Introduction↑

These words, introducing New Zealand’s First World War Centenary Programme, accurately describe the impact of the war on the nation. In terms of the number of combatants killed, it remains the costliest overseas conflict in New Zealand history and the trauma, we argue, is yet to be exorcised from the national psyche. Yet once the war generation had died there was surprisingly little knowledge of the war or its impact in New Zealand. There was an intriguing revival of interest among historians from the turn of the 21st century, but this was not widely shared outside that group until the centenary. The centenary offered a unique opportunity, with the support of public funds, to heighten awareness about the course and legacy of the First World War. This article explores the different ways the war was commemorated, from memorials and publications through to exhibitions, art works and community events. It draws most of the evidence from the listing of projects on the Manatū Taonga, the Ministry of Culture and Heritage’s WW100 website. This very rich government-sponsored archive illustrated the central role that digital resources played in the dissemination of information and knowledge during the centenary. The article concludes that the First World War Centenary Programme achieved a remarkable engagement among many sectors of the New Zealand population, and expanded knowledge of the conflict beyond a small circle of historians.

Knowledge of the First World War before the Centenary↑

20th Century↑

About 100,000 mostly young New Zealand men served in the First World War in response to the United Kingdom’s call for support from its empire. The first substantial commitment was taking part in the invasion of Turkey at Gallipoli in 1915. The largest engagement of New Zealand soldiers was on the Western Front from 1916-1918; and some mounted troops also served in the Middle East during those years. Over half of the servicemen were either killed or injured. In the years immediately after the return of the soldiers, the memory of the war was kept alive in the stories and memories of families, through the erection of over 500 community war memorials which became the site of the annual (25 April) Anzac Day commemoration, and in a series of official publications. But these books were in general poorly written and inaccessible and went out of print. New Zealand lacked a great historian of the war like Australia’s Charles Bean (1879-1968), who understood the role of historiography in his country’s nation-building story. Although the Auckland War Memorial Museum maintained a thin display about war, this was never a primary focus of the institution. New Zealand lacked a museum with the status and popularity of the Australian War Memorial.

So by the last half of the century there was little public interest in the Great War, nor research among historians, with the notable exceptions of Christopher Pugsley’s outstanding book on Gallipoli and Maurice Shadbolt’s (1932-2004) collection of interviews with Gallipoli veterans.[2] Attendance at the annual Anzac Day services declined. The fiftieth and seventy-fifth anniversaries of the First World War passed with little public comment. War memorials were often left in a bad state of neglect. To the extent that New Zealanders did know about the war they emphasised particularly the landing at Gallipoli, a site where only about 17,000 soldiers served and under 3,000 died of the total 18,000 war dead.[3]

2000-2013↑

From the turn of the 21st century there was a striking quickening of interest in New Zealand’s experiences during the First World War. Exactly why this happened is unclear. It was in part a reflection of a burgeoning cultural nationalism in New Zealand and a recognition that the First World War was a crucial moment in the development of New Zealand identity and deserved attention for that reason. As grandfathers who had been veterans of the war died, families sought to remember their service. Helen Clark, who was prime minister from 1999 to 2008, was a crucial influence. Members of her family had served and died in the war and she understood the role remembrance can play in shaping the identity of New Zealand both internally and internationally.

During Clark’s leadership a striking New Zealand memorial was unveiled in Canberra on Anzac Parade; and another distinguished memorial was opened at Hyde Park Corner in London. Then on Armistice Day (11 November) 2004, on Clark’s initiative, a tomb of the unknown warrior was unveiled in front of the National War Memorial Carillon in Wellington. She also promoted the construction of a walking track at Gallipoli from No. 2 Outpost to the summit of Chunuk Bair, which followed the New Zealanders’ advance in August 1915. A growing sense that many soldiers had not been conventional heroes, but victims of the war found expression in parliament’s 2000 decision to posthumously pardon five New Zealand soldiers who had been executed on the Western Front for disciplinary reasons.

There was also a flood of publications in these years. Perhaps historians were anticipating the centenary; or impelled by the growing academic and public interest in New Zealand history. A number of the finest works were written by former or current officers of the New Zealand Defence Force: Christopher Pugsley, Glyn Harper, and Terry Kinloch.[4] Unsurprisingly, therefore, the focus of these works was upon the military history of the war. There were also publications about individual soldiers, many of them collections of letters or diaries.[5]

During these years a significant influence in expanding popular interest was the Māori Television channel, which developed a rich programme about the history of the war and played it on Anzac Day each year.

By 2012 a survey suggested that about half of New Zealanders aged fifteen or over (47 percent) claimed a basic understanding of the First World War, with another third (31 percent) having a reasonable or advanced knowledge. But under half knew the dates of the war and far more were able to recall the name of Gallipoli than other battles or fronts with over half believing, incorrectly, that more New Zealanders were killed there than on any other front.[6]

Government Support for the Centenary↑

The New Zealand government committed itself to a major programme of funding the centenary. An organisation to promote and fund the centenary, operating under the brand WW100, was established in 2012 with funding from the New Zealand Defence Force, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade, the Department of Internal Affairs and Manatū Taonga, the Ministry of Culture and Heritage, where the unit was based. While WW100’s primary objectives were to “deepen understanding of the First World War” and commemorate the “service and sacrifice” of New Zealanders, knowledge alone was not sufficient. WW100 had particular ambitions: expressing a nationalist drive, the organisation sought to support activities that reflected “New Zealand’s unique culture and identity”; and – with a 21st century awareness of modern geopolitics – there was a desire to highlight “New Zealand’s enduring commitment to peace, global security and international cooperation” and to strengthen “New Zealand’s bilateral relationships with Australia and all other participants in the First World War”. Even more significantly, WW100 committed itself to “telling and preserving stories about New Zealanders’ war experiences at home and abroad”.[7] This emphasis upon individual stories became very important to the whole centenary.

In pursuit of these aims, WW100 provided three forms of support:

- The direct funding of a small number of high profile “legacy” projects. These included the development of Pukeahu National War Memorial Park, which was established by tunnelling an existing highway in the area in front of the National War Memorial Carillon in Wellington[8]; a Great War exhibition which was created in the old national museum building behind the memorial park; Ngā Tapuwae, a series of trails available as an app on cell-phones which introduced the story of the New Zealanders’ war experiences at major battle sites in Gallipoli and the Western Front and at bases and hospitals in the United Kingdom; and an enriched Online Cenotaph database which provides the records of individual soldiers in all foreign wars.[9]

- Grants funded through the Lottery Grants Board to assist community commemorative projects. 25 million New Zealand dollars were given out in 199 grants to community organisations.[10] The grants provided assistance, but did not cover the full cost of projects.

- Direct promotion of commemorative activities by listing every event or project on the WW100 website and allowing use of its distinctive stylised poppy logo, which was widely worn as a badge at remembrance events.

In addition to the dedicated support of WW100, much public funding went towards the commemoration of the war through the baselines of various government departments. This included the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (Te Papa), which supported an ambitious exhibition on Gallipoli; the National Library, which prepared some relevant exhibits; and a series of official publications which received support from the Manatū Taonga, the Ministry of Culture and Heritage, Massey University, and the New Zealand Defence Force. Creative New Zealand, the agency which provides support for cultural projects, set aside 1.5 million dollars for grants for art works and performances, and New Zealand on Air provided 13.6 million dollars for radio and television programmes.[11] Local authorities throughout the country also gave encouragement and funding to many local initiatives. What did this impressive level of support manage to accomplish during the centenary? The following analysis is largely derived from the listing of projects on the WW100 website.

Publications↑

Official History↑

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry of Culture and Heritage, the New Zealand Defence Force, and Massey University combined to develop a series of official books on the New Zealand experience in the First World War. The “Centenary History of New Zealand and the First World War” project recognised the inaccessible nature of the official histories produced in the 1920s and sought to fill gaps in the story where other publications had not appeared. Therefore, because there were excellent works on the New Zealanders at Gallipoli and in the Middle East, there were no volumes on these theatres, although one on New Zealand’s war against the Ottoman Empire is promised. By late 2019, eleven of the thirteen volumes had been published. They included a general history, very richly illustrated, on New Zealand and the First World War by Damien Fenton;[12] a comprehensive and definitive study by Ian McGibbon of New Zealand’s Western Front Campaign;[13] an extensive volume by Glyn Harper about the experience of the New Zealand soldier, Johnny Enzed;[14] and a wide-ranging work on Māori in the war by Monty Soutar.[15] There were also volumes on medical services and hospital ships,[16] one on New Zealand airmen[17] and an inventive work on the physical heritage of the Great War within New Zealand.[18] A volume on the Home Front has helped fill a major gap in the documentation of New Zealand’s First World War experience.[19]

Military History↑

These official publications were supported by a number of other works, notably on Passchendaele[20], and Le Quesnoy[21], which effectively meant that the centenary finally completed the task of providing accurate, scholarly coverage of New Zealand’s military history in the war.

Special Groups↑

Several publications highlighted the contribution of groups who had not previously been given much credit for their contribution to the war effort. These included women, who were given due recognition for their overseas service, particularly as nurses.[22] The role of women at home in raising funds and providing emotional support remained insufficiently documented, however. There were several books on the training camps, and the contribution of Pacific soldiers to the Māori contingent at last received some coverage.[23]

Culture↑

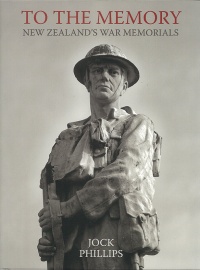

An area of the war experience which received new and welcome treatment was culture during the war. This included works on the music of the war, the war artists, and war writing.[24] There were books on photographing and filming the war.[25] There was an updated comprehensive study of New Zealand war memorials.[26] In a creative project, Kirstie Ross and Kate Hunter documented some of the personal stories associated with material culture of the war,[27] while the cultural response of soldiers in the United Kingdom received attention.[28]

Memoirs and Individual Stories↑

Both in terms of the number of publications and perhaps their impact on general understanding, the two types of books which stood out were memoirs or individual stories, and treatments of the war within a local community. A number of the individual stories were reprints of notable personal memoirs which had received little attention when first issued in the 1920s and 30s. They included Alexander Aitken’s (1895-1967) powerful Gallipoli to the Somme.[29] There were a few biographies of notable officers such as Alexander Godley (1867-1957) and William Malone (1859-1915).[30] Most common were collections of letters or diaries from ordinary “footsloggers”, often issued by family members.[31] There was little attempt in such publications to glorify the soldiers or turn them into heroes. The pains, sufferings, and sadness of war came through powerfully, including in Josh Scadden’s 2018 Broken Branches, which tells the story of those families who lost three or more sons.[32]

Community Stories↑

There were at least fifteen books, often produced and published locally, which documented the impact of the war upon a small community. Some of these told the stories of men from one district; others focused on the way the war affected the lives of those left behind. It was notable that none of these collections of stories emerged from the large cities. They were more characteristically centred on largely rural districts or small towns.[33]

Children’s Books↑

Finally, there were over half a dozen children’s books published during the centenary years which sought to bring the experience of war home to young New Zealanders. Their number suggests the major impact of books produced during the centenary was to engage people outside the academic community rather than to heighten scholars’ knowledge. Interestingly, a prolific author of children’s books concerned with the First World War was also a productive writer of military history, Glyn Harper.[34]

Digital Publications↑

The centenary of the First World War occurred at a time when the digital revolution enabled a level of access and engagement difficult to imagine at the 75th anniversary. The resources of the internet were used extensively to heighten awareness about the war. The WW100 programme made its website the primary way of communicating about the commemoration, with full coverage of activities and projects. The website also linked to its own Twitter feed and Facebook page; and to an excellent collection of historical articles about the war which was hosted on the Ministry of Culture and Heritage’s New Zealand History site.[35]

Two of the major legacy projects took digital form: the Ngā Tapuwae app of trails around World War I sites,[36] and the Online Cenotaph hosted by Auckland Museum.[37] The cenotaph not only included information about every person who had served, but also some photographs of the individual soldiers and links to base records information. The base records were digitised in a major joint Australia/New Zealand centenary project by Archives New Zealand. This site made searching for the details of individual soldiers much easier and greatly facilitated the many efforts to tell individual and community stories.

There were a number of national digital projects with a particular focus. They included a project by the New Zealand Geographic Board to tell the stories of place names with a First World War connection;[38] a photographic archive of the war graves of New Zealanders promoted by the New Zealand War Graves Trust;[39] and a website, All that Remains, produced by Te Papa, which was an online exhibition of 225 objects from the war with their stories.[40] Particular groups received attention with web-based exhibitions covering Methodists,[41] Canterbury conscientious objectors,[42] military nurses[43] and lawyers in the war.[44] But the most common web projects were those which provided databases, or stories and photographs about the war experiences of local people. A few such projects involved digitising collections of letters or photographs, such as in Whakatāne and Invercargill.[45] The National Library digitised 247 diaries or collections of letters.[46] More commonly, they took the form of databases or collections telling the stories of local individuals, such as those on Nelson Anglicans or Taupō people.[47] At least a dozen such projects were listed on the WW100 site. The final survey on the centenary suggested that 41 percent of New Zealanders aged fifteen or over had looked up information about the First World War online.[48]

Conferences↑

Immediately before the centenary, two conferences kicked off deeper consideration of the war – the University of Canterbury and Canterbury Museum sponsored a conference on “Endurance and the First World War”;[49] and the Stout Research Centre organised “Rethinking the War”. During the centenary, the Stout Centre, with the Labour History Project, sponsored a conference on “Dissent and the First World War”. Two other conferences reflected on the legacy of the war. In April 2017, an international, multidisciplinary symposium, “The Myriad Faces of War. 1917 and its Legacy”, examined this single year and the significant global impact of the First World War.[50]Canterbury 100, a collaborative project coordinated by the region’s major cultural and heritage institutions to tell the stories of the region during the war, hosted the conference “Reflections on the Commemoration of World War One” in November 2018.

Exhibitions↑

National Exhibitions↑

Undoubtedly, the form of centenary activity which reached the largest number of New Zealanders was exhibitions in museums and galleries. Indeed, the WW100 site listed more than 150 exhibitions about the First World War held in New Zealand between 2014 and 2018. Of these, about twenty-five had national themes.

By far the most popular exhibition – in terms of visitor numbers – was Gallipoli. The Scale of Our War, an exhibition about New Zealand’s involvement in the Dardanelles campaign (1915-1916) held at Te Papa. It was developed in association with Sir Richard Taylor of Weta Workshop, a New Zealand special effects and prop company. By the end of February 2019, it had attracted almost 2.5 million visitors, and had become the most visited museum exhibition in New Zealand history.[51] By the end of the centenary period, 30 percent of New Zealanders aged fifteen or over had attended it.[52]

The exhibition, which presented one of New Zealand’s foundational myths – as both memorial and spectacle – featured highly realistic, 2.4 times life-size figures, which suggested immediately that the intention was to imbue the New Zealanders at Gallipoli with heroic status. This was in part true, and certain individuals, such as Colonel Malone who commanded the Wellington Regiment were presented in this manner. However, the Gallipoli exhibition development team, including its creative director, Taylor, decided that instead of focusing on commanders they would employ “diversifying criteria” in their selection of the giant figures who represent a “broad cross section of human experiences” as well as the original “cast” at Gallipoli, including officers and ranks, an army doctor and nurse, Pākehā and Māori, young and mature. Crucially, individuals “who could act as emotional gateways to the ‘action-packed’ thematic episodes” were selected.[53]

Two of the “eight ordinary New Zealanders who found themselves in extraordinary circumstances” immortalized in the Gallipoli exhibition were Private Rikihana Carkeek (1890-1963), from Ngāti Raukawa and Corporal Friday Hawkins (1891-1968), from Ngāti Kahungunu. Both, who were depicted determinedly firing their machine gun at the opposing Turks, fought at Gallipoli with the Māori contingent. While the number of New Zealanders who served on Gallipoli is disputed amongst historians, the currently most accepted number is between 16,000 and 18,000, of which 500 served in the Māori contingent. This does not include the considerable number of New Zealanders who served with the Australian forces.

On the basis of these figures alone, the number of Māori soldiers represented was disproportionate. The authors agree that just as it has been valid to shift the focus from Gallipoli to the Western Front to tell a more balanced and accurate story of New Zealand’s involvement in the war, so too is it important to highlight the previously downplayed Māori contribution to the First World War.

Other figures in New Zealand’s First World War story who have – until recently – been largely disregarded were soldiers who received the death penalty, such as John Robert “Jack” Dunn (1888-1915), a private who had been suffering from dysentery. He fell asleep on guard duty and was court-martialled and sentenced to death. Eventually, the sentence was rescinded but Dunn died three days later in the attack on Chunuk Bair. Also presented was Charlotte Le Gallais (1881-1956), a nurse on the hospital ship Maheno, who came to Gallipoli in a vain search for her brother, and Percival Fenwick (1870-1958), a doctor whose story illuminated the ghastly nature of the injuries suffered on the peninsula.

It was unlikely that visitors to this “hybrid offspring of the movie and museum worlds” would come away from the exhibition without a powerful sense of the gruesome horrors of war and an intended emotionally-charged response. Additionally, despite the government’s best intentions to deflect public attention away from Gallipoli after the 2015 centenary, if anything, the exhibition’s success cemented the Dardanelles campaign at the centre of New Zealand’s First World War story.

Just up the road in Wellington was another major national exhibition, The Great War Exhibition, which was held at the site of the old Dominion Museum and National Art Gallery just behind Pukeahu National War Memorial Park. 21 percent of New Zealanders aged fifteen or over attended it.[54] The originator was the film-maker Sir Peter Jackson, who not only has a deep and longstanding interest in the First World War – in part because of his grandfather William Jackson's (1892-1940) wartime experience – but also a remarkable collection of artefacts which formed the basis of the exhibition. There were some refreshing aspects of this exhibit; it placed the war in an international context with a series of “sets” located in Europe; and there was much use of old photographs which had been digitally colourised to give them a powerful sense of realism and empathy with the soldiers of a century ago. In temporary exhibitions and public talks, The Great War Exhibition also broached subjects which mainstream exhibitions had either shied away from or decided not to prioritise, including: neutrality, profiteering, war experiences of women at home and abroad, war in the Sinai and Palestine, the service of Chinese and Indian New Zealanders in the First World War, dissent, and the wounded. One major feature, the “Quinn’s Post” trench experience, was significantly delayed and despite the popularity of the adjacent memorial park, attendance at the exhibition lagged, particularly once entry charges were imposed.

Other museums with a military mandate, as might be expected, developed special centenary exhibitions. The Auckland War Memorial Museum developed a series of exhibitions ranging from one on the home front to a Gallipoli Minecraft exhibit and an interactive gallery, Pou Kanohi, which presented the war for younger visitors. The National Army Museum also developed a number of special exhibitions – such as those on the tunnellers, and another on the capture of Le Quesnoy by the New Zealand Division in the last week of the war. Special interest museums naturally took up the theme. The New Zealand Portrait Gallery showed portraits of people associated with the war. The Rugby Museum in Palmerston North and the Cricket Museum in Wellington explored sportspeople who participated in the war. There were a number of exhibitions which travelled the country from overseas sources: a collection of photographs about Gallipoli from Turkey, which was one of the few exhibits that gave prominence to “the other side”; and a wide-ranging exhibition from Australia on the experiences of New Zealand and Australian women.

Local Exhibitions↑

The National Army Museum also developed Heartlanders of World War One, a popular touring exhibit, which travelled to some twenty-five locations. This told the stories of people from rural and small-town New Zealand under the tag-line, “Getting to Know the Locals”. That title was indeed the theme of by far the greatest number of museum displays during the centenary. On the WW100 site there were about eighty exhibitions primarily dedicated to telling local stories. Many recounted the experiences of soldiers from a particular location – Raglan Museum told about 154 Raglan soldiers, and the exhibit included descendants reading letters and diary entries from the battlefields; the Greerton Library focused on four Tauranga men who died at Passchendaele; Te Awamutu Museum presented seven stories of Waikato-Maniapoto Māori who fought. Sometimes an individual soldier was the focus – Nelson Museum’s “In Search of a Family History” told of the Gallipoli ordeal of John Robert Dunn; Otago Museum explored the battlefield recollections of its former director, Henry Devenish Skinner (1886-1978); Aratoi Museum in Masterton remembered the medical services of Norman Prior (1882-1967). Other exhibits told about the impact of war on the local community, such as Papakura’s display on the home front or Taupō’s on what life was like in Taupō during the war. Many of these exhibitions were “from little towns in a far land” to quote the title of the north Otago exhibition; but even the cities went local. Toitū, the Otago Early Settlers Museum, devoted much space and energy to telling the story of the Otago Regiment and Dunedin’s response to the war; Canterbury Museum had a large display on Canterbury and World War One. Lives Lost, Lives Changed. A few of the local exhibitions emphasised groups normally given little attention. The Wellington Public Library had a display about Sikh soldiers, while Māori participation was emphasised in the exhibitions at the Hastings War Memorial Library and the Paekākāriki Station Museum, in addition to the Te Awamutu display. The story of the 150 Niuean volunteers was the focus of an exhibit in Ōtara. Women’s contributions during the war came in for some attention – the Otago Museum told the story of three local nurses, while across town, Toitū developed a display entitled Women’s War.[55] The final survey of New Zealanders aged fifteen or above showed that during the centenary period 71 percent had visited a museum or gallery exhibition about the First World War.[56]

Local Art Exhibitions↑

The WW100 site listed over forty displays of artwork which reflected on the First World War. Some were pieces by very well-known artists – Stanley Palmer remembered Gallipoli at the art gallery in Blenheim, Max Gimblett installed a memorial artwork at St David’s church in Auckland; Michael Parekowhai exhibited four flower photographs to commemorate the soldiers of the Maori Pioneer Battalion who died on European battlefields. A very popular touring exhibition was Laurence Aberhart’s photographs of New Zealand war memorials.

There were also collaborative art works involving the contributions of many. These included Flowers of War, a collaborative wreath at Canterbury Museum; a collection of sweetheart pin cushions for each soldier who died from the Upper Clutha district; and fourteen quilted samplers to commemorate the war at Gisborne’s Tairāwhiti Museum. Both the National Army Museum and the Air Force Museum displayed thousands of hand-crafted poppies (mostly by women). There were also anti-war or anti-militarism gestures – from a group of “fringe outsider artists” who took it upon themselves to “declare war on war” at a studio in Auckland, and Wellington Peace Action carried out a “guerrilla” action placing figurative sculptures commemorating conscientious objectors in prominent positions around the city on Anzac Day 2016 (including close to Te Papa). In Auckland, the Cook Islands community paid tribute to the 500 soldiers from Rarotonga who served. UK-based New Zealander Cat Auburn’s 2016 work in for SCAPE Public Art in Christchurch, The Horses Stayed Behind, memorialised the 10,000 horses that left New Zealand for the front lines in the First World War in 500 flower rosettes crafted from horse hair.[57] Any neutral observer cannot but be impressed by the energy and creativity of many New Zealanders, particularly women, who were intent on “Remembering Anzac in stitch”, to quote the title of the Tauranga Embroiderers’ Guild exhibition.

Moving Images↑

The number of film and television projects was not huge, but they were significant and widely viewed. Indeed, the final survey of the New Zealand public aged fifteen or above showed that 58 percent had watched a television documentary about the war during the centenary.[58]When We Go To War (2015), a fictional, drama mini-series in six one-hour episodes, commissioned and broadcast by TVNZ, depicted the war’s impact at home as well as on the soldiers at Gallipoli and Egypt. It averaged about 300,000 viewers per episode. Also on television, there were six series of “Great War Stories” which played on the channel Three’s evening news. These five-minute stories nearly always told the war through the eyes of one participant. The Prime channel showed “War News”, a mockumentary style presentation about the major events of the war involving New Zealanders. Māori Television continued to put a large investment into covering Anzac Day during the centenary, and in 2015 showed an Australian-New Zealand production, “Anzac Tides of Blood”. The presenter, New Zealand actor Sam Neill, approached the “enduring myth of Anzac” and Gallipoli through his family’s military tradition and “look[ed] for answers as to why that particular event has become symbolic and is remembered more than any other in the two nations’ shared history.” Neill’s viewpoint, “I hate militarism, loathe nationalism but honour those who served”, would probably find sympathy with many contemporary New Zealanders.[59]

There were only two full-length feature films – 25 April, a graphic novel-style animation using material from the letters, diaries, and memoirs of six individuals who experienced the Gallipoli campaign; and Peter Jackson’s They Shall Not Grow Old funded by British money and using mainly British sources – oral histories and old film footage – to present, out of jerky black and white footage, a smooth colourised documentary with atmospheric sound which made the experience of joining up and enduring the ordeal of the Western Front immediate.[60] New Zealand also saw repeat screenings of old classics like Gallipoli and All Quiet on the Western Front and Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision (New Zealand Archive of Film, Television and Sound) put together For King and Country. New Zealand’s First World War on Film. This collection enjoyed many screenings around the country.

Several of the war-related exhibitions also developed a film component. The most ambitious was Toitū Otago Settlers Museum, a regional history museum in Dunedin, which produced a series of films covering the “Journey of the Otagos”. This detailed the experiences and engagements of the Otago Regiment on both Gallipoli and the Western Front. The Museum of Wellington prepared a short film on Field Punishment Number One, which was a reworking in film of the artist Bob Kerr’s powerful paintings about the treatment of conscientious objectors.[61]

Concerts and Performances↑

With support from Creative New Zealand available, it was unsurprising that the centenary saw a number of relevant musical and dramatic performances. Indeed, 26 percent of the population aged fifteen and over attended a cultural performance about the war.[62] The centenary of Gallipoli in 2015 saw a play by Geoff Allen, “Sister Anzac”, concerned with the experiences of nurses on New Zealand’s first hospital ship, Maheno, which was stationed off Anzac Cove at Gallipoli. Dave Armstrong’s Anzac Eve (2015) played out a debate between two Kiwi men and two Aussie women “on their big OE” setting up camp at Anzac Cove the night before dawn commemorations, which was a similar theme to Ralph McCubbin Howell’s Dead Men’s Wars (2015), a joint Australia/New Zealand production. The European theatre of war was acknowledged in Philip Braithwaite’s The War Play (2015) about his great uncle, who was shot for his alleged role in a mutiny in the north of France. An Awfully Big Adventure (2014), written and directed by Leo Gene Peters, aimed to reach young people with vaudeville-style music; there was a co-production by Hleb Teatar (Serbia) and Akeake Theatre called Sisters in Arms (2014) about a Canterbury female surgeon in Serbia; and Jan Bolwell’s very personal solo play Bill Massey’s Tourists (2017) recounted the war experience of her grandfather. Circa Theatre’s All our Sons (2015) by Witi Ihimaera told a story of divided loyalties in a Māori family during the war. While her son and two grandsons join up, a grandmother objects to them fighting alongside the enemy, Pākehā (European New Zealanders).[63]

The First World War was the subject of several notable dance works. For their touring special programme of works to mark the centenary of World War I, Salute, the Royal New Zealand Ballet collaborated with the New Zealand Army Band and New Zealand composers and choreographers Dwayne Bloomfield, Gareth Farr, Neil Ieremia and Andrew Simmons.[64]

Arts Laureate Shonagh McCullagh drew on the story of her great uncle who died on the Somme and her great grandfather who returned from Gallipoli and the Somme a greatly changed man to choreograph Rotunda. This was presented by the New Zealand Dance Company in both New Zealand and Australia, accompanied by contemporary brass music from New Zealand composers including Gareth Farr, John Ritchie, John Psathas, and Don McGlashan. Another arts laureate, Lemi Ponifasio, and his MAU company, used Pacific dance to explore the war in I am (2014).[65]

The 2018 World of Wearable Arts gave its supreme award to WAR sTOrY, designed by Natasha English and Tatyanna Meharry. Their costume, made from recycled materials, paid a tribute to those New Zealanders who served and died in the war.

In music too, the centenary attracted some impressive work. John Psathas’s No Man’s Land (2016), a multi-media cinematic symphony reflecting on the devastating impact and futility of war, included 150 live and virtual musicians from opposing forces of the First World War performing as “one global orchestra”. The noted composer Gareth Farr, who lost three great-great uncles on the French front, composed Relict Furies (2014) which gave a voice to those women, both wives and sweethearts, who lost their loves to the maelstrom of the war. It played to great acclaim at both the Edinburgh and New Zealand international festivals. He also wrote a cello concerto, Chemin de Dames, to mark the centenary in 2017 of one of the war’s bloodiest battles. Anthony Ritchie’s choral work, Gallipoli to the Somme (2015), was performed and well received both in New Zealand and in the United Kingdom. It followed the individual story of one soldier, Alexander Aitken, and was based on his memoir of the same title. Michael William’s Letters from the Front (2015) symphony, commissioned for the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra (NZSO) for the commemoration of the First World War, was based on soldiers’ letters including one by his great grandfather, who was killed at Passchendaele in 1917. In April 2018, both the Auckland Philharmonia and the BBC Orchestra in London performed Face, a collaboration between the composer Ross Harris and the poet and novelist Vincent O’Sullivan, which featured a choir and three vocal soloists. It was based on the story of the New Zealand surgeon, Harold Gillies (1882-1960), who pioneered facial reconstruction in World War I. O’Sullivan and Harris considered this story a meaningful way to end the centenary; because for men suffering such injuries, “there’s no conclusion to the war. There is no armistice. For the rest of their lives, they lived with the day of that injury.”[66]

For other musicians, however, the exact end of the war, the armistice, was remembered by concerts. In over a dozen communities throughout the country, 11 November 2018 was marked by concerts – orchestras, choirs, and brass bands brought the centenary to a close.

Memorials↑

Pukeahu National War Memorial Park↑

In the years following World War I, communities around New Zealand erected memorials and honours boards so that those who had died in the war would not be forgotten. It was natural, therefore, that the centenary saw a remarkable revival of this memorializing drive. 60 perent of New Zealanders aged fifteen and over visited a First World War memorial during the centenary.[67] In the nation’s capital, Wellington, the prestige of the National War Memorial in the form of a carillon and a Hall of Memories had long been diminished by the existence of a main highway passing directly in front. A major centenary project – which cost 120 million dollars – was to place the road in a tunnel, appropriately named Arras Tunnel in memory of the New Zealand Tunnellers at Arras during the First World War, and to create a memorial park above the tunnel.[68] This was intended to be the site of monuments contributed by other countries, referring to their relationships, which were in large part built through war. The first, the Australian memorial, built of rich red pillars of stone reminiscent of Australia’s red centre, was opened in April 2015. Before the centenary was over, additional memorials had been contributed by the United Kingdom, France, Turkey, Belgium and the United States. Instead of stone and metal, Germany offered a unique and powerful memorial tapestry, Flandern (Flanders) by artist Stephan Schenk, as a symbol of reconciliation. This was subsequently gifted to parliament. The dedication of memorials in the park involved high-level dignitaries, reflecting the important role played by remembrance – especially among allies – in international relations.

In 2015, New Zealanders commemorated the centenary of the Anzac landing at Gallipoli at Pukeahu National Memorial Park as a key foundational story in the country’s national identity.[69] Although an “official” government memorial acknowledging conflict within the land has yet to be built, the use of the original Māori name of the hill, Pukeahu, in the title of the new memorial park, and the symbolism of the Tangata Whenua Gardens, represent a restoration of sorts in New Zealand’s emerging national memorial landscape and a reflection of changing cultural dynamics.

The new garden reflects the long association of Māori with Pukeahu, and a bronze sculpture, Hinerangi, created by Māori artist Darcy Nicholas, conflates past conflicts at home and overseas, inserting as yet untold stories of “civil war” into the nation’s narrative of remembrance.

New Memorials↑

The centenary was an opportunity for many communities to provide for memorials where none previously existed or to honour new groups and individuals. There were nineteen new memorials which received funds from the Lottery Grants Board.[70] Some of the new memorials were put up in places which had few residents in the years of the First World War and wanted a location for 21st century citizens to hold an Anzac Day service. These included Papamoa, Te Kauwhata, and the Mangapurua and Kaiwhakauka valleys in King Country. To highlight the significance of the Featherston Military Training Camp – New Zealand’s largest military camp – in local and national history, and to remember the 60,000 men who trained there, a memorial designed by Paul Dibble was installed in the town of Featherston in November 2018. On top of the neighbouring hill was placed a tribute to the famous “Rimutaka crossing” to Trentham camp, which recruits had to experience before leaving for war.

Other communities erected memorials to groups who had previously not been recognised for their war service. These included a new memorial to the tunnellers at the mining town of Waihi, and a statue to the famous war artist Horace Moore-Jones (1868-1922) in Hamilton, which also put up a memorial to the horses which served in the war. ŌtakiCollege memorialised the sinking of SS Ōtaki in 1917, and, in 2014, Fairlie put up a statue by Donald Paterson of a young soldier leaving for war at the local railway station. The Archibald Baxter Memorial Trust was established in Dunedin to build a sculpture garden where visitors could reflect on the experience of Archibald Baxter (1881-1970) and other conscientious objectors from New Zealand and their reasons for rejecting war; organize an annual peace lecture; and promote an essay competition in Otago schools on the topic of peace.[71]

There was also considerable planting of memorial trees or avenues, following a tradition established after the war, when individual trees served as surrogate headstones. There was an avenue from Waddington to Sheffield in Canterbury, a memorial tree walk in Blenheim, a memorial forest in Coromandel, and on Anzac Day 2018 the government announced a plan, Matariki Tu Rākau, which envisaged the planting of 350,000 trees over the next two years to honour New Zealand service people and mark the armistice of the war.

The Places of Remembrance project sought to bring attention to streets named after people from the war by adding an Anzac poppy flower to street signs.[72]

Refreshed Memorials↑

The National War Memorial’s art deco carillon tower and Hall of Memories underwent a seismic upgrade and occupational health and safety and heritage retrofit during the centenary period, which was completed in 2015. After four years of restoration work the carillon’s seventy-four bells were heard again in May 2018.[73]

The public attention which the centenary brought to local memorials naturally produced a drive to improve and restore them. Quite a few communities did research and discovered several names to be added to existing monuments. Nelson added no fewer than seventy-eight names. Others added new panels to old memorials. At least thirty-six communities listed the restoration and re-lettering of their war memorial on the WW100 projects page; but one suspects the extent of restoration was much larger.[74] An unusual refreshed memorial was the restoration at Paekākāriki of the “Passchendaele” steam locomotive.

Overseas Memorials, Commemorations, and Art Works↑

Many New Zealanders undertook their own commemorative acts by travelling as individuals, families or in guided tours to commemorate the experiences of their ancestors “from the uttermost ends of the earth” 100 years ago. Perhaps there is no substitute for what Françoise Choay describes as the “weight of the real”, being in the place where the terrible events we remember actually happened, instead of standing before a far-removed monumental surrogate.[75]

New Zealanders also contributed towards memorials honouring their countrymen who had served at overseas sites. In April 1917, The Earth Remembers, a bronze memorial sculpture by Marian Fountain was unveiled at Carrière Wellington, the Wellington Quarry Museum in Arras, France. In addition, memorial gardens were created with New Zealand support at Passchendaele and Le Quesnoy. The latter, the New Zealand Peace Garden, Rangimarie, was opened by the New Zealand governor-general, Her Excellency The Right Honourable Dame Patsy Reddy, on 3 November 2018, the day before the centenary of the town’s liberation. The New Zealand-based Passchendaele Society commissioned landscape architect Cathy Challinor to design the New Zealand Memorial Garden at Passchendaele, Nga Pua Mahara – Petals of Remembrance, commemorating the 100th anniversary of the 1917 battle.[76] On Anzac Day 2019, the garden was enhanced by an 8 metre tall pou maumahara carved by students from the Māori Arts and Crafts Institute at Rotorua.

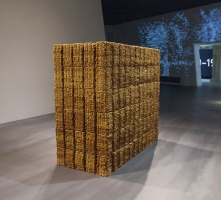

After touring eight locations in New Zealand, Helen Pollock’s Victory Medal sculpture travelled overseas to be exhibited in Arras surrounded by a field of “poppies” (red discs) with commemorative messages designed by Tony McNeight. This installation, Le Coquelicot de Paix, was unveiled on the centenary of the Battle of Arras. The sculpture found a permanent home in the grounds of the New Zealand War Memorial Museum in Le Quesnoy, opened on the day of the centenary of the town’s liberation. Another overseas sculpture, this time containing explicitly New Zealand-themed content was Kingsley Baird’s Stela installation at the German Federal Armed Forces Militärhistorisches Museum in Dresden. Baird’s “memorial” sculpture comprised 18,000 Anzac biscuits in the form of soldiers from the First World War that were consumed by museum visitors over the course of the exhibition.

Events and Other Projects↑

Anzac Day 2015↑

From 1916, New Zealanders, like Australians, had commemorated the landing of troops on Gallipoli beaches, on 25 April each year and in 1921, the day had become a public holiday. The centenary of the day in 2015 was, not surprisingly, the most attended of all Anzac Days in New Zealand history. The dawn service at Auckland Domain attracted at least 25,000 people, the same number as were estimated at Wellington’s new Pukeahu National Memorial Park. Even smaller centres attracted record numbers – Dunedin 20,000, Whāngārei 9,000 and even 2,000 at Ashburton, which was about 10 percent of its population.[77] Although numbers dropped in the later years of the centenary, they were consistently higher than before 2015.

Sound and Light Shows↑

In many communities, the local war memorial was embellished with other acts of remembrance. In Wellington, in the week of Anzac Day 2015, a sound and light show commissioned by the Wellington City Council, WWI Remembered. A Light and Sound Show, comprised images of the history of the First World War projected onto the face of the carillon and the old Dominion Museum and National Art Gallery building. Thousands attended each evening. Featured strongly was Māori imagery by Māori artist Ngataiharuru Taepa, claiming a place for the nation’s indigenous culture in New Zealand’s war commemoration, albeit a transitory one.

Later that year, Appleton Park hosted Remembrance, a temporary installation created by international art and design collective Squidsoup, composed of 860 lights moving in the wind, representing those from the Wellington region who died at Gallipoli.[78] The armistice was the occasion for light shows playing on the face of the Auckland War Memorial Museum, and at both Hokitika and Cambridge.

Fields of Remembrance↑

The centenary of the armistice saw “fields of remembrance” set out in front of war memorials in many communities, both on Anzac Day and then, more commonly, around Armistice Day. These were local initiatives but were supported by a charitable trust which included the Royal New Zealand Returned Services Association. Fields were set out in provincial cities like Timaru, Hamilton and Whāngārei, but also the larger centres. In Auckland, 18,277 named white crosses, one for every New Zealander who died in the war, were positioned in front of the cenotaph and war memorial museum. Christchurch had 4,300 named crosses in Cranmer Square representing Cantabrians who died, and Dunedin saw 3,988 (the numbers from Otago and Southland) in front of the Cenotaph. In each case, a family member was invited to collect the cross with the name of their ancestor. In Wellington, a field of remembrance, with a cross for every fallen Wellingtonian, 5,270 in number, was set up in the Botanic Gardens in April/May 2018. The initiative for these fields came from the Fields of Remembrance Trust, which also sent packs of crosses to schools throughout the country.[79] 38 percent of New Zealanders aged fifteen or above visited a field of remembrance during the centenary.[80]

There were many other events marking the centenary around the country – lectures, poetry readings, and bus tours to war memorials. New Zealand Post had a five-year programme of commemorative stamps, one set for each year of the war from 2014-2018.

Centenary of the Armistice↑

The centenary of the war climaxed with armistice commemorations on 11 November 2018. These were notable for much use of dance and music, both at ceremonies around the war memorials and at separate concerts in the evening. The national armistice ceremony in front of the National War Memorial Carillon saw speeches from the governor-general and Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern, a number of Māori waiata and a moving dance performance which referred both to the pain of wartime losses and the joy of the coming of peace. As with other ceremonies on that day, it climaxed with a “roaring chorus” of thanksgiving. It was noteworthy that military ritual played almost no part in the ceremony.

Conclusion↑

There can be little doubt that the centenary of the First World War in New Zealand increased knowledge and understanding about that war. Professional historians filled in gaps in knowledge, continuing a process which had begun in the decade before the centenary.

More significantly, knowledge was spread deeper into the community. In the final survey on the centenary programme, the percentage of those aged fifteen and above with at least a reasonable knowledge of the war had increased from 2012 by 4 percent to 83 percent, and the proportion those with a good understanding had risen from 31 percent to 39 percent.[81] This was not dramatic, and far more people still believed that Gallipoli saw the highest number of New Zealand deaths, although those naming the Western Front had increased from 17 percent in 2012 to 26 percent in 2018.[82] To the extent that knowledge of the war improved, it came about in large part because the centenary managed to bring the huge story of the war down to a personal level. Many of the books, exhibitions, television programmes, even plays, concerts and dance works focused on the war stories of particular people. Many New Zealanders entered into an understanding of the war by finding out about their own ancestors, and digitized databases made this easier. Families carried home their white crosses with humility and sadness. During the centenary, 23 percent of New Zealanders (aged fifteen or above) looked into their family involvement.[83] In addition, the exhibitions, books and local events made the immensity of the war count within local communities. Small towns and rural districts, suburbs of cities began to learn about the war’s impact among the places around them. It was noteworthy that this awakening to the past occurred not just among older people but among children who participated in events and read books specifically aimed at their age groups. It is important to appreciate that to a certain extent the commemorations reflected a “bottom up movement” driven by communities themselves, while also being significantly enabled by government facilitation and support.

The centenary served to highlight a number of sub-groups who had received little attention previously. The role of women received good attention in most of the media used, although more still needed to be said about their central place on the home front. How far women were particularly affected by the centenary is unknown because the final WW100 survey did not analyse gender. There were good books and exhibitions about minorities like Sikhs and Pacific Islanders. Stories of Māori soldiers were given prominence in exhibitions, a few books and television programmes, and Māori ritual played a major role in the ritual of ceremonies during the centenary. In addition, the thousands of New Zealand horses who went overseas were honoured.

One must be impressed by the creativity and range of media used by New Zealanders during the centenary, and by the helpful support given by the WW100 programme. In general, the portrayal of the New Zealand soldiers was as victims rather than heroes. The final report found that the most widespread feeling about the war was sadness.[84] There was little effort to glorify their achievements, but there was a recognition of their sacrifice and bravery in hard times. If there was a striking absence in the coverage, it was that the long-term impact of the war experience upon the returned men and their families remained largely unexplored, in part because of the absence of extensive repatriation records. The New Zealand exhibitions and books lacked a deep investigation of the medical and psychological torments which often afflicted returned men in the 1920s and 30s, as occurred more often during the centenary in Australia. David Hastings approached this story in his book, The Unknown Anzac, which dealt with a soldier who essentially suffered a major life-changing mental breakdown.[85] But this was unusual. The burdens which women and children carried at home both during the war when their loved ones were overseas and even more after they returned remain, too, little understood. One can but hope that the end of the war’s centenary will not mean the end of telling New Zealanders the full unvarnished story about the nation’s greatest trauma of the 20th century.

Jock Phillips, Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand

Kingsley Baird, Massey University

Section Editor: Bruce Scates

Notes

- ↑ About WW100, issued by WW100 – New Zealand’s Centenary Programme Ran from 2014 to 2019, online: https://ww100.govt.nz/about (retrieved: 18 February 2018).

- ↑ Pugsley, Christopher: Gallipoli. The New Zealand Story, Auckland 1984; Shadbolt, Maurice: Voices of Gallipoli, Auckland 1988.

- ↑ During the centenary period, New Zealand Defence Force historians John Crawford and Matthew Buck unearthed evidence to support the long-held contention by some historians that the number of New Zealand soldiers who served at Gallipoli was significantly higher than previously thought. According to Ministry for Culture and Heritage historian David Green, this evidence is significant because “Twice as many New Zealand families as previously thought have a direct link to the Dardanelles”. Green, David: How Many New Zealanders Served on Gallipoli. Some New Answers, issued by WW100 – New Zealand’s Centenary Programme Ran from 2014 to 2019, online: https://ww100.govt.nz/how-many-new-zealanders-served-on-gallipoli-some-new-answers (retrieved: 18 February 2018).

- ↑ See for example Pugsley, Christopher: The ANZAC Experience. New Zealand, Australia and Empire in the First World War, Auckland 2004; Harper, Glyn: Dark Journey, Auckland 2007; Kinloch, Terry: Devils on Horses. In the Words of the Anzacs in the Middle East, 1916-1919, Auckland 2007.

- ↑ For example, Crawford, John (ed): No Better Death. The Great War Diaries and Letters of William G. Malone, Auckland 2005.

- ↑ Benchmark Survey of the New Zealand Public’s Knowledge and Understanding of the First World War and Its Attitudes to Centenary Commemorations, issued by WW100 – New Zealand’s Centenary Programme Ran from 2014 to 2019, online: https://ww100.govt.nz/sites/default/files/files/Benchmark%20survey%204%20March%20Report%20WEB.pdf (retrieved: 3 December 2019), pp. 5, 44.

- ↑ Mission and Objectives, issued by WW100 – New Zealand’s Centenary Programme Ran from 2014 to 2019, online: https://ww100.govt.nz/mission-and-objectives (retrieved: 15 February 2019).

- ↑ A “cut-and-cover” structure enabled a section of State Highway 1 to run underground and the new memorial park to be built above. The newly created vehicle underpass was called the Arras Tunnel, referencing the excavation work undertaken by the New Zealand Tunnelling Company under the French town of Arras in 1917 in the months leading up to the Battle of Arras.

- ↑ He Toa Taumata Rau. Online Cenotaph, issued by Auckland War Memorial Museum, online: http://www.aucklandmuseum.com/war-memorial/online-cenotaph (retrieved: 15 February 2019).

- ↑ WW100. First World War Centenary Programme Final Report, April 2019, issued by WW100 – New Zealand’s Centenary Programme Ran from 2014 to 2019, online: https://ww100.govt.nz/sites/default/files/files/mch-ww100-report-ART-FINAL-WEB-RES.pdf (retrieved: 10 May 2019), pp. 8, 12.

- ↑ Collaborative Arts Projects to Mark First World War Centenary, issued by Creative NZ, online: http://www.creativenz.govt.nz/news/collaborative-arts-projects-to-mark-first-world-war-centenary (retrieved: 15 February 2019); First World War Centenary Programme Final Report, p. 12.

- ↑ Fenton, Damien: New Zealand and the First World War, 1914-1919, Auckland 2013.

- ↑ McGibbon, Ian: New Zealand’s Western Front Campaign, Auckland 2016.

- ↑ Harper, Glyn: Johnny Enzed. The New Zealand Soldier in the First World War, 1914-1918, Auckland 2015.

- ↑ Soutar, Monty: Whitiki! Whiti! Whiti! Eh!: Māori in the First World War, Auckland 2019.

- ↑ Rogers, Anna: With Them Through Hell. New Zealand Medical Services in the First World War, Auckland 2018; McLean, Gavin: The White Ships. New Zealand’s First World War Hospital Ships, Wellington 2013.

- ↑ Claasen, Adam: Fearless. The Extraordinary Untold Story of New Zealand’s Great War Airman, Auckland 2017.

- ↑ Bargas, Imelda / Shoebridge, Tim: New Zealand’s First World War Heritage, Auckland 2015.

- ↑ Loveridge, Steven / Watson, James: The Home Front. New Zealand Society and the War Effort 1914-1919, Auckland 2019.

- ↑ Macdonald, Andrew: Passchendaele. The Anatomy of a Tragedy, Auckland 2013.

- ↑ Pugsley, Christopher: Le Quesnoy 1918, Auckland 2018.

- ↑ Tolerton, Jane: Make Her Praises Heard Afar. New Zealand Women of World War One, Wellington 2017; Matthews, Kay Morris: Recovery. Women’s Overseas Service in World War One, Gisborne 2017.

- ↑ Weddell, Howard: Soldiers from the Pacific. The Story of Pacific Island Soldiers in the New Zealand Expeditionary Force in World War One, Wellington 2015; Pointer, Margaret: Niue and the Great War, Dunedin 2018.

- ↑ Bourke, Chris: Goodbye Maoriland. The Songs and Sounds of New Zealand’s Great War, Auckland 2017; Haworth, Jennifer: Behind the Twisted Wire. New Zealand Artists in World War 1, Christchurch 2016; Ricketts, Harry / McLean, Gavin (eds.): The Penguin Book of New Zealand War Writing, Auckland 2015.

- ↑ Fitzgerald, Michael / Regnault, Claire: Berry Boys. Portraits of First World War Soldiers and Families, Wellington 2014; Pugsley, Christopher: The Camera in the Crowd. Filming New Zealand in Peace and War, Auckland 2017.

- ↑ Phillips, Jock: To the Memory. New Zealand War Memorials, Nelson 2016.

- ↑ Hunter, Kate / Ross, Kirstie: Holding on to Home. New Zealand Stories and Objects of the First World War, Wellington 2014.

- ↑ Barnes, Felicity: New Zealand’s London. A Colony and Its Metropolis, Auckland 2012; Brown, Colleen: The Bulford Kiwi. The Kiwi We Left Behind, Auckland 2018.

- ↑ Aitken, Alexander: Gallipoli to the Somme. Recollections of a New Zealand Infantryman, Auckland 2018.

- ↑ Kinloch, Terry: Godley. The Man behind the Myth, Dunedin 2018; Vennell, Jock: Man of Iron. The Extraordinary Story of New Zealand WW1 Hero Lieutenant Colonel William Malone, Auckland 2015.

- ↑ For example, Fenton, Damien / Higgins, Shaun: The Anzacs. An Inside View of New Zealanders at Gallipoli, Auckland 2015; Phillips, Jock (ed.): Brothers in Arms. Gordon and Robin Harper in the Great War, Wellington 2015; Barker, Paul S. (ed.): From Geraldine to Jericho. John Barker and the Great War, Wellington 2017.

- ↑ Scadden, Josh: Broken Branches. New Zealand Families Who Lost Three or More Children in the Great War, Auckland 2018.

- ↑ For example, Leather, Graeme: The Home Front. North Otago, 1914-18, Oamaru 2014; Fletcher, Linda: Horowhenua and the Great War 1914-1918, Levin 2014.

- ↑ During the centenary period, Harper wrote four children’s books, three of which won significant awards.

- ↑ First World War History, issued by NZHistory, online: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/war/first-world-war (retrieved: 15 February 2019).

- ↑ Ngā Tapuwae Trails, issued by Ngā Tapuwae. New Zealand First World War Trails, online: https://ngatapuwae.govt.nz/ (retrieved: 15 February 2019).

- ↑ He Toa Taumata Rau. Online Cenotaph.

- ↑ WW1 Through Place Names, issued by Land Information New Zealand, online: https://www.linz.govt.nz/regulatory/place-names/ww1-through-place-names (retrieved: 15 February 2019).

- ↑ New Zealand War Graves Project, issued by New Zealand War Graves Project, online: https://www.nzwargraves.org.nz/new-zealand-war-graves-project (retrieved: 15 February 2019).

- ↑ Now defunct. A project description can be found at All That Remains. WWI Objects from New Zealand Museum Collections, issued by Museum of New Zealand. Te Papa Tongarewa, online: https://www.tepapa.govt.nz/sites/default/files/all_that_remains_info_for_participants_oct_2014.pdf (retrieved: 3 December 2019).

- ↑ Methodist Rolls of Honour and Memorial Plaques, issued by WW100 – New Zealand’s Centenary Programme Ran from 2014 to 2019, online: https://ww100.govt.nz/methodist-rolls-of-honour-and-memorial-plaques (retrieved: 15 February 2019).

- ↑ Voices Against War, issued by Voices Against War. Courage, Conviction and Conscientious Objection in WW1 Canterbury, online: http://voicesagainstwar.nz/home (retrieved: 15 February 2019).

- ↑ New Zealand Military Nursing, issued by New Zealand Military Nursing, online: http://www.nzans.org (retrieved: 15 February 2019).

- ↑ New Zealand Lawyers Roll of Honour, World War I, issued by New Zealand Law Society, online: https://www.lawsociety.org.nz/news-and-communications/people-in-the-law/new-zealand-lawyers-roll-of-honour,-world-war-i (retrieved: 15 February 2019).

- ↑ World War 1 Commemoration, issued by Whakatāne Museum and Arts, online: https://www.whakatanemuseum.org.nz/exhibitions-events/world-war-i-commemoration (retrieved: 15 February 2019); About the Project, issued by Since Writing You Last..., online: http://www.sincewritingyoulast.co.nz (retrieved: 15 February 2019).

- ↑ First World War Centenary Programme Final Report, p. 8.

- ↑ World War I Index. Nelson Anglican Centre Archive, issued by the Prow, online: http://www.theprow.org.nz/world-war-one/wwi-index (retrieved: 15 February 2019); KeteTaupo. Our WW1 Stories, issued by KeteTaupo. Our WW1 Stories, online: http://ketetaupo.peoplesnetworknz.info/en/our_ww1_stories (retrieved: 15 February 2019).

- ↑ Follow-up Survey of the New Zealand Public. To Measure the Impact of Their Experience with First World War Centenary Commemorations, issued by WW100 – New Zealand’s Centenary Programme Ran from 2014 to 2019, online: https://ww100.govt.nz/sites/default/files/files/WW100%20Final%20Survey%20full%20report%20from%20Colmar%20Brunton%204%20February%202019%20FINAL.pdf (retrieved: 9 May 2019), p. 41.

- ↑ Monger, David / Pickles, Katie / Murray, Sarah (eds.): Endurance and the First World War. Experiences and Legacies in Australia and New Zealand, Newcastle 2014.

- ↑ Abbenhuis, Maartje M. et al (eds): The Myriad Legacies of 1917. A Year of War and Revolution, Cham 2018.

- ↑ Personal correspondence with Ellie Campbell, senior communications advisor at the Museum of New Zealand. Te Papa Tongarewa, 2 April 2019, and Te Papa Museum in Wellington Marks 20th Birthday, issued by nzherald.co.nz, online: https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=11993508 (retrieved: 3 December 2019).

- ↑ Follow-up Survey, p. 5, p. 35.

- ↑ Ross, Kirstie: Conceiving And Calibrating Gallipoli. The Scale of our War, in: Museums Australia 24/1 (2015), p. 27.

- ↑ Follow-up Survey, p. 5.

- ↑ These exhibitions were all sourced from the WW100 site by searching for “Exhibitions” under Activities and Projects, issued by WW100 – New Zealand’s Centenary Programme Ran from 2014 to 2019, online: https://ww100.govt.nz/activities-and-projects (retrieved: 18 February 2019).

- ↑ Follow-up Survey, p. 39.

- ↑ These exhibitions were all sourced from the WW100 site by searching for “Exhibitions” or “Art” under Activities and Projects, issued by WW100 – New Zealand’s Centenary Programme Ran from 2014 to 2019, online: https://ww100.govt.nz/activities-and-projects (retrieved: 18 February 2019).

- ↑ Follow-up Survey, p. 41.

- ↑ Anzac. Tides of Blood, issued by NZ On Screen, online: https://www.nzonscreen.com/title/anzac-tides-of-blood-2015 (retrieved: 18 February 2019).

- ↑ The technical expertise for the restoration was provided by Jackson’s own facility, Park Road Post Production in Wellington.

- ↑ WW100 site search for “Film” under Activities and Projects, issued by WW100 – New Zealand’s Centenary Programme Ran from 2014 to 2019, online: https://ww100.govt.nz/activities-and-projects (retrieved: 18 February 2019).

- ↑ Follow-up Survey, p. 39.

- ↑ WW100 site search for “Plays” under Activities and Projects, issued by WW100 – New Zealand’s Centenary Programme Ran from 2014 to 2019, online: https://ww100.govt.nz/activities-and-projects (retrieved: 18 February 2019).

- ↑ Salute, issued by RNZB, online: https://rnzb.org.nz/shows/salute/ (retrieved: 18 February 2019).

- ↑ WW100 site search for “Concerts, festivals and performances” under Activities and Projects, issued by WW100 – New Zealand’s Centenary Programme Ran from 2014 to 2019, online: https://ww100.govt.nz/activities-and-projects (retrieved: 18 February 2019).

- ↑ The Scars of War, issued by Auckland Philharmonia Orchestra, online: https://www.apo.co.nz/about-apo/news-stories/the-scars-of-war/ (retrieved: 18 February 2019).

- ↑ Follow-up Survey, p. 39.

- ↑ Migone, Paloma: War Memorial Park Blessed, issued by RNZ, online: https://www.radionz.co.nz/news/regional/269566/war-memorial-park-blessed (retrieved: 18 February 2019).

- ↑ Memorial Park, issued by Waka Kotahi. NZ Transport Agency, online: https://www.nzta.govt.nz/projects/wellington-northern-corridor/the-tunnel-to-tunnel-inner-city-transport-improvements/memorial-park (retrieved: 18 February 2019).

- ↑ First World War Centenary Programme Final Report, p. 26.

- ↑ WW100 site search for “Memorials and monuments” under Activities and Projects, issued by WW100 – New Zealand’s Centenary Programme Ran from 2014 to 2019, online: https://ww100.govt.nz/activities-and-projects (retrieved: 18 February 2019); see also About, issued by Archibald Baxter Memorial Trust, online: http://www.archibaldbaxtertrust.com/about/ (retrieved: 18 February 2019).

- ↑ Places of Remembrance Project, issued by WW100 – New Zealand’s Centenary Programme Ran from 2014 to 2019, online: https://ww100.govt.nz/places-of-remembrance-project (retrieved: 18 February 2019).

- ↑ National War Memorial and Carillon, issued by Fletcher Construction, online: http://www.fletcherconstruction.co.nz/projects/community/national-war-memorial-and-carillon (retrieved: 18 February 2019).

- ↑ WW100 site search for “Memorials and monuments”.

- ↑ Choay, Françoise: The Invention of the Historic Monument, Cambridge 2001, p. 12.

- ↑ WW100 site search for “Memorials and monuments”; Nga Puha Mahara. Petals of Remembrance, issued by Boffa Miskell, online: http://www.boffamiskell.co.nz/news-and-insights/article.php?v=nga-pua-mahara-petals-of-remembrance (retrieved: 18 February 2019).

- ↑ Record Turn-outs at Packed Anzac Day Services, issued by 1 News Now, online: https://www.tvnz.co.nz/one-news/new-zealand/record-turn-outs-at-packed-anzac-day-dawn-services-6300165?variant=tb_v_1 (retrieved: 18 February 2019).

- ↑ See “Remembrance. We Remember” on Past Projects, issued by Wellington City Council, online: https://wellington.govt.nz/services/community-and-culture/arts/outdoor-public-art/temporary-public-art/past-projects (retrieved: 18 February 2019).

- ↑ Upcoming Significant Dates, issued by Fields of Remembrance New Zealand, online: https://www.fieldsofremembrance.org.nz/events.html (retrieved 18 February 2019).

- ↑ First World War Centenary Programme Final Report, p. 39.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 3.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 4.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 41.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 52.

- ↑ Hastings, David: The Odyssey of the Unknown Anzac, Auckland 2018.

Selected Bibliography

- Hucker, Graham: A determination to remember. Helen Clark and New Zealand's military heritage, in: The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society 40/2, 2010, pp. 105-118.

- Phillips, Jock: To the memory. New Zealand's war memorials, Nelson 2016: Patton & Burton.

- Ross, Kirstie: Conceiving and calibrating Gallipoli. The scale of our war, in: Museums Australia Magazine 24/1, 2015, pp. 22-30.

- Volkerling, Michael: The Helen Clark years. Cultural policy in New Zealand 1999-2008, in: The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society 40/2, 2010, pp. 95-104.