The Allied Seizure of Germany’s Pacific Island Colonies↑

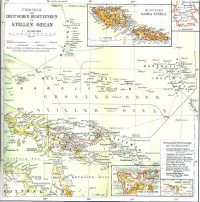

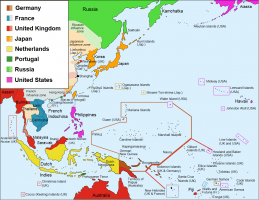

At the outbreak of World War I, Germany’s empire in the southwestern Pacific Ocean consisted of the following territories: the northeastern corner of New Guinea; the Bismarck Archipelago; the western half of Samoa; the northern half of the Solomon Islands, including Bougainville; Nauru; and Micronesia, consisting of the Mariana, Caroline and Marshall Islands. Acquired as showpieces to demonstrate the might of the emergent German Empire, the Pacific colonies were of little economic importance. Moreover, their great distance from Germany made them a strategic liability. As a result, German rule was characterized by more or less benign neglect of their indigenous subjects and the lack of any defensive preparations.

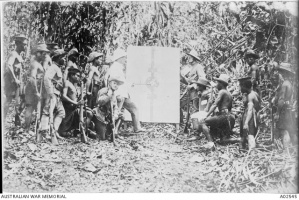

When the war broke out, the British government called on Australia to occupy New Guinea and New Zealand to take Samoa. Both Dominions, which harbored territorial ambitions in the Pacific, eagerly complied. Samoa surrendered without resistance to New Zealand on 29 August 1914. New Guinea fell shortly after a brief but sharp skirmish between the Australians and a mixed force of German and indigenous defenders at the Battle of Bitapaka near Rabaul on 11 September 1914. In October, Japanese landing forces moved quickly to occupy the Mariana, Caroline and Marshall Islands. The territories remained under the military rule of Australia, New Zealand, and Japan for the duration of the war.

Impact of the War on the Pacific Islands↑

In the territories occupied by Australia and New Zealand, German laws and currency were eventually phased out by the military administrators. At the same time, German business operations, most notably copra production and phosphate mining, were sequestered and then taken over by Australian and New Zealand companies, which intensified the economic exploitation of the Pacific Islands. The growing demand for labor in these enterprises led to the forcible recruiting and employment of the indigenous population. Resistance to forcible recruitment was often harshly punished using methods such as punitive expeditions by the military and police and the employment of corporal punishment. Thanks largely to the incompetence of medical officers in failing to implement a quarantine, the Spanish influenza struck the Pacific Islands in November 1918. The populations of Nauru and Samoa in particular were devastated as a result. In the Japanese-administered territories, the indigenous population was subjected to a heavy-handed policy of assimilation in the form of replacing local culture with a new and wholly Japanese identity.

In addition, Pacific Islanders from Allied-controlled territories also served in the war. A small number of Samoans, Tongans, Fijians, and Papuans were recruited into British service and eventually made their way to battlefields in Europe. Resentment against harsh French colonial rule in general, exacerbated by especially heavy wartime levies of manpower for labor and military service in France, sparked a revolt among the indigenous Kanak population of New Caledonia in 1917. By the time the French authorities succeeded in extinguishing the revolt in 1918, the conflict had claimed several hundred lives.

The Post-war Settlement and the Pacific Islands↑

The fate of the German Pacific Islands was largely an afterthought that evoked little interest among the statesmen assembled at the Paris Peace Conference. Although the Germans had entertained some hope of the restoration of their Pacific colonies, vigorous lobbying on the part of Australia, New Zealand, and Japan led to preservation of the wartime status quo in the form of League of Nations mandates. Australia was awarded the former German New Guinea, the Bismarck Archipelago, Nauru, and the northern half of the Solomon Islands. German Samoa became a New Zealand mandate, and Japan was awarded the mandate of the former German colonies north of the Equator, namely the Mariana, Caroline, and Marshall Islands. The Pacific Islands remained in the hands of those nations until World War II.

John Jennings, United States Air Force Academy

Section Editor: Mark E. Grotelueschen

Selected Bibliography

- Hiery, Hermann: The neglected war. The German South Pacific and the influence of World War I, Honolulu 1995: University of Hawaii Press.

- Muckle, Adrian: Specters of violence in a colonial context. New Caledonia, 1917, Honolulu 2012: University of Hawaii Press.

- Peattie, Mark R.: Nan’yō. The rise and fall of the Japanese in Micronesia, 1885-1945, Honolulu 1988: University of Hawaii Press.