Foundations of Occupation (November 1914-June 1916)↑

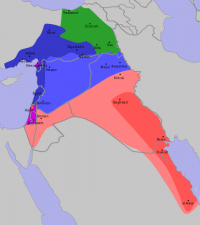

The Russian Empire began occupying Ottoman territory from the very start of the war, taking the region around Bayezid (Doğubayazıt) in the fall of 1914. Continued Russian expansion into Ottoman territory proceeded at a different pace across the front; in the south, the Russian army fought for Van in the spring and summer of 1915, while in the north, it had to recover from an initial Ottoman assault but captured Erzurum and Trabzon in February and April 1916, respectively. Unlike the other Allied occupations of Ottoman territory during the war, including the Levant and Mesopotamia, and later Istanbul, the Russian occupation took place in territorially contiguous Ottoman provinces. The question of annexation to the empire thus arose immediately. As early as 1912, the Russian Foreign Ministry had expressed an interest in leading a project of “oversight” over governance of the Ottoman Empire’s eastern provinces, which featured a significant Armenian and Kurdish population. During the war, however, the Russian government did not exhibit a common approach toward the annexation of the region, which was often called “Turkish Armenia.” A plan issued by Foreign Minister Sergeĭ Sazonov (1860-1927) in February 1915 entitled “Basic Principles for the Future Ordering of Armenia” was simply a more robust restatement of pre-war calls for Russian oversight. Other elements of the Russian government in Petrograd and Tiflis (Tbilisi), most notably the agriculture ministry and the commander of the Russian army in the Caucasus Nikolaĭ Iu͡denich (1862-1933), pushed for more assertive measures, including direct annexation by Russia or settlement by pro-Russian elements. Armenian nationalists, most notably members of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation, supported plans for maximum Armenian autonomy under Russian protection.

Territories under occupation were initially administered by officers stationed there. Nevertheless, lack of personnel, among other considerations, forced these officers into making ad hoc arrangements during the first year of occupation. These included calling on the help of neighboring civilian administrators on Russian territory and in some cases relying on local Armenian organizations. Between December 1914 and April 1915, Sirakan Tigranyan (1875-1947), later foreign minister of the Republic of Armenia, convinced local Russian commanders for permission to establish an Armenian administration in the Alashkert (Eleşkirt) region with a minimum of interference from the Russian military. Much better known is Russia’s approval of Aram Manukyan’s (1879-1919) ill-fated Armenian administration in Van between May and July 1915. Russian administration in the occupied territories began to crystalize in the fall of 1915 with the circulation of the provisional “Directives for district heads in the regions of Turkey occupied by right of war.” The directives temporarily granted officers in charge of districts the prerogative of a governor-general, defined their main tasks, and delineated district boundaries.

The Provisional Military Governorate-General (June 1916-April 1917)↑

Discussions in the spring of 1916 between Sazonov and France’s ambassador to Russia Georges Maurice Paléologue (1859-1944) drew Russia into the Sykes-Picot agreement and secured the Allies’ consent for Russia’s postwar annexation of the occupied territories. Together with Russia’s capture of Erzurum, the region’s major city, the Sazonov-Paléologue agreement accelerated Russian administrative organization of the occupied territories.

On 18 June 1916 (Julian calendar: 5 June 1916), Russian command issued Decree No. 739, “Provisional Guidelines for the Administration of the Regions of Turkey Occupied by Right of War.” The guidelines established a “provisional military governorate-general” under a military governor-general. The territory administered by the military governor-general would encompass the entire area lying from the state borders of the Russian Empire to the zone of active operations. The administrative center of the military governorate-general remained in Tiflis, outside the occupied territories. The large governorate was subdivided into eight administrative districts, which rose to twenty-nine by the end of the occupation. Trabzon, the strategically important westernmost district on the Black Sea coast, received the status of “fortified region”; here, military command retained more direct control over administration.

Administrative Aims and Policies↑

Recent historiography posits that immediate military needs like provisioning, and not the long-term development of the occupied territory or its eventual annexation, were the primary guide in shaping Russian occupation policies after 1916. Yet the military’s need for immediate agricultural production clashed with its need for a frontline population unwaveringly loyal to Russian interests, since the population available for agricultural labor consisted largely of Kurds and Armenian refugee returnees—neither of whom the Russian administration held in particularly high esteem. As a result, the Russian administration became preoccupied with control of the mobility and makeup of the region’s population. The nationalization of lands emptied by refugees or deportees allowed Russian officials to rent these lands, providing both a source of income and a modicum of control over who settled where. “Suspect populations” were deported to the interior or drafted to work in mining and the maintenance of transportation infrastructure.

Historians have also focused on the nationality issue. On paper, the military governor-general was charged with “protecting the life, honor, property, and religious and civic liberty of the population, as well as the provisioning of the latter, under full equality before the Russian government for all nationalities.”[1] In reality, most nationalities could feel disadvantaged by rule under the military governorate-general. First, with postwar annexation now likely, Russian officials after 1916 became more wary of nationalism and took measures to limit Armenian influence in the region. The military governorate-general pointedly refrained from calling the occupied territories “Turkish Armenia” and all but prohibited the return of Armenian refugees who had fled from the region during the genocide. Military governor-general Nikolaĭ Peshkov (1857-?) justified the de facto ban by arguing that “the premature return of refugees often results in undesirable panic and needless sacrifice, both in human and material terms.”[2] Meanwhile, though all populations near the front were subject to deportations, Kurds were among those most targeted for mass removal and bore the brunt of both state violence and decentralized violence in the occupied territories. Finally, the downgrading of the status of Greek Orthodox community leaders in Trabzon also caused resentment.

Humanitarian Work in the Occupied Territories↑

Before the ban on refugee resettlement, the Armenian Genocide and the Russian army’s advance into Ottoman territory had already precipitated a mass uprooting of populations in both directions. Russian administrators had registered approximately 367 thousand refugees in the Caucasus by late 1916. In the Ottoman territories occupied by the Russian Empire, a number of state-supported organizations and fundraising campaigns worked to alleviate refugee suffering. A prominent effort, the so-called Tatiana Committee, was sponsored by the daughter of the tsar. Other significant campaigns were led by the Russian Society of the Red Cross and the All-Russian Union of Zemstvos and Towns. Ethnically-based aid organizations, both Armenian and Muslim, filled a gap in support that the state was unwilling or unable to provide, but they also served as a cover for nationalist mobilization that was otherwise banned.

The Commissariat-General (April 1917-March 1918)↑

The Provisional Government established in Petrograd after the February Revolution was decidedly more sympathetic to Armenian national demands than its predecessor. It now officially called a large part of the occupied territories “Turkish Armenia,” for example, and consulted heavily with Dr. Yakov (Hakob) Zavriev (1866-1920), a well-known Armenian nationalist, on the future of the region. An administrative reorganization of the occupied territories, approved by the Provisional Government on 9 May 1917 (Julian calendar: 26 April 1917), corresponded by and large with Zavriev’s own proposal. The authority of the military governor-general would be assumed by a “commissar-general,” whose administration would be subordinated directly to the Provisional Government. On 28 May 1917 (Julian calendar: 15 May 1917), the government appointed Lieutenant-General Pëtr Ivanovich Aver’ia͡nov (1867-1937), a published orientalist, as “commissar-general of Turkish Armenia and other regions of Turkey occupied by right of war.” The occupied territories were divided into four provinces (Trabzon, Erzurum, Bitlis, and Van). These provincial administrations were served primarily by Armenians; in Van and Bitlis, they were “without exaggeration an Armenian monopoly.”[3]

Administrative Aims and Practices↑

Like the pre-revolutionary government, the Provisional Government’s main concerns in the occupied territories were to revive agricultural production, to deal with the refugee crisis, and to ensure logistical support for the front in the face of increasing scarcity. While the Provisional Government also never officially called for an annexation of the occupied territories, it did facilitate Armenian settlement of the region—not only for former residents who had fled to Russia during the war but also for Armenians of Ottoman subjecthood wishing to settle there. Extant Muslim inhabitants of the region would be guaranteed protection by law, but those who had fled with the retreating Ottoman army would not be allowed to return until a special directive was issued on the matter.

While the most widely cited work on the occupation claims that the February Revolution only effected a slight change in nomenclature rather than a serious change in local administration,[4] more recent research suggests that this is not the case. Similar to the situation in the Caucasus, executive committees of soldiers’ soviets initially asserted control over local administration; the power-sharing arrangements that emerged could vary. The executive committee of Of, for example, seemingly continued to usurp the local commissar’s authority through 1917, issuing directives on sale of provisions in the market and on interreligious harmony.[5]

The Final Months↑

The final months of Russian occupation were characterized by a struggle for control of the increasingly demoralized occupying army. One contender was the Bolshevik party. Bolsheviks spread their influence among Russian units in the occupied territories by establishing “military-revolutionary committees” for the regions of Trabzon, Erzurum-Erzincan, Van, and parts of northern Iran in late 1917. The Bolsheviks had, as early as the spring of 1917, demanded an end to the occupation and encouraged the establishment there of an independent Armenian Republic “supported” by Russia; the promotion of Armenian self-determination became official Soviet policy with the 12 January 1918 “Decree on Turkish Armenia.”

National organizations also took advantage of the worsening situation on the front. Leading Armenians began organizing Armenian troops in the occupied territories in 1917. By December of that year, they, along with Georgian units, were incorporated into the Russian Caucasus Army and soon began taking over the defense of fortified positions. The use of regular and irregular Armenian units on occupied territories had seriously exacerbated interethnic tensions. After a cease-fire was signed between the Russian and Ottoman armies on 18 December 1917, observers feared a full-out conflict between Armenian armed forces and Armenian returnees against Ottoman-backed Kurds and Muslim returnees.

Two simultaneous developments precipitated the end of the Russian occupation. The de jure end of the occupation was arranged between Bolshevik and Central Powers at Brest-Litovsk between December 1917 and March 1918. Article III of the peace treaty provided for Russia’s evacuation of the occupied territory and its return to the Ottoman Empire. The de facto end of occupation had already begun, however, when the Ottoman Third Army in mid-February 1918 crossed the cease-fire line and advanced toward the pre-war border. Trabzon had been recaptured on 24 February, before Brest-Litovsk had even been signed. Erzurum followed in March, with Van and Bayezid retaken by mid-April 1918.

Alexander E. Balistreri, Universität Basel

Section Editor: Pınar Üre

Notes

- ↑ Arutiu͡nia͡n, A.O.: Kavkazskiĭ Front, 1914–1917 [The Caucasus Front, 1914–1917], Yerevan 1971, p. 358.

- ↑ “Beseda predstaviteleĭ pechati s gen. Peshkovym o Turets͡koĭ Armenii” [Interview by representatives of the press with Gen. Peshkov on Turkish Armenia], in: Armia͡nskiĭ Vestnik tn45, 4 December 1916, pp. 8-10.

- ↑ Hovannissian, Richard G.: Armenia on the Road to Independence, 1918. Berkeley 1967, pp. 79-80.

- ↑ Akopia͡n, S.M.: Zapadnaia͡ Armeniia͡ v planakh imperialisticheskikh derzhav v period Pervoĭ Mirovoĭ Voĭny [Western Armenia in the plans of the imperialist powers during the First World War], Yerevan 1967, p. 190.

- ↑ Forestier-Peyrat, Étienne: Faire la révolution dans les confins caucasiens en 1917. La liberté côte cour et côte jardin, in: Vingtième Siècle. Revue d’histoire 135 (2017), pp. 56-72.

Selected Bibliography

- Akarca, Halit Dündar: Imperial formations in occupied lands. The Russian occupation of Ottoman territories during the First World War, thesis, Princeton 2014: Princeton University.

- Akopi︠a︡n, Stepan Mkrtychevich: Zapadnai︠a︡ Armenii︠a︡ v planakh imperialisticheskikh derzhav v period Pervoĭ Mirovoĭ voĭny (Western Armenia in the plans of the imperialist powers during the First World War), Yerevan 1967: Izd-vo Akademii nauk Armi︠a︡nskoĭ SSR.

- Arutiunian, Ashot Osipovich: Kavkazskiĭ front, 1914-1917 gg. (The Caucasus Front, 1914-1917), Yerevan 1971: Aiastan.

- Bakhturina, A. I︠U︡.: Okrainy rossiĭskoĭ imperii. Gosudarstvennoe upravlenie i nat︠s︡ionalʹnai︠a︡ politika v gody Pervoĭ mirovoĭ voĭny, 1914-1917 gg. (Borderlands of the Russian Empire. State administration and nationality politics during the First World War, 1914-1917), Moscow 2004: Rosspėn.

- Holquist, Peter: The politics and practice of the Russian occupation of Armenia, 1915-February 1917, in: Ronald Grigor Suny / Göçek, Fatma Müge / Naimark, Norman M. (eds.): A question of genocide. Armenians and Turks at the end of the Ottoman Empire, New York 2011: Oxford University Press, pp. 151-174.

- Reynolds, Michael A.: Shattering empires. The clash and collapse of the Ottoman and Russian Empires, 1908-1918, Cambridge 2011: Cambridge University Press.