The First World War↑

The Western Front was a place where life and landscape were consumed by the technical and industrial prowess of 20th century warfare. The surface was reserved for the dead, while the living stayed underground. No man’s land was an artificial world without colour or life, scarred with trench lines, shell holes and enormous mine craters. Trees were reduced to rotten stumps, yet even these could be artificial – metal replicas designed to disguise forward observation posts or house machine guns. Here, the red corn poppy flowered, bringing bright red hues to fields of dull grey and brown. To many, it symbolised the human experience of the war.

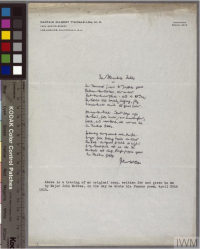

The flower’s seeming ubiquity on the battlefields was clear to John McCrae (1872-1918), who on 2 May 1915, at Essex Farm near Ypres, used the plant as the basis for a hurriedly written poem that would cement the poppy as a symbol of loss. A Canadian doctor, McCrae understood the pain-relieving properties of the poppy. That day, his best friend, Alexis Helmer (1892-1915) had died. Inspired by the sight of red poppies growing between the fresh graves outside his dressing station, McCrae wrote In Flanders Fields: “In Flanders fields the poppies blow / Between the crosses, row on row.”[1]

From Flower to Symbol of Remembrance↑

More than three years later, an American woman, Moina Belle Michael (1869-1944), read McCrae’s words in New York. Michael was desperate to be involved in the war, and the Canadian’s poem inspired her. She wrote her own response to his final stanza, and then went out to buy red corn poppies. None were available, so instead she bought silk ones. This was the genesis of the remembrance poppy, and Michael spent the rest of her life perfecting the idea. Others, too, had seen the potential of the poppy, not least a French woman, Anna Guérin (1878-1961). While Michael had been garnering support for her symbol in the United States, Guérin had been producing her own artificial poppies in Paris. It was this two-pronged, yet disparate approach that was to establish the poppy as Britain’s official symbol of remembrance. Guérin was friends with Douglas Haig (1861-1928) and it was he who first brought the poppy to the attention of the British Legion, which promptly used the symbol for their appeal fund in 1921. Nine million were ordered that first year. Silk proved too expensive to meet demand, so paper was used instead, and they were produced in their millions by the war-wounded. The money raised went to the injured and bereaved, and in 1922 over thirty million were ordered from the British Legion factory in Richmond.[2] McCrae, Haig, Guérin, and Michael had all contributed to the birth of the remembrance poppy, and as it flowered on the shattered battlefields of France and Belgium, it also took root in the hearts of the public. That something so beautiful and hardy could blossom from such destruction was the perfect metaphor for a shattered world desperate to live again.

The Remembrance Poppy Today↑

Different styles and colours of poppy have currency in various contexts. The Scottish version has twice the number of leaves, while France prefers the blue cornflower, or Le bleuet. Its colour matching the poilu’s uniform, thus resonating with the French public who had lost so many of their own. In Belgium, the poppy rapidly replaced the more traditional daisy, which had never really taken hold in the country’s psyche. In America, a red, white, and blue ribbon was used. White poppies are worn with or instead of red ones, signalling a desire for peace. Black poppies bring attention to world hunger, and purple ones commemorate the animals that suffered and died in conflict.[3] There is no official flower of remembrance in Germany.

The poppy is particularly central to the way Britain remembers. In the days leading up to 11 November each year the poppy becomes fleetingly ubiquitous as it flowers on the lapels of the public. On Remembrance Day schools and colleges across the country hold memorial services in front of poppy wreaths, sites of memory in France and Belgium are visited by thousands of British pilgrims – most of whom bring the little red flower with them, or buy one from the many visitor centres and tourism shops. Television programmes adopt poppies in the credits, and families see the lives of their forebears reflected in the red paper petals.

With such notoriety comes inevitable controversy. British politicians refuse to be seen without a poppy, and celebrities help the Royal British Legion to promote the flower. Those who choose not to wear one are either commended for their “bravery” or ridiculed for their lack of empathy. The small red flower has become a contested object of conflict.[4] Nevertheless, it is still worn by many every year, and will be for many years to come.

Matthew Leonard, University of Bristol

Section Editor: Jennifer Wellington

Notes

- ↑ In Flanders fields the poppies blow / Between the crosses, row on row, / That mark our place; and in the sky / The larks, still bravely singing, fly / Scarce heard amid the guns below. / We are the Dead. Short days ago / We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow, / Loved and were loved, and now we lie / In Flanders fields. / Take up our quarrel with the foe: / To you from failing hands we throw / The torch; be yours to hold it high. / If ye break faith with us who die / We shall not sleep, though poppies grow / In Flanders fields.

- ↑ Leonard, Matt: Poppyganda, Eastbourne 2015, p. 59.

- ↑ Ibid, p. 68.

- ↑ Saunders, Nicholas J.: The Poppy. A Cultural History from Ancient Egypt to Flanders Fields and Afghanistan, London 2013.

Selected Bibliography

- Leonard, Matthew: Poppyganda: the historical and social impact of a flower, London 2015: Uniform Press.

- Michael, Moina Belle / Roan, Leonard: The miracle flower: the story of the Flanders Fields memorial poppy, Philadelphia 1941: Dorrance and Company.

- Saunders, Nicholas J.: The poppy. A cultural history from ancient Egypt to Flanders Fields to Afghanistan, London 2013: Oneworld.

- Saunders, Nicholas J.: Material culture and conflict. The Great War, 1914-2003, in: Saunders, Nicholas J. (ed.): Matters of conflict. Material culture, memory and the First World War, London 2004: Routledge, pp. 5-25.

- Winter, Jay: Sites of memory, sites of mourning. The Great War in European cultural history, Cambridge 2000: Cambridge University Press.