Preparation↑

In the fall of 1917 the armies on both sides were equally worn by a war that seemed endless. With the Eleventh Battle of the Isonzo in August 1917, the Italian army had been able to conquer the upland of Bainsizza. By the end of the fighting, the Austro-Hungarian command realized that it would not be able to repel a further Italian attack, even if it were to be conducted at the end of autumn 1917 or in the following spring. Consequently, the Austrian command decided to demand help from its German ally to prepare an offensive that would force the Italians to retreat and that would provide relief to the weakened imperial army. Initially, the Germans rejected the requests for help. The leaders of the German army and Wilhelm II, German Emperor (1859-1941) regarded the Italian front as secondary and of little interest. However, the decision was reconsidered because the Germans feared a defeat of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, a prospect unthinkable for them. This was the first occasion on which the Germans decided to provide assistance to their Austro-Hungarian allies on the Italian front. They immediately began to study which strategy to adopt and formed a new 14th Army with nine Austrian and six German divisions, commanded by the German Otto von Below (1857-1944).

On 18 September 1917, General Luigi Cadorna (1850-1928), army chief of staff and supreme commander, ordered the army to adopt a defensive stance. However, the directives were generic and unclear, and the officials’ performance was equally inadequate. The following month, the general repeated the order, but once again the directives were not accurate and he did not ensure exact execution.

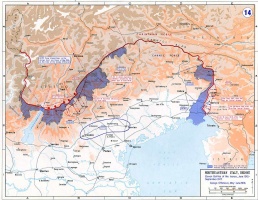

The winter was quickly approaching and the Germans and Austrians could not linger any longer. They began preparations for the offensive at a frantic pace. The plan of action included an intense attack in the upper of the Isonzo, north of the Tolmino bridgehead, with a more limited attack from the Plezzo’s basin. The plan was based on the assumption that the Italian defenses would be relatively weak at the end of the left side of General Luigi Capello’s (1859-1941) Second Army.

In addition to these strategic plans, the Germans and Austrians carefully studied the surprise effect. They concealed the 14th Army’s arrival as long as possible and did not prepare artillery shots. Another key element of the Austro-German planning was the use of infiltration. After a short but powerful bombardment of enemy lines, light infantry advanced to the trenches in order to penetrate and isolate the enemy positions.

The Battle↑

At two o’clock in the morning on 24 October 1917, the great Austro-German offensive began. Over the next hours, they fired thousands of explosive grenades and gas. There was no prolonged bombing of the Italian lines but the action was very intense, with the primary aim of making communication impossible. The objective was fully achieved, leaving troops and backline without orders and unable to pass on the situation. After the bombing, the infantry advance began, composed of well-rested men, not tired and weary like the Italian soldiers. The weather, characterized by a heavy fog that made visibility difficult for the defense troops, facilitated the assault, but it was the infiltration tactic which allowed the Austro-Germans to conquer the Italian trenches. The troops did not attack in compact groups but rather in small platoons: they were agile and independent, penetrated the enemy ranks and infiltrated deep behind the lines, taking the Italians by surprise from behind.

The Austro-German troops quickly reached the mountain range dominating the plain of Friuli region and assumed a dominant position from which they threatened most of the Italian backline deployed east of Isonzo. The attackers in the valley marched almost unopposed; some advanced a remarkable twenty-five kilometers during the first day.

With the penetration of the enemy and the disruption of communications, the Italian troops began to fall apart. The soldiers without serious injuries began to form an enormous river of people, seemingly without a destination, which is still one of the symbols of the battle. The news about the breakup of the front between Plezzo and Tolmino, toward Caporetto, arrived at the Supreme Command in the afternoon of 24 October 1917. General Cadorna sent out the first orders only between six o’clock in the morning and eleven o’clock at night. The Austro-German surprise was therefore total.

For the Italians, the situation was aggravated by the failure to establish and train reserve troops and by the absence of a defined plan for a possible retreat. The commander of the Second Army, General Capello, deliberately ignored Cadorna’s orders about the defensive placement of the troops and underestimated the news about the imminent attack until it was too late.

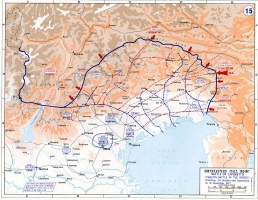

In the night between 26 and 27 October 1917, General Cadorna ordered the withdrawal of the Second and Third Army from the Tagliamento River. He also ordered the immediate evacuation of the Carnia and Cadore areas: 1.5 million men left the positions where they had fought and for which they had died for more than two years. On 27 October 1917, the commander of the Italian army issued a report accusing the Second Army of surrendering to the enemy without fighting.

On 27 October 1917, the Austro-German troops had already arrived in Cividale; the following day they conquered Udine and on 29 October 1917 they had almost reached the Tagliamento River. When the troops reached the river, the Italian Third Army had already crossed it or was about to do so. Advancing more deeply into the territory was impossible; the Italian defeat was such that even the attackers were surprised and did not have the forces to fully exploit the success. In the end, Berlin asked to relocate the mobilized men and material – even these troops were unprepared for so sudden a change from trench warfare to a movement war.

The End↑

At the end of the offensive, the Italian army counted 11,000 dead, 29,000 wounded, 300,000 prisoners and about another 300,000 scattered men. On the Austro-German side, the losses were around 50,000 men killed or wounded.

Italian troops were positioned on the Piave where they resisted and reorganized, since here they could establish a new defensive line. After the defeat of Caporetto, the Allies sent troops to support the Italian army that was laboriously rearranging itself. They were reinforced by six French and five British infantry divisions. Prior to the battle, in mid-October 1917, the new Italian government was formed, headed by Vittorio Emanuele Orlando (1860-1952). He requested and obtained Cadorna’s replacement. Although this decision had been made before the defeat of Caporetto, its execution was suspended after the battle in order to not complicate the operations of the withdrawn troops. The task was entrusted to General Armando Diaz (1861-1928), who served until 1919 and was nominated Duke of Victory at the end of the conflict.

Anna Grillini, University of Trento and Italian-German Historical Institute

Section Editor: Marco Mondini

Selected Bibliography

- Isnenghi, Mario / Rochat, Giorgio: La grande guerra, 1914-1918, Scandicci 2000: La nuova Italia.

- Labanca, Nicola: Caporetto. Storia di una disfatta (2 ed.), Florence 2000: Giunti; Casterman.

- Schaumann, Walther / Schubert, Peter: Isonzo, 1915-1917. Krieg ohne Wiederkehr, Bassano del Grappa 1993: Ghedina & Tassotti.

- Silvestri, Mario: Caporetto. Una battaglia e un enigma, Milan 1984: A. Mondadori.

- Silvestri, Mario: Isonzo 1917, Torino 1965: Einaudi.