Introduction↑

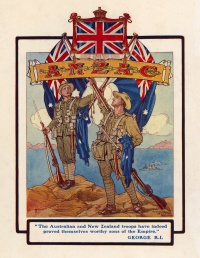

Anzac Day is the premier ritual day of war remembrance in the New Zealand calendar. Held each year on 25 April in both New Zealand and Australia, Anzac Day commemorates the opening date of the First World War Gallipoli campaign. This campaign carries great significance for New Zealanders, and its events have been powerfully mythologised in the years since its occurrence. Anzac Day, however, has expanded past simply remembering Gallipoli or honouring the dead of the First World War; it is now an occasion to mark all New Zealanders who have been killed or wounded during times of war, and of those who have returned from active service.

Anzac Day is named after the military abbreviation for the combined unit in which New Zealanders served during the Gallipoli landings, the Australia and New Zealand Army Corps. Over time the word Anzac has also come to be used as a broad label for the soldiers from New Zealand and Australia who served during the First World War (although this usage is more common in Australia). It also describes the mythology that proponents in New Zealand and Australia placed onto these troops both during the Great War and since.

Anzac Day has not only been a day of remembrance, but at certain points in its history it has been a day of conflict. Some of these conflicts have been practical; declining attendance figures in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War for instance, prompted fundamental changes to activities and entertainment allowed after memorial services. Some of these conflicts have been more fundamental. During the Vietnam era, conflict occurred when protesters used the space to denounce the legitimacy of this war, and to promote contemporary social issues.

The rich history of Anzac Day in New Zealand reflects these challenges and concerns. This entry will look at the origins of Anzac Day in the period between 1916 and 1921, the development period from 1921 to 1945, the challenges for Anzac Day after the Second World War, and finally how Anzac is practised today.

Anzac Day, 1916 to 1945↑

The First World War↑

The first New Zealand Anzac Day was held on 25 April 1916. This was the first anniversary of the 1915 Gallipoli landings, and was held even though the campaign in question had already been abandoned due to it being a costly failure. After nine months on the shores of the Dardanelles, January of 1916 saw the complete evacuation of the Entente Powers from that area.

Although the Gallipoli campaign is sometimes described as a national New Zealand military "baptism of fire", New Zealanders had previously been involved in other military experiences. These most notably included the violence of the New Zealand Wars (1845-1872), and the Second Boer War of South Africa (1899-1902). Compared to these conflicts, however, the Gallipoli campaign was exceptionally bloody. For nine months, New Zealanders were engaged on the Gallipoli peninsular, with a total of 2,721 New Zealanders killed and a further 4,752 wounded. The speed with which Anzac Day was organised after the campaign reflected the widespread public desire in New Zealand to remember and mourn these men; this, in turn, made it attractive to the New Zealand government, which felt that a commemorative day would be an appropriate way to mobilise support for the war effort. Services were also held throughout Australia, and also in London where the King attended a remembrance service at Westminster Abbey.[1]

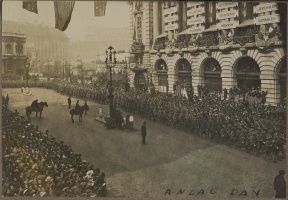

Anzac Day was, and continues to be organised at the level of the local city and district councils. In early 1916, rural and city Mayors worked with government approval to construct Anzac programmes deemed appropriate for the day.[2] The form developed remarkably consistently across the country, with religious elements featured prominently. Inter-denominational services were held in public outdoor spaces and in churches. Catholics, barred from interdenominational services by their beliefs, held separate church services in their own venues. In the larger centres, civic services and dinners for returned servicemen were also held. Commonly, these services were addressed by the local mayor, a suitable returned military officer, or an Anglican minister or Catholic priest. Parades were also common, consisting of martial or semi-martial figures; wounded personnel, returned soldiers, territorial force volunteers, and sometimes firemen and military cadets.[3] The sermons and addresses at these early wartime Anzac Day commemorations emphasised pride; pride in the heroism of the soldiers, the achievements of New Zealand's military contribution, and pride over New Zealand’s loyalty and service to Empire. Participants at these events also expressed sorrow for both those wounded and killed. Monetary contributions for charitable wartime funds were collected, but unlike similar occasions in Australia, these events lacked overt recruiting appeals for the most part.

Elements derived from these early days do linger into the present, but these early Anzac Days evolved rapidly in the context of the Great War. This was New Zealand’s deadliest military conflict to date, with estimates ranging between circa 16,000 and 18,000 war dead. Despite this, and probably also because of it, the concept of Anzac Day itself was immediately and enduringly popular. Some of the success of Anzac Day can be placed at the intersection between public and private grief, and between individual remembrance of the war dead and civic virtues. Practically, support from the New Zealand government and from returned soldiers' groups also helped promote its success.

The Interwar Years↑

Anzac Day during the interwar period changed little in form from the war years, but modifications were made. Local councils still organised daytime events, and they often featured parades and religious services. The messages presented during the day, however, began to alter. From as early as 1922, sermons began to move away from attempting to comfort present and personal grief, instead speaking of Anzac remembrance as a duty to the dead.[4] Legal restrictions were also put in place to protect the word Anzac and to control activities that could be undertaken on Anzac Day, which only became an official government holiday in 1921.[5] In 1922 the day was made a full holiday, with all businesses closed despite complaints from employers' groups. Drinking in areas outside a recognised Returned Soldiers’ Association club was curtailed by law, along with horse-racing and other sporting activities. The veterans’ group, later to change its name to the Returned Services Association (RSA), took a leading role in lobbying government for these changes, and over time, these organisations became associated closely with Anzac Day.[6]

It was the president of the RSA, Dr. Ernest Boxer (1875-1927), who first attempted to standardise Anzac Day across the country.[7] His vision was to re-enact a wartime burial rather than hold a church service or a town meeting, and this concept was profoundly influential on future Anzac Days. Dr. Boxer proposed civilians gathering in front of a bier decorated with soldiers’ iconography, while returned soldiers marched into the space behind a gun carriage. A uniformed catafalque guard would take post around the bier, while the only speakers would be returned soldiers themselves. Mourning hymns would be sung throughout, and the service would end with ritual committal by a priest, the firing of three volleys, and the sounding of the last post. Although this service failed to become the standard used across New Zealand, elements of the service were indeed incorporated into the then-current practice of many major centres. More important was the idea of Anzac Day becoming a day of ritual mourning.

During the interwar years, and especially during the 1920s, the majority of construction on New Zealand's ubiquitous war memorials was also completed. Although now these memorials are seen as a part of the landscape, there was widespread and sometimes acrimonious debate over the form the official memorials should take.[8] One faction believed war memorials should be purely ornamental, sites of remembrance that wouldn't be effaced by an alternative use. The other faction believed money should be used to improve the lives of those whom the war affected, and war memorials should be functional, such as hospitals or town halls. As the debate raged on, local groups took the initiative. Money by public subscription was collected on an ad hoc basis to erect memorials; often these were in simple and unadorned shapes (easy for local masons to erect), or sometimes generic statues were ordered from overseas catalogues. New Zealand follows the trend of most of the rest of the world - but unlike Australia - by listing only the names of the dead on these local memorials. This practice tended to operate in tandem with local churches or schools, who often have an Honour Board listing those who served. The first stage of the New Zealand National War Memorial, built on Mount Cook in Wellington, was completed in 1934.[9]

Probably the most innovative change to Anzac Day during the interwar years occurred in 1939, the last year of peace before the outbreak of the Second World War. A permanent cenotaph had been constructed next to the Auckland War Memorial Museum, and it was here that New Zealand’s first Dawn Service was held. Copied from an Australian idea and mirroring the elements of a military funeral service, the Dawn Service has since become the most important symbolic event of all those held on New Zealand's Anzac Day.[10]

Armistice Day↑

Anzac Day was not the only day of remembrance in New Zealand during this period. Robust Armistice Day activities were held in 1919, directly celebrating the end of the Great War. Continued observances of Armistice Day in New Zealand were almost entirely overshadowed by the popularity of Anzac Day. The only element popularly observed through the inter-war period was the two minutes of silence, which was suggested by the King in 1919, and was held in common with the rest of the Empire. While official ceremonies were held to commemorate the 11th of November, popular services such as those for Anzac Day have never been a feature in practice.

Anzac Day, 1945 to 1991↑

From the Second World War until the Vietnam conflict↑

The Second World War provided Anzac Day with major challenges. The primary meaning of the day – the commemoration of those who lost their lives in the First World War – had to be reconciled with the new grief caused by the deaths occurring during the Second World War. In total, 11,900 New Zealanders were killed during the Second World War. Initially, it was by no means a given that Second World War veterans would be accorded the same status as veterans from the First World War, albeit eventually the meaning of Anzac Day did expand to include them. Further, some of the intentions that had imbued Anzac Day with its power, namely the hope that the Great War would not be repeated, were proven false.[11] Public ambivalence towards the privileges of the Returned Services Clubs on this day (their legal rights to open for activities such as serving alcohol) also took a toll on the prestige of the day. Public attendance fell into decline, despite attempts by the RSA and local councils to make it more attractive by combining services and moving them to more convenient hours. There were growing calls to make Anzac Day only a half-day long to allow other activities to take place. Finally in 1966 the RSA bowed to public pressure, and asked that the government make Anzac Day a half holiday rather than a full government holiday.[12] This change was made in 1967, but was not enough to stave off a general decline in interest for the commemorative day.

Anzac Day did remain an important part of the New Zealand calendar, but ironically its importance as a day of memory was only revived by conflict. During the 1960s, Anzac Day became a key day of protest over a range of social issues, prompted primarily by the Vietnam war. Protesters came from diverse backgrounds, including returned soldiers and professionals, however the majority were students. These protesters attempted to draw attention to modern political themes, often by laying wreaths and giving speeches. Topics included general opposition to the war in Vietnam, along with protesting crimes against women in wartime, and the cost of war on civilian lives as well as those working for the military. In response, the RSA attempted to assert a right to control messages presented at Anzac Days. This resulted in ugly scenes as protesters attempted to defy the new restrictions. This also led to tension between some RSA clubs and local councils, who continued to be the traditional organisers of these events. Probably the most famous contested Anzac Day was the 1967 Christchurch service, where veterans and audience members seized and destroyed a protest wreath laid at the war memorial, before assaulting the protesters themselves. The first alternative services to traditional Anzac Days were also organised on the same day in an attempt to create a compromise space between the two groups. These anti-war protesters were the precursor for Anzac Day being used for other social issues, such as feminist groups protesting the treatment of women during wartime, and Maori lobbyists drawing attention to their concerns over confiscated land.[13] Largely this protest activity was confined to the period between circa 1960 to 1985, and while overt protests are now no longer a prominent feature of Anzac Day, this activity did change the tenor of the day. Although modern political commentary is discouraged, speakers in the modern day are now encouraged to reflect on the social and civilian impact of the World Wars, which complements the traditional focus on dead and returned service personnel.

It was also during the conflicted Anzac Days of the Vietnam war era, that that Anzac Day reached the nadir of its popularity. Anecdotal evidence suggests that attendance previous to this period fell substantially as the day lost most of the charge given to it by close grief, by the hollowness of its previous emphasis on lasting peace, and by protesters eroding its traditional authority.[14]

During the period between 1985 to 2000, Anzac Day experienced a revival. Protest activity died away, and services attracted growing audiences. Reasons suggested for the resurgence of Anzac Day mostly link to the rise of the holiday as a part of an emerging New Zealand national identity, encouraged by government intervention intended to forge this link. Whatever the factors leading to its revitalisation, attendance figures at contemporary Anzac Days celebrations are now robust, although most participants have no personal experience with conflict. Age has also substantially reduced the numbers of veterans from the First and Second World Wars, changing the character of the gatherings.

Remembrance Day↑

While Anzac Day remained the popular day of remembrance after the Second World War, Remembrance Day was still held during November. In 1946, the services themselves were moved to the Sunday before the traditional 11 November in an effort to make it more accessible, a move met with only limited success. The decline in popularly of Anzac Day during the 1960s up until the 1980s also severely affected Remembrance Day, and this period effectively ended its role as a meaningful ritual date in the New Zealand calendar. While Anzac Day recovered strongly in the 1990s and 2000s, however, Remembrance Day has remained somewhat anaemic. Official services and the two minutes of silence have been moved back to the traditional date of 11 November, but popular observances are sporadic. The last large-scale Remembrance Day celebrations were held in 2004, and were based around the Return of the Unknown Warrior commemorations – a singular event, unlikely to be repeated. Anzac Day therefore remains unchallenged as the day New Zealanders remember their war dead.

Anzac Day between New Zealand and Australia↑

New Zealand’s Anzac Day services have been influenced and changed by Australia’s Anzac Day practice, and vice versa. The major features of Anzac Day services are similar enough between the two countries, and for this reason the day can be said to be “shared”. Each country, however, does have different parochial practices placing slightly different emphases on certain features of the day. The most obvious difference is that in Australia, the Dawn Service is often held in conjunction with a parade. This service features the surviving veterans marching through the city or town, where they are applauded by spectators. Probably, this is a relic of early Australian Anzac Days, which were often used as a tool for recruitment. Historian Chris Pugsley suggests that this feature of Australian Anzac Dat has remained because the A.I.F was an all-volunteer force, and all those who enlisted were considered worthy of praise for their great sacrifice. Australia therefore places emphasis on celebrating those who volunteered to serve and lived, as well as remembering those who died.

New Zealand, in contrast, introduced conscription in 1916 only a year after Anzac Day was established. While short marches of veterans and semi-military organisations were a feature of New Zealand Anzac Day until the 1920s, Boxer’s funerary Anzac Day format deemphasised, or even abolished, the focus placed on those who merely served. This is indicative of a wider divergence; New Zealand Anzac Day practices focus heavily on the remembrance of the dead, wounded, and damaged. It does not popularly celebrate the strength and spirit of New Zealand’s national character in the way Australian national pride is celebrated in Australian Anzac Day practices.

The second difference is that New Zealand has never emphasised the importance of Anzac Day or the “Anzac Myth” in schools, as is common in Australia. Again, unlike Australia, the New Zealand government does not provide significant funding for higher research into New Zealand Anzac practices. Most work into this field occurred during the late 1980s in unpublished academic theses. This lack of official emphasis perhaps explains why New Zealand Anzac is considered less focused on national identity relative to Australia.

Conclusion↑

Anzac Day remains the premier day of war remembrance in New Zealand. Having started off as a single day to commemorate a specific Great War campaign and organised at a local level, it has since grown to encompass the remembrance of all New Zealanders affected by war. One of the very few days of ritual recurrent in the New Zealand calendar, it has many powerful meanings attached to its performance, including having been linked a sense of New Zealand national identity. The esteem within which it is currently held has not always present; serious challenges to Anzac Day were mounted after the Second World War, including protests during the Vietnam era. However, the present day has seen these challenges overcome, or these challenges have been integrated into Anzac practices, and Anzac Day once again enjoys widespread popularity and meaning in New Zealand.

Margaret Harris, Monash University

Section Editor: Kate Hunter

Notes

- ↑ "Services at the Abbey", in: Poverty Bay Herald, 26 April 1916, p. 5.

- ↑ Worthy, Scott: A Debt of Honour. New Zealanders' First Anzac Days', in: The New Zealand Journal of History 36/2 (2002), p. 185.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 192-193.

- ↑ "Lower Hutt", Evening Post, 26 April 1922, p. 8.

- ↑ Sharpe, Maureen: Anzac Day in New Zealand; 1916-1939, in: The New Zealand Journal of History 15/2 (1981), p. 97.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 100.

- ↑ "Their Earnest Desire", Evening Post, 1 June 1920, p. 8.

- ↑ Maclean, Chris/ Phillips, Jock: The Sorrow and the Pride; New Zealand War Memorials, Wellington 1990, p.

- ↑ Ibid., p.

- ↑ Worthy: A Debt of Honour, 2002, pp. 196-197

- ↑ Robinson, Helen: Lest We Forget? The Fading of New Zealand War Commemorations, 1946-1966, in: The New Zealand Journal of History 44/1 (2010), p. 84.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 74, 78

- ↑ Locke, Elsie: Peace People, A History of Peace Activists in New Zealand, Christchurch 1992, p. 252.

- ↑ Robinson, Lest We Forget? The Fading of New Zealand War Commemorations, p. 84.

Selected Bibliography

- Crawford, John / McGibbon, Ian C. (eds.): New Zealand's Great War. New Zealand, the Allies, and the First World War, Auckland 2007: Exisle Publishing.

- Denoon, Donald / Mein Smith, Philippa / Wyndham, Marivic: A history of Australia, New Zealand, and the Pacific, Oxford; Malden 2000: Blackwell Publishing.

- Locke, Elsie: Peace people. A history of peace activities in New Zealand, Christchurch 1992: Hazard Press.

- Maclean, Chris / Phillips, Jock: The sorrow and the pride. New Zealand war memorials, Wellington 1990: GP Books.

- Pugsley, Christopher: The ANZAC experience. New Zealand, Australia and Empire in the First World War, Auckland 2004: Reed Pub.

- Robinson, Helen: Lest we forget? The fading of New Zealand war commemorations, 1946-1966, in: New Zealand Journal of History 44/1, 2010, pp. 76-91.

- Sharpe, Maureen R.: Anzac Day in New Zealand, 1916-1939, in: New Zealand Journal of History 15/2, 1981, pp. 97-114.

- Worthy, Scott: A debt of honour. New Zealanders' first Anzac days, in: New Zealand Journal of History 36/2, 2002, pp. 185-200.