Introduction↑

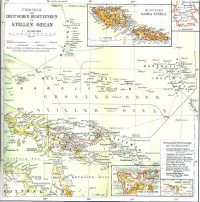

As a member of the British Empire, New Zealand was committed to a war against Germany with Britain’s declaration on 4 August 1914. A small contingent of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF) was despatched almost immediately to the German colony of Samoa, and a force of 7,000-8,000 troops was promised to the British government. Over the course of the war just over 100,000 soldiers served overseas, along with thousands of New Zealand volunteer and paid workers in Britain and Europe. At home, 19,000 kilometres from the main theatres of battle, civilians committed themselves to the financial and material support of soldiers and nurses, and their dependants. Through four and a half years of war, New Zealanders endured war weariness, anxiety and bereavement. Just as they enjoyed the sense of relief brought by the Armistice, however, the influenza pandemic swept through the country, killing 8,600 people, compounding the 16,700 overseas deaths the community had already suffered.

New Zealand in 1914↑

In 1914, New Zealand was a British dominion populated largely by immigrants of British descent and their offspring. The indigenous Maori population had, by the turn of the century, been “subdued” and in the face of massive land loss, introduced diseases, and poverty, had declined significantly in numbers and power. The country’s total population of just over 1 million was dispersed throughout the two large islands, with the four main cities – Auckland, Wellington, Christchurch and Dunedin – containing just under one third of the non-Maori population. A further one in ten residents lived in towns with more than 8,000 people, with the remaining 60 percent of the population living in rural areas. Broadly speaking, Pakeha (non-Maori) and Maori New Zealanders were farmers and artisans.[1]

Politically, New Zealand was progressive: in addition to universal manhood suffrage, white women and all Maori had been enfranchized by the early 1890s; and compulsory, state-funded education had been introduced from the 1880s. While only approximately 15 percent of pupils continued their schooling beyond the age of fourteen, by the time war broke out, New Zealand’s population was broadly enfranchized and reasonably literate.[2] Like other colonies, however, early 20th-century concerns about defence had led to the institution of compulsory military training for boys from the age of fourteen. Ushered in with the Defence Act 1909, the initial requirement that boys as young as twelve participate was tempered by both Department of Education concerns and those of Lord Baden Powell (1857-1941) who visited New Zealand in 1912.

The Great War was not New Zealand’s first. Like many British colonies, the first wars were those fought against indigenous people. New Zealand became a British colony in 1840. The signing of the Treaty of Waitangi between the crown and various – but not all – Maori leaders granted the British sovereignty and was designed to protect Maori interests, although the extent to which this was intended and was practiced has been a bone of contention ever since. The influx of colonists in the following decade led to increasing pressures on land and inevitably to conflict over it. While not the sole cause, land was a main factor in the eruption of conflict between the British and various Maori groups from the 1860s until the 1870s. These “Land Wars”, or “New Zealand Wars” as they later came to be known, had far-reaching consequences for many Maori groups – those who were deemed by the government to have been “rebels” faced land confiscations (raupatu) and subsequent impoverishment and cultural dispossession. Significantly for race relations during the Great War, major confiscations occurred in the upper North Island in the mid-1860s; Maori iwi (tribes) in the Waikato region south of Auckland were swindled out of their lands in the wake of their defeat. Speculators saw the opportunity to develop an agricultural hinterland to support the city, and unscrupulously exploited the confiscations and Waikato iwi disarray.[3] It was from these tribes that significant resistance to war was demonstrated during 1914-1918 (see section on Opposition from Maori).

Mobilizing↑

Britain’s declaration of war was New Zealand’s declaration of war. The governor, Arthur Foljambe, Earl of Liverpool (1870-1941), publicly announced the decision on the steps of Wellington’s parliament house on 5 August. The prime minister’s commitment of an army was published in the morning newspapers, and the enormous logistical work began of raising a volunteer force in a country with no standing army to speak of.

This is not to say that New Zealand had no military force. In the wake of the South African War (1899-1902), to which New Zealand had sent 6,500 volunteers, the government introduced new defence legislation. Hence, the tiny number of regular soldiers in 1914 was complemented by the Territorial Force – reservists trained from the age of fourteen as cadets under the compulsory military training scheme introduced in 1909 (also introduced in Australia). In the first weeks of war, 14,000 men volunteered for service, 8,000 of whom went into camp to embark as the Main Body in October. They were followed by forty-two reinforcements, each of around 2,000 men, over the course of the war. A force was also dispatched to seize and occupy the German colony of Samoa at the end of August 1914, taking with it seven members of the Army Nursing Reserve (the forerunner of the Army Nursing Service) to staff the hospital at Apia. All were subsequently to join the New Zealand Army Nursing Service when it was sanctioned in January 1915, and they served in all theatres of war where New Zealand soldiers were engaged.

As with other dominion armies, a significant proportion of the NZEF – 30 percent – was British-born, and very large numbers were first-generation New Zealanders with relatives in Britain. When William Dawbin (1888-1915), a young farmer from a rural area in the lower North Island, was wounded in France and evacuated to Netley Hospital in Southampton, his cousin lived close enough to visit him and provide extra nursing care, which she did despite the fact they had never before met. When William died in August 1915, his mother’s family claimed his body, buried him in the family plot in Somerset and sent his New Zealand family a photo of the grave.

The government took some months to accept the offers of service from nurses. Matron-in-Chief of the Army Nursing Reserve Hester Maclean (1859-1932) offered nurses for overseas service immediately war was declared, but the formation of the New Zealand Army Nursing Service (NZANS) was not achieved until January 1915. The first group of nurses departed for Egypt in April, with a more substantial number embarking for the Dardanelles on the Hospital Ship Maheno in June. As with other nursing services, the NZANS served alongside the military, not as part of it. In many ways they bridged the spaces, the conditions of soldiers and the support services such as YMCA and Red Cross workers.

New Zealand nurses were the focus of the second great shock to New Zealanders of 1915. Reporting of the landing at the Dardanelles on 25 April had both made New Zealand and Australian soldiers visible to the empire, and created the first major casualty lists of the Great War in New Zealand’s newspapers. After months of enduring the Gallipoli stalemate, news reached New Zealand of the sinking of the troop transport Marquette in the Aegean Sea on 23 October, a terrifying ordeal that resulted in the deaths of ten NZANS nurses and another nineteen male staff of NZ No.1 General Hospital.

Volunteerism fulfilled the NZEF’s needs until late 1915, when numbers began to drop off. New Zealand men were the target of the enormous propaganda campaign waged by the British government, as well as local and targeted recruitment campaigns. Recruitment posters, rallies and the engagement of women and children as recruiting agents added to the social pressure applied daily to men of military age through patriotic displays, shop windows and what one young man described as “cutting innuendoes, frigid looks and unkind remarks”.[4] Eventually calls for the introduction of conscription led to the passage of the Military Service Bill in August 1916 and the first ballot in November of that year (see section on Conscription). Of the 100,000 men who served in the NZEF, approximately one third was conscripted.[5]

New Zealand’s Campaigns↑

Broadly speaking, the New Zealand forces were deployed initially in the Middle East, including on Gallipoli. By April 1916, the bulk of the NZEF were on the western front, and they finished the war as part of the occupation force in Germany. The NZEF joined the British attack on the Dardanelles in 1915, and the New Zealand Division was deployed in France early in 1916. The New Zealanders participated in the ongoing Somme Offensive in September 1916, and then were part of the two major offensives in Belgium in 1917: Messines and the Third Battle of Ypres/Ieper (Passchendaele). In March 1918, they were involved in halting the German Spring Offensive, and marched into Germany in November 1918. The smaller New Zealand Mounted Rifles fought in Sinai and Palestine until the armistice with the Ottoman Empire in October 1918.

New Zealanders were also spread throughout the other dominion and imperial forces, as well as the Royal Navy and Royal Flying Corps. In particular, medical students who had been in Edinburgh and London when war broke out, served with the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC), and young, ambitious NZEF officers applied for commissions in the British Army. New Zealand nurses served with the New Zealand Army Nursing Service, formed in 1915, as well as with the Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service, the Scottish Women’s Hospital, the British Red Cross and the Australian Army Nursing Service. In this capacity, nurses served in a wide variety of settings from casualty clearing stations to hospital ships, on board troop ships and in general and auxiliary hospitals from Britain to the Middle East.[6]

Conscription↑

By late 1915 government ministers and military authorities were raising the question of military conscription. A flush of volunteers in May and June (in response to the news of early casualties in the Gallipoli campaign) had dried up and government ministers became anxious not only about New Zealand’s ability to fulfil their obligations to Britain, but about the unequal burden volunteerism placed on some sectors of society. Newspaper cartoonists took up this theme with an increasing focus on shaming “the shirker” or “the slacker”. Front page caricatures depicted the slightly built, slouching man, usually with a racing form in his back pocket, as an increasing threat to the war effort.

Despite the introduction of conscription in Britain in February, the less robust New Zealand government held off bringing in compulsion because of the fear of opposition to it.[7] The government was already concerned about industrial unrest (see section on Social and Political Tensions) and continued for some months to rely on a moral campaign that included requests that neighbours send the names of non-enlisted eligible men to the local recruiting committee. The rhetoric of “equality of sacrifice” resonated strongly with many segments of society and it was generally agreed that only conscription could even out what many saw as the burden falling most heavily on those families with a strong sense of duty.

In the face of sustained opposition from socialists, pacifists and unions, a last attempt to avoid introducing conscription, modelled on the British Derby Scheme, was launched in February 1916. Local recruiting committees canvassed local eligible men individually, but while increasing numbers of men were medically examined in these months, enlistment numbers did not jump. By April it was clear that the scheme was not going to work, and the Military Service Bill was introduced in May. The Bill passed on 1 August 1916 and the first ballot was drawn in November. The New Zealand balloting system was “entirely original”.[8] Every reservist’s name was on a card, and 500 cards filled each of 233 numbered drawers. The ballot box – a small hexagonal timber barrel full of numbered marbles – had to be rolled twice: the first number drawn was the number of the draw, the second the man’s card. Ballotted men were gazetted and had one month to appeal.

Appeals were made on many grounds, but the dependence of other family members was the most common, accounting for approximately 40 percent of appeals.[9] A great many eligible men were supporting elderly parents and siblings, and felt that they could not leave. This was especially the case where a man’s enlistment would have resulted in a drop in family income. Farming men were also very reluctant to leave their farms, which they feared would revert to scrub in their absence, or they could not find buyers for their stock or land. The local nature of Military Service Boards meant that such appeals were dealt with in an uneven manner across the country. Police Gazettes from late 1916 onwards also reveal significant numbers of both defaulters (men who did not report for medical examination) and deserters (men who had been examined and enlisted but who did not report to camp) for whom arrest warrants were issued, indicating low level resistance among the community.[10]

Maori Experiences↑

Entangled lives↑

The life of Taranaki-born Maui Wiremu Piti Naera Pomare (1875/6?-1930) illustrates the links between and complexities of New Zealand’s colonial history and Maori participation in the Great War. Maui Pomare’s grandmother, Kahe Te Rau-o-te-rangi (?-1871?), was one of the few women to sign the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840. Forty years later Maui’s mother, Mere Hautonga Nicoll, faced the Armed Constabulary at the sacking of the Taranaki pacifist community Parihaka in 1881 with the five-year old Maui in her arms. A subject of assimilationist policies and a beneficiary of the granting of indigenous political rights, Maui was educated at St Stephen’s Native Boys’ School and then at Christchurch Boys’ High School. When he was orphaned at the age of fourteen, his aunt sent him to the influential Te Aute College where he developed an interest in Maori health and medicine. After studying with a tohunga (traditional healer) and in the United States as a medical missionary he was appointed as a government Maori health officer in 1901. A voluble activist for Maori health, and improvement in living conditions, he eventually entered parliament in 1911 with the support of the Waikato and Taranaki iwi as the MP for Taranaki. Pomare was well educated, well dressed and good humoured. He had also married Mildred Woodbine Johnson (1877-1971) in 1903: she was bilingual, educated and a consummate hostess. Together they became a glittering political couple. Pomare’s first political campaign was an attempt to regain Maori control over Taranaki lands confiscated by the government during the nineteenth century. When war broke out in 1914, Pomare was one of several Maori MPs who saw a chance for Maori to demonstrate their readiness to act as full citizens and their deservedness to be treated as such. He chaired the recruitment committee and, when volunteerism reached its limit among those Maori groups who agreed with enlistment, he supported the enforcement of conscription against those iwi who had refused to enlist at all, most particularly his relatives and political supporters among Waikato.[11] Pomare was not forgiven by the Waikato iwi for his actions, because over 100 Waikato men were imprisoned for defaulting. Pomare’s family and political connections, and the history of Maori struggles with the government, shaped his political career in this complex time.

Maori in the NZEF↑

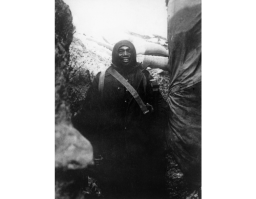

Maori men volunteered for many units of the NZEF but offers of a Maori contingent were initially rejected by the government: the general feeling was that the imperial authorities would not accept non-white troops for the European war, and there were domestic concerns about the demographic effects of enlistment on the already embattled Maori population. When it became known that the Indian Expeditionary Force was to be deployed by the British government, the New Zealand government accepted the arguments by the Maori MPs that a separate unit be established. The first Maori contingent – first formed as the Native Contingent – departed in February 1915. Initially based at Malta on garrison duties, they were sent to Gallipoli in response to mounting casualties and participated in the assault on Sari Bair, sustaining significant casualties.[12] Captain Peter Buck or Te Rangi Hiroa (1877?-1951), who served with the Maori contingent later wrote of the sound of Maori haka (war cry or song) being performed, “and my heart thrilled at the sound of my mother tongue resounding up the slopes of Sari Bair”.[13]

Considerably weakened after the Gallipoli campaign, the Maori contingent was blended with the remnants of the decimated Otago Mounted Rifles into a Pioneer Battalion and spent the rest of the war as a labouring force. Made up of a large number of bush contractors and farm labourers, the Pioneer Battalion were renowned among the Allies for their digging and tree-felling prowess, and their sporting abilities.[14] A further outcome of their war experience was a more general acceptance of Maori by New Zealanders who had previously had little to do with Maori.[15]

Opposition from Maori↑

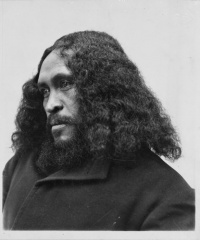

At home in New Zealand, pressure mounted on those iwi (tribal groups) who would not volunteer for service. Some leaders were cautious about Maori participation in the war because of the fragile state of Maori demographic recovery and parliament had deemed Maori exempt from the conscription ballot for this reason. Wholesale opposition to enlistment, however, came from other quarters. The Tuhoe tribal prophet and religious pacifist Rua Kenana (1868?-1937) discouraged voluntary enlistment among his followers, a public stance that eventually saw the government lay charges of sedition against him. Similarly, following the tradition of non-violence established by Waikato leaders in the 1880s, Te Puea Herangi (1883-1952) supported and led Waikato’s refusal to take up arms, especially in support of a power that had unjustly deprived them of their lands. “They tell us to fight for king and country,” she mused. “We’ve got a [Maori] King. But we haven’t got a country. ...Let them give us back our land and then maybe we’ll think about it again.”[16] To quell this protest, which became increasingly embarrassing to the government, a decision was made to enforce the Military Service Act against the men of the Western Maori electorate including Waikato and Ngati Maniopoto iwi. When various attempts to coerce Waikato men to enlist (and fining them for refusing) failed to achieve results, 209 men were formally ballotted: only one third reported to the recruitment office, largely men whose jobs guaranteed them immediate exemption. A major confrontation loomed between police and Waikato. In June 1918 Te Puea assembled about 600 of her people at Mangatawhiri to greet the police who came to arrest the other 141 “defaulters”. Frustrated by her tactics, which included a refusal to identify the men on the list of defaulters, the police provocatively arrested men who were obviously too young or old to be eligible. Waikato would not be goaded, turning their efforts instead to supporting the imprisoned men and their families.

By the end of the war, 552 Maori had been ballotted, seventy-six of whom proved to be ineligible for service. One hundred men had been arrested and eleven sentenced to hard labour. Arrest warrants for another 100 men were processed but unexecuted because of the end of hostilities in Europe. No Maori conscript had been sent overseas; but the emerging idealization of New Zealand’s race relations, boosted by the granting of the vote to Maori in the nineteenth century and their enlistment alongside Pakeha in the NZEF, had been challenged.[17]

War Work↑

Paid work↑

The paid workforce in New Zealand in 1914 was highly stratified: very few occupations involved both men and women, and most workplaces had strict hierarchies of skill and seniority. Children could start work at the age of fourteen, with fewer than one in three pupils staying on at school beyond this age. Women workers dominated textile and clothing factories and domestic service. Men filled most other jobs from unskilled labouring through to skilled manufacturing and professional occupations. At war’s outbreak, small numbers of women had made significant inroads into primary school teaching and a minor incursion into white-collar office work, but only the smallest of dents in the medical profession. As in other British colonies, social and legislative measures had enshrined men as the “breadwinners” in families, guaranteeing them wages upon which they could support a family, while women earned only half of the male wage.

War disrupted these well-established patterns in several ways. First, raising an army required removing male “breadwinners” from their families. In response, the government brought in new welfare measures to provide for dependants of soldiers. The allotment system allowed men to divert part of their military pay to family members, and the government introduced a separation allowance for women and children whose male provider had enlisted.[18] Second, while New Zealand did not have a large munitions industry, the growth in the public service necessary to run a wartime government saw women’s employment in white collar work grow strongly. Most of the 3,000 temporary public service positions created during the war were filled by women. A wholesale change in women’s participation in the paid workforce is not apparent, however, from the censuses during these years, but anecdotally, women did take up a wide range of work to release men for the army. In rural occupations especially, women – often family members rather than paid workers – took on greater workloads. Wartime reminiscences are rich with descriptions of women and children in orchards and hops fields, ploughing, milking, planting and picking.

In early 1917 and after the introduction of conscription (see section on Conscription), the government instituted the National Efficiency Board (NEB) to regulate the wartime economy. The declaration of industries as “essential” or “reserved” was not necessary until the introduction of conscription in August 1916 and the NEB played a major role in these decisions. The conscription–appeals mechanism run at a local level was used by the government to prioritize local economic needs and Military Service Boards were given the power to grant exemptions to men whom they saw as economically vital. However, central government retained the power to declare some industries reserved and these workers, while they could be ballotted, were automatically granted exemption from call-up when they appealed to the Military Service Board. Minister of Defence James Allen (1855-1942) sent a notice to boards detailing this category as including coalmining, shearing, freezing work, shipping, and leather and boot manufacture. This created a two-tier hierarchy for appeals: men employed in production deemed central to the war effort were to be considered for automatic exemption, all others were not.[19] In 1917, as wheat became more expensive, the government added flour millers to the list; the Slaughtermen’s Union, too, was given the right to appeal on behalf of their members to keep up supplies of meat.[20]

Despite these measures, many industries suffered shortages of workers. At the outbreak of war, for example, freezing works and meat companies were almost immediately brought under the “commandeer” agreements with Britain. Despite this secure economic position, from the introduction of conscription, companies were involved in constant negotiations with the National Efficiency Board, the Recruiting Board and the Slaughtermen’s Union about exemptions for their workers. At a national conference in late 1917, Gear Meat Company representatives described the shortage of slaughtermen at their works, citing only sixty-nine men for “120 hooks” in the 1916-1917 season. Bringing on apprentices was almost impossible. “Where are the learners to be got from under the present conditions?” asked the delegate. In such a physically demanding occupation, “very few would have the physique to start before they were of military age”.[21] Tensions in the industry were exacerbated by the government’s decision to advertise for slaughtermen in Australia (where conscription had not been introduced), with some union delegates accusing the government of bringing in Australian workers to free up New Zealand men for conscription. By mid-1918, Gear Meat Company was at “breaking point” owing to labour shortages. A review by the Wellington Military Service Board in September deemed only those men who were experts, foremen or leading hands would be exempt from conscription. The lack of experienced men in charge of machinery at Gear had resulted in significant breakdowns over the 1917-1918 season and a shortage of “tripe cleaners” led to a shortage of “this useful commodity… greatly used by troopships, hospitals, at camps and also by the general population”. In addition, the coal shortage – in part caused by a shortage of miners as well as industrial action – made experienced firemen essential in the factory but, consequently, difficult to find.[22]

New Zealand was not entirely without industrial war production. Men in the Railway Department workshops in Wellington found their work substantially disrupted by the addition to their usual work of military production of wagons, tools and spare parts. Furthermore, in late 1918, the workshops produced disinfectant-spraying equipment for the Department of Health in an effort to combat the influenza pandemic.[23] There were experiments with the production of munitions but diverting resources from the building of locomotives was seen as counterproductive. There were already constant shortages of coal trucks during the war, in part due to the shortages of materials that had previously been imported from Britain, and the government’s view was that food (needing fuel and transport), rather than munitions, was New Zealand’s primary war industry.

It was ironic, and a cause of substantial tension (see section on Social and Political Tensions) that farming never enjoyed the protection of automatic or blanket exemption, despite NEB recommendations that it should.[24] Farmers argued that their war effort was in the fields of New Zealand and they deserved exempted status, but local Military Service Boards treated farmers very unevenly. Labour shortages were acute if farming organizations were to be believed, although census figures did not reflect large changes in the national agricultural workforce, reflecting the extent to which farming in New Zealand in this period was reliant on family labour.[25] Various schemes were proposed to ease the situation, including extending the summer holidays so that boys of high school age could help with the harvest. The solution in practice was that those left on farms, including women and children, worked harder.

At an aggregate level, the New Zealand workforce became both older and younger during the war, and also slightly more feminized. The return of veterans (see section Rehabilitating the Wounded) created some tensions as women workers were generally replaced, and ex-soldiers found themselves displaced in their workplaces by men who had been too young to serve. The economic slump of 1920-1921 also worked against the seamless reintegration of veterans into the workforce, and by the end of the decade, veterans were significantly represented among the unemployed of the 1930s depression, but their economic distress was shared with the population at large.

Voluntary work↑

A huge amount of economic activity during the war was carried out by volunteers. The formation of patriotic societies of all sorts, as well as the emergence of the New Zealand Red Cross (initially a branch of the British Red Cross) facilitated the incorporation of voluntary labour into the mobilization for war and the mitigation of its effects. Records of voluntary labour are fragmented but large numbers of schools, workplaces and sports teams as well as Red Cross groups performed voluntary labour around the country. By the end of the war there were 900 patriotic organizations registered with the government, and hundreds more Red Cross branches.

Voluntary workers provided essential materials for soldiers, medical units and hospitals. Alongside the ubiquitous socks, a wide range of clothing – especially pyjamas – was sewn and knitted. Medical equipment, such as wound pads, bandages, stump covers for amputees and hospital bed sheets were staples of unpaid workers’ output. One provincial Red Cross depot supplied 138,000 of these items in one month in 1916, which could be extrapolated over forty months of war to 5.6 million items from this one depot alone.[26] Women were the mainstay of this voluntary work, applying their existing sewing prowess and their newly learned knitting skills to outfitting soldiers and hospitals. Men, too, donated their time, mainly in bandage-making groups and as packers, with workers and sports teams volunteering in the evenings. These efforts were not without criticism, although it was muted. Competition between groups of men sometimes led to an emphasis on “records” and they were chastized gently for being “inclined to sacrifice the excellence of the work”.[27] Women were also rebuked in the popular press for neglecting their more immediate family’s sewing needs for those of men at the front.

Participation in voluntary work was driven by a range of reasons, from working-class women saving on postage to the front by sending their knitted or sewn items from patriotic society depots, to the sense of community created by a common project and communal gatherings. Families packed parcels for their own sons, and some regional associations sent scarves and socks to “their boys”, regiments formed in their provinces. This regional approach went against the generally agreed principle among New Zealand patriotic associations that articles should be sent to New Zealanders regardless of where they came from, and caused tensions among the executives of these groups. These debates signalled clearly, however, the sense of community ownership and connection that was served by voluntary labour.[28]

While the economic value of New Zealand’s voluntary labour is incalculable, its emotional value to those serving overseas is clear from the personal writings of soldiers and nurses. One volunteer nurse in Britain wrote to the Red Cross that the parcels arriving from New Zealand were “tangible proof of myriads of kind thoughts towards [the men] and aching desires to help them”. Sister Cora Anderson (1881-1962) wrote to her brother from the hospital in Cairo where she worked that while beds and mattresses filled every space including the verandas of her building, “the men say it is just like Heaven to be here”. Boxes of sheets and pyjamas had arrived at the hospital just the week before the influx of men. “I am sure,” she wrote, “those who sent them will never realise how much they mean to us.”[29]

Social and Political Tensions↑

While New Zealand was a relatively homogenous and egalitarian society, there were deep economic divisions between Maori and Pakeha. Compounding the wars of confiscation in the late nineteenth century, the operations of the Native Land Court had resulted in widespread landlessness among Maori, and had been seemingly regardless of individual iwi’s level of resistance to or collaboration with the British during the wars.[30] The focus of Maori politicians and leaders in the 1910s was firmly on improving health and educational opportunities for Maori, and on the “uplift” of their people. In addition, where Maori worked in occupations with unions, such as shearing and mining, higher wages were also on the agenda.[31] The trade union movement had strengthened in the early 20th century and the socialist newspaper, the Maoriland Worker, was established in 1910. The Worker quickly became known for its commitment to industrial unionism, international cooperation between unions and its pacifism.[32] There was opposition to the war from this sector of the socialist movement from the outset: it was regarded as a capitalist and imperialist war, and several trade union leaders were arrested and charged with sedition. They were among the 280 people charged with sedition during the war, for speaking out against government policy, the conduct of the war, and especially the introduction of conscription.

People from other political persuasions also objected to war, and then even more so to compulsion when the Military Service Bill was enacted in August 1916. Peace movements had arisen in New Zealand during the South African War (1899-1902), and maintained an anti-militarist stance throughout the introduction of compulsory military training for boys and young men. Indeed, the introduction of this scheme brought together advocates from the militant left and the liberal middle-class. The Anti-Militarist League, for example, which had sixteen branches by the end of 1911, was established by the editor of the Christian Herald, but the League joined with the socialist opponents of compulsory military training by 1912. The women’s suffrage movement of the late 19th century had also spawned several anti-militarist organizations such as the National Peace Council, the Canterbury Women’s Institute and, from 1915, the New Zealand branch of the Women’s International League of Peace and Freedom. Such organizations campaigned against the ongoing waging of the war, and assisted men who wished to avoid conscription. The meetings of such groups were often broken up by young men, or by soldiers, and the “gentlemen’s agreement” between the government and the mainstream press meant that anti-war activities were rarely reported.[33]

The stresses of wartime also saw increasing tension between urban and rural workers. These were to some extent historical tensions in that during the wharf workers’ strikes of 1913, farmers had been recruited as “special constables” to help break the picket lines. Farmers’ access to markets was being interrupted by the strikes and they were generally enthusiastic to help the government in its hour of need. During the war, however, farmers could not gain blanket exemption from conscription, while the very men they had opposed at the government’s behest in 1913 enjoyed automatic exemption from call-up. Farmers' newspapers increasingly published editorials opining that farmers were over-represented in the NZEF while the urban working and middle classes were not pulling their weight. Indeed, when the occupational statistics of the NZEF were collated by the government in October 1917, the Farmers’ Union Advocate published them in their entirety, demonstrating that while thousands of farmers and farm labourers had enlisted (over 18,000), only 5,543 clerks and 1,526 railway employees had done so, and only 140 each of lawyers and dentists.[34]

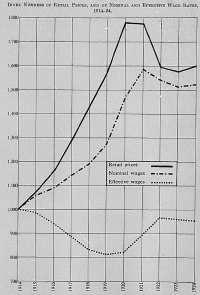

Industrial unrest grew in the later years of the war, especially as the cost of living outstripped wages. As early as March 1916, the women workers at the Wellington Woollen Mills struck in an effort to gain a small wage rise, or an end-of-year bonus, as the firm’s profits increased dramatically through war production. At the outbreak of war, women’s wages were only approximately 60 percent of men’s and by 1916 inflation was eating into those earnings. The striking workers claimed they were “working 60 hours a week for soldiers” but no longer earning a “living wage”.[35] The women were highly criticized for the strike because of and despite their involvement in a war-related industry. Their defenders pointed out that strikers “were the same girls who at the time of the [fundraising] carnival had given the whole of their time and money...and now they were called unpatriotic!”[36]

Wartime strikes were unusual in New Zealand, although coal miners engaged in a “go-slow” in 1917 for which they were threatened with removal of their exemption from conscription.[37] But in the immediate post-war period, industrial unrest was rife. Parliamentary investigations concluded that the shortage of housing was at the root of worker unrest, but the Maoriland Worker also identified the growing disparity between veterans’ benefits and those of civilian war workers and inflation. It reported in 1918 that the financial strain was evident in the “scrambles at jumble sales where the wives of honest working men fight to snatch up the left-off garments of other people”.[38]

Patriotic society records also reveal the increasingly difficult financial situation that low-income families faced as the war dragged on. Reports of “lady visitors” – those middle-class women appointed to inspect the living conditions of applicants – reveal soldiers’ dependants living in impoverished and overcrowded conditions in New Zealand cities.[39] That significant numbers of families and veterans themselves were still receiving assistance from patriotic societies into the 1930s demonstrates the deeply destabilizing effect of the war on family economies even in New Zealand.[40]

Anti-Alienism↑

As in other parts of the British Empire, the declaration of war changed the status of immigrants from Germany and Austria. Other Europeans too, such as Dalmatians and “Jugoslavs”, were targets of harassment and discrimination. In the first year of the war, the incidents of outright violence against those of German descent, such as the smashing of butchers’ windows in some towns, were countered with calls for tolerance and “common sense”.[41] Nonetheless, the Lutheran Church resolved to hold its services in English, and the largely German town of Sarau changed its name within weeks of the outbreak of hostilities to Upper Moutere, reflecting its position on the local river. The fragility of German residents’ positions in their town was increased in 1917 with the passage of the Registration of Aliens and the Revocation of Naturalisation Acts.

By this stage, too, over 500 men had been interned on one of three offshore island camps.[42] While some were members of the German military captured in New Zealand’s seizure of Samoa, the vast majority of internees were civilians, including Samoan servants of German colonial officials. As Somes Island internee Karl Joosten (1871?-?) complained in a letter to the Solicitor General, “None of us were caught in an act of war. Our only ‘crime’ was that we were of German nationality and happened to be in New Zealand when war broke out...Yet we are herded together...having to submit to autocratic military control”.[43]

Conditions on the island camps varied. There is evidence that some long-term internees on Somes Island in Wellington Harbour were able to earn a small income selling handkerchief boxes made from inlaid native timbers, shell and ivory.[44] But the official files also contain letters of complaint about the guards and commandant, and their treatment of internees. Regular beatings of some internees seem to have been common, as well as the withdrawal of visiting rights from family members.[45] The Revocation of Naturalisation Act was a source of particular insult for those of German ancestry who had become naturalized subjects. Even when Karl Joosten was paroled from the internment camp in 1919, he refused to sign the Aliens’ Register maintaining his protest that he had been naturalized in 1893 and had lived in New Zealand since he was fourteen years old.

Many men of German and Austrian descent were not interned but nonetheless suffered harassment and unemployment. George von Zedlitz (1871-1949), Professor of Modern Languages at Victoria College in Wellington, was dismissed in 1915 despite a concerted effort on the part of the College Council to protect him. After a dogged campaign by the press to have von Zedlitz removed from his position, the government passed the Alien Enemy Teachers Act in 1915 almost solely to force the college to bow to public opinion. In a much less celebrated case, the coroner in the North Island timber milling town of Dargaville attributed the suicide of a Croatian man to threats made against him by local townspeople, and ordered the police to investigate.[46]

Rehabilitating the Wounded↑

New Zealand, like other British settler colonies in the nineteenth century, had developed a strong “male breadwinner” ethos. Conservative and Labourist political forces saw as desirable, wages for white male workers that enabled them to keep their wives and children in a modest level of comfort. Enshrined in various pieces of wage legislation in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the “breadwinner wage” resulted in men’s wages being set at twice the level of women’s, and education acts in place by the end of the 1880s restricting the role of children, further embedded adult men as the key economic contributors in any family unit. The outbreak of war necessitated the removal of precisely these earners from their families. An elaborate system of separation allowances and allotments was developed in New Zealand, alongside an even more tortuous disability pension scheme. Some parts of the scheme, such as the allotment of part of a soldier’s pay, were revivals or variations on 19th-century practices: remittance payments from public works employees were one precedent, and the idea that a widow could only receive assistance if she was of “good repute” was another Victorian hangover still employed in the 1920s.[47] War pensions of all sorts were more generous than those for civilians and this situation eventually contributed to significant resentment on the part of those who had not been to war, especially if they had remained at home in crucial civilian jobs such as mining and farming.[48]

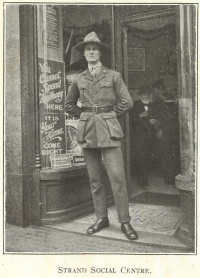

Rehabilitation of the wounded involved a wide range of initiatives from providing training to men while they were still in Britain to the provision of land in New Zealand to “soldier settlers”. The New Zealand rehabilitation hospital at Oatlands Park (an historic hotel in Surrey) was the first port of call for soldiers needing rehabilitation. There, they were provided with a wide range of what would become known as occupational therapy, including leather work, basket making, and needlework, taught by tutors from London’s Royal College of Art. Mechanical workshops and secretarial classes retrained men for new jobs, taking into account their disabilities.

Back in New Zealand, the government was slow to respond to the problem of returned-soldier unemployment, only establishing the Repatriation Department in 1919.[49] A collection of other less coordinated measures were implemented however, including amending university entrance and apprenticeship rules to institute the “soldier’s pass” that took account of the training and practical experience men had gained during the war.[50] As in other British dominions, the government also instituted a Soldier Settlement Scheme under which returned men could apply for farming land at favourable rates. While the Repatriation Department claimed to have found employment for over 27,000 returned men another 10,000 took up land under the Soldier Settlement Scheme.[51] The success or failure of the scheme has been the subject of debate over many decades of scholarship, but its foundations in the agrarian ideal and “breadwinner” masculinity are indisputable.[52] Far less attention has been given to the success of the repatriation schemes more generally, although those studies that have been conducted argue that the decision to close the Repatriation Department in 1922 was premature.[53]

War pensions for veterans were a significant part of the rehabilitation programme, and the most expensive. In 1920 the New Zealand government spent £1.87 million on disability pensions for soldiers, and widows’ and orphans’ pensions for soldiers’ dependants. In 1922, the government added a new category of pension allowing veterans and their families to apply for pensions on economic grounds. In 1924 just over 23,000 individuals received war pensions, with two thirds of recipients being returned soldiers. In addition, financial assistance continued to be sought by families and veterans from patriotic societies, established during the war to assist soldiers and their dependants into the 1930s and in extreme cases until the 1980s.[54]

Commemorations and Memorializing↑

Commemorating the dead and recognizing the service of New Zealanders began early in the war. Church, workplace and school honour boards recorded those who had enlisted, and public monuments began to be erected from 1915. Early examples include the memorial plaques in hospitals for the ten New Zealand nurses drowned in the sinking of the Marquette;[55] the Roseneath Primary School memorial in Wellington, which was erected in 1915 with the names of the dead inscribed in chronological order; and the 1916 erection of a flag pole at the New Zealand Railways Workshop in Petone, Wellington, which was donated by the New South Wales Railway Workers Union to symbolize the ”unity of Australian and New Zealand railwaymen in peace and war”.[56]

The imperial policy not to repatriate bodies also enmeshed New Zealand families in relationships with the Imperial (later Commonwealth) War Graves Commission, and required them to adapt their mourning practices. There were many continuities in those practices, but in the absence of bodies and graves, families created new memento mori using photographs and dead soldiers’ effects.[57] Grief destroyed some families and weighed on many others for decades after the conflict. By the end of hostilities 16,700 soldiers had been killed overseas.

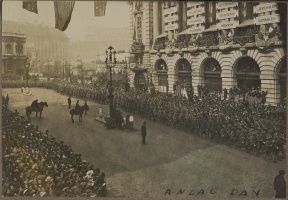

War memorials were erected in New Zealand as local memorials and, as in Australia, they were funded by public subscription not government grant. Many echoed the troopers’ memorials from the South African War, but the Great War memorials were so large in number and the lists of the dead so much more extensive, that they dwarfed earlier memorial cultures.[58] Most memorials took the form of an ornamental stone obelisk, statue or cenotaph. Very occasionally a community opted for the construction of a hall, a library or an avenue of trees. Oaks were used to create memorial avenues in Otago (South Island) and Ngawaka (North Island). Local war memorials were most commonly unveiled on either Anzac Day (25 April) or Armistice Day (11 November), with the civic presence of mayors, members of parliament and local veterans being equally, if not more important than the religious presence of the clergy. The secular nature of ceremonies reflected the architecture and design of memorials, very few of which contained Christian imagery.

The local nature of the memorials was combined with significant imperial sentiment. Wreaths commemorating Edith Cavell were common at early Anzac Day ceremonies, and the burial of the Unknown Soldier in London in November 1920 was also commemorated throughout New Zealand. The mayor of New Zealand’s southernmost town Invercargill announced to a crowded town square that the soldier might be “a native of any part of the Empire for aught they knew, and he might be the boy of any mother or father standing in the Post Office Square that day”.[59]

If war memorials blended the local and imperial, firmly national – or at least antipodean – sentiment was demonstrated through the establishment of 25 April as Anzac Day, commemorating the landings of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) on the Gallipoli peninsula. This did not exclude the expression of a range of imperial, racial and familial identities in the ceremonies: indeed, one of the strongest messages of early commemorations was that "British qualities of ‘valour, resource and tenacity’ had been safely transferred to the colonies."[60] The services were also an opportunity for mourners to "publicly express their pain in a socially acceptable fashion" and for communities to honour those who were bereaved.[61] Anzac Day ceremonies were remarkably uniform in their content during the 1920s and 1930s, and moved gradually away from overtly religious forms as New Zealanders became more comfortable with the new rituals. The anniversary was declared an official public holiday in 1916 and in the same year, the term “Anzac” was legally protected against commercial use. Cementing Anzac Day as a secular and flexible form of memorializing was the introduction of a dawn service in 1939.

The 1918 Influenza Pandemic↑

New Zealand society was traumatized by the influenza pandemic of 1918, compounding weariness from four years of war and anxiety about the welfare of serving family members. Those civilians who had been sheltered from battle by the geographic remoteness of New Zealand found themselves part of a medical campaign on an enormous scale. By the beginning of November the effects were widespread: schools and theatres were closed, and public places eschewed; armistice events were cancelled in an attempt to curb the spread of the virus; absenteeism in the workforce caused major disruptions to public transport and industry. The well-organized civilian war effort however, provided a scaffold for the citizens’ committees that formed to coordinate care for the ill, and replacement workers.[62] People too young for war service or war work, also now found themselves in the midst of a crisis that required them to nurse the sick, fill in for adult workers and face the bereaved in their communities.[63] Maori were disproportionately affected by influenza, being seven times more likely to die from the flu.[64] Remoteness from health care, relief workers and shops (leading to a shortage of supplies if the adults fell ill), as well as housing conditions that tended to be overcrowded, all contributed to Maori deaths. Unsurprisingly, the flu eclipsed the war for some communities and compounded its tragedy for others.[65]

Conclusion↑

Geographical remoteness did not shield New Zealand society from the Great War. While safe from battle, New Zealand society found itself enmeshed in the conflict, its waging and its aftermath. Membership of the British Empire brought responsibilities as well as advantages, and Pakeha New Zealanders were largely supportive – materially and sentimentally – of Britain’s participation in war. There was a wide range of opinion on the matter, however, and the state policed those opinions firmly. New Zealand was also not immune from the effects of large-scale death both in the war itself and in the concurrent influenza pandemic.

Kate Hunter, Victoria University of Wellington

Reviewed by external referees on behalf of the General Editors

Notes

- ↑ Olssen, Erik: Towards a New Society, in: Rice, Geoffrey (ed.): The Oxford History of New Zealand, Auckland 1992, p. 256.

- ↑ Boyack, Nicholas / Phillips, Jock / Malone, E.P.: The Great Adventure. New Zealand Soldiers Describe the First World War, Wellington 1988, p. 8.

- ↑ Gardener, W.J.: A Colonial Economy, in: Rice, The Oxford History of New Zealand 1992, p. 65.

- ↑ Evening Post (Wellington), 21 January 1916, p. 2.

- ↑ Crawford, John: “New Zealand is being bled to death”. The Formation, Operations and Disbandment of the Fourth Brigade, in: Crawford, John / McGibbon, Ian (eds): New Zealand’s Great War. Auckland 2007, p. 252.

- ↑ See Rogers, Anna: While You’re Away. New Zealand Nurses at War, 1899-1948, Auckland 2003; Rees, Peter: Other Anzacs. Nurses at War 1914-18, St Leonards, NSW 2008; Hallett, Christine E.: Veiled Warriors. Allied Nurses of the First World War, Oxford 2014.

- ↑ Baker, Paul: King and Country Call. New Zealanders, Conscription and the Great War, Auckland 1988, p. 43.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 109.

- ↑ Littlewood, David: “Should He Serve?” The Military Service Board’s Operations in the Wellington Provincial District, 1916-1918, MA thesis, Massey University 2010.

- ↑ Plumridge, Elizabeth / Carroll, Rowan: Policing the war. New Zealand Police Force 1914-1918, the invisible military machine, unpublished paper, Rethinking War Conference, Stout Research Centre, Victoria University of Wellington, 28-30 November 2013.

- ↑ Butterworth, Graham: Pomare, Maui Wiremu Piti Naera, in: Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, issued by the Ministry of Culture and Heritage, updated 30 October 2012. Online: http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/biographies (retrieved 27 September 2014).

- ↑ See Walker, Franchesca: “Descendants of a Warrior Race”. The Maori Contingent, Pioneer Battalion, and Martial Race Myth, 1914-19, in: War & Society, 31/1 (2012), p. 5.

- ↑ Buck, Peter / Hiroa, Te Rangi, cited in: Walker, “Descendants” 2012, p. 15.

- ↑ Keenan, Erin: A Maori Battalion. The Pioneer Battalion, Leisure and Identity, 1914-1919, unpublished Honours long research essay, Victoria University of Wellington 2007.

- ↑ See, for example, Sid Goodyear’s letter to his mother, in: Harper, Glyn (ed.): Letters from Gallipoli. New Zealand Soldiers Write Home, Auckland 2011, p. 54.

- ↑ Te Puea, in: King, Michael: Te Puea. Auckland 1977, p. 78.

- ↑ Baker, King and Country 1988, p. 220; Waitangi Tribunal, The Taranaki Report. Kaupapa Tuatahi, Wellington 1996, issued by the Waitangi Tribunal, online: http://www.justice.govt.nz/tribunals/waitangi-tribunal, 11.2. (retrieved 3 June 2014).

- ↑ See Nolan, Melanie: Breadwinning. New Zealand Women and the State, Christchurch 2000. Also Nolan, Melanie: Keeping the Home Fires Burning, in: Crawford / McGibbon (eds), New Zealand’s Great War 2007, pp. 493-515.

- ↑ Littlewood, “Should He Serve?” 2010, p. 29.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 30.

- ↑ Shearers and Slaughtermen, November 1916-March 1918, AD 82, Box 8 74, Archives New Zealand.

- ↑ Slaughtermen, Exemption of, NEB 1, Box 9 407, Archives New Zealand.

- ↑ Butterworth, Susan: Petone. A History, Petone 1988, p. 175.

- ↑ Despite farming being declared an essential industry by the NEB, farming men who appeared before Military Service Boards could not expect automatic exemption.

- ↑ Toynbee, Claire: Her Work and His. Family, Kin and Community in New Zealand, 1900-1930, Wellington 1995.

- ↑ Red Cross Record (official periodical of the New Zealand Red Cross), 17 August 1916.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 7.

- ↑ See Patrick, Rachel: An Unbroken Connection? New Zealand Families, Duty and the First World War, PhD thesis, Victoria University of Wellington 2014, pp. 54-56; Hunter, Kate / Ross, Kirstie: Holding on to Home. New Zealand Stories and Objects of the First World War, Wellington 2014, pp. 94-95.

- ↑ Unattributed letter reproduced in: Red Cross Record, 27 July 1918, p. 19. Sister Anderson to her brother, printed in: Kai Tiaki, The Journal of the Nurses of New Zealand, October 1915, p. 173.

- ↑ See, for example, Hill, Richard: State authority, indigenous autonomy. Crown-Māori relations in New Zealand/Aotearoa 1900-1950, Wellington 2004.

- ↑ Martin, John E.: Tatau tatau, one big union altogether. The shearers and the early years of the New Zealand Workers' Union, Wellington 1987.

- ↑ For more on the Maoriland Worker, see http://www.paperspast.natlib.govt.nz (retrieved: 17 September 2014)

- ↑ See Hutching, Megan: The Molloch of War: New Zealand Women who Opposed War, in: Crawford / McGibbon (eds): New Zealand’s Great War 2007; Anderson, John: Military Censorship in WWI: Its Use and Abuse in New Zealand, MA thesis, Victoria University of Wellington 1952; Davidson, Jared: Reds & Wobblies. Working-Class Radicalism and the State in New Zealand, 1915-1925, issued by Garage Collective, online: http://www.garagecollective.blogspot.co.nz (retrieved 20 September 2014).

- ↑ The report was reproduced in: Otago Daily Times (Dunedin), 6 October 1917, p. 8.

- ↑ Wanganui Chronicle, 7 September 1915, p. 8, on wage rates and working hours.

- ↑ Evening Post (Wellington), 27 March 1916, p. 3.

- ↑ Martin, J.E.: Blueprint for the Future? “National Efficiency” and the First World War, in: Crawford / McGibbon (eds): New Zealand’s Great War 2007, p. 526.

- ↑ Wahine, Maoriland Worker, 13 November 1918, in: Nolan: Keeping New Zealand Home Fires Burning 2007, p. 154.

- ↑ See, for example, Patrick, An Unbroken Connection? 2014, pp. 153-158.

- ↑ See, for example, Arthur Godfrey who received assistance into the 1940s, in: Hunter / Ross: Holding on to Home 2014, pp. 200-201.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 176-177.

- ↑ See Francis, Andrew: To Be Truly British We Must Be Anti-German. New Zealand, Enemy Aliens, and the Great War Experience, 1914-19, Oxford 2012.

- ↑ Joosten, Karl: letter to Hon Justice Chapman, 28 May 1918, Somes Island Internees’ Statements, MS-Papers-2071, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington.

- ↑ See, for example, inlaid boxes at the Museum of New Zealand/Te Papa Tongarewa, GH022533 and GH011328.

- ↑ O’Connor, Peter: Treatment of Aliens, MS-Papers- 5403-5, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington.

- ↑ Dargaville suicide reported in: Colonist (Nelson), 1 December 1914, p. 5. See also O’Connor, Treatment of Aliens.

- ↑ Nolan, Breadwinning 2000, pp. 71-72.

- ↑ See, for example, Nolan, Keeping the Home Fires Burning 2007, p. 514.

- ↑ See Parsons, Gwen: The many derelicts of the War. Great War veterans and repatriation in Dunedin and Ashburton, 1918 to 1928, PhD thesis, University of Otago 2009; Walker, Elizabeth: The living death: The repatriation experience of New Zealand’s disabled Great War servicemen, MA thesis, Victoria University of Wellington 2013, pp. 123-124.

- ↑ Clarkson, Coralie: The reality of return: Exploring the Experiences of World War One Soldiers after Their Return to New Zealand, MA Thesis, Victoria University of Wellington 2011, pp. 59-60.

- ↑ Parsons, The many derelicts of the War 2009, pp. 89, 91. Gould, Ashley: Proof of Gratitude? Soldier Land Settlement in New Zealand after World War I, PhD thesis, Massey University 1992, p. 286.

- ↑ Roche, Michael: Empire, duty and land: Soldier settlement in New Zealand, 1915-1924, in: Proudfoot, Lindsay J. / Roche, Michael M. (eds): (Dis)Placing Empire: Renegotiating British Colonial Geographies, Aldershot 2005, pp. 135-154; Gould, Proof of Gratitude? 1992.

- ↑ See Parsons, The many derelicts of the War 2009; Walker, The living death 2013; Clarkson, The reality of return 2011.

- ↑ Hunter / Ross, Holding on to Home 2014, pp. 200-201; Nolan, Breadwinning 2000, pp. 69ff.

- ↑ See, for example, the letters to the editor, in: Kai Tiaki, October 1916, p. 205.

- ↑ Petone railway station war memorial, issued by Ministry for Culture and Heritage, online: http://www.nzhistory.net.nz/media/photo/petone-railway-station-war-memorial, updated 4-Sep-2014 (retrieved 20 October 2014).

- ↑ Hunter, Kathryn M.: “Sleep on dear Ernie, Your Troubles are O’er”: A glimpse of a mourning community, Invercargill, New Zealand, 1914-1925, in: War in History, 14/1 (2007), pp. 36-62; Callister, Sandy: Stabat mater dolorosa. Death, Photography and Collective Mourning, in: New Zealand Journal of History, 41/1 (2007), pp. 3-26; Hunter / Ross, Holding on to Home 2014, Chapter 8.

- ↑ See Maclean, Chris / Phillips, Jock: The Sorrow and the Pride. New Zealand War Memorials, Wellington 1996.

- ↑ Southland Times (Invercargill), 12 November 1920, p. 5, cited in: Hunter, “Sleep on dear Ernie” 2007, p. 57.

- ↑ Worthy, Scott: A debt of honour. New Zealanders’ first Anzac Days, in: New Zealand Journal of History, 36/2 (2002), pp. 189.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 191.

- ↑ Rice, Geoffrey: Black November. The 1918 Influenza Pandemic in New Zealand, 2nd edition, Christchurch 2005, pp. 71-73.

- ↑ Bennett, Charlotte: “Now the war is over, we have something else to worry us”. New Zealand children’s response to crises 1914-18, in: Journal of the History of Childhood and Youth, 7/1 (2014), pp. 19-41.

- ↑ Rice, Black November 2005, p. 159.

- ↑ See ibid., pp. 159-183 for effects on Maori throughout New Zealand. For local experience, see Matthews, Suzanne: “The enemy within our gates”. The 1918-19 influenza epidemic in the Waikato, M.Soc.Sc. Dissertation, Waikato University 2001.

Selected Bibliography

- Baker, Paul: King and country call. New Zealanders, conscription, and the Great War, Auckland 1988: Auckland University Press.

- Bennett, Charlotte: 'Now the war is over, we have something else to worry us'. New Zealand children’s responses to crises, 1914-1918, in: The Journal of the History of Childhood and Youth 7/1, 2014, pp. 19-41.

- Crawford, John / McGibbon, Ian C. (eds.): New Zealand's Great War. New Zealand, the Allies, and the First World War, Auckland 2007: Exisle Publishing.

- Fenton, Damien: New Zealand and the First World War, 1914-1919, Auckland 2013: Penguin.

- Francis, Andrew: 'To be truly British we must be anti-German'. New Zealand, enemy aliens, and the Great War experience, 1914-1919, Oxford; New York 2012: Peter Lang.

- Hallett, Christine E.: Veiled warriors. Allied nurses of the First World War, Oxford 2014: Oxford University Press.

- Hill, Richard S.: State authority, indigenous autonomy. Crown-Māori relations in New Zealand/Aotearoa 1900-1950, Wellington 2004: Victoria University Press.

- Hunter, Kate: ‘Sleep on dear Ernie, your battles are o’er.’ A glimpse of a mourning community. Invercargill, New Zealand, 1914-1925, in: War in History 14/1, 2007, pp. 36-62.

- Hunter, Kate / Ross, Kirstie: Holding on to home. New Zealand stories and objects of the First World War, Wellington 2014: Te Papa Press.

- Maclean, Chris / Phillips, Jock: The sorrow and the pride. New Zealand war memorials, Wellington 1990: GP Books.

- Monger, David / Pickles, Katie / Murray, Sarah (eds.): Endurance and the First World War. Experiences and legacies in New Zealand and Australia, Newcastle upon Tyne 2014: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Nolan, Melanie: Breadwinning. New Zealand women and the state, Christchurch 2000: Canterbury University Press.

- Parsons, Gwen A.: 'The many derelicts of the War'? Great War veterans and repatriation in Dunedin and Ashburton, 1918 to 1928, thesis, Dunedin 2008: University of Otago.

- Patrick, Rachel: An unbroken connection? New Zealand families, duty, and the First World War, thesis, Wellington 2014: Victoria University of Wellington.

- Phillips, Jock / Boyack, Nicholas / Malone, E. P. (eds.): The great adventure. New Zealand soldiers describe the First World War, Wellington; Winchester 1988: Allen & Unwin; Port Nicholson Press.

- Rogers, Anna: While you're away. New Zealand nurses at war 1899-1948, Auckland 2003: Auckland University Press.

- Walker, Franchesca: ‘Descendants of a warrior race’. The Maori Contingent, New Zealand Pioneer Battalion, and Martial Race Myth, 1914–19, in: War & Society 31/1, 2012, pp. 1-21, doi:10.1179/204243411X13201386799091.

- Worthy, Scott: A debt of honour. New Zealanders' first Anzac days, in: New Zealand Journal of History 36/2, 2002, pp. 185-200.