Introduction↑

When war broke out on 5 August 1914, New Zealand’s Reform Government under William Massey (1856-1925), and the overwhelming majority of its populace, were unwavering in their support for Great Britain. The great majority of New Zealanders possessed a keen sense of imperialistic duty to what was commonly referred to as the “mother country” in her perceived time of need. The subsequent jingoism knew no bounds. On 6 August, the country’s largest newspaper expressed its enthusiasm in romantic terms. “War,” it extolled. “There is no conception more inspiring, no condition nobler, no call that rings more gladly in the ears.”[1] When New Zealand first entered the war, this unabashed enthusiasm was tempered only by some anxiety as to what lay ahead.[2] Young men of military age rushed to enlist; local body politicians established patriotic funds that, in many cases, became fully subscribed; patriotic groups were established, many by women who would have sons or husbands at the frontline; fetes, carnivals and concerts raised funds for patriotic causes. More antagonistic elements in society formed anti-German leagues and white feather societies.

Pacifist Opposition↑

The energy and strength of the patriotic cause contrasted strongly with the insularity of the few who defied the jingoism that accompanied the war’s outbreak. In this atmosphere, the pacifist response was desultory. Two peace groups existed in August 1914: In June 1911, Baptist lay preacher Charles Mackie (1869-1943) had founded a National Peace Council, an umbrella organisation comprising delegates from church, community, and peace groups.[3] Before the war, it pursued an anti-war propaganda campaign through pamphlets, letters, public meetings, and rallies in Christchurch’s Cathedral Square, where it was based.

In Auckland, in June 1913, the Quaker Egerton Gill (1877-1937) had started a more expansive pacifist group, the New Zealand Freedom League. At the outbreak of war, the League had six branches and some 500 members, mostly Christians. Gill, fellow Quaker Ernest Wright, and the organisation’s first chairman, Reverend Richard Hall, wrote court reports for compulsory military training dissenters (introduced into New Zealand in 1911), distributed anti-war leaflets and pamphlets, and wrote "peace" letters to newspaper editors, civic leaders, and national politicians.[4] The street rallies and public meetings organised by the Peace Council and Freedom League were the highpoint of pacifist activism up until August 1914. Then everything changed. The atmosphere became inhospitable as these people felt the sharp bite of public opprobrium.

On 2 November 1914, Parliament passed a War Regulations Act, umbrella legislation for the web of rules and regulations concerning wartime matters, including the suppression of “seditious” activity. The act stated that any activity deemed to be “injurious to the public safety, called sedition, would be liable on summary conviction before a magistrate to imprisonment to a term not exceeding 12 months, or to a fine not exceeding £100.”[5]

The sanctions would be interpreted very broadly, such that any public critics of the war, or the government’s pursuit of it – expressed either vocally or in written form – could now be deemed to be guilty of a criminal offence. Pacifists retreated to quiet, behind-doors meetings among a diminishing number of members. Mackie refused to compose and distribute pamphlets under the Peace Council banner, instead forming an alliance with the pacifist Union of Democratic Control in London and surreptitiously distributing their propaganda, as well as other overseas material. In November 1915, the police confiscated a box of 500 leaflets from the British Stop the War Committee addressed to Mackie.[6]

Gill was one of very few pacifists who kept his head above the parapet. On 21 October, police raided the Auckland offices of the Freedom League and seized the organisation’s minute books and correspondence. It also arrested Gill for “distributing a prohibited document” vis-à-vis an altered Registration Card for a 1915 National Registration Bill. He was fined £50. Later, in February 1918, he was fined £80 when he was caught in public in possession of a British Fellowship of Reconciliation pamphlet.[7] Gill was now firmly affixed on the state’s radar as an undesirable malcontent. On 3 May 1918, at the age of forty-one, he was balloted for military service. He protested on conscience grounds, but was deemed "insincere" and sentenced to nine months’ imprisonment.[8]

Gill was among a very small number of pacifists who remained active during this war. James Chapple (1865-1947), a Unitarian minister in Timaru who preached against the war, was forced to leave with his family for the United States in December 1915 to escape the hostility, vowing not to return until “democracy crushes militarism”.[9]

The pacifist voice was slight, sporadic, and often individualistic, and posed no threat to the state. Other opponents of the war were in doubt as to where they stood in the unforgiving atmosphere. Christchurch anti-militarist and prominent trade-union leader Jack McCullough (1860-1947) had spoken at Peace Council rallies before the war, but was intimidated by the xenophobia that accompanied the war’s outbreak. After the war, he stated that he had been “afraid” to express his views in public because of their unpopularity and that he was in a “helpless and hopeless minority.”[10] In July 1915, when a Presbyterian minister tried to move a pacifist remit at a meeting of the Christchurch Presbytery, he failed to attract a seconder. “It was a very hostile meeting,” he told Charles Mackie, “and I feel deeply grieved.”[11]

In late 1915, when anti-militarist Thomas Brocas (1869-1932) wrote a letter to the paper stating that all armies committed atrocities, he was so hounded by the local “rabid, militaristic and jingoistic” crowd that he took temporary refuge in Tasmania, “in a state,” he wrote, “of mental torment”.[12] In September of the same year, Christchurch Quaker Sarah Saunders Page (1863-1950), who would prove to be the staunchest of a very small number of female pacifists, confessed to Mackie a “feeling of hopelessness” in advancing her message.[13] When Auckland Methodist minister Reverend Percy Paris (1882-1942) attempted to establish a New Zealand branch of the International Fellowship of Reconciliation, an international Christian movement, it soon disbanded due to lack of support.[14]

Opposition to Military Conscription↑

While few women pursued the pacifist cause during the war, the period did see the emergence of a New Zealand branch of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, established by Marianne Jones and Annette D’Arcy Hamilton in Auckland; others soon followed in Wellington and Christchurch. While their main activity was to keep in touch with their counterparts in Great Britain, Europe, and the United States, they did bring young socialist Adela Pankhurst (1885-1961) – daughter of British suffragist Emmeline Pankhurst (1858-1928) – to New Zealand to give a series of “peace” lectures in May and June of 1916. 2,000 people crowded into the Auckland Town Hall to hear her on 25 May.[15]

Many of Pankhurst’s lectures were based on the need for New Zealanders to fight the forthcoming introduction of military conscription, and opposition to this development later that year and into 1917 is the most potent story of dissent during the war. A handful of Christian pacifists spoke out against conscription. When the US did enter the war, James Chapple returned to Christchurch, where he gave lectures criticising the war, conscription, and profiteering. After increasing hostility caused these lectures to be cancelled, he travelled to the trade-union stronghold of Greymouth on 6 March 1918, but was arrested for sedition after he gave a speech stating that patriotism and militarism were “poisoning” New Zealand and sentenced to eleven months’ imprisonment.[16] Another Christian pacifist, Harry Urquhart (1879-1963), was arrested after giving a public lecture on 28 January 1917, where he condemned conscription as unchristian.[17] Police deemed the speech seditious, and on trial, the magistrate, accusing him of having an “unbalanced mind”, sent Urquhart to jail for eleven months. On release, like Gill, he was also conscripted, appealed on conscience grounds, judged “insincere”, and sentenced to a further eleven months as a military defaulter.[18]

Decisions supporting or opposing military conscription were inextricably tied to Labour politics. Moderate labourites, the inheritors of the liberal-labour tradition of consensus, pragmatism, and arbitrationist politics, generally supported the war when it broke out. Not so the militants who objected, on class grounds, that the war was simply another way in which capitalists exploited workers for undeserved profit. Their case was based on the untrammelled profiteering that went on under the guise of production for the war effort as the war proceeded. Food prices, for example, rose 25 percent over the course of the war, whereas wages rose less than 15 percent.[19]

Labourite opposition to military conscription was linked to the unfair and growing disparities in distribution of wealth and profit among New Zealanders. Labourites believed that the conscription of men should either be preceded or accompanied by a conscription of wealth. In pragmatic terms, this meant confiscating enough wealth to raise military pay and pensions to acceptable levels.

There was little doubt by late 1915 that conscription would be introduced as the number of voluntary recruits for the armed services dwindled. The government’s National Registration Bill of 25 August 1915 brought the debate into sharp focus. The "war census" revealed that just 58 percent of respondents were prepared to join the expeditionary force overseas, prompting the government to introduce conscription in a Military Service Bill on 24 May 1916, becoming law as The Military Service Act on 1 August. On 4 December 1916, the government gazetted further, equally tough regulations against critics of conscription. They declared seditious “any incitement of class ill-will, any interference with recruiting or war production, any discouragement of the prosecution of the war, or any encouragement of opposition to conscription”.[20]

The primary overt opposition to conscription came from the labour movement in general and the burgeoning Labour Party in particular. Anti-conscription leagues were established around the country in early 1916.[21] Anti-conscriptionist Bob Semple (1873-1955) was a leader, charismatic and persuasive. Judicial antagonism towards him was rife. After he addressed a sold-out, and enthusiastic, anti-conscription meeting in Auckland’s Globe early in December 1916, Solicitor-General John William Salmond (1862-1924) described him as “one of the most dangerous and mischievous men in New Zealand”.[22] Salmond’s annoyance was manifest. Before Semple’s trial, he told the Crown Solicitor that his job was to obtain “as long as term of imprisonment as is practicable; there should be no question of a mere fine”. The government believed that his incarceration, along with that of other “socialist rabble-rousers”, would end all public opposition to conscription.[23]

Within weeks, socialist Labour agitators James Thorn (1882-1956), Fred Cooke (1867-1930), Peter Fraser (1884-1950), Tim Armstrong (1875-1942), and Tom Brindle (1878-1950) had been arrested, tried, and found guilty by magistrate only – being denied a trial by jury under the emergency regulations – and, like Semple, imprisoned for twelve months.[24] By the end of December, almost half of Labour’s most effective platform speakers had been incarcerated for sedition.[25]

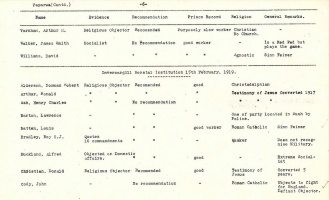

Conscientious Exemption↑

Even mild criticism of conscription could result in prison sentences. By the end of the war, there had been 102 successful prosecutions for sedition; sixty-seven people had been imprisoned, twenty-nine had been fined, and eight convicted and discharged. Among those incarcerated were seventy-year-old Ellen Fuller, who was overheard making “seditious” remarks at the Palmerston North railway station, and Toiwhare, a Waikato Māori who stated that he “would like to see the Germans win and come to New Zealand”.[26]

Christian pacifists, both those who belonged to churches and sects, who in some cases were encouraged, or told, by their church leaders to resist military service, and those acting as individuals, also opposed conscription. They believed that bearing arms was contrary to the will of God and that forcing young men into uniform would undermine parental and biblical authority and promote violence.[27]

The Defence Department under Allen ensured that the religious exemption was kept very narrow to stop what it called the unscrupulous use of religion to avoid military service. Only members of the Society of Friends and a very small American sect, the Christadelphians, were granted automatic exemption because their constitutions included pacifist tenets. Communicant members of mainstream churches and all of those with religious scruples who considered themselves absolute pacifists were not excused from military service.

Apart from those resisting conscription on religious or political grounds, three other categories of objectors emerged during the war. There were a small number of Irish immigrants, Sinn Feiners, some of whose Catholic kin in Ireland were in vigorous rebellion against the British colonial yoke. There were Māori objectors, principally from the Tainui iwi in the Waikato, who saw the conflict as not theirs, but British. They were only one generation away from those lands had been confiscated after the 1860s land wars. The third category encompassed individuals who belonged to no organisation and pronounced no specific belief except a strong ethical objection to fighting in war and being conscripted to do so.[28]

By the end of the war, the New Zealand government had called up 138,034 men for military service under conscription. Every man could appeal his call-up through his local Military Service Board, which was empowered to exempt men if they worked in an essential industry, if their enlistment would cause “undue hardship” to their family, or if they were members of a pacifist religious group.[29]

During the war, the boards heard 43,544 appeals and offered provisional exemptions to 11,343 men on the grounds of essential industry or undue hardship. Only sixty men were granted exemptions on religious grounds; another thirteen rejected exemptions they were offered. By the end of the war, 32,270 conscripts had been sent to camp to serve in the New Zealand Expeditionary Force, of whom 19,548 had embarked for the frontline. Conversely, 286 conscientious objectors whose appeals were rejected, and thereafter refused to serve, were imprisoned, most for two years’ hard labour.[30] Initially, they were incarcerated in military camps before being sent to prison. Their families received no income and were left to fend for themselves.

On 6 December 1918, Parliament passed an Expeditionary Forces Amendment Act depriving imprisoned objectors, deserters, and men who failed to appear when called upon of their civil rights, including their right to vote, for ten years.[31] Allen, with a "defaulters" list published in May 1919, disenfranchised some 2,320 defaulters, after the names of ninety-nine men had been deleted on appeal. The Act also debarred them from employment in the government – including as schoolteachers – or by a local body.[32] Meetings of over 2,000 people in each of the four main centres unsuccessfully demanded the restoration of civil rights to those affected.[33] All the defaulters had their rights restored in September 1927, a year earlier than the legislation had originally allowed.[34]

The Fourteen↑

In mid-1917, the Defence Department reviewed the objectors then incarcerated and decided that those who still rejected any form of military service would be sent overseas on the next troopship. Thus, in July, fourteen men were chosen by the district military authorities to be made examples of. The group was composed of labouring and industrial workers because it was believed that there be less visible protest from working-class families. The chosen included three brothers: Alexander "Sandy" Baxter (1880-?), Archibald Baxter (1881-1970), and John Baxter (1891-?) of Brighton, Otago.[35]

The men left New Zealand aboard the troopship Waitemata on 14 July 1917, imprisoned in the ship’s lock-up. They were stripped and forced into military uniform. Imprisoned at Sling Camp in Wiltshire under bleak conditions, three of the men were forced by hunger and illness to change their minds. (A fourth was sent back to New Zealand when he was belatedly acknowledged as a "genuine" religious objector under the Act.) The remaining ten were despatched to France in late 1917 and early 1918. Subject to more bullying, four more were persuaded to don uniform and become non-combatant stretcher bearers. Three of the remaining six were sentenced to imprisonment, to be served in the exceptionally brutal military prison at Dunkirk. All subsequently agreed to become stretcher bearers. One, William Little (1895-1918), was killed in action.

The last four objectors, Henry Patton (1878-?), Lawrence Kirwan (1891-?), Mark Briggs (1884-1965), and Archibald Baxter were all sentenced to Field Punishment No. 1, which involved tying a man to a sloping pole in a hanging position with their feet off the ground which cut off circulation to the hands, causing extreme pain. Patton then agreed to become a stretcher bearer; the other three were ordered into frontline trenches. Briggs refused to walk up to the fontlines, so was dragged over rough ground and shell-holes before being thrown in a shell hole. He was severely injured, hospitalised, diagnosed with rheumatism, declared medically unfit, and finally discharged. Kirwan agreed to be a stretcher bearer.

Archibald Baxter, the sole remaining objector, was slowly starved and sent into dangerous areas in the apparent hope he would be killed. He wandered away from his unit, became delirious, collapsed from the effects of starvation, and after a particularly brutal beating from a military policeman, was hospitalised. Military doctors in England diagnosed him as insane, a diagnosis he later contested. A few months later, he was returned to New Zealand as medically unfit.

Allen and at least some of his officers dealing with the fourteen men realised that public perception of the episode would need to be carefully managed. They wanted the men to be regarded as unpatriotic shirkers being justly forced to “do their bit” by a fair-minded state, rather than sensitive men of principle being brutalised and tortured by punitive officials. In this regard, Allen was disappointed. News of the fourteen’s deportation had already been leaked to family members and the press after the Waitemata’s departure, including stories of the men’s mistreatment aboard. The furore grew when rumours of the brutal treatment of these men reached New Zealand in the autumn of 1918.

Anti-militarists and civil libertarians attacked the callousness of Allen and his department, accusing them of indulging in the sort of draconian “un-British” practices of which the Germans were guilty, and which the war, in part, was intended to abolish. Allen never conceded that his department had made a mistake in deporting the men, but, as his critics pointed out, the experiment was not repeated.

Conclusion↑

Most of the imprisoned objectors were still behind bars at the time of the Armistice in November 1918, some serving a second or even third consecutive sentence for refusing military service. Labour and anti-militarist groups began campaigning for the objectors’ release. Returned servicemen’s associations were staunchly opposed to any leniency for objectors.

Allen remained firm in his resolve to punish those who had refused to serve. He believed that the country’s real debt was to its servicemen, who should be given the opportunity to return home and establish themselves before dissenters were given the same privilege. He did have some sympathy for men who presented a religious objection to war, as long as he felt it was genuine, but this sympathy was belated. In early 1919, he created a Religious Advisory Board to identify "genuine" religious cases, and afterwards remitted some sentences on the Board’s recommendations. This was after the war had already ended, however. Conversely, the rest of the incarcerated men – including another 113 sentenced after the Armistice for defaulting or deserting – remained in prison, serving out their sentences. The last of the imprisoned objectors was released from jail in August 1920; three months later, an amnesty was declared on all defaulters still at large.[36]

David Grant, Independent Scholar

Section Editor: Kate Hunter

Notes

- ↑ New Zealand Herald, 8 August 1914, p. 1.

- ↑ See Hucker, Graham: The Great Wave of Enthusiasm. New Zealand Reactions to the First World War in August 1914. A Reassessment, in: New Zealand Journal of History 43/1 (April 2009), pp. 12-27.

- ↑ Cookson, J. E.: Mackie, Charles Robert Norris, in: Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, issued by: Te Ara. The Online Encyclopedia of New Zealand, online: www.teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/3m20/mackie-charles-robert-norris (retrieved: 11 June 2018).

- ↑ This information is gleaned from the Freedom League’s Minute Books between March 1913 and July 1914. See Alexander Turnbull Library (ATL), MS-Papers-2531-1, ‘New Zealand Freedom League: Minute Books’ and MS-Papers-2531-2, ‘New Zealand Freedom League: Minute Books’. See also Brailsford, John A.: Obituary of Egerton Gill, A Champion of Peace and Freedom, in: Tomorrow, 2 February 1938, p. 8.

- ↑ New Zealand Gazette, 10 November 1914, pp. 4021-4024, War Regulations Act, pp. 22-26. Baker, Paul: King and Country Call. New Zealanders, Conscription and the Great War, Auckland 1998, p. 75.

- ↑ Grant, David: Where were the Peacemongers? Pacifists in New Zealand during World War One, in: Loveridge, Steven (ed.): New Zealand Society at War 1914-1918, Wellington 2016, p. 227.

- ↑ ATL, MS-Papers-2597-29/02, ‘New Zealand Yearly Meeting of the Society of Friends’, Eric J. Appleby to Friends, 31 January 1918.

- ↑ This was despite the magistrate’s comments that he was reluctant to convict Gill, as he believed that there was no doubt as to his honesty of purpose. As a measure of the magistrate’s respect, Gill was permitted a light in his cells so that he could study until 9pm. ATL, MS-Papers-29/02, ‘New Zealand Yearly Meeting of the Society of Friends’, Alfred M. Naughton to Friends, 7 September 1918.

- ↑ Maoriland Worker (MW), 8 December 1915, p. 6.

- ↑ Nolan, Melanie: McCullough, John Alexander, in: Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, issued by: Te Ara. The Online Encyclopedia of New Zealand, online: [1] (retrieved: 11 June 2018).

- ↑ Quoted in Baker, Paul: New Zealanders, Conscription and the Great War (thesis, University of Auckland), Auckland 1986, p. 152.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 153.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 152. Hutching, Megan: Turn back this Tide of Barbarism. New Zealand Women who were Opposed to War, 1896-1919 (thesis, University of Auckland), Auckland 1990.

- ↑ Quoted in Grant, David: Out In the Cold. Pacifists and Conscientious Objectors During World War 2, Auckland 1986, p. 33.

- ↑ Truth, 28 July, p. 8

- ↑ Chapple, Geoff: Chapple, James Henry George, in: Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, issued by: Te Ara. The Online Encyclopedia of New Zealand, online: [2] (retrieved: 11 June 2018). Baker, King and Country Call 1998, p. 76.

- ↑ His address was later published as a booklet: Urquhart, Harry: Men and Marbles, Auckland 1917.

- ↑ Grant, Where were the Peacemongers? 2016, p. 232.

- ↑ Quoted in Webb, Paddy: New Zealand Parliamentary Debates (NZPD) 172, p. 554.

- ↑ New Zealand Gazette Extraordinary III/136, 4 December 1916, pp. 3751-3753.

- ↑ Baker, King and Country Call 1998, pp. 44, 69.

- ↑ Semple later implored West Coast miners "not to be by the Prussian octopus of conscription… [I]t is aimed not at the Kaiser but the working classes". New Zealand Herald, 16 December 1916, p. 6.

- ↑ Grant, David: Peter Fraser. Anti-Conscription, Conscription and the Referendum, in: Clark, Margaret (ed.): Peter Fraser. Master Politician, Palmerston North 1998, p. 132.

- ↑ New Zealand Gazette Extraordinary III/136, December 1916, pp. 3751-3753. Fraser would go on to become Prime Minister of New Zealand in 1940.

- ↑ Holland, H. H.: Armageddon or Calvary, Wellington 1919, p. 14.

- ↑ Quoted in Shoebridge, Tim: New Zealanders who resisted the First World War, in: NZHistory. New Zealand History Online, issued by: The Ministry of Culture and Heritage, online: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/first-world-war/sedition-conviction-list (retrieved: 5 February 2018).

- ↑ Quoted in Shoebridge, Tim: Conscientious Objection and Dissent, in: NZHistory. New Zealand History Online, issued by: The Ministry of Culture and Heritage, online: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/war/first-world-war/conscientious-objection (retrieved: 22 December 2017).

- ↑ Grant, David: Field Punishment No. 1. Archibald Baxter, Mark Briggs and New Zealand’s Anti-Militarist Tradition, Wellington 2008, pp. 37-38.

- ↑ Shoebridge, Conscientious Objection and Dissent.

- ↑ Ibid. Of these 286, 141 identified themselves as religious objectors, fifty-nine as socialists, eleven as religious/socialist, twenty-three as Irish, twenty as unspecified non-religious, three as philosophical pacifist, fourteen as Waikato Māori, three as not a reservist, and six not recorded.

- ↑ Dominion, 24 November 1919.

- ↑ Maoriland Worker, 16 July 1919.

- ↑ Quoted in Gustafson, Barry: Labour’s Path to Political Independence. The Origins and Establishment of the New Zealand Labour Party 1900-19, Auckland 1980, p. 116.

- ↑ Labour MP Paddy Webb was one of these. After his release from prison as a military defaulter in 1918, he was barred from returning to parliament for ten years. He became a coal merchant.

- ↑ Information in the following eight paragraphs is gleaned from Grant, Field Punishment No. 1 2008, pp. 39-115 passim; Baxter, Archibald: We Will Not Cease. The Autobiography of a Conscientious Objector, Christchurch 1968; Shoebridge, Conscientious Objection and Dissent. Written after a revisit to the Salisbury Plain during a tour of Britain in 1938, Baxter’s We Will Not Cease has become an iconic work in the annals of New Zealand literature.

- ↑ Shoebridge, Conscientious Objection and Dissent.

Selected Bibliography

- Baker, Paul: King and country call. New Zealanders, conscription, and the Great War, Auckland 1988: Auckland University Press.

- Baxter, Archibald: We will not cease. the autobiography of a conscientious objector, Christchurch 1968: Caxton Press.

- New Zealand Gazette Extraordinary, III, June 1916, p. 796. Archives New Zealand, Wellington: New Zealand Gazette Extraordinary, III, June 1916, p. 796. Archives New Zealand, Wellington, 3333, 3333.

- New Zealanders, conscription and the Great War, thesis (in English): New Zealanders, conscription and the Great War, thesis, Auckland 1986: University of Auckland, 1986.

- Freedom League Minute Books, March 1913-July 1914. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington.

- Grant, David: Field punishment no. 1. Archibald Baxter, Mark Briggs & New Zealand's anti-militarist tradition, Wellington 2008: Steele Roberts.

- Grant, David: Out in the cold. Pacifists and conscientious objectors in New Zealand during World War II, Auckland 1986: Reed Methuen.

- Grant, David: Peter Fraser. Anti-conscription, conscription and the referendum, in: Clark, Margaret (ed.): Peter Fraser. Master politician, Palmerston North 1998: Dunmore Press, pp. 113-125.

- Grant, David: Where were the peacemongers? Pacifists in New Zealand during World War One, in: Loveridge, Steven (ed.): New Zealand society at war 1914-1918, Wellington 2016: Victoria University Press, pp. 220-234.

- Gustafson, Barry: Labour's path to political independence. The origins and establishment of the New Zealand Labour Party, 1900-19, Auckland; Wellington 1980: Auckland University Press; Oxford University Press.

- Holland, Henry Edmund: Armageddon or calvary. The conscientious objectors of New Zealand and the process of their conversion, Wellington 1919: The Maoriland Worker Printing and Publishing Co..

- Hucker, Graham: 'The great wave of enthusiasm.' New Zealand reactions to the First World War in August 1914 - A reassessment, in: The New Zealand Journal of History 43/1, 2009, pp. 59-75.

- James Allen Papers, AP D1/53, Archives New Zealand, Wellington.

- Littlewood, David: Military service tribunals and boards in the Great War. Determining the fate of Britain's and New Zealand's conscripts, London; New York 2018: Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group.

- Littlewood, David: Striking a balance. The military service boards, in: Loveridge, Steven (ed.): New Zealand society at war 1914-1918, Wellington 2016: Victoria University Press, pp. 112-126.

- Loveridge, Steven: Calls to arms. New Zealand society and commitment to the Great War, Wellington 2014: Victoria University Press.

- New Zealand Gazette, 10 November 1914, Archives New Zealand, Wellington

- New Zealand parliamentary debates, 172, p. 554; 175, p. 786. Archives New Zealand, Wellington.

- New Zealand yearly meeting of the Society of Friends. Minutes, January, September 1918. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington.