Introduction↑

From the very first weeks of combat onwards, the First World War unleashed a formerly unknown dimension of mass killing and produced unprecedented forms of physical injuries, illnesses and nervous disorders in all belligerent armies. From the viewpoint of the military, these innumerable casualties created a highly precarious situation. As a soldier’s health was increasingly considered to be a crucial factor in combat, physical and psychological health were viewed as powerful additional weapons on the battlefield, capable of becoming the decisive factor to either eventually defeat, or, at the very least, hold out for longer than the enemy.[1] From the authorities’ perspective, this came down to each and every soldier, as no potential fighting capacity could be wasted or allowed to lie fallow. Therefore, officials made every effort to create effective medical treatment schemes in order to send patients back to the front as soon as possible – ideally “cured” and “fit for duty.”

This rehabilitation programme was to take place in military hospitals. In often provisional field hospitals close to the front and even more so in well-equipped reserve hospitals back home, patients spent weeks, months and, in some cases, up to several years, recovering – depending on their injury or illness. In this way, the temporary hospitalisation of soldiers became a mass phenomenon of World War I. It affected and shaped the lives of millions of injured soldiers in all belligerent armies. German writer Erich Maria Remarque (1898-1970) famously stated in his 1929 novel All Quiet on the Western Front, “A hospital alone shows what war is,” referring to the enormous amount of suffering and loss blatantly obvious to all who visited, stayed at or worked in the war hospitals.[2] At the same time, hospitals highlighted other aspects of the Great War as well, as they were also places in which propaganda could (be) spread, intimacy and comradeship could blossom and flourish, conflicts between military and civilian actors could be carried out and family reunions took place. In this manner, hospitals displayed many different, and often ambivalent or contradictory, aspects of the war. This article will provide a transnational overview of the different types of hospitals that existed during the First World War. It will mainly concentrate on hospitals from Western Front countries. A special focus will be on hospitals on the home fronts and on the experiences of the patients treated in them, paying particular attention to war hospitals in Germany as, up until recently, this area has been rather neglected by scholars.[3]

War Zone Hospitals↑

Wounded and sick servicemen could seek treatment, safety and rest at military hospitals. These facilities did not operate independently. They always belonged to bigger national hospital systems that were responsible for covering the area from right behind the lines to the home fronts whilst remaining in communication with one another. Hospitals were commanded and supervised by a complex network of military institutions. In Britain, the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) was responsible for the organisation of hospital care. In France it was the Service de Santé des Armées (SSA).[4] In Germany, the administration of medical services was subdivided into two areas: the field medical service (Feldsanitätswesen) on the one hand and the domestic medical service (Heimatsanitätswesen) on the other.[5] The latter was commanded by the four medical bureaus of the Prussian, Bavarian, Saxonian and Wurttemberg war ministries as well as regional medical offices.[6] Five types of military hospitals existed during the war: firstly, field hospitals (or Casualty Clearing Stations (CCSs) in the British army) close to the front lines, secondly, base hospitals in the rear, thirdly, home front hospitals, fourthly, hospitals in means of transportation (hospital trains and hospital ships) and finally, fifthly, prisoner-of-war hospitals. Additionally, naval hospitals were established for the treatment of wounded and sick marines. They were administered separately from army hospitals.[7]

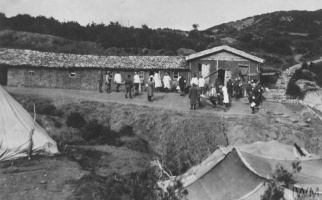

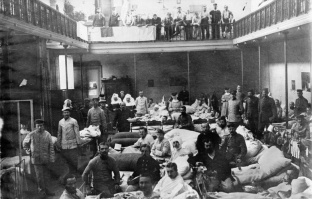

Although military hospitals of all belligerent armies shared some common features, there was no such thing as a typical First World War field or base hospital. Instead, the medical conditions and atmosphere of these temporary facilities varied considerably, depending on geographical location, the current war phase and the training and number of the medical staff on site. Hospitals on the Western Front tended to be more modern than those on the Eastern Front. Therefore, injured soldiers, doctors, and nurses were greatly affected by the type of hospital or specific facility they were sent to for recovery or work.[8] At the same time, all hospitals shared a common goal – that of treating and discharging patients as quickly as possible. Field hospitals were mobile and flexible facilities, tasked with moving along with the military unit during mobile warfare. During trench warfare, they became more stable and their medical infrastructures began to develop and improve. Field hospitals were often established provisionally on farms or in monasteries, churches, castles or other large, readily available buildings. Alternatively, they were set up in tents.[9] In the British army, CCSs were the main medical facilities behind the front lines. Hence, they were equivalent to field hospitals.[10] After periods of intense fighting these hospitals were often overcrowded with severe cases transferred from aid posts and clearing stations and treatment conditions deteriorated significantly. It is not surprising that the common image of the military hospital as a “butcher’s kitchen”[11] can be traced back to the experiences soldiers had in these types of improvised and overcrowded field hospitals. The medical strategy drawn up by the military advised doctors to keep the length of patients’ stays in field hospitals as short as possible and to only carry out emergency operations, leaving all other procedures to staff at base hospitals in the rear. Although field hospitals (as was the case for all military hospitals) were theoretically protected by international law,[12] they were still occasionally bombed, albeit seldomly on purpose.[13]

In contrast, base hospitals in the rear were in most cases better equipped, organised, and protected. They served to provide medical assistance to both the troops stationed in the rear and wounded and sick soldiers transferred to them from field hospitals.[14] Unlike in most field hospitals, female nurses were commonly employed in base hospitals.[15] Some of the German base hospitals for example, especially those located in France and Belgium, developed into big medical centres with good treatment possibilities.[16] However, this was not the case for all of these institutions and they were also faced with the constant danger of shelling.

Another type of hospital in the rear was the prisoner-of-war hospital. In some cases, for example in German prisoner-of-war hospitals, imprisoned enemy doctors treated injured or ill prisoners of war while being supervised by military surgeons.[17] Specialized prisoner-of-war hospitals also existed on the home front. Yet here, prisoners of war were mostly treated in regular military hospitals, while being closely supervised.[18] Hospitals in means of transportation were a further type of medical facility. In the British army, hospital ships played a major role in bringing injured soldiers from the Western Front back home.[19] Ambulance trains were also very common in the British, German, and French armies, sometimes offering fully equipped wagons with sickbeds, operating theatre facilities and medical supplies.[20] In many cases though, sick and wounded soldiers were transported to base or domestic hospitals in basic trains without any medical equipment (or staff).

By the time wounded or sick soldiers finally arrived at a home front hospital they had usually already been treated at one or several of the other hospital types. This might also explain why home front hospitals tended to be held in such high regard by soldiers, doctors and nurses alike. This is hardly surprising, when one takes the far more life-threatening and unpleasant conditions of field hospitals, base hospitals and hospital trains into account.[21]

Hospitals on the Home Front↑

For the severely injured and sick, military hospitals back home represented the most attractive locations to find medical care and rest. Hospitals were either run exclusively by the military, or managed and financed by voluntary aid associations such as the Red Cross or private providers.[22] In any case, such auxiliary hospitals were directly subordinated to a hospital run by the military in order to maintain as much military control as possible. Hospitals were mostly installed in large public or private buildings such as schools, museums, civilian hospitals, breweries, factories or ballrooms. In Paris, for example, the “Grand Palais”, which had initially been constructed for the International Exposition of 1900, was turned into a major hospital with over a thousand beds.[23] In other cases, temporary hospital barracks were built on large open spaces, such as the “Tempelhof Field” hospital in Berlin.[24] The high number and central location of military hospitals considerably changed urban space in many European cities and small towns during the war. Not only did the bodies of injured soldiers in the cities’ streets bear witness to the ongoing war, but also the military hospitals themselves indicated to the public that military priorities now superseded everything else. This led to a considerable “medicalization” of the home fronts, bringing modern medicine to centres of urban life and public awareness.[25]

However, hospital systems did not function smoothly from the beginning of the war onwards. In 1914, many hospitals close to the front and at home were overwhelmed by the large number of wounded and sick in need of help from the very first months of combat. Pre-war planning in all countries had completely underestimated the immense numbers of soldiers in need of medical care. In Germany, for example, the hospital system operated in a rather chaotic fashion during the first months of the war. Medical treatment was often insufficient due to lack of space, experience and medical facilities. Only after a month-long restructuring phase were military authorities and civilian organisations such as the Red Cross able to enlarge the hospital system. They did so by opening additional military hospitals, thus doubling the number of available beds. This finally allowed them to provide proper medical assistance to the high numbers of wounded and sick soldiers returning home from the war fronts.[26]

During the course of the war, the military medical authorities in all warring countries increasingly started to establish specialized hospitals and to build centres of competence in order to treat patients more efficiently. Hospitals were divided up, becoming centres specialised in the treatment of venereal diseases, gastro-intestinal diseases, psychiatric problems, and so on. In this way, patients found themselves in the same ward as other patients with similar ailments. This could strengthen the sense of fellow suffering and lift morale – an effect consciously created by military doctors and authorities. However, many surgeons complained that due to mismanagement patients often arrived too late in specialised hospitals to receive the treatment they needed. This was, for example, the case in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, in which many patients with facial injuries arrived at the hospital in Vienna after great delays, having stayed in several other hospitals. This made their treatment much more complicated and meant that possible previous treatment errors could no longer be fixed.[27]

Civilian hospitals continued to operate during the war albeit under deteriorating working conditions. Some of them were converted into military hospitals, others functioned partly as military and partly as civilian hospitals, and still others continued to treat only civilian patients. The increasing lack of physicians and nursing staff due to the war meant that conditions in civilian hospitals left much to be desired. In Britain, an increased demand for beds meant that civilian hospitals were repurposed for military needs. Asylums, such as Beaufon in Bristol, were converted into war hospitals and thus psychiatric patients were moved.[28] Medical care for civilians and public health also deteriorated dramatically in France and Germany.[29] This resulted in increasingly overcrowded hospitals. Food shortages, as well as sexual diseases, tuberculosis and the 1918 influenza pandemic impaired public health.[30] In Germany, all pre-war plans to enlarge and modernize city hospitals had been side-tracked. Therefore, civilian hospitals did not only lack space and medical staff, but also medical equipment.[31]

Civilian Engagement in Hospital Care↑

Most military hospitals were lively spaces in which numerous social encounters took place. It became highly popular for civilians to visit them and to provide charitable aid. Here, volunteer helpers, donors and artists, who tried to cheer the patients up with their performances, could publicly demonstrate their willingness to support the war effort and fulfil their national duty. Moreover, many men and women regarded military hospitals as fascinating “windows” to the battlefield, offering them insights into trench life whilst still being able to stay in the safety of their hometowns.[32] Clinics and their patients were one of the most visible signs of the war in their civilian world.[33] Although military authorities were suspicious of this rush of visitors and, in order to maintain military discipline, tried to restrict civil access to the sickbays, eventually they were no longer able to prevent hospitals developing into popular contact zones between military and civil society.

Civilian organisations and individual civilian benefactors played a major role in providing injured and sick soldiers with adequate and sufficient health care. In most warring countries, relief agencies, charity institutions, companies, and individuals committed themselves to supporting military medicine and hospital treatment. Most prominently, Red Cross societies were involved in hospital care.[34] Yet other actors offered great support as well, above all chivalric orders (Hospitalers, Knights of St. John and the St. George Order) and religious orders. Their contribution to the hospital system was significant: volunteer associations trained and employed a huge number of nurses and other medical auxiliaries, provided civil physicians, medical equipment, hospital laundry, furniture and complex administrative services. Most importantly, the Red Cross and other volunteer aid societies financed and managed a huge number of auxiliary hospitals – although they remained in the control of military surgeons and authorities.[35] Some hospitals were established on grounds belonging to the private estates of aristocrats and wealthy philanthropists. In Britain this was for example the case for those at Dunham Massey, Knutsford, and Bishop’s Knoll.[36] Another interesting example is Endell Street Military Hospital in London, a facility entirely staffed by women, most of them militant suffragists.[37] Civilian aid was a fundamental element of hospital care, and one which prevented it from collapsing given the enormous number of sick and wounded soldiers. However, at the same time, this implied that the military depended heavily on civilians – on their money, personnel, time capacities and resources – while the Red Cross and other civilian actors in turn were subjected to the military giving its consent for them to be able to carry out their relief activities.

In Germany, this situation of mutual interdependency created much friction and mutual distrust, especially on the side of the military. Civilian-led auxiliary hospitals, for instance, were under general military suspicion throughout the entire course of the war. In the eyes of German military officials, these clinics seemed to embody all the negative aspects of hospital care in a concentrated manner, such as a loss of discipline and combat morale among patients, effeminacy, misguided and unrealistic treatment objectives, lack of military control, and delayed discharge of patients. Increasingly, this general military distrust of civilians in hospital care culminated in accusations stating that auxiliary hospitals were impeding the rapid recovery of soldiers and hence obstructing the national war effort. In sum, the military authorities had to deal with a conflict of goals, attempting to shield military hospitals from too much civilian influence (through care-givers, visitors, etc.), while at the same time benefitting from the advantageous aspects of civilian involvement in hospital care. Above all, military authorities very much approved of the mobilising and integrating effect which hospitals evidently had on the civilian population.

The Patients’ Experience↑

Hospitals did not only fulfil the military goals of the army, but also fundamentally shaped the war experience of millions of soldiers in all warring countries. In the German army, statistically, each of the 13.2 million soldiers fell ill or were injured twice during the war. Of all of these cases, about one third were treated in hospitals at home, while the rest remained in hospitals closer to the front. Whereas many injured men died on the spot on the battlefield, later in field hospitals, or even in ambulance trains, hospitals at home were not predominantly places of death. Of the nine million “cases”[38] treated in hospitals in Germany, 114,489 patients died, that is, 1.3 percent.[39] The most common reason to be admitted to a clinic in Germany was illness, especially those respiratory, gastro-intestinal and dermatological in nature.[40] The same was true for field and base hospitals behind the lines and in the rear: again, in total, more soldiers suffered from various forms of diseases than from wounds.[41] Hence, the typical hospital patient was the sick serviceman.

How patients personally experienced their hospital stay depended on several factors: among others, on the type and severity of their injury or illness, on the facility they were brought to, and on the doctors, nurses and other hospital staff. On the other hand, despite all these differences, there still seem to be some facets of hospitalization that most soldier-patients shared and described: in the liminal space of the hospital, patients transitioned from illness to (some level of) health, from a military to a civilian existence, or from past to future military service. Hospitals – especially those at home – provided the sick and wounded with a respite from the life-endangering situations so prevalent in the trenches and provided them with weeks or months of rest in a safe and dry place. Ironically, in a situation of technologized trench warfare, painful disease and wounds could mean survival, whereas physical health potentially put a soldier’s life in great danger. As numerous soldiers’ diaries and letters show, hospital patients had – often for the first time in months – a clean bed with fresh linen, they could rest and experience a calm environment, they had enough food (except during periods of extreme food shortages) and were able to sleep. Many servicemen had never in their life entered a hospital before, especially if they came from a working-class background.[42]

In personal accounts such as letters, diaries and memories, many soldiers described field and base hospitals rather negatively. In many cases, patients had to struggle with insect infestations, humidity, overcrowded sickbays or tents, shortages of doctors, the suffering of their severely wounded fellow patients, and the threat of bombardments.[43] Hospitals at home, on the other hand, were often conceived as “counterplaces” to the life-threatening situations occurring in the trenches. Whilst the trenches carried with them a decidedly masculine connotation, central metaphors used in patients’ diaries to describe home front clinics were “purity”, “silence”, and “motherliness/femininity”.[44] In the eyes of many soldiers, hospitals at home were special microcosms offering a sense of everydayness and a reliable fulfilment of expectations, something that most of them had scarcely, if at all, experienced during active duty.

Life in hospital was characterized by recurrent medical routines. The soldiers were weighed, their temperature taken, their medicine delivered, and individual treatments performed. For some of the wounded patients, surgeries, too, were recurring events, albeit rather fear-evoking ones. As soon as hospital patients were on the mend, or if they only suffered from a benign disease, they often experienced significant personal freedom and were able to organise and plan their leisure time as they saw fit. Patients’ diaries and letters reveal how many different activities were organised by hospital personnel or initiated by soldiers themselves in order to counter boredom and melancholy. Common activities were trips to nearby cities, going to the cinema or to the theatre, joining patients’ drama groups, enjoying card and board games, etc.[45] In some cases, hospitals produced their own magazines to entertain the inmates and keep them informed about hospital-related developments. For today’s historians, they are a fascinating source for analysing the dominant forms of humour used, popular topics of discussion, and the character of military hospitals during the Great War.[46]

Most soldiers spent several weeks or months in military hospitals, in some cases even years. During such long stays, in the intimacy of the sickrooms, temporary communities of shared experience between patients emerged. In many cases, these were not friendships in a civilian sense, but rather resembled the comradeship of being in the trenches and the idea of fellow suffering. Indeed, for many soldiers, pain and suffering were a key feature of their hospital experience. Studies of British hospitals have shown, however, that many patients made enormous efforts to hide their pain and only articulated it in diaries. This silence surrounding suffering was an effect of the masculine culture of military hospitals, one which qualified utterings of pain as effeminate and childlike.[47]

Nevertheless, and despite all hardships, in a situation of industrialized warfare, hospitals – especially those on the home front – were seen by many soldiers as places of longing. It was common in many armies for soldiers to hope for a “blighty”, a “bonne blessure” or a “Heimatschuss”, meaning an injury which would necessitate the hospitalisation of a soldier without seriously harming him. Some servicemen went as far as to resort to malingering, self-mutilation, or the aggravation of existing ailments so as to prolong or necessitate a hospital stay.[48] Just how many soldiers made use of these practices is unknown. In any case they represented a constant threat to the military authorities, one that they monitored and battled rigorously. Still, these body practices do not only bear testimony to how attractive the military hospital seemed in the eyes of many servicemen. They also show the reluctance of an increasing number of soldiers to continue to endure the excruciating and unpredictable conditions of front life.[49]

Contact Zones↑

The Great War in general, but war hospitals in particular, brought together men and women from different social classes, genders, regions and nations. They can therefore be described as multifaceted social and cultural “contact zones”. The RAMC, for example, was composed of doctors from Britain and its dominions. Furthermore, nurses, orderlies, and masseuses from all over the British Empire staffed the Red Cross hospitals and other war clinics, in which medical practices from England, Scotland, Canada, and Australia were connected.[50] Hospitals in all belligerent countries were places in which various different kinds of encounters took place, and this on many levels. Here, doctors exchanged scientific ideas, young nurses and helpers built a new life outside their parents’ home, religious hospital operators reached out to soldiers and authorities, schoolchildren and other external visitors from cities in which hospitals were situated visited what one might term the “medical realm”. Another important group of visitors were family members and friends of hospital inmates. For many servicemen, hospitalization was one of the few occasions – apart from home leave – to see their family members again after months or years of separation. Certainly, not all families could afford the travel expenses for a hospital visit, but many others made use of these rare occasions to see their loved ones.[51] Hospitalized soldiers also came into more regular contact with women. This was especially true for nurses and other female staff, but also applied to female visitors or local women whom the soldiers met when venturing out into the cities or towns in which the hospitals were located. Studies have shown that hospitals were a place not only of military discipline, but also of intimacy and even sexuality between patients, nurses, and other female staff and visitors.[52]

On another level, the military hospital also functioned as a contact zone by bringing together sick and wounded soldiers from enemy countries. It was one of the few places during the war where they could peacefully meet.[53] In Germany, prisoners of war were sometimes treated in specialized prisoners’ hospitals. Yet much more frequently they stayed in the same military hospitals as injured German soldiers, often even in the same wards. These encounters had ambivalent outcomes. On the one hand, some accounts by soldiers, nurses and other hospital staff comment on mutual respect and even friendships between fellow patients from enemy states. On the other hand, hostility and established stereotypes about “the Other” also persisted or were reinforced. It seems that while the hospital facilitated contact between patients from enemy countries this did not necessarily challenge or change pre-war stereotypes.

While the boundaries between soldiers of different social, national, and cultural backgrounds, as well as the difference between soldiers and civilians, were, to a certain extent, blurred within the hospital, these categories were also reinforced by symbolic demarcations. Hospital inmates were denoted by a particular hospital uniform. This distinguished them from the civilian population and was supposed to ensure hygiene as well as institutional discipline and order. In Britain, hospital inmates had to wear a blue uniform known as “convalescent blues”. It was made of a combination of flannel and flannelette, issued by the government and often fit poorly, as only a handful of standardized sizes existed.[54] In Germany, soldier-patients on the home front had to wear a blue-and-white-striped hospital outfit.[55] Before being admitted to hospital, they had to hand in their field uniform and larger personal items. This procedure further manifested their transition from soldier to patient. Additionally, prisoners of war in hospitals had to wear special badges attached to their hospital clothes. This was meant to prevent even the slightest possibility of them being confused with German soldiers and mingling with them too much.[56]

Rehabilitation and Re-education↑

During the Great War, for the first time, the idea arose that even severely disabled soldiers should be rehabilitated and returned to the job market in order to be able to earn their own income and not simply live off a pension.[57] They should continue to support the national war effort. This new perspective was partly due to an optimistic feasibility paradigm of modern medicine, and partly simply to financial and military reasons. Countries like Germany or the Austro-Hungarian Empire could not afford to pay for thousands of unemployed invalids, particularly as they did not have many alternatives when it came to replacing manpower in the army and industry. Hospitals were crucial places for implementing the new approach of rehabilitation. Military surgeons and officials viewed hospitals as ideal training spaces for invalids to successfully prepare for their re-entry into the job market. While they were still in hospital, disabled soldiers could be supervised, controlled and ordered to undergo physiotherapy, to use artificial limbs in curative workshops, and to get to grips with other orthopaedic devices. After being discharged, however, military surgeons and civil relief associations could not exert influence on them as easily.

The military authorities sought to foster patients’ “will to work” as well as their “recovery will” through suitable hospital occupations. These working activities were supposed to prevent idleness and “war-weariness”. Common occupations were gardening, basket-weaving, knotting and carving. Some hospitals had fully equipped workshops with instructors available to help disabled patients become well enough to be able to take up their original job again, or to re-educate them for a new career. In Germany, disabled soldiers were even encouraged to work in factories during the daytime in order to reintegrate them smoothly into the job market. Additionally, they could attend educational classes in specialised schools for the wounded. Some of these orthopaedic hospitals gained international fame. This was for example the case for the Vienna schools for the war disabled, connected to military hospital No. 11 and led by Austrian orthopaedist Hans Spitzy (1872-1956). The hospital offered a wide range of training and treatment methods for disabled soldiers and formed a little “invalid city” within Vienna.[58]

However, the elaborate rehabilitation framework conceptualised by orthopaedists and military officials did not always yield the desired results. In the German and British case for example, certain patients were reluctant to take part in curative work and subtly or overtly resisted the programmes.[59] In other cases, war hospitals themselves were not equipped or willing to offer the injured a sophisticated work-training programme. Therefore, orthopaedic clinics could not always meet the high expectations geared towards them and the theoretical concepts did not always match up with the reality of invalids and everyday life in hospital.

Hospitals as Military Institutions↑

From an army perspective, all hospitals had to fulfil four main functions: medical, military, socio-economic and representative. Their medical function was to cure soldiers’ bodies. Yet their more important military function was to restore the military fitness or economic capability of patients as quickly and effectively as possible. Consequently, military hospitals were not supposed to operate according to the logic underlying civilian medicine – “healing” a soldier and restoring health – but had to meet mainly military requirements. Doctors were supposed to examine how physically healthy the injured or sick soldier could become through hospital treatment in a reasonable amount of time. If a soldier’s healing process took a disproportionately long time, he was meant to be discharged.[60] In this case, civilian agencies had to take charge of the men’s subsequent rehabilitation. Alternatively, and this relates to the economic function of hospitals, officials tried to integrate disabled patients into the labour market at the end of their hospital stay. To this end, many clinics provided curative workshops, career counselling, re-education classes and other measures. These were meant to foster the economic and social re-integration of war invalids from the very beginning and save the state the expense of having to pay pensions.

The representative function of hospitals played an especially important role in Germany. Military medical officials and physicians tried to prove through their hospitals that firstly, German medicine was at the forefront of modern science and played a crucial role in the national war effort. Secondly, hospitals were supposed to disconfirm allegations against Germany that it was a barbaric country, having committed war atrocities in France and Belgium. To this end, military officials and physicians used hospitals as a means of spreading counter-propaganda. Berlin-based surgeon Carl Ludwig Schleich (1859-1922) wrote in a 1916 newspaper article that critics should simply “take a walk through one of our military hospitals” in order to see that the German nation “stands at the forefront of all civilized nations”.[61] A country that cares so much for its wounded soldiers could not be called “barbaric” without “completely distorting the obvious facts.”[62]

Hospital treatment should be as short and effective as possible. However, military officials often wondered if clinics at home really fulfilled this task. In Germany especially, authorities had a highly ambivalent image of their military and auxiliary hospitals. Did they actually help to alleviate manpower shortages at the front? Or did they rather pose a threat to social order and undermine patients’ readiness for fighting? Above all, German military officials feared that long-term hospitalisation on the home front would distance patients from military life and cause social unrest. They feared that they would lose control over both the readiness of patients to enter combat and their general states of mind if they were to allow them to stay in hospitals for too long. German medical officials considered a maximum of two months to be an adequate and, above all, unsuspicious time span for recoveries. As much as they viewed hospitals as indispensable military tools, they also perceived them as highly problematic, somewhat inscrutable places. Therefore, hospital stays always seemed to carry the risk of causing collateral social damage. Dr. Karl Frickhinger, a councillor and medical officer in the city of Würzburg, urgently warned against extended hospitalisation, from a psychological point of view:

Statements like this one reveal that German medical officers did not only view quick discharges of patients as an abstract economic necessity. At the same time, the demand for speed could be used as a powerful administrative tool in order to get rid of hysteric patients, or those that repeatedly fell ill – two problems that were often viewed as one and the same. In this fashion, medical officers hoped to counter the danger of waning discipline in hospitals at home. Hospitals should be, on the contrary, places to re-discipline soldiers.

Patients were often suspected of either malingering or of aggravating existing symptoms so as to delay having to return to service, particularly if a patient’s clinical presentation was unclear in some way. This suspicion did not only apply to soldiers suffering from shell shock and other psychological disorders, but also to those with internal diseases such as rheumatism, kidney, heart or bladder diseases, back pain or venereal disease. Because of the growing distrust and fear that patients with alleged symptoms might be using unreliable hospitals as their hiding places, the German authorities ordered ever more control measures. Hospitals therefore became places subjected to increasingly rigid surveillance practices and disciplinary measures. However, it was impossible for the authorities to ever achieve total control over the hospital system.

Conclusion↑

Military hospitals can be understood as “liminal spaces” between the civilian and military spheres. They represented ambivalent intermediate areas in which, during the course of the war, different social and military ideas and interests collided. This made constant negotiation necessary. From a military perspective, hospitals were sites for the re-construction and further “improvement” of soldiers’ bodies, minds and identities. Their main military purpose was to send as many patients as possible back to the front or to find ways of enabling them to contribute to the war effort in a civilian job. In addition, hospitals at home in particular developed into lively social “contact zones”. Here, not only did soldiers, nurses, visitors, and prisoners of war meet, but different realms of society also came into contact with one another. This led to new encounters, new conflicts, and increasing allocation battles between military and civilian actors. Hospitals were also crucial parts of soldiers’ war experiences. How patients perceived hospitalization varied from individual to individual, depending heavily on external circumstances (such as whether the hospital was located close to, or far away from, the front) and was rather ambivalent for most servicemen. In many cases their experience oscillated between negative emotions such as helplessness, physical pain and anxiety about the future, and positive experiences revolving around feelings of relief, comfort and community. While hospitals close to the front were often provisional, chaotic, and sometimes highly dangerous places where the horrors of the war became blatantly obvious, hospitals back home could be very comfortable and welcoming. For some soldiers, hospitals at home became places of longing and they tried to inhabit these spaces for as long as possible, trying to avoid being sent back to the front at all costs. This created tensions with military surgeons and authorities. From a military perspective, the hospital was supposed to strengthen morale and combat-readiness amongst patients. It was not meant to become a popular destination with a life of its own.

Alina Enzensberger, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München

Section Editor: Michael Geyer

Notes

- ↑ Harrison, Mark: The Medical War. British Military Medicine in the First World War, Oxford 2010, p. 120.

- ↑ Remarque, Erich Maria: All Quiet on the Western Front, London 1930.

- ↑ See Enzensberger, Alina: Übergangsräume. Deutsche Lazarette im Ersten Weltkrieg, Göttingen 2021; other exceptions are the hospital sections in Eckart, Wolfgang: Medizin und Krieg. Deutschland 1914-1924, Paderborn et al. 2014; Ruff, Melanie: Gesichter des Ersten Weltkrieges. Alltag, Biografien und Selbstdarstellungen von gesichtsverletzten Soldaten, Stuttgart 2015; Perry, Heather R.: Recycling the Disabled. Army, Medicine and Modernity in WWI Germany, New York 2014; Bergen, Leo van: Before My Helpless Sight. Suffering, Dying and Military Medicine on the Western Front, 1914-1918, Aldershot et al. 2009. British hospitals, on the other hand, have featured much more broadly in academic works, especially in Carden-Coyne, Ana: The Politics of Wounds. Military Patients and Medical Power in the First World War, Oxford et al. 2014; Reznick, Jeffrey S.: Healing the Nation. Soldiers and the Culture of Caregiving in Britain During the Great War, Manchester 2004; Bourke, Joanna: Dismembering the Male. Men’s Bodies, Britain and the Great War, London 1996.

- ↑ See Reid, Fiona: Medicine in First World War Europe. Soldiers, Medics, Pacifists, London 2017, pp. 33-39.

- ↑ For more on the structure of the German army medical service see Enzensberger, Übergangsräume 2021, pp. 29-43.

- ↑ The German terms for this are “Medizinal-Abteilungen der Kriegsministerien” and for the regional offices “Sanitätsämter der Stellvertretenden Generalkommandos.” For more on this structure see Enzensberger, Übergangsräume 2021, pp. 34-42; Heeres-Sanitätsinspektion des Reichskriegsministeriums: Sanitätsbericht über das Deutsche Heer (Deutsches Feld- und Besatzungsheer) im Weltkriege 1914-1918 (Deutscher Kriegssanitätsbericht 1914-1918). Gliederung des Heeressanitätswesens im Weltkriege 1914/1918, volume 1, Berlin 1935, pp. 157-175.

- ↑ For the German naval hospitals see the statistical report from the 1930s Marinemedizinalamt des Oberkommandos der Kriegsmarine (ed.): Kriegssanitätsbericht über die Deutsche Marine 1914-1918, 3 volumes, Berlin 1934.

- ↑ The experiences of nurses in base (and sometimes field) hospitals are covered for example in Fell, Alison: Nursing the Other. The Representation of Colonial Troops in French and British First World War Nursing Memoirs, in: Das, Santanu (ed.): Race, Empire and First World War Writing, New York 2011, pp. 158-174; Fell, Alison / Hallett, Christine (eds.): First World War Nursing. New Perspectives, London 2013.

- ↑ For more on field hospitals in Britain, France and Germany see Van Bergen, Before My Helpless Sight 2009, pp. 312-322.

- ↑ CCSs were at first called “hospitals” instead of “stations”, but this was soon altered to keep expectations low. For more on the CCSs see Harrison, The Medical War 2010, esp. pp. 32-43.

- ↑ For example in Frank, Leonhard: Die Kriegskrüppel [1919], in: Frank, Leonhard: Der Mensch ist gut, Munich 1964, p. 120; Schäfer, Daniel: Stilles Heldentum. Lazarett-Bilder, Berlin 1928, p. 48.

- ↑ See mainly Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armies in the Field, Geneva, 6 July 1906, chapter 2, § 6-8.

- ↑ Enzensberger, Übergangsräume 2021, p. 30.

- ↑ Van Bergen, Before My Helpless Sight 2009, pp. 322-332.

- ↑ For the German case: Eckart, Medizin und Krieg 2014, p. 106; Stölzle, Astrid: Kriegskrankenpflege im Ersten Weltkrieg. Das Pflegepersonal der freiwilligen Krankenpflege in den Etappen des Deutschen Kaiserreichs, Stuttgart 2013.

- ↑ Kolmsee, Peter: Unter dem Zeichen des Äskulap. Eine Einführung in die Geschichte des Militärsanitätswesens von den frühesten Anfängen bis zum Ende des Ersten Weltkrieges, Bonn 1997, pp. 187-188.

- ↑ Heeres-Sanitätsinspektion, Sanitätsbericht 1935, volume 1, p. 126.

- ↑ For the British case see Carden-Coyne, The Politics of Wounds 2014, pp. 205-207.

- ↑ Harrison, The Medical War 2010, pp. 58-59; Reid, Medicine 2017, p. 28.

- ↑ Van Bergen, Before My Helpless Sight 2009, pp. 322-324; Großheim, Carl: Der Verwundetentransport bei der Armee, Berlin 1915.

- ↑ Enzensberger, Übergangsräume 2021, pp. 30-31.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 69-75.

- ↑ Reid, Medicine 2017, p. 63.

- ↑ For more on the “Tempelhof Field” hospital see Brettner, Hans: Aus dem Barackenlazarett auf dem Tempelhofer Felde, in: Zeitschrift für Krüppelfürsorge 9 (1916), pp. 183-185.

- ↑ Eckart, Medizin und Krieg 2014, pp. 122-123.

- ↑ For more on the first months of the war in German hospitals see Enzensberger, Übergangsräume 2021, pp. 52-66; Osten, Philipp: Militärmedizin – unvorbereitet in die Krise, in: Deutsches Ärzteblatt 112 (2015), pp. 370-373; Thomann, Klaus-Dieter: Die medizinische und soziale Fürsorge für die Kriegsversehrten in der ersten Phase des Krieges 1914/15, in: Eckart, Wolfgang / Gradmann, Christoph (eds.): Die Medizin und der Erste Weltkrieg, Pfaffenweiler 1996, pp. 183-196.

- ↑ Ruff, Gesichter 2015, pp. 119-121.

- ↑ See Carden-Coyne, The Politics of Wounds 2014, p. 194.

- ↑ Murard, Lion / Zylberman, Patrick: The Nation Sacrificed for the Army? The Failing French Public Health, 1914-1918, in: Eckart / Gradmann (eds.), Die Medizin 1996, pp. 343-364.

- ↑ Michels, Eckard: Die “Spanische Grippe” 1918/19, in: Vierteljahreshefte für Zeitgeschichte 58 (2010), pp. 1-33; Barry, John M.: The Great Influenza. The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague in History, New York 2004.

- ↑ For more on the hospital situation in the war and postwar period see Hauner, Franz: Licht, Luft, Sonne, Hygiene. Architektur und Moderne in Bayern zur Zeit der Weimarer Republik, Berlin et al. 2020, pp. 131-195, esp. pp. 131-132; 151-152.

- ↑ Enzensberger, Übergangsräume 2021, pp. 69-91.

- ↑ See also Kienitz, Sabine: Beschädigte Helden. Kriegsinvalidität und Körperbilder, 1914-1923, Paderborn et al. 2008, esp. p. 22.

- ↑ For more on the Red Cross societies see Oppenheimer, Melanie: The Power of Humanity. 100 Years of Australian Red Cross, Sydney 2014; Irwin, Julia: Making the World Safe. The American Red Cross and a Nation’s Humanitarian Awakening, New York 2013; Eckart, Wolfgang / Osten, Philipp (eds.): Schlachtschrecken – Konventionen. Das Rote Kreuz und die Erfindung der Menschlichkeit im Kriege, Freiburg 2011.

- ↑ Harrison, The Medical War 2010, p. 59.

- ↑ Carden-Coyne, The Politics of Wounds 2014, p. 194.

- ↑ See Geddes, Jennian F.: Deeds and Words in the Suffrage Military Hospital in Endell Street, in: Medical History 51 (2007), pp. 79-98.

- ↑ German medical statistics did not count individual patients but only cases. In this way, many soldiers featured several times in the statistical records. For more on this counting method see Whalen, Robert Weldon: Bitter Wounds. German Victims of the Great War, 1914-1939, Ithaca et al. 1984, p. 40.

- ↑ Heeres-Sanitätsinspektion, Sanitätsbericht 1935, volume 3, p. 100, chart 67.

- ↑ Ibid., appendix, chart 17.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Carden-Coyne, The Politics of Wounds 2014, p. 194.

- ↑ For a comparative perspective on this see Van Bergen, Before My Helpless Sight 2009, pp. 312-332.

- ↑ On the basis of personal accounts from German soldiers see Enzensberger, Übergangsräume 2021, pp. 167-170; 191-200.

- ↑ For more on the German patients’ perspective, see also “Nicht nur Menschen, sondern auch viel Zeit muß gegenwärtig totgeschlagen werden”, issued by Muße. Ein Magazin, online: http://mussemagazin.de/?p=910 (retrieved: 10 December 2020); concerning the experiences of French patients with facial injuries see Gehrhardt, Marjorie: The Men with Broken Faces. Gueules Cassées of the First World War, Oxford et al. 2015.

- ↑ For German hospital magazines see Enzensberger, Übergangsräume 2021, pp. 223-225; 237; for the British case see Reznick, Healing the Nation 2004, pp. 65-98.

- ↑ Carden-Coyne, Ana: Men in Pain. Silence, Stories and Soldier’s Bodies, in: Cornish, Paul / Saunders, Nicholas (eds.): Bodies in Conflict. Corporeality, Materiality, and Transformation, London et al. 2014, pp. 63-64.

- ↑ For more on this see Trogh, Pieter: About Blighties and Bonnes Blessures. Self-inflicted Wounds as a Means to Cope with the Hardships of the First World War?, in: Bergen, Leo van / Vermetten, Eric (eds.): The First World War and Health, Leiden 2020, pp. 322-345; Bourke, Dismembering the Male 1996, pp. 78-107; for the German case see Enzensberger, Übergangsräume 2021, pp. 263-266; 298-304.

- ↑ For a more general approach to the question of the endurance and coping strategies of soldiers see Beaupré, Nicolas / Jones, Heather / Rasmussen, Anne (eds.): Dans la guerre 1914-1918. Accepter, endurer, refuser, Paris 2015; Watson, Alexander: Enduring the Great War. Combat, Morale and Collapse in the German and British Armies, 1914-1918, Cambridge 2008.

- ↑ Carden-Coyne, The Politics of Wounds 2014, pp. 196-197.

- ↑ For discussions of this issue in Britain see Harrison, The Medical War 2010, p. 61.

- ↑ Carden-Coyne, The Politics of Wounds 2014, pp. 196-235; Enzensberger, Übergangsräume 2021, pp. 235-246.

- ↑ This idea is also reflected in the poem The German Ward by Vera Brittain, issued by The First World War Poetry Digital Archive, online: http://ww1lit.nsms.ox.ac.uk/ww1lit/collections/item/1745 (retrieved: 28 February 2021). Also printed in Bergen, Leo van: A Cap of Horror, Nijmegen 2020, p. 26.

- ↑ See for example Winter, Jay: Hospitals, in: Winter, Jay / Robert, Jean-Louis (eds.): Capital Cities at War. Paris, London, Berlin, 1914-1919, volume 2, Cambridge et al. 2007, pp. 355-360.

- ↑ Enzensberger, Übergangsräume 2021, pp. 166-167.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 229.

- ↑ For more on the concept of rehabilitation see Perry, Recycling the Disabled 2014; Anderson, Julie / Perry, Heather R.: Rehabilitation and Restoration. Orthopaedics and Disabled Soldiers in Germany and Britain in the First World War, in: Medicine, Conflict and Survival 30 (2014), pp. 227-251.

- ↑ Pawlowsky, Verena / Wendelin, Harald: Die Wunden des Staates. Kriegsopfer und Sozialstaat in Österreich 1914–1938, Vienna 2015, pp. 117-123.

- ↑ Enzensberger, Übergangsräume 2021, pp. 144-146 and 153-158.

- ↑ Enzensberger, Alina: No Time to Waste. How German Military Authorities Attempted to Speed up the Recovery of Soldiers in Home-Front Hospitals, 1914-1918, in: Halewood, Louis / Luptak, Adam / Smyth, Hanna (eds.): War Time. First World War Perspectives on Temporality, London et al. 2018, pp. 15-35.

- ↑ Schleich, Carl Ludwig: Zwei Jahre kriegschirurgischer Erfahrungen aus einem Berliner Lazarett, Stuttgart et al. 1916, p. 1.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 2.

- ↑ Frickhinger, Karl: Lazarettunterricht, in: Münchener Medizinische Wochenschrift 62 (1915), p. 967.

Selected Bibliography

- Bourke, Joanna: Dismembering the male. Men's bodies, Britain and the Great War, Chicago 1996: University of Chicago Press.

- Carden-Coyne, Ana: The politics of wounds. Military patients and medical power in the First World War, Oxford 2014: Oxford University Press.

- Cohen, Deborah: The war come home. Disabled veterans in Britain and Germany, 1914-1939, Berkeley 2008: University of California Press.

- Crofton, Eileen: The women of Royaumont. A Scottish women's hospital on the Western Front, East Linton 1997: Tuckwell Press.

- Delaporte, Sophie: Les médecins dans la Grande Guerre, 1914-1918, Paris 2003: Bayard.

- Eckart, Wolfgang Uwe: Medizin und Krieg. Deutschland 1914-1924, Paderborn 2014: Ferdinand Schöningh.

- Enzensberger, Alina: Übergangsräume. Deutsche Lazarette im Ersten Weltkrieg, Göttingen 2021: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- Fell, Alison S / Hallett, Christine E (eds.): First World War nursing. New perspectives, London 2013: Routledge.

- Gehrhardt, Marjorie: The men with broken faces. Gueules cassées of the First World War, Oxford; Berlin 2015: Peter Lang.

- Harrison, Mark: The medical war. British military medicine in the First World War, Oxford; New York 2010: Oxford University Press.

- Moncrieff, Alexia: Expertise, authority and control. The Australian Army Medical Corps in the First World War, Cambridge 2020: Cambridge University Press.

- Pawlowsky, Verena / Wendelin, Harald: Die Wunden des Staates. Kriegsopfer und Sozialstaat in Österreich nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg 1914-1938, Vienna 2015: Böhlau.

- Perry, Heather R.: Recycling the disabled. Army, medicine, and modernity in WWI Germany, Manchester 2014: Manchester University Press.

- Reid, Fiona: Medicine in First World War Europe. Soldiers, medics, pacifists, London 2017: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Reznick, Jeffrey S.: Healing the nation. Soldiers and the culture of caregiving in Britain during the Great War, Manchester; New York 2004: Manchester University Press.

- Ruff, Melanie: Gesichter des Ersten Weltkrieges. Alltag, Biografien und Selbstdarstellungen von gesichtsverletzten Soldaten, Stuttgart 2015: Franz Steiner Verlag.

- Van Bergen, Leo: Before my helpless sight. Suffering, dying and military medicine on the Western Front, 1914-1918, Farnham; Burlington 2009: Ashgate.

- Viet, Vincent: La santé en guerre, 1914-1918. Une politique pionnière en univers incertain, Paris 2015: Sciences Po, Les Presses.

- Whalen, Robert Weldon: Bitter wounds. German victims of the Great War, 1914-1939, Ithaca 1984: Cornell University Press.

- Winter, Jay: Hospitals, in: Winter, Jay / Robert, Jean-Louis (eds.): Capital Cities at War. Paris, London, Berlin, 1914-1919, volume 2, Cambridge 2007: Cambridge University Press, pp. 354-382.