Introduction↑

Writers have focused on many aspects of medicine and World War I: organization of care, physicians, and patients, including invalids, the disfigured, or the psychologically wounded. This research has resulted in a multitude of different, often national but sometimes comparative studies.[1] These different approaches are proof that one cannot speak of the medical care of World War I. Medical care during wartime varies as much as the war itself. It depends on the time period, weaponry used, geography, climate, military strategy, politics, the economy, the number of soldiers being treated, the amount of medical materials and of course the numbers, skills and knowledge of doctors and nurses. It is this paper’s purpose to bring to light the varying methodologies of medical care during World War I, but also to show that underneath all these differences there were some common characteristics.

The humanitarian and military necessity of medical care↑

World War I was a war of unprecedented slaughter, leaving millions dead. There were tens of millions wounded as well, and as a result of the violence and unhealthy circumstances of wartime, these wounded were surrounded by sick soldiers.[2] This made a vast military medical apparatus not only a humanitarian, but also a military, necessity. In certain ways this medical effort was successful. Up until then, the death of most soldiers was caused by disease rather than wounds. Although disease remained the main cause of manpower depletion, World War I was the first war of some length in which this statistic was turned around, thanks to for instance hygienic measures, vaccination programmes or blood transfusion. However, for this to happen the army medical corps had to grow rapidly after the war began. Furthermore, more and more sick and wounded were quickly declared “healthy”, a word defined as “healthy enough to return to the field of battle”. As a result medical care became an important source of “fresh” warriors, and therefore an indispensable part of the war effort. In other words: without medical care, manpower shortages would have been even more severe and morale even harder to maintain. Without medical care, battles would have been shorter and fought with fewer men.[3]

This by far happened against physicians’ will. Medical opposition to the war was scarce. In 1914, physicians found their way to frontline or military base hospitals en masse. In general, the idea of “war enthusiasm” should be looked at with skepticism, but many doctors were indeed eager to get involved in the war effort. Besides being proud patriots, they not only believed their oath directed them towards places of severe medical need, but Social Darwinist and/or eugenicist physicians in particular saw an abundance of possibilities for experimentation. Wounds never seen before, in numbers never seen before, promised there would be unlimited research possibilities, on an individual and societal scale. War, they said, was not an enemy of medicine; it was its teacher. Some even saw war as a colleague, for, despite the numerous individuals who would be killed or maimed, it would make the people, the nation, and the race physically and psychologically stronger.[4] Furthermore, physicians saw war as an opportunity to demonstrate the worth of their particular specialty, including besides obvious fields such as psychiatry, surgery or orthopedics, also cardiology and gynecology. Gynecologists/obstetricians had to ensure that the next healthy generation of soldiers would be born, for there was no telling how long the war would last or if it would be the last one waged. It is telling that, at least in Germany, the number of doctors in favor of abortion gradually fell as the war lasted.[5]

The organization of medical service↑

In all warring countries - and many non-warring countries - physicians voluntarily joined the Military Health Service (MHS) or one of the auxiliary corps in great numbers, making them one of the largest groups of academically-trained professionals participating in the war effort. During the war the number of doctors and nurses kept increasing, and they took care of millions of sick and wounded in hospital beds, on stretchers, on blankets on the floor, or on the floor itself, either inside or outside field hospitals. No matter how vast healthcare provisions were, and no matter how hard physicians and nurses worked, medical care was no match for the number of wounded: between 15,000 and 20,000 daily, on average, with up to 100,000 on days with particularly heavy fighting. Given the circumstances, not the failures, but the successes were surprising. Particularly on the Western Front, medical officers had to combat wounds and illnesses of an enormous variety and spanning all degrees of severity. Their successes would have been impossible without a high degree of organization.

Despite some national differences, the organization of the medical line was generally the same throughout all armies, with first aid at the front, advanced dressing stations close to the front, followed by field hospitals or casualty clearing stations (CCS) near the front. (In 1916 the British had more than fifty CCSs in France and Belgium only, housing between 500 and 1000 patients each.)[6] From there, some of the wounded were transferred further back to base hospitals. Exceptions were determined by a combination of geography, climate and style of warfare - often determined by the former two. Examples are Gallipoli or the African jungle. The closer to the front, the less “real” medical care was given. The priority was triage and making a patient ready for the journey back. If times were quiet, triage practices followed medical standards, i.e. the severely wounded should be treated first. However, in times of severe battle, when the need for “fresh” troops was at a peak, the interests of the military determined triage methodology. Heavily wounded patients were put aside, given a dosage of morphine (if available), and left to die. The slightly wounded cost less time and were considered of greater importance because they could be made fit for battle again. This, to a great extent, also determined the popular policy of treating the wounded as quickly as possible and as close to the front as possible. This methodology of care profited and resulted from static trench warfare, providing health workers a more or less fixed place to work, fairly close to front lines. Recovery rates rose especially for simple wounds. The further away and the greater the time span between being wounded and being treated, the more difficult it was to get soldiers declared “fit for duty” and send back to the front. Nevertheless, ambulances and hospital trains, carrying the wounded from one spot in the line to another, became a very frequent sight in warring countries. According to German writer Leonhard Frank (1882–1961), the trains were the central metaphor of the war as they literally brought home its horrors.[7]

The field hospitals or casualty clearing stations - named so as not get hopes up too high - were the places where not only for the first time in the medial line women could be detected, but also where operations were performed closest to the front, although often in circumstances anything but tidy and hygienic. Field hospitals and casualty clearing stations were messy, at times filthy, and frequently overloaded. As said, the wounded were often lying on the ground or outside, not far from stacks of amputated arms and legs in a corner. No wonder soldiers nicknamed them the chopping block or the butchers’ kitchen.[8]

The further away from the line, the better circumstances got, but overpopulation remained a problem even in the base hospitals, in spite of accepting only the most severely injured. In Britain alone base hospitals expanded from a 40,000-bed capacity at the end of 1914 to 365,000 at the end of the war. And in 1917 in the Berlin area alone, there were 140 with a capacity twenty-fold greater than in the pre-war years. However, in spite of organization being more or less similar, medical care itself, as said, differed severely from time and place.

Differences in medical care↑

When examining the medical service of World War I, it is first necessary to determine who is to be included. Stretcher-bearers, although the first responders to injuries, are frequently forgotten. There were hardly ever enough of them, and their ranks suffered considerable losses. In theory, four stretcher-bearers were expected to bring a wounded man back to the first aid post within the hour, which could only be achieved if the violence had stopped and ground conditions were reasonable. In reality it often took up to eight men, depending on the mud. The stretcher-bearers frequently felt worn out after delivering a single wounded man to a first aid post. Seeing stretcher-bearers taking a break or asleep, while the wounded remained in the field troubled the other soldiers, such as Louis Barthas (1879-1952),[9] a hostile attitude certainly not lessened by the order to preferably bring back the wounded they felt had the best change of eventually being fit enough for active service.[10] It does not take way the fact that few men could shoulder their human burdens in the heavy rain and gun fire.

However, no matter how important the stretcher-bearer’s task in the medical line, the main focus of this study is still the medical care providers who bandaged, distributed pills, operated on the sick and wounded, and combated the constant threat of infection - by the way, leaving them often as fatigued as the stretcher-bearers were.[11] Their main task was preventing soldiers from getting sick in the first place. Although a task not prioritized by many physicians, nevertheless considerable effort was put into preventive care because sick soldiers posed a threat to healthy ones, and because, as Austrian soldier-novelist Andreas Latzko (1876–1943) wrote, soldiers had to be healthy enough to return to battle and face further injury and death.[12] In short, soldiers were obliged to do everything within their power to stay at their post and not in the hospital, which made sense in theory but not in trench circumstances, where disease spread easily. Nevertheless, in some armies, certain conditions were not treated as much as criminalized. Contracting them was considered an infraction.

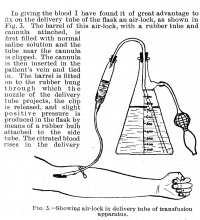

The care doctors and nurses delivered changed over the course of 1914 to 1918 as a result of experience gained, a rise in the number of physicians and nurses, more refined medical supplies, and improved techniques. In August 1914, for instance in the Belgian army and the British Expeditionary Force, improvization ruled the day. Pre-war planning had failed, if “planning” is considered the right word. Material was qualitatively and quantitatively insufficient. Physicians and nurses short in numbers. Knowledge on specific war-injuries was lacking.[13] Later on, specialized centers (e.g. for abdominal surgery) were set up by nearly all warring countries some even rather close to the front. Consequently, by the last year of the war, the survival chances of for instance those suffering abdominal wounds - if they were lucky enough to reach the hospital alive - had risen considerably, especially in the Allied armies. This was mainly due to the introduction of blood transfusion, to a high degree resulting from American war participation. The medical services of the Central armies were far more skeptical about blood transfusion.[14]

Despite this specialization, advancement over the years suffered from the constant pressure of new patients and a constantly rising demand for “fresh” men. This left little time for to develop improvements in procedures or practices. There was hardly any time for further education and, consequently, newly arrived doctors were no more or less skilled than their predecessors. Standards of care actually dropped as the war continued. Furthermore, the ongoing search for soldiers led to a drop in physical and mental requirements for new recruits. Medical tribunals were turned into a variant of industrial conveyor belts, perfectly captured in a drawing by George Grosz (1893-1959) in which doctors diagnose a skeleton fit for service. The result was that doctors and nurses got an even harder time than they already had. The fact that their numbers also constantly rose indicates that, especially in the last year of the war, the doctors, nurses, and orderlies too were not always as qualified as they should have been. So, as the war lasted, more and more hardly qualified caregivers had to cope with more and more soldiers who in fact were physically and mentally unfit to serve.[15]

Even if appropriate treatments and cures for known causes of illness and death were developed over time, new medical puzzles arose, such as gas gangrene, trench foot, and trench fever. These ailments often were caused by the living conditions: cold, gas- and water-filled trenches with vermin and decaying corpses all around. In 1918, Spanish influenza compounded these existing issues, leaving medicine virtually impotent and killing soldiers and civilians by the masses. Then there was the psychological condition now commonly referred to as shell shock, caused by stress that derives from constant violence, a feeling of uselessness, and, above all, fear. The fear was wide-ranging, both physical and psychological: of shells and bullets and their resulting wounds; of becoming merciless killers; of the consequences of not killing when necessary. Several times during the war it was stated that it was “cowardice” that kept the men from disobeying orders and fleeing.[16]

Politics, economy, ideology, culture, religion, ideas about society versus individual, and ideas about the significance of life all determine medical research and practice, and this held true in the diverse medical services of World War I.[17] The ways in which physicians and nurses treated the wounded and sick, as well as the types of wounds and illnesses they came to treat, depended primarily on their skills and the number of care providers available. There was hardly ever a sufficient number of people available to help, and medical materials often were in short supply. Medical care depended on such highly differing matters as how harshly a particular army was struck, the national organization of medical care, cultural or national ideas about medical care, and the nation’s history of health insurance. It also depended on the nature of the wounds themselves. For instance, in general a soldier who suffered facial disfigurement received better treatment than psychologically affected soldiers.[18]

Medical care also differed depending on which members of society the nation prioritized to receive treatment. German doctors, also military ones, voiced their concerns that the civilian health situation was worrying and should be prevented from deteriorating, if only because this would seriously harm home front support. However, because of Germany’s wartime strategies and external factors like the Allied blockade, these worries became not only reality, but impossible to rectify. French doctors, on the other hand, always put soldiers’ health first, as demonstrated when they vacated women and children from tuberculosis hospitals to make way for soldiers and men who might become soldiers.[19]

The trajectory of medical care depended on the ideology, religious beliefs, and/or character of the individual doctor or nurse. There were doctors, especially in the voluntary aid organizations, who had the courage to regularly oppose military demands if they thought these orders contradicted the patients’ interests.[20] It would be mistaken, however, to call this attitude typical; most doctors followed orders.[21] This last point, as most of the studies do, points out the military task of medicine. Military medicine - or better: nearly all medical care provided during the war - was not a labor of love, but rather a part of warfare and the war effort.

Medical care also differed from place to place. It mattered if the doctors and nurses were stationed near the swamps of the Belgian Yser, the mud of Ypres, the clay of the Somme, the shores of Gallipoli, the sand and heat of the Middle East, the jungle of Africa. At Salonika, the base of the British Balkan campaign, hospitals were in a dreadful state, every once in a while complicated even more so by extreme cold. Illnesses such as malaria, sand fever, typhoid, and dysentery raged among patients and doctors alike. In Egypt, British supplies fell short, and soldiers were exposed to the severe threats of dust, scorpions, and flies. Medical personnel often considered working in the Eastern Mediterranean a bigger challenge than working on the Western Front.[22]

It mattered if they had to treat patients near the trenches in the west, or the much less static fronts in the east. Of course it mattered if they were stationed on land or at sea. And also healthcare varied depending on whether armies were homogenous or multiethnic and multilingual.[23] There was an abundance of ill troops in the Balkans, the Yser, or in and around the former German East-Africa, whereas wounded soldiers were the predominant affliction in France and Russia. The Balkans were tortured by typhus and other epidemics, resulting in the Serbian army’s staggering death rate of 40 percent.[24] The war efforts in the east, characterized by more movement than in the west, required more frequent transport of sick and wounded than in the west. If their conditions made transport impossible, patients were left behind with the hope that the enemy would be merciful and take over treatment. These problems also occurred in the west in the opening months of the war, and even more so in 1918. For example, it was only because they kept control of the railway system that the Allied medical line did not collapse during the German offensive of 1918.[25]

Different countries, and even different individuals, had varying definitions of what medical care entailed; this impacted matters such as bacteriology, vaccination, and patient rights. There were French protests against the decrease in patient rights, while in Germany the doctor’s will remained on par with a military order, only to be severely protested against after the war. In general, across national boundaries, patient rights were threatened by the war in the short term. Doctors believed that, especially in times of war, medical authority should override the patient’s will to ensure the overall strength of the army. Even ignoring the fact that soldiers had to obey physicians because they were officers, the pressures of total war, the wish to contribute to the war effort, and the sheer volume of soldiers requiring treatment were bound to cause a shift in doctor-patient relationships. This shift was not to the patient’s advantage. Punitive action, however, was rare. To get their will done, in general the doctors relied more on moral persuasion.[26]

Also with regard to prevention, insights differed. For instance, in the de-lousing process, the British set their faith in personal hygiene, while the Germans trusted disinfection.[27] And this goes for vaccination as well, an activity in which varying attitudes towards patient rights surfaced. Differences in vaccination practices arose, in part, from the fact that Germany conscripted its soldiers, but the British did not until 1916. As a result, vaccination was always obligatory in Germany, but voluntary in Britain. Compulsory vaccination could have deterred British recruits from enlisting, since it would fly in the face of that nation’s voluntary traditions. The British used the Germans’ compulsory vaccination policy in their propaganda, claiming it proved the authoritarian character of the German political system - even though their medical system was decentralized. However, British vaccination was really only voluntary in theory; most soldiers actually thought it was compulsory. It took considerable strength to resist medical and military pressure to get vaccinated, especially since the medical benefits were undeniable: the proportion of British soldiers contracting typhus dropped from three per 1,000 in 1915 to 0.2 per 1,000 in 1918. The rate of infection amongst those refusing vaccination in 1916 was 15 times higher than the average for the army as a whole.[28]

Religious beliefs had a great influence on the ways doctors treated venereal diseases, individually as well as on the state level; some cases led to criminalization. Nevertheless, this affliction constituted between 3 and 8.5 percent of all disabling conditions.[29] Care was also influenced by the treating physicians’ or nurses’ status as army health officers, Red Cross workers or pacifistic Quakers. Did they serve in a conscription army or an army of volunteers, in which facilitating organizations such as the Red Cross were less strictly incorporated? Were they part of a health service of a warring country or part of a neutral state ambulance (e.g. the Netherlands or America pre-1917) who were likely to be a bit more inclined to pity the sick and wounded. Were health workers male or female, such as the “Women of Royaumont”, who managed an entirely female hospital in France, doctors and ambulance drivers included?[30]

Furthermore, care depended on whether the sick and wounded were treated at the front or in base hospitals. Young, inexperienced doctors were more likely to be stationed at or near the front, so the more severe cases went to base hospitals, where patients could be seen by university doctors. By virtue of education and status, these doctors tended to be more nationalistic and were often unaware of what their patients had gone through during the war. They distanced themselves from patients, in contrast to the more informal and closer doctor-patient relationships at or near the front. Military frontline doctors, in general, viewed treatment pragmatically; they were mainly concerned with crisis management, employing whatever methods would do the trick to heal or at least comfort their patients. Base hospital doctors struggled with the same personnel shortages as on the front lines, but they still wanted to prove their insights right and demonstrate the worth of their specific specialty.[31]

The attitudes of non-medical officers towards medical affairs, as well as the attitudes of those on the home front, factored into how patients were treated. Most officers had a keen interest in medical matters because manpower and morale largely depended on the success of treatment. But there were officers - Central and Allied - who totally neglected these matters.[32] In general, the home front paid careful attention to medical matters; civilians wanted to see their husbands, sons, and brothers being taking care of properly. To ensure necessary treatment was given, war loans were handed out, collections made, and money transferred. Still, questions arose about treating men with abdominal wounds because they were unlikely to return to active duty. The support the medical effort received from the home front was reciprocated: proper medical care served as an instrument to keep up morale on the war front and the home front.

However, the home front’s attention was not equally divided amongst the different battle sites. The concern often depended on the distance between country and battleground, which sometimes led to catastrophic results. For instance, the combination of non-medical officers’ lack of interest in medical affairs and the home front’s lack of interest was a huge factor in the British medical line collapse at Gallipoli. At the Somme in 1916 the line did not collapse, at least not on a Gallipoli scale, thanks to at least in part public interest in the Western Front.[33]

And last but not least, the care of course differed as much as the different wounds and illnesses did. Military medical men used to say that they could tell the differences in warfare in the wounds they had to heal.[34] A war that makes frequent use of artillery results in different wounds than one dominated by guns or machetes; an open war in European fields leads to wounds less frequently seen in guerrilla warfare in the jungle. But even within the same war the differences can be significant; World War I was no exception.

Most wartime physicians - and contemporary historians of medicine - have focused on wounds, not illness. Ultimately, though, the latter was the main cause of inactive man-days. The sick not only outnumbered the wounded, but also took longer to recover. Despite the statistics, soldiers tended to be less afraid of illness and more afraid of sustaining wounds, also because of possibly following complications such as gas gangrene, although the Spanish influenza in 1918 probably was an exception.

World War I was characterized by a multitude of gruesome wounds and the complications resulting from them, the sight of which often flabbergasted doctors and nurses, certainly, but not exclusively, those coming from ordinary civilian surroundings. Shells maimed tens of thousands of soldiers for life. One such wounded soldier, who had lost his face, was described by French nurse Henriëtte Rémi (1885-1978): “All that is left are his eyes, covered by a veil; his eyes seem to see.”[35] These kinds of wounds were caused by bullets, especially ricochets, as well as grenades and shells, especially those filled with shrapnel. Splinters and fragments decapitated and eviscerated soldiers in arbitrary patterns. If the wounded survived, they, along with their doctors and nurses, frequently wondered if they would have been better off dead. Invalids came to be a normal sight in all of the warring countries. Germany alone had about 2.7 million permanently incapacitated men, out of 13 million enlisted. Approximately 67,000 lost one or more limbs. The staggering number of disabilities had serious financial consequences after the war, further increasing the need for and value of prosthetic surgery and occupational therapy.[36]

Dual loyalty↑

In spite of all the differences in medical care enumerated above, some similarities are to be recognized throughout all armies and fronts. Most physicians - professional military and enlisted or volunteer civilians - wholeheartedly supported the war effort, using their medical skills and apparatus to work toward national victory. Medicine, or healthcare in general, was a tool to further the nation’s goals. Practitioners of military medicine had to try, as much as possible, to save the state from handing out war pensions, for otherwise they could cause the state to go bankrupt. This was the main force behind creating specialty hospitals all over the warring countries. In other words, these common driving forces were more political and military-minded than of a Hippocratic, patient-directed nature. For example, one British physician admitted after the war that in order to “maintain the discipline and morale of his unit,” “the health of individuals may have to be sacrificed temporarily, even permanently.”[37]

This is exactly why the differences between for instance frontline and base hospital physicians should not be exaggerated. Not just because clearing stations, field hospitals, and base hospitals all struggled with overpopulation and were, as German medical historian Wolfgang U. Eckart said, medical factories dealing with the detritus of warfare in all its mental and physical forms.[38] No matter where they were placed, doctors and nurses knew their main task was to get soldiers back into the field as quickly and as much as possible.

In all countries military medicine had the purpose of maintaining the army’s fighting strength. Also they had to boost morale by ensuring the soldiers as well as the home front that if sick or wounded the soldiers would receive the proper care they deserved. Furthermore, they had to detect shirkers and malingerers, serve as witnesses during court-martials and decide whether or not a soldier had suffered a war-related wound or illness, thereby deciding if eventually he would be entitled to a war pension. In order to receive this pension, a soldier had to be declared “wounded,” i.e. “sick or wounded as a result of warfare” (emphasis added). Under this definition, psychologically injured soldiers struggled more than other wounded soldiers to prove they should receive a pension; they were often not even acknowledged to be “sick,” as they had only “invisible” wounds. Wounds or illnesses that could not be seen (and this extended beyond psychological afflictions, even including tuberculosis) were regularly dismissed as nothing not only by non-medical, but by medical officers as well.[39]

How the sick and wounded were treated mirrored the society’s focus on winning the war. Soldiers knew that healthcare was only an extension of this interest in victory, leading them to view the medical system somewhat ambivalently. While the hospital could be an escape from the trenches and no-man’s-land, it was also more of the same. Ultimately, care providers had dual loyalty: to prevent the wounded from dying (“Hippocrates”) and to make the wounded fit for battle again (“Mars”). There were people like the physician-philosopher Theodor Lessing (1872–1936), who worked in a war hospital because it was the one place he could find the classless society he had longed for, but which could impossibly become reality after August 1914.[40] But men like Emil Kraepelin (1856–1926), Clovis Vincent (1879–1947), or Lewis Yealland (1884–1954), made famous by Pat Barker’s 1991 novel Regeneration, are more characteristic. Military doctors had to consider not only the interests of the individual soldier–patient, but also - and primarily - the interests of the state and the military. This concern for the military’s overall wellbeing only strengthened as the war went on, as doctors tended to become more politically conservative and nationalistic. Rehabilitation, an American orthopedist stated, was important because the disabled, mostly working-class soldiers, were potential “centers of unrest”, who without treatment could even evolve into “centers of revolution.” A doctor treating Ernst Toller (1883-1939), a German officer and war-critic, told him that “all pacifists should be executed.”[41]

Individual doctors balanced this dual loyalty against their own beliefs, as well as the illness or wound they had to treat. The wounded, for instance, could count on more understanding and pity from their doctors than could the diseased. This biased treatment continued after the war, for it was harder for soldiers with chronic illness to be recognized as war invalids and receive a pension.

Disfigured soldiers would no longer play a part in the war and would probably never play an economically important role in society. This meant the urge to help them and make their life as pleasant as possible, was almost entirely a medical one. On balance, in their case therefore the emphasis seems to have been more on the interests of the patient than on the interests of the state.

The fate of the disabled differed slightly: They too would never return to the front, but they could still be useful to the war effort or the general economy. With therapy and prostheses they could be put to work in wartime factories and earn a living after the war so they wouldn’t require pensions. Referring to the care for Belgian soldiers disabled during the war, in 1917 a Dutch newspaper wrote that there had been a shift from pity and national gratitude towards a “sober social and economic argumentation,” which, incidentally, could be of great benefit to the invalids, at least according to the paper’s editor.[42] Historian Heather Perry claims that “in their wartime work,” orthopedic physicians and surgeons were doing what was necessary for “the very salvation” of the nation.[43] Pity for the individual was still there, but the focus on the nation’s collective wellbeing grew stronger.

However, the psychologically diseased or wounded were another story entirely. Soldiers who for instance were unable to speak, walk, or see although organically speaking there seemed to be nothing wrong, were often looked upon with disdain or seen as cowards rather than as patients. Doctors and nurses pushed to get them to the front or weapons factory. In the case of France and Britain it usually was the front, for they were seen as “feminized men” who in battle had to prove they had regained their masculinity. In Germany getting them to work at a weapons factory was seen as a satisfactory result, for the mentally damaged soldier was compared to a worker on strike. Nevertheless, in the case of the mentally ill in general the medic’s loyalty on both sides was clear: it was first and foremost on the side of Mars.[44]

As the before mentioned example of Lessing proves, individual doctors responded to this choice between individual well-being and collective responsibility in different ways. Although theoretically physicians often agreed that loyalty should remain with the patient, they also agreed that wartime circumstances did not allow for this to be the case. Consequently, on the whole, most agreed that medicine had to play a role in maintaining manpower. Certainly when fit soldiers were in short supply - which happened more frequently as time went by - doctors had to side with the army’s interests when questionable cases arose. Whether or not “war is good for medicine,” there is little doubt that in the years 1914-1918 medicine was good for war.[45] Medicine was not “a tiny island of peace within a sea of violence”, as was in different wordings regularly stated since the middle of the nineteenth century especially with regard to Red Cross aid.[46] Medicine did not stand outside the war; it was an essential part of it and the conditions of World War I made this even more sure than usual.

These war-conditions led to a wealth of encounters with bacteria and unhygienic conditions rare in peacetime. This discredited the by many physicians and historians supposed “goodness” of war for medicine.[47] The experience gained in wartime, so they said, resulted in the saving of many lives in subsequent times of peace. And indeed, the years 1914-1918 saw medical advancements, plastic surgery and orthopedics being the probably best examples. However, these innovations did not mean that World War I, overall, was good for medicine, if only because every four-year period since the middle of the 19th century, be it wartime or peacetime, has shown medical advancement. In fact, the period most hailed for its medical innovations was the decades of peace after the Franco-Prussian War. However, there are questions to be asked regarding the war-years themselves. The conditions seen, the wounds sustained, the illnesses caught, the problems derived from them and the treatments developed; they were often specific for that particular time and place. For instance gas gangrene was a menace, but practically disappeared after the war, as it had been rare before August 1914. Also, if the war enhanced medicine, it in general only did so in fields considered to be of interest for soldier’s health. Other fields of medicine, considered to be of interest particularly to civilians, suffered. According to some this should even be taken more broadly. German historian Susanne Hahn states that the war “greatly impeded medical developments, since it prevented the medical profession from fulfilling their potential”.[48] Furthermore, although circulation of knowledge did not come to a complete halt, it certainly decreased. Medical findings of “enemy” physicians were not trusted, for even the medical world could not escape enemy imagery.[49]

The questions, then, include: Was the advancement completely owed to the war? Were wartime inventions of any use outside war circumstances? Were the inventions shared according to international medical ethics, saving the lives of compatriot and enemy soldiers alike? Were medical ethics breached in the process of making medical breakthroughs? Did the war also contribute to a medical standstill? These kinds of questions have led some physicians, nurses and (medical) pacifists to flip the claim, even to the point that they not only consider “medicine good for war,” but by going so far as to say that “medicine should stay away from war.”[50]

Dual loyalty explains why patients were not always satisfied with their medical care, and sometimes outright distrusted it. Not for nothing the British Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) was sometimes nicknamed “Rob All My Comrades.”[51] Medical care during the war magnified the discrepancy between physicians’ intentions and patients’ perception. Even if the physician’s intentions were good from a patient’s perspective, even if the patient’s wellbeing had been at the heart of the aid given, the patient’s distrust remained, complicating treatment and influencing its outcome. This in turn further contributed to a growth of distrust, a distrust probably best shown in the writings of an infuriated Oskar Maria Graf (1894–1967). He accused his physician of being an enemy of the sick and wounded soldier, even more so than non-medical officers, who knew no better. Under the guise of humanitarianism, the physician used his skills to get the sick and wounded back to the war - to kill or be killed.[52] As often, this situation in itself is not unique to war-circumstances, but they did manifold and strengthen it. Doctors were referred to with names such as “the torturer.”[53] The nurses did not entirely escape this verdict. They were not only depicted as angels looking out for the wounded, but also as the opposite: whores who only had an eye for the top brass.[54] This is certainly not the only side to the story, however. Medical care was also defined by physicians and nurses who were trying to cope, to the best of their ability, with the enormous number of sick and wounded, delivered every day of battle from August 1914 until November 1918. It simply often proved to be a mission impossible.

The psychologically wounded↑

Several specialisms profited from the war, using it to prove their worth, such as cardiology, orthopedics and, as said, even gynecology. This certainly goes for psychiatry and neurology. Psychiatrists and neurologists (in those days often not separated) had a fairly easy task showing their specialism’s importance for the war-effort, and not only because they claimed they could heal the psychologically damaged soldiers. For instance, German neurologist Kurt Singer (1886–1962) wrote that a strong nervous system - and therefore neurology - was the key to military success. Strong nerves were indispensable to military discipline, since they enabled a man to obey.[55]

Base hospitals tended to specialize, and soon a fair portion of them was reserved for the many officers and men overtaken by the psychological strain of war. To discuss it in this way, though, is anachronistic; during World War I the majority of doctors saw the strain of war at best as one of many factors influencing the problem. This attitude clearly reflected nationalistic sentiments, leading to ambivalence among some specialists, including neurologists and psychiatrists but certainly not limited to them, eager to show their contribution to restoring damaged men to active duty. Nationalism dictated that “war” was not to blame. So war not only gave the possibility to show the specialism’s worth, it also strongly influenced the way this was done.

If not simply labelled cowards, soldiers were (often wrongly) diagnosed with hysteria, or neurasthenia. Hysteria was a diagnosis made on the basis of symptoms, not their presumed cause. The symptoms consisted of partial or total loss of control over bodily functions and might be expressed in convulsions or paralysis. Neurasthenia used to be diagnosed when the most prominent symptom was nervous exhaustion, but during the war soon became an umbrella term covering all sorts of mental ailments originating in fear. The key difference between them was that the latter could have external causes, whereas hysteria was explained entirely out of the patient’s own character weakness and/or an inherited family disease. A diagnosis of neurasthenia was therefore less stigmatizing. Even when symptoms were similar, hysteria was more likely to be the diagnosis for a soldier of lower rank, whereas an officer, generally coming from the same social class as the physicians, would likely be declared neurasthenic. However, recent research has shown that class differences in diagnoses were, at least in Germany, probably not as great as is often thought.[56] However, these are but some of the diagnoses possible, even if we leave national differences in diagnosis and terminology aside.

British soldiers could also be diagnosed as shell shock wounded (qualifying them for pension rights), or shell shock sick (denying pension rights). As said, the psychologically wounded or sick were often treated more harshly and often declared “sick” for many reasons: unfamiliarity with the conditions at hand; the invisibility of and subsequent denial of the phenomenon; the possibility of feigning psychological illness; and the desire to prevent an outbreak of a feared psychiatric epidemic. One of the ways health workers attempted to nip this in the bud, was to avoid war-related terminology, for they feared that if the ailment’s name had a linkage with war, soldiers would be more eager to think they did their bit and more easily inclined to demand a pension. For instance, British doctors soon avoided the term “shell shock,” replacing it with “Not Yet Diagnosed (Nervous).” In September 1918, British doctors were forbidden from declaring patients “shell shock wounded.”[57]

In Germany in 1916 the theory of traumatic neurosis, now at the heart of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), was declared wrong and out of date. The shared assumption became that war in itself could not be a reason for psychological suffering. According to this view, everyone with mental disorders was sick (i.e. suffering from something not attributable to war), not wounded; if there was somehow a connection between war and mental illness, it was only that the war set the already-present weakness in motion.[58]

As a consequence, soldiers suffering from shell shock, Kriegsneurose, or trouble nerveux had a hard time, certainly when they were transferred to base psychiatric-neurological hospitals. These should, so was said and put to practice, not be a place of rest, but one resembling a military barracks as much as possible. It showed that treatment should not be considered being away from the war. And it showed that psychiatrists — who had a harder job being taken seriously by their non-medical (and often also medical) colleagues than their colleagues treating visible wounds — tried to show they were as tough as the rest of them. This also was reflected in the treatment given. There were many different treatments for serious cases amongst soldiers, but they all came down to a forceful, authoritarian, and swift therapy, called “quick cure” by the British, or Überrumpelungsmethode by the Germans. Those using this treatment guaranteed it would be successful, but clearly success only meant disappearance of symptoms.[59]

However, there were differences in how the psychologically affected soldiers and officers were treated in each national army. The Austrians, for example, used electric treatment for a longer period during the war and more harshly than elsewhere. Their multiethnic and multilingual army was desperately in need of a treatment that required little talking. Significantly, psychoanalyst Fritz Wittels (1880–1950) wrote in his 1923 novel, Zacharias Pamperl that the neurologists had reintroduced torture, clearly making the case for the value of the other medical field meant to deal with psychiatric problems: psychoanalysis.[60]

In this period, psychoanalysts deemed it important to participate in “keeping the interest of one’s own specialty under close watch.” They saw a change for promoting their more humane treatment style in attacking the biolological psychiatrists and neurologists. This was seen in the trial against Austrian psychiatrist Julius Wagner-Jauregg (1857–1940). A former patient claimed that under Jauregg’s authority, electricity had been used to terrify him back to health. Jauregg himself had not used electricity. He had injected his patients with malaria bacteria after having observed other patients improve as a result of fever. But, as with electricity treatments, some of his patients died from the injections. During Jauregg’s trial, Sigmund Freud (1856–1939), the father of psychoanalysis, argued that wartime psychiatrists had served as “machine guns behind the front.” Like the guns who forced the soldiers to go forward, the psychiatrists forced the soldiers to return to the field of battle. In contrast, according to Freud, psychoanalysts had kept their humanity, ignoring the fact that many psychoanalysts had worked towards the same goals as psychiatrists: making patients fit for the front, or at least the arms factory, using hypnosis which could be quite forceful as well. This does, however, show that one should not exaggerate the differences between Freud and Wagner-Jauregg. Psychoanalysis was anything but an accepted form of psychiatry in those days, so Freud argued on behalf of his field. Ultimately, he knew he should not alienate the leading biological psychiatrists, for this would harm the possibilities of development for psychoanalysis. After the trial, he therefore stated that Jauregg surely had had the best interests of his patients in mind and their quarrel was not personal, but strictly professional.[61]

Conclusion↑

Military medicine during World War I was defined by its complexity and multi-faceted nature. Patterns of diagnosis and treatment varied according to the following factors: geography and climate, public and parliamentary interests, severity of disease or injury, the numbers of soldiers and officers needing treatment, the varying knowledge and skills of care providers, the vagaries of transport, and the availability of medicines and medical equipment.

Underlying these different elements, however, there were some general trends that held true on both sides of the line. The war gave specialists the opportunity to raise their specialty’s status by showing its contribution to the war effort. The war also provided an occasion for trying out new treatments and drugs. The war became a laboratory for socially useful but sometimes ethically questionable medical experiments. The nature of the conflict also helped strengthen social Darwinian tendencies among doctors who believed they had to consider the health of army, nation, and/or race, over the needs of the individual. Many doctors worked towards maintaining manpower and morale, and their interest in saving the state from the crushing burden of war pensions led to particular diagnoses.

The conflict between medical and military necessity was played out in myriad ways between 1914 and 1918, and on balance, military necessity emerged the stronger of the two. Partly due to medical care, battles could be fought with more men and could be endured longer, and therefore medical care ultimately not only strengthened the war effort, but also not only saved lives, but has cost lives as well.

Leo Van Bergen, Royal Netherlands Institute of South East Asian and Caribbean Studies, Leiden

Section Editors: Michael Neiberg; Sophie De Schaepdrijver

Notes

- ↑ For the different angles from which the subject can be researched, see for instance: Crofton, Eileen: The Women of Royaumont. A Scottish women’s hospital on the Western Front, East Linton 1997; Thomas, Gregory M.: Treating the Trauma of the Great war. Soldiers, civilians and psychiatry in France 1914-1918, Baton Rouge 2009; Cohen, Deborah: The War Come Home. Disabled veterans in Britain and Germany, 1914-1919, Berkeley et al. 2001.

- ↑ Winter, Jay: Demography, in: Horne, John (ed.): A Companion to World War I, Chichester 2010, pp. 249-250. Official statistics speak of 21,219,152 wounded. The problem with this number is that it is not clear what "wounded" meant. Was this word defined in the same manner everywhere? Was someone who got wounded several times, also listed several times? Was someone with multiple wounds, listed multiple times? But the main problem is that in general military medical statistics are among the most unreliable, if only because doctors were, although informally, instructed to play down own losses (and play up enemy losses). Historically spoken the number of wounded is about four times the number of dead. If Wold War I is in line with this, the number would reach 40,000,000. The numbers of diseased are unknown, but certainly by far outnumbered those of the wounded, in spite of doctors in 1914-1918 using a very strict definition of illness.

- ↑ Van Bergen, Leo: Before my Helpless Sight. Suffering, dying and military medicine on the Western Front 1914-1918, Farnham 2009, pp. 351-365.

- ↑ Sauerbruch, Ferdinand: Das war mein Leben, Munich 1951, esp. the chapter "War: the bloody teacher"; Lessing, Theodor: Das Lazarett, in Lessing, Theodor: Ich warf eine Flaschenpost im Eismeer der Geschichte, Frankfurt am Main 1986, pp. 354-386; Bleker, Johanna/Schmiedebach, Heinz-Peter (eds.): Medizin und Krieg. Vom Dilemma der Heilberufe 1865 bis 1985, Frankfurt am Main 1987, pp. 100-102, p. 123; Glover, Jonathan: Humanity. A moral history of the twentieth century, New Haven/London 2001, p. 196; Eckart, Wolfgang U./Gradmann, Christoph: Medizin, in Hirschfeld, Gerhard/Krumeich, Gerd/Renz, Irina (eds.): Enzyklopädie Erster Weltkrieg, Paderborn et al. 2003, pp. 210-219, esp. p. 217; Lerner, Paul: Psychiatry and Casualties of War in Germany 1914-18, in Journal of Contemporary History 35/1 (2000) pp. 13-28, esp. p. 27.

- ↑ Michl, Susanne: Im Dienste des “Volkskörpers”. Deutsche und französische Ärzte im Ersten Weltkrieg. Kritische Studien zur Geschichtswissenschaft (Vol. 177), Göttingen 2007, pp. 163-180.

- ↑ Harrison, Mark: The Medical War. British military medicine in the First World War, Oxford 2010, p. 33

- ↑ Frank, Leonhard: Der Mensch ist Gut, Zurich 1918, p. 166.

- ↑ Remarque, Erich Maria: Im Westen nichts neues, Frankfurt am Main 1983 [1929], p. 170; Frank, Der Mensch ist gut 1918, pp. 146, 160; Rompkey, Bill/Bert Riggs (eds.): Your Daughter Fanny. The war letters of Frances Cluett, VAD, St. John’s 2006, pp. 82, 83, 111, 146, 150; Thomas, Adrienne: Die Katrin wird Soldat. Ein Roman aus Elsass-Lotharingen, Amsterdam 1938, p. 290.

- ↑ Barthas, Louis: Les Carnets de Guerre de Louis Barthas, Tonnelier 1914-1918, Paris 1983, pp. 148, 194, 533.

- ↑ Hirschfeld, Hans Magnus: Sittengeschichte des 1. Weltkrieges, Hanau without date [1978. reprint of the second, rewritten edition 1965], p. 466.

- ↑ See for instance: Launoy, Jane de: Oorlogsverspleegster in Bevolen Dienst 1914-1918 [War Nurse in obligatory service], Gent 2000.

- ↑ Latzko, Andreas: Menschen im Krieg, Zurich 1918, p. 138.

- ↑ De Munck, Luc/Vandeweyer, Luc: Het Hospitaal van de Koningin. Rode Kruis, L’Ocean en de Panne 1914-1918 [The Queen’s Hospital. Red Cross, L’Ocean and De Panne], De Panne 2012, pp. 25-32; Harrison, The Medical War 2010, pp. 18-22.

- ↑ Schlich, Thomas: “Welch eine Macht über Tod und Leben”. Die Etablierung der Bluttransfusion im Ersten Weltkrieg, in: Eckart, Wolfgang U./Gradmann, Christoph (eds.): Die Medizin und der Erste Weltkrieg, Pfaffenweiler 1996, pp. 109-130. Many hospitals were set up to treat the neurotics, the disabled or the facially disfigured. A famous one for plastic surgery was for instance Queen Mary’s Hospital at Sidcup. The Craiglockhart hospital for the mentally ill has become famous through Pat Barker’s novels.

- ↑ Scott, Peter: Law and Orders. Discipline and morale in the British armies in France 1917, in: Liddle, Peter H. (ed.): Passchendaele in Perspective. The Third Battle of Ypres, London 1997, pp. 349-368, esp. p. 352; Shepard, Ben: War of Nerves. Soldiers and psychiatrists 1914-1994, London 2000, pp. 26, 139, 172; Macdonald, Lyn: 1914-1918: Voices and images of the Great War, London 1988, p. 183; Murard, Lion/Zylberman, Patrick: The Nation Sacrificed for the Army? in: Eckart/Gradmann (eds.), Die Medizin 1996, pp. 343-364, esp. 349.

- ↑ Hynes, Samuel: The Soldiers’ Tale. Bearing Witness to Modern War, London 1997, pp. 60, 62; Johannsen, Ernst: Vier von der Infanterie. Ihre letzten Tage an der Westfront 1918, Hamburg 1929, p. 15; Frey, A.M.: Die Pflasterkästen, Berlin 1929, p. 226.

- ↑ See for instance the difference in aid of the British medical services at Somme and Gallipolli. For this: Harrison, The Medical War 2010, passim.

- ↑ Van Bergen, Leo: For Soldier and State: dual loyalty and World War One, in: Medicine, Conflict and Survival 28/4 (2012) pp. 291-308.

- ↑ Murard/Zylberman, The Nation, in: Eckart/Gradmann (eds.), Die Medizin 1996, passim.

- ↑ De Munck/Vandeweyer, Het Hospitaal van de Koningin [The Queen’s Hospital] 2012, pp. 72-75.

- ↑ Van Bergen, Before my Helpless Sight 2009, pp. 357-359.

- ↑ Harrison, The Medical War 2010, pp. 228-261.

- ↑ I will come to this later on in the section on the psychologically wounded.

- ↑ Winter, Demography, in: Horne (ed.), Companion to World War I 2010, p. 251.

- ↑ Harrison, The Medical War 2010, p. 86.

- ↑ Michl, Im Dienste des Volkskörpers 2007, pp. 76-81; Roudebush, Marc: A Patient Fights Back. Neurology in the court of public opinion, in Journal of Contemporary History. 35, 1 (Jan. 2000) pp. 29-38.

- ↑ Harrison, The Medical War 2010, p. 135.

- ↑ Harrison, The Medical War 2010, pp. 147-152.

- ↑ Harrison, The Medical War 2010, pp. 152-169; Michl, Im Dienste des Volkskörpers 2007, pp. 113-180; Van Bergen, Before my Helpless Sight 2009, pp. 149-160.

- ↑ Besides being researched in the mentioned work of Crofton, they are also the topic in a novel written by MacColl, Mary-Rose: In Falling Snow, Sidney 2012.

- ↑ I will go into this further on.

- ↑ For instance Harrison, The Medical War 2010, p. 253.

- ↑ Chapter on Gallipoli in Harrison, The Medical War 2010.

- ↑ Winters, Victor M.E.: Staal tegen Staal. De oorlogschirurgie van de oudste tijden tot heden [Steal against steal. War surgery from the oldest times to present], Utrecht 1939.

- ↑ Winter, Jay/Baggett, Blaine: 1914-18. The Great War and the Shaping of the 20th Century, London 1996, p. 364. For more information on Henriette Rémi, see: Delaporte, Sophie: "Les défigurés de la Grande Guerre", in: Guerres Mondiales et Conflits Contemporains 175 (1994), pp. 103-121; Delaporte, Sophie: Le corps et la parole des mutilés de la Grande Guerre, in: Guerres Mondiales et Conflits Contemporains, 205 (2002), pp. 5-14.

- ↑ See for instance: Cohen, The War come Home 2001; Whalen, Robert Weldon: Bitter Wounds. German victims of the Great War, 1914-1939, New York 1984.

- ↑ Simpson, K.: Dr James Dunn and Shell-shock, in: Cecil, H./Liddle, P.H. (eds.): Facing Armageddon. The First World War Experienced, London 1996, pp. 502–522, esp. p. 505.

- ↑ Eckart, Wolfgang U.: Röchelndes Knurren von Kampf und Schmerz, in Historische Zeitschrift 54 (2011), pp. 241–264, 259–260.

- ↑ Ellis, John: Eye-Deep in Hell. Trench warfare in World War I, Baltimore 1976, p. 116; Macdonald, Lyn: Roses of No Man’s Land, London 1980, p. 187; Whalen, Bitter Wounds 1984, p. 65; Bourke, Joanna: Dismembering the Male. Men’s bodies, Britain and the Great War, London 1996, pp. 59, 62.

- ↑ Lessing, Das Lazarett, in Lessing, Ich warf eine Flaschenpost im Eismeer der Geschichte 1986, passim.

- ↑ Linker, Beth: War’s Waste. Rehabilitation in World War I America, Chicago 2011, p. 57; Toller, Ernst: Jugend in Deutschland, Reinbek 1984, pp. 72–73.

- ↑ Anonymous, De toekomst der oorlogsverminkten [The future of the war disfigured], in Nieuwe Rotterdamsche Courant, Sunday 17-6-1917, morning edition.

- ↑ Perry, Heather R.: The Thanks of the Fatherland? WWI and the Orthopaedic Revolution in Disability Care, in: Hofer, Hans-Georg/Prüll, Cay-Rüdiger/Eckart, Wolfgang U. (eds.): War, trauma and medicine in Germany and Central Europe (1914–1939), Freiburg 2011, pp. 112–138, esp. p. 136.

- ↑ For the dual loyalty problem in World War I and how this affected different types of wounded and/or sick, see Van Bergen, For Soldier and State 2012, passim.

- ↑ Cooter, Roger: War and Modern Medicine, in: Bynum, W./Porter, R. (eds.): Companion Encyclopedia of the History of Medicine, London 1993, pp. 1536-1572; Van Bergen, Leo: The Value of War for Medicine. Questions and considerations concerning an often endorsed proposition, in Medicine, Conflict and Survival 23/3 (2007), pp. 189-197.

- ↑ For instance: Verwey, L.H.: De vrouwen en het Roode Kruis [Women and the Red Cross], The Hague 1868; Ten Kate, J.J.L.: Het Roode Zwaard, het Roode Kruis. Zang des tijds [The Red Sword, the red Cross. An anthem of time], Amsterdam 1870; Perk, M.A.: Een bezoek aan Metz [A Visit to Metz], The Hague 1871.

- ↑ Lanz, Otto: De oorlogswinst der heelkunde. Rede uitgesproken op de Dies Natalis der Universiteit van Amsterdam [The profit of war for surgery. Speech delivered at the dies natalis of the University of Amsterdam], Amsterdam 1925; Ponteva, Matti: The Impact of Warfare on Medicine, in: Taipale, Ilkka et al. (eds.): War or Health? A Reader, London 2002, pp. 36-41.

- ↑ Hahn, Susanne: How varied the image of the heart trauma has become. The development of cardiovascular surgery during the First World War, in War and Medicine, London 2008, pp. 46-55, esp. p. 47.

- ↑ Van Bergen, The value of war for medicine 2007, passim.

- ↑ Van Bergen, Leo: “Would it not be better to just stop?” Dutch medical aid in World War I and the medical anti-war movement in the Interwar years, in First World War Studies, 2 (2011), pp. 165-194.

- ↑ Graves, Robert: Goodbye to all that, London 1960 [1929], p. 185; Bourke, Dismembering the Male 1996, p. 150.

- ↑ Graf, Oskar Maria: Wir sind Gefangene, Munich 1978, p. 197.

- ↑ Barthas, Les Carnets de Guerre 1983, pp. 104-105, 118, 131, 224.

- ↑ Hirschfeld, Sittengeschichte 1978, pp. 130-132; Hirschfeld, Hans Magnus/Gaspar, Andreas: Sittengeschichte des Weltkrieges. Ergänzungsheft, Vienna 1931, p. 17; Riemann, Henriette: Schwester der Vierten Armee. Ein Kriegstagebuch, Berlin 1930, pp. 172, 190; De Launoy, Oorlogsverpleegster, pp. 67, 97-98, 192, 198, 267-270; Thomas, Die Katrin wird Soldat 1938, p. 295.

- ↑ Lerner, Paul: Hysterical Men. War, Psychiatry, and the Politics of Trauma in Germany, 1890-1930, London 2003, p. 41.

- ↑ Peckl, Petra: What the Patient Records Reveal. Reassessing the Treatment of “War Neurotics” in Germany (1914–1918), in: Hofer/Prüll/Eckart, War, trauma and medicine 2011, pp. 139-159.

- ↑ Myers, Charles M.: Shell Shock in France 1914-18. Based on a war diary, Cambridge 1940, pp. 97-99, 101 (note); Liddle, Passchendaele in Perspective, p. 192; Babington, Anthony: Shell-Shock. A history of the changing attitudes to war neurosis, London 1997, pp. 87-88, 96-97, 120.

- ↑ Lerner, Hysterical men 2003, pp. 67-85.

- ↑ Binneveld, Hans: Om de Geest van Jan Soldaat. Beknopte geschiedenis van de militaire psychiatrie, Rotterdam 1995, pp. 141-145.

- ↑ Hirschfeld, Sittengeschichte des 1. Weltkrieges, p. 360.

- ↑ Kaufmann, Doris: Science as Cultural Practice: psychiatry in the First World War and Weimar Germany, in Journal of Contemporary History, 34/1 (1999), pp. 125-144; Van Bergen, Before my Helpless Sight 2009, pp. 371-374.

Selected Bibliography

- Babington, Anthony: Shell-shock. A history of the changing attitudes to war neurosis, London 1997: Leo Cooper.

- Barham, Peter: Forgotten lunatics of the Great War, New Haven 2004: Yale University Press.

- Barry, John M.: The great influenza. The epic story of the deadliest plague in history, New York 2004: Penguin.

- Cohen, Deborah: The war come home. Disabled veterans in Britain and Germany, 1914-1939, Berkeley 2008: University of California Press.

- Cooter, Roger / Harrison, Mark / Sturdy, Steve (eds.): Medicine and modern warfare, Amsterdam; Atlanta 1999: Rodopi.

- Cooter, Roger / Harrison, Mark / Sturdy, Steve (eds.): War, medicine and modernity, Stroud 1998: Sutton.

- Delaporte, Sophie: Les médecins dans la Grande Guerre, 1914-1918, Paris 2003: Bayard.

- Eckart, Wolfgang Uwe / Gradmann, Christoph (eds.): Die Medizin und der Erste Weltkrieg, Pfaffenweiler 1996: Centaurus-Verlagsgesellschaft.

- Hallett, Christine E.: Containing trauma. Nursing work in the First World War, Manchester 2009: Manchester University Press.

- Harrison, Mark: The medical war. British military medicine in the First World War, Oxford; New York 2010: Oxford University Press.

- Hofer, Hans-Georg / Prüll, Cay-Rüdiger / Eckart, Wolfgang Uwe (eds.): War, trauma and medicine in Germany and Central Europe, 1914-1939, Freiburg 2011: Centaurus Verlg.

- Lerner, Paul Frederick: Hysterical men. War, psychiatry, and the politics of trauma in Germany, 1890-1930, Ithaca 2003: Cornell University Press.

- Linker, Beth: War's waste. Rehabilitation in World War I America, Chicago; London 2011: University of Chicago Press.

- Micale, Mark S. / Lerner, Paul Frederick (eds.): Traumatic pasts. History, psychiatry, and trauma in the modern age, 1870-1930, Cambridge; New York 2001: Cambridge University Press.

- Michl, Susanne: Im Dienste des 'Volkskörpers'. Deutsche und französische Ärzte im Ersten Weltkrieg, Göttingen 2007: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- Reid, Fiona: Broken men. Shell shock, treatment and recovery in Britain, 1914-1930, London; New York 2011: Continuum.

- Reznick, Jeffrey S.: Healing the nation. Soldiers and the culture of caregiving in Britain during the Great War, Manchester; New York 2004: Manchester University Press.

- Thomas, Gregory Mathew: Treating the trauma of the Great War. Soldiers, civilians, and psychiatry in France, 1914-1940, Baton Rouge 2009: Louisiana State University Press.

- Van Bergen, Leo: Before my helpless sight. Suffering, dying and military medicine on the Western Front, 1914-1918, Farnham; Burlington 2009: Ashgate.