Introduction↑

The First World War deeply affected Australian women, even though they were 20,000 kilometres away from the major war zones. They mobilised for war in a number of ways: as nurses, doctors and other volunteers in the battle zones; as workers, both paid and unpaid, on the home front; as protagonists in war-related political and industrial struggles and as agents of remembrance. While the official war histories included passing reference to these activities, academic scholarship on women’s wartime mobilisations is largely a product of the decades since the 1980s. Much of this research has focused on the opposition to war and conscription, although nurses have also received attention and labour historians in particular have analysed patriotic women’s activities.[1]

Working in the Battle Zones↑

Nearly 3,000 Australian women served as nurses during the First World War. Most of these served in the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS), although a dozen are also known to have served as Royal Australian Navy Nurses. The rest joined other Allied organisations such as the Red Cross (French, British and Australian), Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service, Territorial Force Nursing Service, Lady Dudley’s Australian Voluntary Hospitals, Salvation Army Nurses and the New Zealand Army Nursing Service.[2] Approximately forty women served as masseuses, twenty-nine of these in the AANS. Female doctors, whose services were refused by the Australian military, had been accepted in British army nursing since the war against the Boers, despite lingering reservations amongst some senior military officials about their suitability for active service. Twenty-three Australian women doctors made their own way to Europe to join organisations such as the Scottish Women’s Hospitals, the Endell Street Military Hospital, Royal Army Medical Corps and the French Red Cross, one of whom, Dr. Phoebe Chapple (1879-1967), became the first woman doctor to be awarded the British Military Medal.[3] A further 120 Australian women are known to have served in the Voluntary Aid Detachments established by the Red Cross.[4]

Australian women had a variety of motives for heading off to war, just as did the men who enlisted. Patriotism and a sense of duty featured strongly in their own explanations of why they signed on – a strong feeling that they needed to “do their bit” for their country and the Empire. Many also wanted to be close to their menfolk, whether relatives or friends. And like the men, most were excited by the opportunity that the war presented for travel, adventures and perhaps even romance.[5]

Nurses embarked on the first convoy of ships that sailed to Egypt in November 1914 and, like their male comrades, saw their first action at Gallipoli in April of the following year. Confident of a quick campaign, the Allied command had made little provision for the wounded. For many hours after the landing on 25 April 1915, the wounded lay exposed on the narrow beaches, showered by enemy gunfire. Those who survived were laid out on transports and slowly towed away to safety. Throughout the Gallipoli campaign, the nurses waited to receive the wounded, stationed on hospital ships off the shore or in the hospital camps of Alexandria and Malta, and later on Lemnos Island.

Conditions were particularly bad on the hospital ships in the early weeks of the conflict, with lack of staff and medical provisions making the task of providing adequate care impossible. Each time there was a major battle, medical facilities quickly became overwhelmed with the wounded and dying. Conditions on Lemnos were also very bad, with inadequately equipped and underfed staff living in flimsy tents for most of their stay, subject to freezing conditions and gale-force winds. There were too few staff to cope with the “invasions” of patients during offensives on Gallipoli and a majority of the medical staff succumbed to a severe form of dysentery that plagued the island.[6] These conditions were good preparation for those nurses who went on to the Western Front after the withdrawal from Gallipoli at the end of 1915.

In France and Belgium, those stationed at “casualty clearing stations” faced extremely difficult and sometimes dangerous conditions, exposed to gas and bomb attacks. Conditions in the base hospitals behind the lines were better, as they were in England. Most nurses experienced a variety of these assignments, but all were exposed to the physical and mental strain of dealing with the huge number of casualties generated by the battles of 1916-1918. The fact that so many nurses had close personal relationships with men who were severely injured or killed added to the strain.

Those who joined the AANS had no choice but to serve for the duration of hostilities, unless they got married. Many served throughout the conflict. Some forty-three Australian women died serving overseas, twenty-six of whom were nurses. A handful were killed by enemy attack – including four stewardesses who died when the ship on which they were serving hit a mine – but most died from the effects of illness and exhaustion.[7]

Australian nurses also served on the “forgotten frontiers” well away from the main action on the Western Front. 500 Australian army nurses were sent to India and Mesopotamia and 300 to Salonika. The women deeply resented these postings. Having joined up to help the Australian war effort, they found themselves nursing almost every imaginable nationality but their own. They also dealt mainly with the sick rather than the wounded. For these nurses, the war often meant hunger and isolation as well as discomfort and exhaustion: there were no outings for them to Paris or leaves in London to provide relief from their working lives.[8]

Regardless of where they served, Australian army nurses chafed under their anomalous status within the military. Although recognised as “honorary officers”, they were not issued with badges of rank until 1916 and were never paid at male officers’ rates (unlike Canadian nurses, whom they often worked alongside).[9]

After the armistice, most nurses and other women volunteers returned to Australia. For many, their health never recovered from the physical and emotional stresses of wartime service. Nurses, however, found their wartime experiences led to a new confidence in their abilities and new understanding of their role as workers. During the worst battles of the war on the Western Front, they had been called upon to do work previously reserved for men, such as surgery and anaesthetics, although men reclaimed this territory as soon conditions allowed.[10] After the war, nurses formed union-like organisations whose membership was dominated by those who were “ex-AIF”.[11]

Work on the Home Front↑

Patriotic Fundraising↑

Those women who served overseas were not the only ones willing to do their bit for the war effort. Throughout the war, hundreds of Australian women wrote to the military authorities offering their services in Europe. They volunteered to work in any capacity – as ambulance drivers, cooks, hospital orderlies or office workers. By January 1917, the Australian Women’s Service Corps boasted 700 members. The Australian Lady Volunteers, formed in Sydney in September 1914, aimed to become “real rifle women and real soldiers”. In Melbourne, 1,500 women from forty-two organisations gathered at the town hall in July 1915 to urge the Federal Government to open bureaus where women could register for service to the Empire.[12]

The Australian Imperial Force was adamant that it did not require the services of women; war was men’s business and women would be “a liability, not an asset” anywhere near the front.[13] Prevailing notions of appropriate gender roles cast women as the ones who “kept the home fires burning” while they waited for the return of their warrior menfolk. The only grudging exception was the case of nurses, who could still be seen as fulfilling the womanly roles of compassion and care.

But for many women, the passivity this implied was unpalatable, and they sought more active ways to contribute to the war effort through raising funds and producing comforts for the troops. Throughout the war, an estimated 10,000 patriotic clubs, societies and sewing circles sprang up to knit socks, vests, mufflers and mittens, pack parcels of cakes, magazines, medical and recreational equipment, kitchen appliances and tobacco and write encouraging letters to men they had never met. It amounted “to a completely new sector of the economy” and was arguably central to the war effort.[14]

The largest single society was the Red Cross. An Australian branch of the British Red Cross was formed less than two weeks after Australia entered the war. Within months, New South Wales alone boasted over 300 branches. By 1918 there were 2,200 branches across Australia involving some 82,000 women – at a time when just over 55,000 women were engaged in paid work.[15] Over the course of the war, this army of volunteers sent nearly 400,000 Red Cross parcels to Europe, containing 320,389 pyjamas, 457,311 shirts, 130,842 pairs of underpants, 1,163,049 pairs of socks, 142,708 mufflers, 83,047 pairs of mittens and 3,000 cases of linen for surgical dressings and bandages. In addition, the Western Front received 10,500,000 cigarettes, 241,232 ounces of tobacco, 94,007 toothbrushes, 57,691 pipes, 65,000 tins of cocoa-and-milk and coffee-and-milk, and 869 Primus stoves.[16] Mosquito nets, sandbags, “thrillers of the best kind” and “Bibles and improving literature” also made their way across the seas. In Sydney alone, 100 women at the “War Chest” worked all week, every week, just sorting, packing and dispatching parcels.[17]

All this activity required a formidable amount of organisation. The Red Cross depots modelled themselves along quasi-military lines, with clear lines of command from the “director of the depot” to her “chief lieutenants” down to the “large band of helpers” in the store and “regiments” of sewers, knitters and fundraisers in the suburbs and countryside. The organisation of the work also employed the latest ideas from the “scientific management” of industry, the work being “so subdivided and classified ... that every worker arriving in the room knows exactly where to commence without any instructions”.[18] Nor were these volunteer efforts directed solely at comforts for the Australian troops. In the first year of the war, South Australia’s Red Cross raised over 13,000 pounds for the Belgium Fund, money intended for the relief of refugees in Europe.[19]

In addition to the Red Cross, hundreds of organisations sprang up across the country in the early years of the war, usually led by members of the social and political elites such as Eva Hughes (1856-1940) and staffed by middle-class women volunteers. These included the Lady Mayoress’ Patriotic League (Victoria), the Citizens’ War Chest (New South Wales), the League of Loyal Women (South Australia), the Queensland Patriotic Fund, the “On Active Service” Fund (Tasmania), the Victorian League of Western Australia, and the Belgian Relief Committees. Many of these organisations joined together in 1916 to form the Australian Comforts Fund with a view to providing a more coordinated approach to the national war effort.[20]

While fundraising and despatching comforts was the major focus of all this activity, so too was the provision of social events for the soldiers and their families. In December 1916, South Australia’s League of Loyal Women entertained 1,000 mothers and 3,200 children at a Christmas party on the Adelaide oval. There were fourteen trees, each decorated with regimental colours and laden with homemade toys.[21] And throughout the war groups like the Cheer Up Society resolved “to make the path of the soldier as he left Australia as bright and easy as possible”.[22]

Such occasions demanded an enormous amount of labour as well as money. Entertaining over 1,000 guests meant washing up around 3,000 pieces of crockery and 4,000 pieces of cutlery, keeping women at the sink until well after the guests had left, with “girls” commonly working thirteen-hour shifts for years, reportedly “smilingly and uncomplainingly”.[23] The Cheer Up Society hoped that such occasions would not only brighten the mood of the departing troops but also provide them with “clean, healthy amusement” as an alternative to the pubs and brothels of the city. It also hoped that the memory of Australia’s wholesome womanhood would provide a moral compass for fighting men amidst the temptations of overseas service.[24]

As the war wore on, the role of these societies necessarily changed. While still involved in bidding the troops farewell, increasingly they were occupied with welcoming the crippled and wounded – the “shattered and nerve-stricken wrecks” – who returned home. This was a much harder task, stretching the financial and personal resources of the Society.[25] The facilities and care provided by women clearly helped such veterans. Mary Booth (1869-1956) reported with satisfaction that her Soldiers’ Club in Sydney had “the pleasure of watching many of these men, highly strung and overwrought, gradually regaining health and self-control and settling down to civil life”.[26] The Red Cross and other patriotic charities also played a crucial role in the repatriation of servicemen through supplementing their inadequate pensions,[27] while in Sydney the Australian Women’s Service Corps felled timber, cleared brushwood and hauled stone in order to prepare blocks of land for returned servicemen to farm.[28]

While thousands of women were thus engaged in volunteer work in Australia, some Australian women travelled to Europe, where they contributed to war-related work in a variety of ways. Vera Deakin (1891-1978), the daughter of former Prime Minister Alfred Deakin (1856-1919), formed the Australian Red Cross Wounded and Missing Inquiry Bureau in October 1915. This bureau undertook the formidable task of trying to identify the fate of soldiers who went missing in battle, corresponding with and interviewing former comrades who might have been witnesses and writing to relatives with any news. By the end of the war 22,000 Australians were still listed as missing, and 4,000 reports a month were being sent back to Australia. The sensitivity with which these inquiries were handled demanded an enormous emotional as well as physical labour, and played an important part in reconciling families to the loss of their loved ones.[29] Other Red Cross workers, such as Mary Chomley (1872-1960), devoted their energies to the welfare of prisoners of war,[30] while the enterprising Lizzie Armstrong provided guided tours of London and surrounding sites for soldiers on leave when she was not working as a masseuse.[31]

All of these women had the resources to fund their patriotic projects, but it was not only middle-class and elite women whose voluntary labour supported the war effort, although invariably they provided the leadership of the various patriotic societies.[32] For working-class women, war work usually added to already heavy workloads, whether paid or unpaid. Australia in general did not witness the influx of women into the workforce that combatant nations closer to the front saw: distance from the combat zones and wartime hazards to shipping meant that Australia was not called upon to any great extent for war supplies. Many sectors of the economy experienced a downturn in demand for workers.

However, sections of the economy directly engaged in war production did see more women employed on a regular basis – particularly in clothing, boot and small arms factories. And many female-dominated workplaces formed special working bees to raise money and make comforts for the troops. Of these, the most famous were the “Lucas Girls” of Ballarat and the “Khaki Girls” of Melbourne. Both groups were drawn from clothing workers, the Commonwealth Government Clothing Factory (home of the “Khaki Girls”) making uniforms for the troops. Several days a week, 200 women working at the Government Clothing Factory returned to their benches in the evenings after a full day’s work and spent several hours making up shirts and warm underclothing for the troops. The cost of the material was defrayed out of a fund contributed to by the “girls” themselves and their friends.[33]

Their contribution did not stop there, however. The Khaki Girls organised themselves into three branches – a Bugle Band, a Physical Culture Squad and a Rifle Squad – each of which had its own distinctive paramilitary uniform. These groups devoted their time to drilling and performing in order to raise funds and assist the recruiting effort, travelling throughout rural Victoria where they competed in football matches against the Lucas Girls in Ballarat.

The overt military style of the Khaki Girls was symptomatic of a more general “militarisation of charity” during the war years. In a similar vein, a procession described as a “Crusade of Mercy” on Red Cross Button Day in 1918 consisted of an “army of matrons and maids” led by a band of mounted women, “symbolising the Crusaders of old time who rode forth to free a nation from oppression”.[34] For all its internationalist and humanitarian rhetoric, the Red Cross took on a distinctly nationalist flavour as the war progressed.

Participating in all this activity provided an outlet for women denied other avenues of contributing to the war effort available to their sisters closer to the front. But it also had more personal and individual meanings for the women themselves, providing companionship and solace as they endured the long years of waiting and anxiety, and the all too frequent news of the death or injury of their menfolk. And it also provided opportunities for socially sanctioned entertainment in an environment where activities not directed towards wartime fundraising were considered frivolous, if not downright unpatriotic.

Conscription, Industrial Struggle and Food Riots↑

The patriotic women who raised funds and produced comfort parcels for the war effort were also active in recruiting men for the front. Sometimes they used subtle forms of feminine persuasion to influence men to enlist, and other times they employed more overt forms of pressure, such as sending white feathers as symbols of cowardice to men they thought should be in uniform. Women played an important role in the enlistment marches that wound their way through rural Australia seeking recruits after the terrible losses at Gallipoli: they provided meals and entertainment, spoke at public meetings and cheered on the marchers.

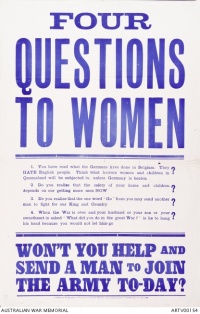

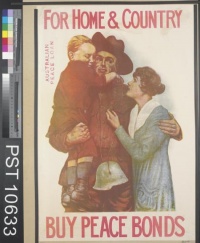

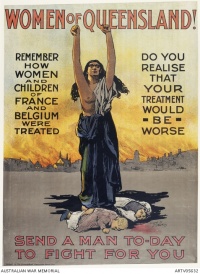

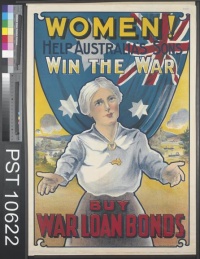

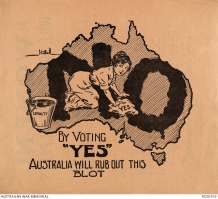

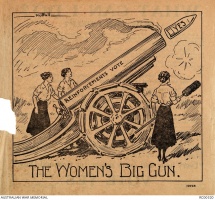

Securing volunteers was vital if Australia was to continue to contribute to the fighting forces, as Australia was the only combatant nation that did not conscript troops. It was also the only country that sought the public’s view on this matter. When the Federal Government decided to hold a plebiscite on conscription, patriotic women’s support for the recruitment effort took on more political dimensions. Tens of thousands of women mobilised in support of the “Yes” case, advocating compulsion where voluntarism had failed. Unlike most of their sisters in other combatant nations, white Australian women were eligible to vote on the same terms as men. Their votes were seen as crucial to the result and women became both the targets and the agents of propaganda in unprecedented ways.[35]

The leaders of the women’s pro-conscription campaigns tended to be the same type as those who led the other patriotic groups discussed earlier: middle-class women with strong connections to conservative political groups who believed implicitly in the righteousness of the imperial cause. Their wartime activism was a continuation of pre-war organisation for conservative, Imperial causes, but became much more public as patriotic women took to speaking platforms in ways that would not have been contemplated in peacetime.[36] This wartime experience of organisation and advocacy in turn laid the basis for a greater public role for conservative women after the war.[37]

At times, women’s support for conscription erupted into physical attacks on their opponents. At a public meeting in 1917, an angry crowd of women attacked a speaker, Margaret Thorp (1892-1978), a Queensland Quaker and leader of the Brisbane Women’s Peace Army. They dragged her to the floor, “punched and scratched, rolled on the floor, kicked and punched, and scratched again.” Pandemonium broke out among the female crowd as the 230-strong conscription supporters battled with the twenty to thirty “antis”, slapping faces, pulling hair, tearing clothes and engaging in “actual fisticuffs”. Thorp’s repeated attempts to ascend the platform were met by renewed violence against her and her handful of supporters, culminating in Thorp and two others being physically thrown from the hall.[38]

The Women’s Peace Army that Thorp represented was the most visible and influential of the women’s anti-conscription organisations. Formed in 1915, the Peace Army grew out of a Melbourne feminist organisation, the non-party Women’s Political Association, whose members found themselves divided over support for the war. Socialist-feminists quickly fell in behind the flamboyant and charismatic leadership offered by the WPA, arguing that the war itself was a fight between rival national groups of capitalists in which workers were merely the cannon fodder. Women, they argued, should work for peace as they were the “lifegivers of the world” and thus naturally more peaceful and nurturing than aggressive males.[39]

The Women’s Peace Army and other left-wing groups (such as the International Workers of the World, the No Conscription Fellowship and the Militant Propagandists of the Labour Movement) were joined in their opposition to the war and conscription by men and women whose objections were based on religious conviction. Most prominent amongst these were the Quakers and the followers of the Australia Church in Melbourne, who formed the Sisterhood of International Peace in March 1915.

All these groups joined forces to campaign against conscription. They arranged thousands of meetings across Australia, with speakers travelling from state to state, addressing crowds on street corners and in huge open-air venues. The women who undertook these public speaking engagements, as we have seen, faced violence from other women, but they were also frequently assaulted by male opponents, usually soldiers.[40]

As the two conscription referenda divided Australia virtually down the middle, war-fuelled industrial turmoil, particularly in New South Wales, drew women into conflict as protagonists on both sides. The divisions fell along the same lines as support or opposition to conscription. In Melbourne, unemployment and food shortages led to suspicions that capitalists were resorting to economic conscription and profiteering where the attempt at legal compulsion has failed. Public demonstrations led by Adela Pankhurst (1885-1961) – daughter of the British suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst (1858-1928) – and Jennie Baines (1866-1951), turned into riots in August 1917.[41]

Conclusion: Mobilising to Remember↑

Women’s efforts were central to the recruitment, support and rehabilitation of the troops, but they were also a key part of the process whereby Australians remembered and commemorated the war dead. The Lucas Girls did not just raise money for comforts: they also raised the staggering sum of 10,600 pounds towards the cost of trees and plaques for an Avenue of Honour.[42] Nor was this an isolated case: right across the country, women were at the centre of commemorations of the war dead. They raised the money to build the monuments and practical memorials (like libraries and parks); they helped lobby local governments; they made the wreaths for the ceremonies and they gathered each year to remember the men who were lost. And they engaged in the post-war contests over the appropriate forms that commemoration should take.[43] Ironically, this army of female volunteers were themselves omitted from these memorials to Australia’s war sacrifice.[44] Once the AIF returned, the intimate ceremonies focused on the wharves or local memorials that women had orchestrated were replaced by massed processions of veterans down city streets. In Melbourne, women were initially even excluded from the Dawn Service.[45] A century later, historians are still uncovering and reassessing the full extent of Australian women’s mobilisations for war.

Rae Frances, Monash University

Section Editor: Peter Stanley

Notes

- ↑ The following books included chapters on women’s patriotic activities: Adam-Smith, Patsy: Australian Women at War, Melbourne 1984; Scates, Bruce / Frances, Raelene: Australian Women and the Great War, Cambridge 1997. Scates, Bruce: The Unknown Sock Knitter. Voluntary Work, Emotional Labour, Bereavement and the Great War, in: Labour History 81 (2001), pp. 29-51 also provides a sophisticated analysis of women’s patriotic war work. Beaumont, Joan: Whatever happened to Patriotic Women, 1914-18, in: Australian Historical Studies 31/115 (2000), pp. 273-287 makes the valid point that more attention has been given to those women who opposed the war and conscription than to those who supported it, but her analysis, repeated in Beaumont, Joan: Broken Nation. Australians in the Great War, Sydney 2013, pp. 99-101, overlooks these key contributions to the historiography. Melanie Oppenheimer has made a major contribution to the history of Australia’s volunteer patriotic labour. See Oppenheimer, Melanie: Red Cross VADs. A History of the VAD Movement in New South Wales, Sydney 1999; Oppenheimer, Melanie: “The Best PM for the Empire in War”? Lady Helen Munro Ferguson and the Australian Red Cross Society 1914-1920, in: Australian Historical Studies 33/119 (2002), pp. 108-134; Oppenheimer, Melanie: “Fated to a Life of Suffering.” Graythwaite, the Australian Red Cross and Returned Soldiers, 1916-19, in: Crotty, Martin / Larsson, Marina (eds.): Anzac Legacies. Australians and the Aftermath of War, Melbourne 2010, pp. 18-38; Oppenheimer, Melanie: The Power of Humanity. 100 Years of Australian Red Cross, Melbourne 2014.

- ↑ The exact number is not known. The official history puts the number in the Australian Army Nursing Service at 2,139. Kirsty Harris currently has 2,700 AANS nurses on her database. Butler, A.G.: The Official History of the Australian Army Medical Services in the War of 1914-1918, vol. III, Canberra 1943, p. 543; Harris, Kirsty: Red Rag to a British Bull? Australian trained nurses working with British nurses during World War One, in: Darian-Smith, Kate et al. (eds.): Exploring the British World. Identity – cultural production – institutions, Melbourne 2004, p. 126. For Red Cross nurses, see Oppenheimer, Melanie: Gifts for France. Australian Red Cross Nurses in France, 1916-19, in: Journal of Australian Studies 39 (1993), pp. 65-78. For units in which Australians served overseas, see Baker, Jennifer: The Forgotten Service of Australian Women during WW1. A Summary of Units in which Australian Women Served in during WW1, issued by Looking for Evidence, online: https://sites.google.com/site/archoevidence/home/ww1australianwomen, (retrieved: 1 May 2014).

- ↑ Bassett, Jan: Guns and Brooches. Australian Army Nurses from the Boer War to the Gulf War, Melbourne 1992, pp. 19f; Baker, Jennifer: Australian Women Doctors who served in WW1, issued by Looking for Evidence, online: https://sites.google.com/site/archoevidence/home/ww1womendoctors (retrieved: 1 May 2014); Blanch, Craig: Dr Phoebe Chapple. The first woman doctor to win the Military Medal, issued by Australian War Memorial, online: http://www.awm.gov.au/blog/2009/06/30/dr-phoebe-chapple-the-first-woman-doctor-to-recieve-the-military-medal/, (retrieved: 1 May 2014).

- ↑ Baker, Forgotten Service 2014.

- ↑ Scates / Frances, Australian Women 1997, p. 6.

- ↑ Butler, Janet: Kitty’s War. The Remarkable Wartime Experiences of Kit McNaughton, Sydney 2013, p. 63.

- ↑ Baker, Jennifer: Australian Women who gave their lives in WW1, issued by Looking for Evidence, online: https://sites.google.com/site/archoevidence/home/ww1-australian-women-deaths (retrieved: 1 May 2014).

- ↑ Oppenheimer, Melanie: Oceans of Love. Narrelle – An Australian Nurse in World War I, Sydney 2006, chapters 7 and 8; Scates / Frances, Australian Women 1997, pp. 28-32; Bassett, Jan: Guns and Brooches. Australian Army Nurses from the Boer War to the Gulf War, Melbourne 1992, p. 79.

- ↑ Bassett, Guns and Brooches 1992, pp. 55-60; Butler, Kitty’s War 2013, pp.66f;

- ↑ Scates / Frances, Australian Women 1997, pp. 21, 26; kitty, pp. 134-5. Kitty McNaughton was also one of the few nurses given the opportunity to work in the new area of plastic surgery, reconstructing the faces of badly wounded soldiers. Butler, Kitty’s War 2013, p. 209.

- ↑ Butler, Kitty’s War 2013, p. 71; Law, Glenda: “I never liked trade unionism.” The development of the Royal Australian Nursing Federation, Queensland Branch, 1904-45, in: Windschuttle, Elizabeth (ed.): Women, Class and History. Feminist Perspective on Australia 1788-1974, Sydney 1980, p. 206; Trembath, R. / Hellier, D.: All Care and Responsibility. A History of Nursing in Victoria, 1850-1934, Melbourne 1987, p. 124.

- ↑ Bassett, Jan: “Ready to Serve.” Australian Women and the Great War, in: Journal of the Australian War Memorial 2 (1983), pp. 8f.

- ↑ AIF Despatches, cited in “Women War Workers,” Jensen Papers, Accession No. MP 598/30, Department of Supply, Item 15, National Archives of Australia, Victoria.

- ↑ McKernan, Michael: The Australian People and the Great War, Sydney 1984, pp. 66f.

- ↑ Beaumont, Broken Nation 2013, pp. 94f. For the early history of the Red Cross see Moorehead, Caroline: Dunant’s Dream. War, Switzerland and the History of the Red Cross, London 1998; also Hutchison, John: Champions of Charity. War the Rise of the Red Cross, Oxford 1996; for the Australian Red Cross, see Oppenheimer, The Power of Humanity 2014; Stubbings, Leon: Look What You Started Henry! A History of the Australian Red Cross, 1914-28, Melbourne 1992; Oppenheimer, Red Cross VADs 1999; Oppenheimer, Melanie: Volunteers in Action. Voluntary Work in Australia, 1939-45, PhD thesis, Macquarie University 1997, contains a chapter on women’s voluntary work in World War I.

- ↑ Scott, Official History, vol. XI, pp. 703, 705f; Scates / Frances, Australian Women 1997, pp. 46ff; Scates, Unknown Sock 2001, pp. 29-51.

- ↑ Scates, Unknown Sock Knitter 2001, p. 33.

- ↑ ‘Packaging and Receiving Depot,’ Sydney Mail, 2 August 1916, cited in Scates, Unknown Sock Knitter 2001, p. 33.

- ↑ Red Cross Society: The Red Cross and Belgium Fete Book, Adelaide 1915, p. 9.

- ↑ Beaumont, Broken Nation 2013, p. 95.

- ↑ Red Cross Record, January 1917.

- ↑ Scates / Frances, Australian Women 1997, p. 58.

- ↑ Mills, Frederick J.: Cheer Up. A Story of War Work, Adelaide 1920, p. 107.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 58f.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 71, 154.

- ↑ Circular by Mary Booth outlining the functions of the Soldiers’ Club, dated 14 April 1917, cited in Scates, Unknown Sock Knitter 2001, p. 38. However, many others did not shake off their war experiences so easily and the same Soldiers’ Club occasionally had to contend with violent brawls that broke out amongst the returned men. Scates, Unknown Sock Knitter 2001, pp. 38f.

- ↑ Lindstrom, Richard: The Australian Experience of Psychological Casualties in War, 1915-1939, Ph.D. thesis, Victoria University of Technology, 1997, pp. 148ff, online: http://vuir.vu.edu.au/15400/1/Lindstrom_1997_compressed.pdf (retrieved: 18 November 2014; Lloyd, Clem / Rees, Jacqui: The Last Shilling. A History of Repatriation in Australia, Melbourne 1994, pp. 26-29.

- ↑ Scates / Frances, Australian Women 1997, p. 62.

- ↑ Scates, Bruce: Return to Gallipoli. Walking the Battlefields of the Great War, Cambridge 2006, pp. 6-9; Scates, Unknown Sock Knitter 2001, pp. 39-43.

- ↑ Kildea, Josephine: Miss Chomley and Her Prisoners. The Prisoner of War Experience and the Australian Red Cross Society in the Great War, Bachelor of Arts (Honours) thesis, University of New South Wales, 2006.

- ↑ Scates, Return to Gallipoli 2006, p. 73; Scates, Bruce / Wheatly, Rebecca / James, Laura: 100 Stories, issued by Monash University, online: http://artsonline.monash.edu.au/anzac-remembered/100-stories-project/ (retrieved: 1 May 2014).

- ↑ Although men were often the nominal office-bearers, it was usually women who actually led these groups. An exception was the NSW Lord Mayor’s Partiotic Fund which excluded women from its executive committee, see Oppenheimer, Melanie: Alleviating Distress. The Lord Mayor’s Patriotic Fund in New South Wales, 1914-1920, in: Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society 81/1 (1995), p. 92.

- ↑ Argus, 28 July 1917, p. 8. See also Bassett, Jan / Barnard, Lyla: Khaki Girl, in: Lake, Marilyn / Kelly, Farley (eds.): Double Time. Women in Victoria 150 Years, Ringwood 1985, p. 271; Scates / Frances, Australian Women 1997, p. 56.

- ↑ Red Cross Record, October 1918.

- ↑ Shute, Carmel: “Blood Votes” and the “Bestial Boche.” A Case Study in Propoganda, in: Hecate 2/2 (1976), pp. 7-22; Shute, Carmel: Heroines and Heroes. Sexual Mythology in Australia, 1914-18, in: Damousi, Joy / Lake, Marilyn: Gender and War. Australians at War in the Twentieth Century, Melbourne 1995, pp. 23-42.

- ↑ Smart, Judith / Hughes, Eva: Militant Conservative, in: Lake, Marilyn / Kelly, Farley (eds.): Double Time. Women in Victoria 150 Years, Ringwood 1985, p. 183.

- ↑ Scott, Joanne: “Generic Resemblances”? Women and Work in Queensland, 1919-1939, PhD thesis, University of Queensland 1996.

- ↑ Daily Standard, 10 July 1917, cited in Evans, Raymond: “All the passion of our womanhood.” Margaret Thorp and the Battle of the Brisbane School of Arts, in: Damousi / Lake, Gender and War 1995, p. 240. See also Summy, Hilary: Margaret Thorp and the Anti-Conscription Campaign in Brisbane 1915-17, in: Hecate 32/1 (2006), pp. 59-76.

- ↑ The WPA president was the beautiful, charming and eloquent Vida Goldstein (1869-1949) who had already achieved international fame as the first woman in the English-speaking world to stand for parliamentary election. Secretary Adela Pankhurst was the daughter of English suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst and shared her talent for political organisation. Treasurer Cecilia John’s (1877-1955) famous contralto voice never failed to stir an audience when she burst into her extensive repertoire of anti-conscription and peace songs. Bomford, J.: That Dangerous and Persuasive Woman. Vida Goldstein, Melbourne 1993; Gowland, Patricia: John, Cecilia Annie (1877-1955), in: Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol. 9, Melbourne 1983; Damousi, Joy: An Absence of Anything Masculine. Vida Goldstein and Women’s Public Speech, in: Victorian Historical Journal 79/2 (2008), pp. 251-264.

- ↑ Evans, All the Passion 1995; Summy, Margaret Thorp 2006; Damousi, Joy: Socialist Women and Gendered Space. Anti-Conscription and Anti-War Campaigns 1915-18, in: Damousi / Lake, Gender and War 1995, pp. 254-273; Damousi, Joy: Women Come Rally. Socialism, Communism and Gender in Australia 1890-1955, Melbourne 1994; Smart, Judith: The Right to Speak and the Right to be Heard. The Popular Disruption of Conscriptionist Meetings in Melbourne, 1916, in: Australian Historical Studies 23/92 (1989), pp. 201-219.

- ↑ Scates / Frances, Australian Women 1997, pp. 96ff; Smart, Judith: Feminists, Food and the Fair Price. The Cost-of-Living Demonstrations in Melbourne. August-September 1917, in: Damousi / Lake, Gender and War 1995, pp. 274-301.

- ↑ Scates / Frances, Australian Women 1997, p. 56.

- ↑ Scates / Frances, Australian Women 1997, pp. 114-121.

- ↑ Inglis, Ken: Men, Women and War Memorials, in: Daedalus 116 (1987), p. 35. Nurses were listed on war memorials alongside men who served in the Australian military, but women who worked in voluntary organisations were only commemorated in tablets located inside or outside town halls. A national memorial to Australia’s military nurses was unveiled in Canberra in 1999.

- ↑ Scates, Unknown Sock Knitter 2001, pp. 44f; Scates, Bruce: A Place to Remember. A History of the Shrine of Remembrance, Melbourne 2009, pp. 233-236.

Selected Bibliography

- Adam-Smith, Patsy: Australian women at war, Melbourne 1984: Nelson.

- Barker, Marianne: Nightingales in the mud. The digger sisters of the Great War, 1914-1918, Sydney 1989: Allen & Unwin.

- Bassett, Jan: Guns and brooches. Australian army nursing from the Boer War to the Gulf War, Melbourne 1992: Oxford.

- Beaumont, Joan: Broken nation. Australians in the Great War, Crow's Nest 2013: Allen & Unwin.

- Butler, A. G.: The official history of the Australian Army Medical Service in the war of 1914-18, 3 volumes, Melbourne 1930-1945: Australian War Memorial.

- Butler, Janet: Kitty's war. The remarkable wartime experiences of Kit McNaughton, Brisbane 2013: University of Queensland Press.

- Damousi, Joy: Marching to different drums. Women’s mobilizations 1914-39, in: Saunders, Kay / Evans, Raymond (eds.): Gender relations in Australia. Domination and negotiation, Sydney; Fort Worth 1992: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, pp. 350-375.

- Damousi, Joy / Lake, Marilyn (eds.): Gender and war. Australians at war in the twentieth century, Cambridge; New York 1995: Cambridge University Press.

- Goodman, Rupert D.: Our war nurses. The history of the Royal Australian Army Nursing Corps, 1902-1988, Bowen Hills 1988: Boolarong Publications.

- Harris, Kirsty: More than bombs and bandages. Australian Army nurses at work in World War I, Newport 2012: Big Sky Publishing.

- McKernan, Michael: The Australian people and the Great War, Melbourne 1980: Thomas Nelson.

- Oppenheimer, Melanie: The power of humanity. 100 years of Australian Red Cross 1914-2014, Sydney 2014: HarperCollins.

- Oppenheimer, Melanie: ‘The best P.M. for the empire in war'? Lady Helen Munro Ferguson and the Australian Red Cross Society, 1914–1920, in: Australian Historical Studies 33/119, 2002, pp. 108-134, doi:10.1080/10314610208596204.

- Oppenheimer, Melanie: Gifts for France. Australian Red Cross nurses in France, 1916-19, in: Journal of Australian Studies 39, 1993, pp. 65-78.

- Oppenheimer, Melanie: Oceans of love. Narrelle, an Australian nurse in World War I, Sydney 2006: ABC Books.

- Oppenheimer, Melanie: Red Cross VADs. A history of the VAD Movement in New South Wales, Sydney 1999: Ohio Productions.

- Rees, Peter: The other Anzacs. Nurses at war, 1914-18, Crows Nest 2008: Allen & Unwin.

- Scates, Bruce: The unknown sock knitter. Voluntary work, emotional labour, bereavement and the Great War, in: Labour History 81, 2001, pp. 29-51.

- Scates, Bruce / Frances, Rae: Women and the Great War, Cambridge; New York 1997: Cambridge University Press.

- Stubbings, Leon: 'Look what you started Henry!' A history of the Australian Red Cross 1914-1991, East Melbourne 1992: Australian Red Cross Society.