.”[5] Although Pflanzer-Baltin captured Czernowitz, Conrad called off the offensive on 8 February, his forces in the Carpathians having suffered over 100,000 casualties. A second attempt at the end of the month fared no better; the Austrian armies lost another 45,000 men in only ten days, including the last of their trained officers. Przmyśl fell on 23 March, and soon the Russians were again at the passes to Hungary.

Hindenburg had tried to support the Habsburg offensives with strikes against the Russians in the north, where Nikolai Nikolaevich had formed a new army (Twelfth) with an eye toward a second invasion of East Prussia. In late January, the German Ninth Army made a feint toward Warsaw, using poison gas as a weapon (unsuccessfully) for the first time in the conflict. Hindenburg then pre-empted the Russian offensive, sending his Eighth Army against the left flank of the Russian Tenth on 7 February to open the second (Winter) Battle of Masurian Lakes. The German Tenth Army struck the Russians’ right flank the following day, driving them back past Stallupönen to Luck. The Germans nearly managed to surround the entire Russian Army on 21 February and repeat First Masurian Lakes. A courageous counter-attack by the Russian XX Corps allowed the other three corps to escape, however, and the Russian Twel advanced to halt the German drive the next day.

Falkenhayn and Conrad now realized that joint operations were the only reasonable way forward. The Germans had had to send a rescue force, the Beskiden Korps, to keep the Russians out of Hungary, and the Austrians were simply running out of manpower. Nearly one half of the original strength of the Habsburg armies had disappeared—missing, dead, or wounded—in less than a year; most of the cavalry was dismounted for the remainder of the conflict for lack of officers and horses. The Austrians and Hungarians tightened and expanded the draft, but Conrad advised Hindenburg in May that Habsburg divisions should be counted as no more than brigades.

Determined that the war could now be won in the east, Falkenhayn formed a new army (Eleventh) under Mackensen using new recruits and units gained from a re-organization on the Western Front. Overriding Hindenburg’s demands for another attack in the north, Falkenhayn adopted Conrad’s plan for an offensive in the south. Mackensen’s force would be inserted between Joseph Ferdinand, Archduke of Austria's (1872-1942) Fourth Army at Tarnow and Boroevic’s Third at Gorlice, giving the Central Powers a numerical advantage in guns (1,500 v. 700) and troops (357,000 v. 219,000) along that stretch. For the first time, Austro-Hungarian and German units would operate under a unified command. The Beskiden Korps remained as part of the Habsburg Third while the Austrian VI Corps was part of the German Eleventh Army; the German Army Group Woyrsch was also placed under Habsburg command.

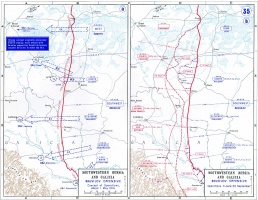

On 2 May, following a short (four-hour) heavy artillery barrage, the Austro-Hungarian Fourth stormed Tarnow and occupied the town. The Russians, lacking heavy guns and in the midst of a critical shortage of shell, retreated along a forty-kilometer front to a depth of some 100 kilometers over the next two weeks. This left the flank of their forces in the Carpathians exposed, compelling them to withdraw as well. Stavka demanded the troops hold their ground, but the heavy artillery of Mackensen’s forces was simply overwhelming. “Trees break like matches,” a German officer wrote of one barrage, “huge trunks are hurled through the air, the stone walls of houses cave in, fountains of earth rise from the ground.”[6] The Central Powers retook Przmyśl on 3 June and entered Lemberg (L’viv) on 22 June, crossing the Dniester five days later.

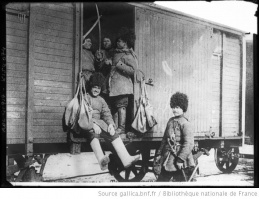

As the inadequate Russian road and rail nets finally slowed Mackensen’s advance, Hindenburg launched a second offensive against Russian Poland on 13 July using yet another new army (Twelfth). Nikolai Nikolaevich abandoned the Russian fortresses there, stripping them of what heavy artillery his forces could carry in the retreat. By mid-August, the Germans were in possession of Lublin, Cholm, Ivangorod, and Warsaw. The offensive finally ground to a halt in Vilna on 19 September, the autumn rains having rendered the roads impassable. “Exertions, privations, very heavy knapsack, neck and shoulder pain from the rifle and long, difficult marches,” one German soldier recalled, “extremely tired feet and body. Bad roads—either uneven asphalt or deep sand—and always the uneven fields, marching up and down deep furrows. Often in double-time, and usually no water or at best stinking water, no bread for days on end. [...] Nothing but freezing and freezing, and back pains.”[7]

In the course of four months the Russians had retreated over 300 miles and lost more than 1,000,000 men (killed, wounded, and captured). Yet Russia remained unbroken. Both Ivanov in the south and Nikolai Nikolaevich in the north had managed to avoid the encirclements Mackensen tried to create and kept their armies intact. Russian soldiers joked that they would simply let the advance continue until the enemy wore himself out: “There will only be one German and one Austrian left,” they said. “We will kill the German, and the Austrian will gladly surrender.” Nicholas II, Emperor of Russia (1868-1918), for once decisive, refused to consider even negotiations for peace. Invoking the memory of the Patriotic War against Napoleon I, Emperor of the French (1769-1821) in 1812, the tsar vowed to drive the invaders from Russian soil. To facilitate this, he relieved the Grand Duke of his duties as commander-in-chief and assumed them himself. “With firm faith in the clemency of God, with unshakeable assurance of final victory,” he wrote, “we shall fulfil our sacred duty to defend our country to the last. We will not dishonor the Russian land.”[8]

The tremendous success of the Gorlice–Tarnów Offensive eliminated the Polish salient and stabilized the Eastern Front once again. Hindenburg installed a military government in Poland, and used gangs of prisoners of war (POWs) to exploit the material resources of the region. The army’s railway directorate took control of not only transport but also press and education, seeking to turn Poland into a German colony. The failure to bring Russia to the table, however, led Falkenhayn to turn his gaze back to the Western Front, where he was certain the tactics of Gorlice would bring success, particularly at Verdun. This provided Conrad, chafing at the clearly subordinate role Habsburg troops and commanders had played, with an opportunity to restore both the confidence and prestige of the Austro-Hungarian armies.

Although deprived of many of his best units by the Italian entry into the war in May 1915, which opened a third front against Austria-Hungary, Conrad envisioned a grand “Gold-and-Black Offensive” (those being the Habsburg colors) he believed would drive Russia from the war. By drawing on the draft cohort of 1897 and incorporating the last of the Austro-Hungarian reservists, Conrad put together a force of fourteen divisions. The plan was to launch Third Army and Army Group Roth as two wings in the direction of Kiev, encircle, and then annihilate the Russian Eighth Army.

The Russians again managed a skillful retreat, however, and the Habsburg commanders — General Paul Puhallo von Brlog (1856-1926) and General Josef von Roth (1859-1927) — not only failed to coordinate their attacks, but wasted their troops in full frontal assaults reminiscent of those that had been so costly in August 1914. Early victories at Rovno and Lutsk (29 August) thus turned into defeats as the Russian Eighth counter-attacked the under-strength Habsburg units. By the time the rains mercifully halted operations, the Austro-Hungarians had suffered another 231,000 casualties—almost half of them taken prisoner. Only another German intervention prevented worse defeats. Where Hindenburg and Ludendorff believed that the events of 1915 had rendered Russia incapable of launching further offensives, in reality it was the military power of Austria-Hungary that was at an end.

1916: Russia Revitalized, Austria Exhausted↑

The Eastern Front was quiet in the winter of 1915-1916. Falkenhayn had shifted his attention to the Western Front, and Conrad was concentrating on Italy — while consolidating a defensive position in the East. Although a member of the Triple Alliance (Central Powers), Italy had refused to enter the war in August 1914 on grounds that Austria-Hungary and Germany had not met their obligation to keep Italy informed. As if that were not treason enough in Conrad’s eyes, the Italians had then demanded Austrian territory (especially southern Tyrol) as the price of participation. When the Habsburgs offered only the Trentino, Italy joined the Triple Entente via the Treaty of London (26 April), which promised to deliver all the Habsburg lands Italy desired. Conrad, having long suspected Italy of harboring such ambitions, now declared it “the true enemy.” He shifted eight of his best and most experienced divisions, including the Eighth Mountain Infantry and all of his mountain artillery, from Galicia on the Eastern Front to face Italy. Believing the Russians’ offensive capability at an end, the Austro-Hungarians built permanent, fortified defensive positions in Galicia and manned them with raw recruits.

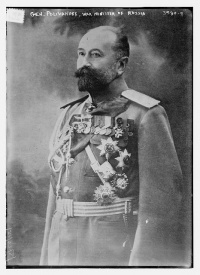

Russia was far from finished though. Vladimir Sukhomlinov (1848-1926), the Russian Minister of War from 1909 to June 1915, had been relieved once the scope of the shortages of war material (along with his attempts to cover up rather than address them) became fully known. His replacement, Aleksei Polivanov (1855-1920), immediately set about rejuvenating the Russian Army.

As a relatively liberal officer, Polivanov sought greater public involvement in the war effort, hoping to rouse Russian patriotism. In an earlier stint as Assistant Minister of War (1906-1912), he had worked with Duma (parliament) representatives to modernize Russia’s artillery; now he re-established these contacts and brought in several leaders of Russian industry to form Special Councils to assist the ministry in procuring adequate materiel. Polivanov also took steps to improve communications, focusing on training operators, and emphasized physical fitness and combat training for new recruits. Perhaps most important though, Polivanov opened the junior officer ranks to those who displayed merit, and established an extensive and effective network for the training of Non-Commissioned Officers (NCOs) and junior officers. In all of these ways, Polivanov brought the Russian Army up to European standards of the day, or very nearly so.

The change was not immediately evident, however, as Nicholas sent “the Polivantsy” into action before the program was anywhere near complete. Responding to French pleas for relief of the pressure at Verdun, the tsar ordered an attack against the Germans in the vicinity of Lake Naroch (Narocz) in March 1916. Stavka selected Lake Naroch because the Russians deployed some 350,000 men there against only 75,000 Germans, but little thought was put into the actual operation. The Russian First and Second armies were to attack on either side of the lake with the aim of encircling the German Tenth Army — a maneuver that would supposedly force Falkenhayn to detach units from the Western Front and prevent a breakthrough.

The opening bombardment lasted two days and was of no use whatsoever. Russian artillery units had not registered their guns, so most of the shells fell harmlessly. After some initial Russian gains between 18-20 March, the area was hit by an unseasonable thaw. The roads and fields turned to mud, and the Russian attackers bunched up and became easy targets for embedded German machine gun units. Using highly accurate artillery fire directed by prior aerial reconnaissance, the Germans effectively silenced the Russian guns. An innovation, the creeping barrage, then allowed the Germans to counter-attack with lethal efficiency. After suffering some 70,000 casualties (against only 30,000 for the Germans), the Russians returned to their lines having failed to realize their objectives.

When the Italians, faced with a possible breakthrough by Austro-Hungarian troops in the Trentino in May 1915, called upon the Russians to attack in Galicia and relieve the pressure on them, virtually every Russian commander declined. General Aleksei Brusilov, newly appointed as commander of the Southwestern Front, was the exception. He offered to launch an offensive along his entire 300-mile front, stretching from Kovel in the north to Czernowitz on the Romanian border, using four armies (north to south: Eighth, Eleventh, Seventh, and Ninth). The Austro-Hungarians were in the process of finishing deep, hardened defensive positions along the front and deployed almost equal manpower and firepower, but Brusilov had a plan.

Lacking the firepower to blow holes in the enemy line, as Mackensen had done at Gorlice, Brusilov adapted tactics developed on the Western Front to the broader scale of the East. He brought forward all reserves and put them to work digging out large holding areas fronted by huge ramparts that would hinder enemy observation. They then dug communications trenches to allow the reserves to shift behind the lines, and finally sapped to within sixty meters of the Austrian front lines. When the soldiers were not digging, they practiced assaulting reconstructions of the Austrian positions derived from aerial reconnaissance photos. Army commanders also used the photographs to determine their attack points, which were to be on fronts fifteen to twenty kilometers wide. Brusilov further instructed his commanders to paint false trenches on the ground and construct wooden “batteries” that would deceive enemy aerial observers and obscure the point of attack.

The Austrians were well aware an attack was in the works, and believed their defenses were impregnable; however, Brusilov’s new tactics caught them by surprise. The preparatory barrage of 4 May lasted only a few hours and focused on the Habsburg artillery: no infantry attack followed. A second, short artillery fusillade around noon blew small holes in the Austrian front lines but again, there was no follow-up attack. Not until the afternoon did small groups of Russian infantry emerge from their trenches on the Austrians’ doorstep and launch the offensive.

Near Lutsk and Brody, the effect was minimal; Südarmee and the Austrian Fourth reported little damage. At Sapanow, however, the story was different. The focused Russian barrage had shredded the defensive obstacles of the Habsburg Second Army and disrupted communications between front and rear. Curtain fire pinned many units in their bunkers. When thirteen armored vehicles appeared out of the smoke and dust, several units in the front line broke and fled. Russian troops moved quickly into the gap and began expanding the attack horizontally along the front trench; a second wave soon followed, moving to the next trench and repeating the process. Machine gun units followed to secure the breakthrough, and then the cavalry pushed through the gap.

Similar breaches in the line of the Austrian First Army, on the Ikwanie River, and Seventh Army, along the Dniester, caused panic among the Habsburg commanders. The best Austro-Hungarian units had been diverted to Italy for the Trentino Offensive, and they feared that any setback might damage the mettle of their untested units. Disobeying directives from headquarters, the army commanders therefore sent their reserves forward piecemeal to plug each small gap that appeared. This might have worked against the traditional Russian attack, in which a broad, deep column attempted to push through the line; however, against the broadening waves sent forward by Brusilov it meant that the reserves were isolated and often destroyed in detail. The Austrian Seventh, which was perhaps most guilty in this regard, lost its entire position in the course of two days and spent the night of 5 June desperately re-entrenching in an open field five kilometers behind the lines.

The broad spaces of the Eastern Front stretched front lines thin and intensified the effect of the multiple Russian breakthroughs. The retreat of the left wing of the Austrian First exposed the right flank of the Austrian Fourth, and drew off the reserve. This left the Fourth Army unable to contain the Russian attacks, and by 10 June General Mikhail Kaledin’s (1861-1918) Eighth Army had advanced beyond the Styr River and taken Lutsk, an advance of nearly seventy-five kilometers along a front three times as long. General Vladimir Sakharov's (1853–1920) Eleventh Army thus was approaching Brody, while General Platon Lechitski’s (1856-1923) Ninth Army had crossed the Dniester, over-run Czernowitz, and pushed the Austrians back to the Carpathians in the south. With both flanks now open the mixed Austro-German Südarmee, which had held firm in the center of the Southwestern Front along the Strypa River, was also forced to withdraw.

The speed and depth of the Russian breakthrough, however, demonstrated the limits of Brusilov’s approach. Lacking adequate reserves and a well-developed supply and transportation network, his armies could pursue the fleeing Austrians only slowly. The extensive Russian offensives planned for the Northern Front failed to materialize, moreover, as the Russian commander lost his nerve. The more mobile German Army thus had time and reinforcements to stem the attack. Falkenhayn sent four divisions to aid the Austrians on 14 June; four additional divisions arrived from the Western Front a month later, along with a complement of German artillery. German units counter-attacked the Russians and established new defensive positions while their aircraft drove the Russians from the skies, denying them the benefits of reconnaissance. Brusilov’s tactics — which relied on extensive preparation — now faltered.

Reinforced by the Russian Guards Army and units drawn from the Northern Front in mid-July, Brusilov sought to extend his gains while the chance still remained. Without adequate intelligence, and lacking heavy artillery and the time for extensive sapping though, his commanders fell back on the tactics of 1914 — and met with similar results. Initial success at Brody and at Chartorysk stalled as better-trained German soldiers moved into the lines and German officers assumed command of Austro-Hungarian units. The Guards Army found itself pinned down by German artillery behind the Stochod River and lost more than 30,000 men between 27 July and 4 August while attempting to take the important rail junction of Kowel. The huge cavalry contingent of Letschitski’s Third Army milled about uselessly, awaiting another breakthrough. Discouraged and lacking both resources and a plan, the remaining Russian commanders allowed the offensive to simply peter out in mid-August.

The Brusilov Offensive had regained for Russia nearly all the territory lost on the Southwestern Front during 1915 and virtually ended the Habsburg military effort. The failure of General Aleksei Evert (1857-1926) to attack simultaneously in the north, however, meant the Russians gained no ground there while the Germans were free to transfer reserves south and halt the offensive. The Austro-Hungarians had lost more than 9,000 officers and over 700,000 men killed, wounded, or taken prisoner— almost 70 percent of the effective fighting force of May 1915. Conrad had been forced to withdraw four divisions from Italy to man the lines in Galicia. He was promoted to Field Marshal in November 1916, but it was a face-saving measure as Hindenburg and Ludendorff formally assumed command over the entire Eastern Front. German soldiers filled out Austro-Hungarian units, and Habsburg soldiers donned German field grey uniforms and spiked helmets. Even the sole army nominally still commanded by an Austrian (Army Group Archduke Karl) was in reality controlled by its German chief of staff, General Hans von Seeckt (1866-1936). Perhaps the final, unsustainable blow, however, was the death of Francis Joseph I, Emperor of Austria (1830-1916) on 21 November 1916; thereafter, the Habsburg Empire simply unraveled.

The cost of Russian success, however, had been tremendous and left the Russian Empire hardly in better shape. Despite Brusilov’s innovations, the Russian Army suffered nearly 2 million casualties in the summer of 1916, with half of them killed. Any hope of reinforcement was dashed when Romania entered the war (27 August) and suffered a rapid and disastrous defeat; Russia sent twenty-seven divisions to stem the Central Powers’ advance there and stabilize the additional 320 miles of front. The demoralizing experience in Romania, along with the massive losses in July and August, finally broke the Imperial Russian Army. Small anti-war incidents occurred in some corps as early as 1 October, and more than a dozen regiments mutinied in December 1916. “Take us and have us shot,” one company telegraphed the tsar, “but we just are not going to fight any more.”[9]

1917: Russia’s Dying Gasp↑

The sheer exhaustion of two out of three major combatants rendered the Eastern Front a military sideshow in 1917, as already indicated by Hindenburg and Ludendorff’s transfer to headquarters on the Western Front in August 1916. Politically, and strategically, however, the Eastern Front remained important simply because its continued existence prevented the Germans from transferring large numbers of troops to the Western Front.

It looked briefly as if Russia might rejuvenate itself once again. In February and March, demonstrations in Petrograd (as St. Petersburg had become known, to avoid Germanic connotations) shook the foundations of the tsarist regime. Cossacks, previously staunch and feared defenders of autocracy, sided with the demonstrators, as did many military units—who preferred the risk of imprisonment over going to the front. Disturbed, Russian chief of staff General Mikhail Alekseyev (1857-1918) circulated a memo to his army commanders to assess their support for the tsar; he was forced to tell Nicholas that the military believed he should resign. When the tsar did abdicate, on 15 March (new style), many of Russia’s generals and leading politicians hoped that the country would rally behind its new, quasi-democratic government and drive the invader from the country, as the French had in 1792.

Most also insisted on maintaining military discipline — with some easing of the draconian punishments so infamous in the Russian Army, but even this clashed with the revolutionary sentiment of the day. The Petrograd Soviet of Workers, Soldiers, and Sailors—the leading revolutionary political body in the city, though technically it shared power with the Duma—issued both “Order Number One” and “The Declaration of the Rights of the Soldier.” These called for equality among the soldiers, with no insignia of rank to be used, an end to saluting, and unit votes on any proposed military action, among other things. Many commanders resigned, recognizing that it was impossible to conduct affairs in this manner.

Alexander Kerensky (1881-1970), the revolutionary minister of war, believed otherwise; he was convinced that, stirred by patriotism and revolutionary fervor, the Russian people would rise up and smite the Germans. Maria Bochkareva (1889-1920), who had been serving in the Russian Army since 1915 with the special permission of the tsar, took up this idea and, with Kerensky’s blessing, formed the Women’s Battalion of Death. She intended it to both set an example for women (many did sign up, and other women’s battalions of death soon followed) and shame Russia’s men into fighting. Bochkareva led her unit into combat on the Southwestern Front, where it served as part of the Russian Eleventh.

Few soldiers appreciated Bochkareva’s example; the Kerensky Offensive (also known as the Second Brusilov Offensive, because Brusilov was now chief of staff) launched on 1 July looked no different than most other Russian offensives of the First World War. Brusilov sent three armies (north to south: Eleventh, Seventh, and Eighth) to capture the oil fields at Drohobycz and then drive on Lemberg (L’viv). The opening attacks, carried out on a 130-kilometer front, forced the Austrians back up to forty kilometers—though “forced” may be over-stating the case; the Austrian troops were even more demoralized than the Russians, and many simply threw down their arms and fled. When German reinforcements arrived, the Russians broke in turn and returned to their own lines. Bochkareva’s unit was decimated, probably by friendly fire. Many of her surviving comrades were later lynched by male soldiers, and Bochkareva narrowly escaped with her life. Dismayed, Bochkareva soon left and went to the United States, where she met President Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924) and dictated her memoirs.

On 19 July, the Germans counter-attacked toward Tarnopol; the Russian formations opposing them simply vanished. The Central Powers advanced twelve kilometers on the first day of the offensive and captured Tarnopol on 25 July. By early August, the Russians had evacuated both Galicia and the Bukovina, surrendering all of the gains of 1916. In the chaotic flight to the rear, soldiers shot their officers and simply began walking home. For all intents and purposes, Russia disposed of no organized military force south of the Pripet Marshes. The counter-offensive nonetheless ground to a halt at the Galician border. Austria-Hungary had no further reserves to dedicate to the attack, and the Germans needed every available man on the Western Front. For the moment, Russia was spared.

Ludendorff, however, was determined to drive Russia from the war and free up some of the eighty German battalions that remained on the Eastern Front. Shifting his artillery north, Ludendorff ordered an attack on Riga; if that city fell, he reasoned, the road to Petrograd would be open and Russia would be forced to conclude peace. The Germans opened the offensive on 1 September with a massive bombardment of gas and high explosive shell orchestrated by Lieutenant Colonel Georg Bruchmüller (1863-1948), perhaps the conflict’s pre-eminent artillerist. General Oskar von Hutier's (1857-1934) Eighth Army took the city two days later; anticipating the attack, General Vladislav Klembovsky (1860-1921) had withdrawn his Twelfth Army several weeks earlier, leaving only a skeleton force to defend Riga.

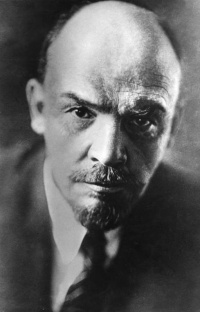

Ludendorff thus failed to achieve his strategic objective of forcing a Russian surrender directly. The fall of Riga, however, triggered a dramatic power struggle within Russia. General Lavr Kornilov (1870-1918), who had replaced Brusilov as chief of staff in August, demanded that Kerensky (by this time the head of the increasingly weak Provisional Government) transfer power to him in order to deflect the impending crisis. Kerensky refused, and Kornilov began moving his army toward Petrograd. Feeling betrayed by the army, Kerensky turned for support to the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin (1870-1924), which only recently had been suppressed for an attempted coup of its own, the so-called July Days.

Bolshevik agitators and sympathetic railway workers combined to halt Kornilov’s drive on the capitol; Kornilov was arrested on 12 September, but the days of the Kerensky government were numbered. The Bolsheviks, with Leon Trotsky's (1879-1940) Red Guard now armed and enjoying a reputation as the defenders of revolutionary democracy, staged a nearly bloodless coup on the night of 6-7 November. Kerensky fled the capital.

Although the Bolsheviks were few in number (even Trotsky had only recently joined the party officially), many Russians supported the party for its policies of “Peace, Bread, and Land.” Lenin and Trotsky accordingly attempted to withdraw Russia from the war promptly. Lenin suggested a truce on all fronts to be followed by negotiations, which the British, French, and Americans rejected. Germany, on the other hand, was eager to settle the war and opened unilateral talks with the new Bolshevik government on 3 December at Brest-Litovsk.

They agreed on an armistice, which took effect on 17 December, but little else. Trotsky somewhat naively expected the Germans to negotiate on the basis of no annexations and no indemnities; the Germans instead put forth harsh territorial demands. When Trotsky first stalled and then left the talks, declaring a policy of “no peace and no war,” the Germans took action. After signing a separate peace treaty with Ukraine, Germany marched its armies into the areas vacated by the deserted Russian soldiers, including the Baltics.

The Impact of the Eastern Front↑

This unopposed advance was the last action of World War I, the Great War, on the Eastern Front. On 3 March 1918, the Bolshevik government signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, ceding control of Ukraine, Galicia, Finland, the Baltic States, and the Caucasus. Violence continued almost unabated for the next four years, however, as the various states and populations fought for power. Russia devolved into civil war, with parties of all stripes (including socialist) trying to moderate or overthrow the Bolshevik regime. A three-way struggle evolved in the Ukraine, with Russians fighting Ukrainian nationalists, and anarchists under Nestor Makhno (1888-1934) fighting both.

The Allies perpetuated the chaos and violence of the Eastern Front as well, as they refused to accept the Bolshevik withdrawal. The United States sent 5,000 soldiers to Arkhangelsk (and a further 8,000 to Siberia), while the British sent a Royal Navy Squadron to the Baltic along with a small British Empire land force. Italy, Romania, Greece, and Serbia also provided small troop contingents, while France supplied funding for Russian forces fighting the Bolsheviks. The Allies also hoped to deny, at least, the vast resources of Ukraine and central Russia to the Germans. Thus while Hindenburg and Ludendorff transferred forty divisions to the Western Front they also, significantly, left almost as many to manage the occupation and exploit the resources of the areas gained.

The war on the Eastern Front thus continued to influence developments in the West to a degree that, even today remains generally unrecognized. It may be, as scholars generally agree, that the war was and only could have been decided in the West; however, without the East that decision might have been very different. The sheer weight and surprising ability of the Russian Army to sustain military operations and inflict damage upon the Central Powers siphoned valuable resources from the German war effort. In January 1916, near the height of the German commitment to the Eastern Front, there were fifty-five German infantry divisions and nine German cavalry divisions operating against Russia. As late as November 1918, at the close of the war, there were still twenty-seven German infantry divisions deployed in the East. More than 1.5 million German soldiers were killed, wounded, or captured on the Eastern Front.

While those numbers represent roughly only a quarter of the German forces deployed and the same proportion of casualties, they are not insignificant. The timing and nature of German deployments was also critical. The Brusilov Offensive, for instance, drew as many as eight German divisions from the Western Front that might well have been used at Verdun. The occupation of Ukraine tied down thirty or forty divisions that might have enabled the Spring (Ludendorff) Offensives of 1918 to find success. The Gorlice-Tarnów Offensive, on the other hand, provided materials and foodstuffs without which Germany might have succumbed to the Allied blockade. All of these aspects, along with the development of the creeping barrage, the experiments with poison gas, and many others, may not have been decisive for the conflict as a whole, but they certainly contributed to the decision.

Timothy C. Dowling, Virigina Military Institute

Section Editors: Michael Neiberg; Sophie De Schaepdrijver

Notes

- ↑ Rielage, Dale C.: Russian Supply Efforts in America during the First World War. Jefferson 2002, p. 131 n.6; Herwig, Holger H.: The First World War: Germany and Austria-Hungary, 1914-1918. London 1997, p. 64.

- ↑ Churchill, Winston: The Unknown War: The Eastern Front. New York 1931, p. 76.

- ↑ Herwig, Holger H. and Heyman, Neil M. (eds.): Biographical Dictionary of World War I. London 1982, p. 25.

- ↑ Herwig, First World War, pp. 127-128.

- ↑ Österreichischer Bundesministerium für Landesverteidigung/Österreichisches Kriegsarchiv (eds.): Österreich-Ungarns Letzter Krieg, 1914-1918. Vienna 1933, volume 2, p. 142.

- ↑ Von François, Hermann: Gorlice 1915. Der Karpathendurchbruch und die Befreiung von Galizien. Leipzig 1922, p. 42.

- ↑ Herwig, First World War, p. 144.

- ↑ Knox, Alfred: With the Russian Army, 1914-1917. New York 1971, p. 330.

- ↑ Lincoln, W. Bruce: Passage through Armageddon. The Russians in War and Revolution, 1914-1918. New York 1986, p. 260.

Selected Bibliography

- DiNardo, Richard L.: Breakthrough. The Gorlice-Tarnów campaign, 1915, Santa Barbara 2010: Praeger.

- Dowling, Timothy C.: The Brusilov offensive, Bloomington 2008: Indiana University Press.

- Gatrell, Peter: Russia's First World War. A social and economic history, Harlow 2005: Pearson/Longman.

- Gildhorn, Fred: Vier Jahre an der Ostfront. Offensive, Zurich 1935: Oprecht & Helbling A.G..

- Herwig, Holger H.: The First World War. Germany and Austria-Hungary, 1914-1918, London; New York 1997: Arnold; St. Martin's Press.

- Knox, Alfred William Fortescue: With the Russian army, 1914-1917, volume 1-2, New York 1971: Arno Press.

- Lee, John: The warlords. Hindenburg and Ludendorff, London 2005: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- Lincoln, W. Bruce: Passage through Armageddon. The Russians in war and revolution, 1914-1918, New York 1986: Simon and Schuster.

- Liulevicius, Vejas Gabriel: War land on the Eastern front. Culture, national identity and German occupation in World War I, Cambridge 2000: Cambridge University Press.

- Ludendorff, Erich: My war memories, 1914-1918, London 1919: Hutchinson & Co.

- Nebelin, Manfred: Ludendorff. Diktator im Ersten Weltkrieg, Munich 2010: Siedler.

- Rauchensteiner, Manfried: Der Tod des Doppeladlers. Österreich-Ungarn und der Erste Weltkrieg, Graz 1993: Styria Verlag.

- Rothenberg, Gunther E.: The army of Francis Joseph, West Lafayette 1976: Purdue University Press.

- Rutherford, Ward: The Tsar's war, 1914-1917. The story of the Imperial Russian army in the First World War, Cambridge 1992: I. Faulkner.

- Sanborn, Joshua A.: Drafting the Russian nation. Military conscription, total war, and mass politics, 1905-1925, DeKalb 2003: Northern Illinois University Press.

- Showalter, Dennis: Tannenberg. Clash of empires, Dulles 2004: Potomac Books Inc..

- Sondhaus, Lawrence: Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf. Architect of the apocalypse, Boston 2000: Humanities Press.

- Stoff, Laurie: They fought for the motherland. Russia's women soldiers in World War I and the revolution, Lawrence 2006: University Press of Kansas.

- Stone, Norman: The Eastern front, 1914-1917, London; Sydney; Toronto 1975: Hodder and Stoughton.

- Torrey, Glenn E.: The Romanian battlefront in World War I, Lawrence 2011: University Press of Kansas.