Pre-World War I Background↑

The period just before America entered World War I, from 1914-1916, was one in which many Americans opposed the Unites States’ entry into the Great War. By 1917, widespread opposition to American participation in World War I had increased significantly, as anti-war sentiments confronted a burgeoning patriotism. A few hardcore activists, however, remained committed enough to the cause of peace so as to be willing to face harassment and serve time in prison.

Religious Mobilization against the War↑

Religious convictions motivated the majority of American pacifists and conscientious objectors. Before 1914, the American peace movement had been an almost completely Protestant endeavor. Clergy, laymen and -women dominated American pacifism through organizations like the American Peace Society. While traditional peace churches such as the Quakers played a large role in the First World War's peace movement, other denominations - including the Unitarians, Congregationalists, Episcopalians, and Methodists - were involved as well.

While large antiwar groups such as the American Peace Society existed before the outbreak of World War I, several national pacifist organizations were formed after 1914. The Christian Socialist League was established by the Episcopalian lay-members Fannie May Witherspoon (1885-1973) and Tracy Mygatt (1885-1973). That same year, industrialist Andrew Carnegie (1835-1919) funded the creation of the Church Peace Union, an ecumenical organization that promoted international and ecclesiastical harmony. The Church Peace Union promoted other peace groups such as the American Fellowship of Reconciliation and the American League to Limit Armaments. In 1916, the Church Peace Union hosted a massive "Conference of Peacemakers" that brought together many of the largest antiwar groups, including the Women’s Peace Party, the American Peace Society, the League to Enforce Peace, the American Neutral Conference Committee and the World Peace Foundation. Two principal aims of American pacifist organizations were to end fighting in Europe and to promote the United States' neutrality.

Selective Service Act↑

When Congress passed the Selective Service Act in May 1917, many pacifists transitioned to a new status, namely that of conscientious objectors. The Act exempted members of well-established religious groups whose doctrines forbade participation in combat. Uncertainty in local draft boards over which religious sects qualified for exemptions frequently resulted in arbitrary rulings in conscientious objection claims. There was initially no provision in the Selective Service Act for non-religious objections for military service. Thus individuals objecting to the war on humanitarian or political grounds and German Americans who detested fighting their former countrymen stood without any legal protections of their objections to fighting.

Conscientious Objectors in Limbo↑

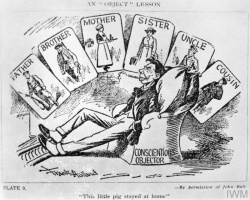

In addition to the haphazard granting of combat exemptions, the federal government failed to outline what alternative services conscientious objectors might perform. The outcome was that for nearly a year, the 20,000 men who had been granted conscientious objector status by local draft boards were sent to army training camps until President Woodrow Wilson (1856-1024) designated alternative forms of service. While the War Department instructed Army commanders to segregate and to treat conscientious objectors considerately, life in the camps was hard. Humiliation, hazing and cajoling resulted in 16,000 certified conscientious objectors renouncing their combat exemptions and taking up arms. The Civil Liberties Bureau protested their treatment, and in March 1918 President Wilson finally designated alternative forms of service available to conscientious objectors. It was also in March that local draft boards were allowed to consider non-religious conscience objections.

Religious Motivations↑

Religious beliefs formed a primary motivating factor for conscientious objectors. Out of the 65,000 total of men claiming conscientious objector status, the large majority were motivated by some form of religious objection. Of the 4,000 men who refused to participate in the war in any capacity, roughly 90 percent were Christian pacifists. Many conscientious objectors represented long-standing pacifistic denominations such as the Society of Friends (Quakers) and the Mennonites. Other religious groups, including African American Pentecostals, Jehovah’s Witnesses and the Molokan Church of Arizona, sought to claim exemptions from military service. In addition to denominations which claimed exemptions from military service, some individuals from mainline churches such as the Episcopalians and Presbyterians also sought conscientious objector status.

Secular Motivations↑

About 10 percent of conscientious objectors objected on political or humanitarian grounds. Some socialists and the radical Industrial Workers of the World (I.W.W.) unionists sought exemptions from combat duty and opposed the war because they saw it as supporting wealthy businessmen and the capitalist system. A small number of anarchists rejected the right of the state to compel them to fight in a conflict they opposed. Finally some German Americans refused to fight against their former countrymen. When Congress passed the Espionage Act in 1917 and the Sedition Act one year later, radical socialists and anarchists - many of whom were immigrants - faced imprisonment and deportation.

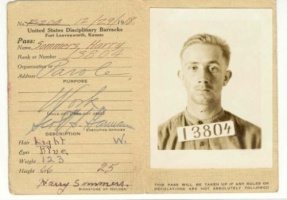

Absolutists↑

While the majority of conscientious objectors agreed to fulfill some sort of alternative service, about 4,000 were imprisoned for refusing to participate in the war at all. These "absolutists" faced much harsher punishment than other conscientious objectors. Some of them, such as the chief of the Civil Liberties Bureau Roger N. Baldwin (1884-1981), were able to have their cases tried in civil courts. Many, however, were not so fortunate. Over 500 absolutist conscientious objectors were inducted into the army, court-martialed and brought before a military tribunal. Nearly all were found guilty and sent to military prisons where they often faced brutal treatment. While imprisoned war resisters had little recourse to justice, two military officers responsible for severely beating conscientious objectors in Camp Funston, Kansas, received mild punishments and honorable discharges.

Slacker Raids↑

An estimated 300,000 conscription age-men, or "slackers" as they were referred to by the administration, failed to register for the draft. While little was initially done to find these men, in March 1918 the Justice Department along with the American Protective League initiated the practice of so-called "slacker raids." These raids represented a cooperative effort between the 250,000 volunteers of the American Protective League and local and federal authorities. The volunteers of the American Protective League would descend on a city, interrogate suspected draft evaders and turn in those who could not produce draft registration cards to local police for further questioning. The first slacker raid took place in Pittsburgh. Larger raids took place in Chicago, Boston, New York, and Northern New Jersey. The New Jersey raid on its own resulted in the apprehension of over 13,000 young men who had failed to register for the draft.

World War I and Civil Liberties↑

Finally, World War I represented a severe challenge to American civil liberties. Delays in defining legitimate conscience objects or suitable forms of alternative service resulted in limited access to military exemptions and to approved conscientious objectors being held in military training camps. Conscientious objectors in the camps faced harassment and pressure to accept combat duty, and those who were imprisoned faced brutal conditions including torture and physical abuse. Treatment of conscientious objectors in prisons and military camps included solitary confinement, forced exercise, short rations, being chained to the bars of their cell so that they were forced to stand for longs periods of time, verbal harassment by guards and military authorities and beatings. The Espionage and Sedition Acts limited the free speech rights of both Americans who opposed the war and those seeking exemptions from military service. A few religious denominations and secular organizations such as the Bureau of Legal Advice and National Civil Liberties Bureau sought to protect the right of conscientious objectors.

Luke Schleif, University of Missouri

Section Editor: Lon Strauss

Selected Bibliography

- Capozzola, Christopher Joseph Nicodemus: Uncle Sam wants you. World War I and the making of the modern American citizen, Oxford; New York 2008: Oxford University Press.

- Early, Frances H.: A world without war. How U.S. feminists and pacifists resisted World War I, Syracuse 1997: Syracuse University Press.

- Marchand, Charles Roland: The American peace movement and social reform, 1898-1918, Princeton 1973: Princeton University Press.

- Murphy, Paul L.: World War I and the origin of civil liberties in the United States, New York 1979: Norton.

- Preston, Andrew: Sword of the spirit, shield of faith. Religion in American war and diplomacy, New York 2012: Alfred A. Knopf.