Military Career↑

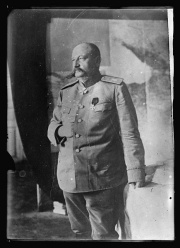

Of noble birth, Nikolaĭ Yudenich (1862-1933) began his military career upon graduating in 1881 from the Aleksandrovskoe Military School and, in 1887, from the Nikolayevskaĭa General Staff Academy. Promoted to junior captain, Yudenich served on the General Staff in the Warsaw, Turkestan, and Vilna military districts until 1902. During the Russo-Japanese War in 1904-1905, his 18th Infantry regiment’s performance in the battle near Mukden earned him a gold sword for bravery. Promoted to major general in 1905, he was appointed quartermaster general of the Caucasus Military District headquarters in 1907. In 1912, he was promoted to lieutenant general and had risen to become chief-of-staff of the Caucasus Military District the following year. Nearly two months after the outbreak of World War One, Yudenich was appointed chief-of-staff of the Russian Caucasus Army.

First World War↑

During the war, Yudenich distinguished himself as the most consistently successful Russian general. A tireless and efficient worker, he transformed the Caucasus Front into a source of continual good news and figured prominently in Russian wartime propaganda for the series of defeats he was able to inflict upon the Turks, notably at Sarıkamış and Erzurum.

In light of the order for retreat issued by the deputy commander of the Russian Caucasus Army in December 1914, Yudenich insisted on defending Sarıkamış, firmly maintaining that the retreat might lead to disaster. He retained his positions south of Sarıkamış and then moved his troops up into new positions from which they could encircle the Ottoman forces. In January 1915, Yudenich was put in command of the main grouping of the Russian Caucasus Army. After carrying out a series of successful attacks in this capacity, he was able to annihilate the remnants of the Ottoman forces inside Russian positions. For his role in the victory at Sarıkamış, Yudenich was promoted to commander of the Russian Caucasus Army with the rank of general of the infantry.

In one episode during the summer of 1915, when his Fourth Caucasian Army Corps suffered defeat near Malazgirt west of Lake Van, Yudenich chose not to reinforce the depleted units, as the standard military practice dictated, but secretly formed a strategic reserve force instead. He held the force back for the propitious moment and then crushed the advancing Turks with a flank attack. When Yudenich realised that he could face massive Ottoman reinforcements after the impending Allied evacuation from Gallipoli in October 1915, he averted this danger by a series of spoiling operations conducted during the first half of the following year. An unflappable, innovative, and daring strategist, he sought to weaken and disconcert his opponents, not just seize territory. After capturing a territory, he would characteristically pause to consolidate gains and construct fortified areas, and not push forward on the offensive.

Throughout 1916, Yudenich continued making military gains, capturing Erzurum in February, Trabzon in April, and Erzincan in July, thus completely outflanking the Ottoman forces. His qualities of a great commander were most manifest during the Erzurum Offensive, one of the most daring offensives launched by the Russian army on the Caucasus Front. Comprised of an inner core of several forts and batteries, the fortress of Erzurum was well defended by trenches and wire covering the ground between the forts. The Russians, who had to attack across rugged terrain covered in a thick layer of snow, had only a slight advantage in numbers. Thanks to Yudenich who personally devised the plan of attack, the Russian assault made rapid progress and was crowned with success. The fall of Erzurum, allegedly the most impregnable Ottoman stronghold in eastern Asia Minor, brought Yudenich considerable popular and professional esteem.

By early 1917, Yudenich’s Caucasus Army was the most efficient fighting force of all the Russian armies in the war. During the troubled revolutionary events in February, Yudenich behaved prudently, refraining from excessively supporting the advocates of the weakening Romanov dynasty or publicly sympathising with the abjured tsar, Nicholas II, Emperor of Russia (1868-1918). In March, he regained overall command of the Caucasus Front, but refused to renew the advance of the Expeditionary Corps in Persia towards Mesopotamia and ordered two army corps to withdraw to better quartering areas. He hoped such a move would dampen revolutionary fervour and maintain fighting efficiency and morale among his troops. On 7 May, Russia’s Provisional Government removed him from command for insubordination, and on the orders from Minister of War and Navy Alexander Kerenskiĭ (1881-1970) , he retired from active service.

Russian Civil War↑

Later in May, Yudenich returned to Petrograd, where he found revolutionary chaos reigning, and then went to Moscow, where he established contact with clandestine officers’ groups. However, the second revolution that shook Russia in October forced him to go into hiding and flee to Finland the following year. There, fate brought him to commander of the White Guard Carl Mannerheim (1867-1951), whom Yudenich knew from his time in the General Staff Academy. Their exchanges led him to the idea of launching an armed struggle against the Bolsheviks from abroad. To make this happen, he connected with the Russian Committee, a counter-revolutionary group based in Helsingfors comprised of top tsarist bureaucrats, industrialists and financiers. In January 1919, the Committee nominated Yudenich as leader of the White movement in northwest Russia with absolute powers.

If during the February Revolution Yudenich had played a “waiting game,” being careful not to commit himself to any particular party, faction or reformers of the late tsarist regime, during the Russian Civil War he emerged as a decided reactionary. Seeing the extensive destruction that had shaken the very foundations of the unity of his country, he became a staunch supporter for the restoration of monarchy and an undivided empire. It was only with the greatest difficulty that he was persuaded to concede the national independence of Estonia and Finland, two former Russian governorates, without which he could hardly expect to win Petrograd.[1]

Yudenich spent most of the first half of 1919 assembling an army and procuring military supplies for an autumn offensive on Petrograd. In May, the Russian Committee was replaced by the Political Convention, a deliberative body intended to prefigure the government of Russia’s northwestern regions. The Convention dispatched Yudenich to Estonia from where his troops were to march on the Russian capital. In June, Supreme Ruler of Russia Alexander Kolchak (1874-1920) recognized Yudenich as commander-in-chief of all armed forces in Russia’s northwest. Kolchak even provided funds to pay and equip Yudenich’s newly organised Northwestern Army, which by the time of the offensive numbered 18,500 men, 6 tanks, 4 armoured trains, 4 armoured cars, and 53 artillery pieces.[2]

Launched in early October, the offensive advanced rapidly and extended as far as the outskirts of Petrograd. However, Commander of the 3rd Division Daniil Vetrenko (1882-1949), in circumstances that are still unexplained, failed to carry out Yudenich’s order to cut off the Nikolayevskaĭa railway from Moscow to Petrograd,[3] which allowed Chairman of the Revolutionary Military Council Leon Trotsky (1879-1940) to send in massive reinforcements to prevent the fall of the city. As a result, the Reds were able to push Yudenich’s troops back into Estonia, where they were interned in camps, partly in the open air, before being disbanded by their commander’s last order, issued on 22 January 1920.[4]

Arrest, Exile and Death↑

A few days later, Yudenich was accused of an attempt to escape with the remaining army funds. He was arrested by several adventurist Russian officers in league with the Estonian police. Their misconduct was protested and, after the intervention of the commander of the British squadron anchored at Revel, he was released and allowed to settle into exile in France. During his remaining thirteen years on the French Riviera, he largely shunned White émigré politics, preferring instead to give presentations on military arts. Nikolaĭ Yudenich died at Saint-Laurent-du-Var,[5] near Nice, on 5 October 1933.

Tigran Martirosyan, University of Amsterdam

Section Editor: Pınar Üre

Notes

- ↑ Luckett, Richard: The White Generals. An Account of the White Movement and the Russian Civil War, London 1971, p. 304.

- ↑ Anonymous: Oktiabr’skoe nastuplenie na Petrograd i prichiny neudachi pokhoda: zapiski bielago ofitsera [The October attack on Petrograd and the reasons for the failure of the campaign. Notes of a White officer], Finland 1920, p. 13.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 56.

- ↑ Vetrenko’s insubordination was not the only reason for failure. Other reasons were overextension, Estonian authorities’ overtures to the British and then the Bolsheviks, the British reneging on their promise to provide military assistance and later collaborating with the Bolsheviks, the disobedience of Commander of West Russian Volunteer Army Bermondt-Avalov, and the Reds’ superiority in men and equipment.

- ↑ Russian authors Shishov and Portugal’skiĭ et al. suggest Cannes as place of Yudenich’s death.

Selected Bibliography

- Allen, William Edward David / Muratoff, Paul: Caucasian battlefields. A history of the wars on the Turco-Caucasian border, 1828-1921, Cambridge 1953: Cambridge University Press.

- Kornatovskiĭ, Nikolaĭ Arsen’evich: Bor’ba za krasnyĭ Petrograd (The struggle for red Petrograd), Leningrad 1929: Krasnaia gazeta.

- Korsun, Nikolaĭ Georgievich: Pervaia mirovaia voina na Kavkazskom fronte, operativno-strategicheskii ocherk (The First World War on the Caucasus Front. An operational-strategic sketch), Moscow 1946: Voennoe Izdat. Ministerstva Vooruzhennykh Sil Soiuza SSR.

- Luckett, Richard: The White generals. An account of the White movement and the Russian Civil War, London 1971: Routledge.

- Portugal’skiĭ, Richard Mikhaĭlovich / Alekseev, P.D. / Runov, V.A.: Pervaĭa︡ mirovaĭa︡ v zhizneopisaniĭa︡kh russkikh voenachal’nikov (The First World War in the life stories of Russian military commanders), Moscow 1994: Elakos.

- Shishov, Alexeĭ Vasil’evich: Yudenich. General suvorovskoĭ shkoly (Yudenich. A general of Suvorov’s schooling), Moscow 2004: Veche.

- Tucker, Spencer (ed.): Yudenich, Nikolai Nikolaevich (1862-1933): The European powers in the First World War. An encyclopedia, New York 2013: Routledge, pp. 761-762.