Industrial War, Capitalistic War↑

War profits originated in wartime markets. Between 1914 and 1918, in order to meet the huge requirements of armaments and logistics of a fifty-two month long total war, each belligerent resorted to a mixed system. On the one hand, roughly, the state put in orders to industrialists or go-betweens. On the other hand, it provided supplies of raw materials, transport or even workers. As a result, working for national defence could basically be seen, by many industrialists in different sectors, both as a heavy task and as a serious opportunity for gain. Famous names can be named here, such as Krupp in Germany, Renault, Citroën or Schneider in France, and Vickers or Armstrong in Great Britain. However, recent historical research points out distinctions to be made depending on the industrial sector. For example, particularly in Germany, war profits reached their highest levels in heavy industry.

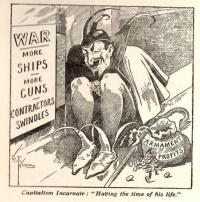

Therefore, being a key word in 19th-century industrialized Europe, “profit” took an important place in the wartime lexis. However, the period’s specificities tended to take away the word’s economical meaning – whether Marxist or not – and bring it into both political and ethical fields. In other words, profits tended to fade, to be replaced by their recipients, the profiteers, in the forefront.

From Profits to Profiteers↑

“Profit(eer)” is related to “sacrifice”, another main wartime concept – and reality, too. The idea of sacrifice, the wartime moral standard, was crucial to the attitudes of populations during the conflict. This principle must not admit any exceptions, with the result that the profiteers are denounced: both effective and imagined, war profit(eer)s quickly became unacceptable and vehement indignation could be found in many sectors of public opinion, even moderate ones. Not surprisingly, denouncement was widespread among soldiers, who appear to have been indignant at the enormous profits reaped behind the lines while they endangered their lives, as the famous “Chanson de Craonne” typifies it:

All those bigwigs living it up (...)

The whole of comrades are buried here

Just to defend these Gentlemen’s possessions"This kind of resentment knew no boundaries. As German soldiers’ scribbles on the walls of troops’ quarters or train compartments put it: "We have to fight only for the purse of others. Anything else they keep telling us is rubbish."[1] In Italy, “sharks” was the common name given to those who avoided the misfortunes of war. Newspapers, leaflets, and soldiers’ speeches, but also novels or administrative reports on public opinion: the various – but converging - echoes of profiteers’ denunciation can be seen in a wide range of historical sources. Having studied wartime caricatures in a comparative way, Jean-Louis Robert concludes that they “juxtapose the soldiers’ virtues with the mediocrity or egotism of some civilians, the cowardice of others, the incompetence or indifference of bureaucrats, the rapacity of merchants who sell to soldiers.”[2] National denunciations can nonetheless be nuanced: the turn was more political in Great Britain (continuing the traditional opposition between capital and labour), while the black-market shirkers were pointed out more in Germany. In France, the underpinning of the denunciation was civic sense, according to the republican and democratic principles.

Taxation of War Profits↑

Yet, unlike other subjects of indignation, such as spying or treason, the simple fact of making profits during the war was not legally blameworthy in itself. The combined necessity created by the increasing costs of the war and the weight of public opinion led to the promulgation of specific taxations in every country involved in the conflict:

– 23 December 1915: Excess Profits Duty (U.K.)

– 1 July 1916: Contribution Exceptionnelle sur les Bénéfices exceptionnels ou Supplémentaires réalisés pendant la Guerre (France)

– 26 July 1916: Kriegsteuergesetz (Germany)

These tax measures created the archives which allow a balanced historical approach to the war profiteers (i.e. avoiding drawing up a kind of “Great War Villains” list). The key was then to cross-match the accounting and tax sources: this allowed assessment of the level of profit and of possible fraud, the latter constituting a concrete indicator of economic mobilization. In France, this new legislation bred concern and opposition among taxpayers. Insisting on their contribution to national defence, industrial circles worried about the violation of business secrets, fiscal “inquisition”, penalization of the industry and also about the necessity not to mistake honest traders or industrialists with a minority of shady intermediaries. The employers' circles struggled in the post-war period against this form of state control, among others, both in France and in Britain. Thus, on all sides, the profiteers did not disappear after the war. In all of the belligerent countries, veterans seized this unifying theme to support their speech and interventions in the public sphere. Last but not least, resentment remained alive in Germany and Italy: the first fascist or Nazi programs were highly virulent against war profiteers.

François Bouloc, Independent Scholar

Section Editor: Emmanuelle Cronier

Notes

- ↑ Ulrich, Bernd/Ziemann, Benjamin (eds.): German Soldiers in the Great War. Letters and Eyewitness Accounts, Barnsley 2010, p. 113.

- ↑ Robert, Jean Louis: “The image of the profiteer”, in: Winter, Jay/Robert, Jean-Louis (eds.): Capital cities at war, Paris, London, Berlin, 1914-1919, Cambridge 1997, pp. 104-132, cit. p. 110.

Selected Bibliography

- Bouloc, François: Les profiteurs de guerre, 1914-1918, Paris 2008: Éditions Complexe.

- Brandes, Stuart D.: Warhogs. A history of war profits in America, Lexington 1997: University Press of Kentucky.

- Broadberry, Stephen N. / Harrison, Mark (eds.): The economics of World War I, Cambridge; New York 2005: Cambridge University Press.

- Charle, Christophe: La crise des sociétés impériales. Allemagne, France, Grande-Bretagne, 1900-1940. Essai d'histoire sociale comparée, Paris 2001: Éditions du Seuil.

- Horne, John (ed.): State, society, and mobilization in Europe during the First World War, Cambridge; New York 1997: Cambridge University Press.

- Robert, Jean-Louis: The image of the profiteer, in: Winter, Jay / Robert, Jean-Louis (eds.): Capital cities at war. Paris, London, Berlin, 1914-1919, volume 2, Cambridge; New York 1997: Cambridge University Press, pp. 104-132.