Introduction↑

As a consequence of the First World War, empires in Europe were crushed and new states emerged. It was not surprising that the multinational states of the Habsburg, Russian, and Ottoman Empire came to an end, since nationalism had been a driving phenomenon in each of them throughout the 19th century. What is surprising, however, is the fact that one of the empires' legacies was the emergence of Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia, claiming to be national states while in reality, they were multinational states in which a dominant nation treated the minority population in ways similar to those that had made the majority populations feel mistreated under the Habsburg monarchy.

Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia developed different political and economic structures: As a monarchy, Yugoslavia slid into a dictatorship, while Czechoslovakia remained democratic until the end of the 1930s (the only country in Eastern Europe in the interwar period to do so); Yugoslavia was an agrarian state, Czechoslovakia an industrialized country, in large part due to its Habsburg-heritage. Despite these structural differences, both states were close allies during the interwar period. They formed a network of anti-Habsburg allies, the Little Entente, directing their foreign policy against Hungary. The inner antagonisms of both “Versailles states” became obvious at the latest when Czechoslovakia as well as Yugoslavia were overrun by the direct and indirect domination by Nazi-Germany by the late 1930s.

This article will provide a comparison between the two Habsburg-succeeding states. The tertia comparationis will be the political struggle, the creation of the two countries during the First World War, their formation and proclamation, their legitimating policy and their common foreign policy. These developments will be interconnected with the diplomatic events that occurred at the end of the war, as well as the dissolution of the Habsburg Monarchy in autumn 1918. No special focus will be placed on the military events, disasters, and decisions, although the active use of military force was key in Czechoslovakia and in Yugoslavia to secure the states' respective territorial basis. The story will be told from Czechoslovak and Yugoslav perspectives, with references to the arguments of the victorious powers in Paris; the focus will be on the political events and causalities.

There is no study on the parallel developments of Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia after the First World War. Nevertheless, a comparative analysis of the immediate post-war years in Austria and Hungary will function as a methodological model, since the two countries[1] can be regarded as “counterparts” to Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia: both Austria and Hungary were said to be responsible for the war and were treated as defeated nations in Paris, while Czechoslovakia and Hungary were accepted as partners during the negotiations.

The End of Habsburg in Paris↑

When the Francis Joseph I, Emperor of Austria (1830-1916) died in 1916 after reigning for sixty-eight years, the Habsburg Empire lost not just a symbol, but also a respected father figure who had acted as an important cohesive factor. Two years later, his successor Charles I, Emperor of Austria (1887-1922), who was also the Hungarian King Károly IV, had to face the dissolution of the Empire as a result of military defeat and the growing national antagonisms within the multi-ethnic state. It was not until the war was coming to a close that South Slav and Czech deputies in the Imperial Assembly (Reichsrat) of the Austrian part of the Danube Monarchy began expressing their wish to gain national concessions from Vienna more fervently. In January 1917, the liberation of “the Slavs and of the Serbs” in Austria-Hungary was demanded for the first time. By May 1917, the South Slav and Czech deputies were not pushing for complete independence, but merely for political autonomy within a federal monarchy. US President Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924) projected a post-war peace order in Europe as part of his “Fourteen Points” on 8 January 1918. Point ten of his speech laid out a policy for Austria-Hungary, in which he pleaded for the autonomy of the nations: “The peoples of Austria-Hungary, whose place among the nations we wish to see safeguarded and assured, should be accorded the freest opportunity to autonomous development.” In reaction, Charles conceeded a federal solution for Cisleithania in his “Völkermanifest” on 16 October 1918. This proposal convinced neither the relevant people -those who formed national councils all over the Habsburg Empire and pleaded for political separation- nor Wilson, who had declared in October that he had dropped Point 10 in favor of the full independence of the nations.[2] The collapse of the front in Bulgaria in September 1918 accelerated the end of the Danube Monarchy. As the year was coming to a close, the Danube Monarchy broke up, Charles resigned from his official functions, and finally, on 11 November 1918, he released his subjects from the Oath of Allegiance.

The Paris Peace Conference, where the victorious allies - France, Great Britain, the United States, (the so-called “Big Three”), Italy and Japan - defined the peace conditions for the defeated nations, began January 1919 and lasted until June 1920. It was here that a new “European order” concerning the former empires in Central and East Central Europe was introduced. The “old” Western states themselves were not touched. It was the intention of the victorious states to create nation-states based on the principle of self-determination, and so the emerging new states referred to this right that they had been given (while at the same time refusing it to other, smaller nationalities within their territories).

The negotiations in Paris for each present entity - countries, nations, minorities, and regional delegations - were difficult. General management was in the hands of the United States, France, Great Britain and Italy, the latter of who continuously limited the influence of the small states.[3] Communication took place according to a strict hierarchy, within which the smaller states or ethnicities that were actually affected by the decisions were only allowed to send delegations, and the defeated nations were not even invited to the negotiations, but were only allowed to raise written objections in the final stage of the discussion. Furthermore, general knowledge of the ethnic and political peculiarities of the situation in Eastern Europe was lacking among the representatives of the Big Four. This, of course, caused many misunderstandings, mistakes in translations, failures in numbers, geographical borders, and other important facts.[4] Moreover, the Allies had their own political agenda that shaped the process as well as the results: Great Britain and France, the last remaining big powers in Europe, feared the enlargement of Germany through the annexation (“Anschluss”) of Austria, and the spreading of Bolshevism across Europe. The decisions that affected the situation on the new frontiers, especially that of Czechoslovakia, were motivated by these considerations.

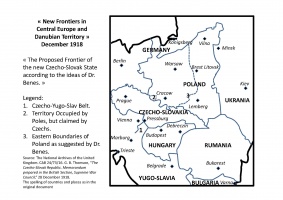

Though the Western powers had not wanted to dissolve Austria-Hungary for much of World War I, it changed in the last year of the war: while the dual monarchy remained a close German ally, the Slavic and Romanian national movements within Austria-Hungary grew stronger with the help of the Allies. In early 1918, acceptance of the destruction of Austria-Hungary and of the establishment of new countries based on the idea of a national principle gained in popularity. In the end, the Habsburg monarchy split into a series of small succeeding states in East Central Europe. With the help of French, British, Italian, and American representatives, the territorial commissions in Paris established frontiers for new and old states from the Habsburg territory: Austria, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, Poland, and Romania.

Delegations from the newly created states Ukraine, Armenia, Lithuania and others parts of the former Russian Empire, as well as delegates from regions such as Bessarabia who were supporting either Romanian or Russian claims over the region, were refused their own official voices at the conference. In Paris, however, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia were given privileged status. In contrast to Austria and Hungary, the Entente (1918) did not regard them as defeated powers. The Paris Peace Conference accepted delegates from both countries, despite the fact that the states were not yet recognized – still, the South Slavic delegation was only accepted under the official name “The Delegation of the Kingdom of Serbia”.[5] Czechoslovak and South Slavic delegates successfully established direct contact with members of the French, British, and American governments and with politically active representatives, such as the British historian Robert Seton-Watson. The delegates found international support in Paris, legitimizing their intentions through agreements with other, culturally similar ethnicities. Since wartime conditions did not allow public votes or any other, similarly anti-Habsburgian declarations within the Danube Monarchy, it was not possible for them to gain a real democratic basis. In the end, they profited from the peace treaties that Austria and Hungary, as well as Germany had no choice but to accept unconditionally. On 28 June 1919, the Treaty of Versailles was signed with Germany; the Treaty of Sèvres with Turkey followed on 10 August 1919, the Treaty of Saint-Germain with Austria on 10 September 1919, the Treaty of Neuilly-sur-Seine with Bulgaria on 27 November 1919, and finally the Treaty of Trianon with Hungary on 4 June 1920. Each of these documents meant the loss of territories for the signatories, armament limitations and obligations to pay reparations.

The Republic of Czechoslovakia↑

War Time Activities↑

Until World War I, Czech political parties imagined autonomy within a federalized monarchy as the national political system. During the war, this concept evolved into the postulation of an independent state. Especially Czech exile politicians Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk (1850-1937) and Edvard Beneš (1884-1948) and Slovak Milan Štefánik (1880-1919), the leaders of the Czech National Council in Paris (founded in 1916, and to be renamed “Czechoslovak National Council”), continued to negotiate with the Entente during the last months of the war. In May 1918, Italian politicians, followed by the French government a month later, recognized the Czechoslovak National Council as representing the Czechs and Slovaks; in September 1918, the US government followed. In August 1918, the Foreign Office had allowed the National Council to participate in the Paris Peace Conference and was promised by the Entente that the unification of a Czech and Slovak state would be supported; Czechoslovakia had not yet been proclaimed. On 14 October, the Czechoslovak national committee in Paris declared a provisional government with Masaryk as president and Edvard Beneš as foreign minister. It was formally recognized by France, Russia, the United States, Italy and Great Britain within a few days.

In order to gain as much support as possible from Czechs and Slovaks, Masaryk and Beneš propagated their ideas among emigrant groups, while they were prohibited from agitating among Czechs and Slovaks in the Habsburg Empire. Already in the early years of the war, Czech and Slovak emigrants in the United States had passed common agreements on a future political design. At a conference on 22 and 23 October 1915, the Slovak League of America - the umbrella organization for the Slovaks in the US - and the Czech National Association in Cleveland signed the Cleveland Agreement over a common state with far reaching Slovak autonomy. In Pittsburgh, where many Slovak emigrants lived, Masaryk met with the Slovak League of America, the Czech National Association, and the Union of Czech Catholics. In the Pittsburgh Agreement (30-31 May 1918) they reassured the Slovaks that in a common state of Czechs and Slovaks (“Czecho-Slovakia”), the Slovaks would have autonomy and their own assembly. The Washington Czechoslovak Declaration of Independence followed on 18 October 1918, but made no mention of Slovak autonomy. At the end of the war, these documents became important; during the Paris meetings, the main Allied powers discussed new borders within the Habsburg territories. More often than not, however, the people within the future states did not know about the arrangements before the end of the war.

A new National Council (Národní Výbor) was founded in Prague on 13 July 1918 and became the driving institution facilitating a peaceful transfer of political power. Before World War I, it was headed by the popular Czech politician Karel Kramář (1860-1937), who took a rather russophile standpoint and was tried by an Austrian-Hungarian military court for his political conviction. The thirty members of the National Council were provided by political parties, in accordance with the results of the parliamentary elections from 1911. The Czechs declined the offer to gain political autonomy; they objected to Emperor Charles’s attempt to mediate and dismissed his manifesto to the “Austrian peoples”. Together with some other members of the National Council, Kramář travelled to Geneva to meet with Beneš and discuss how to fix the conditions in order to take over political power in Prague. Meanwhile, in the Czech capital on 28 October 1918, the existence of the sovereign Czecho-Slovak national state was declared, made manifest in a law on the creation of the state that had not been averted by the Austrian military administration. At the same time, military troops were being formed, and the Czech units of the Austrian-Hungarian army were concentrated in Prague. Later on, they would be united with the Czechoslovak military units that had been formed by exile politicians in France, Italy, and Russia (an army of circa 250,000 soldiers) to fight for the cause of the Entente. Their aim was to support the establishment of independent statehood. The most famous arena of the Czechoslovak legion was the Russian Civil War on the side of the anti-Bolshevik forces, until those forces left Russia in 1920.[6]

Slovak politicians acted much more reluctantly during the war and were hesitant to demand political rights within the Hungarian part of the Habsburg monarchy. They were not as active as the Czech representatives at pushing for a Slovak program – and in fact, no program existed except for the Cleveland Agreement and the Pittsburgh Agreement. Consequently, the Western powers knew next to nothing about the Slovak issue, which for them appeared to be nothing more than a part of Hungary, and therefore a war enemy. On 19 October 1918, the member Ferdinand Juriga (1874-1950) announced the foundation of a Slovak national council in front of the Budapest Diet. When this council, consisting of representatives from all over Slovakia, met in the city of Turčiansky Svätý Martin on 30 October 1918, they hinted at the common cultural ties among the countries of the “Czecho-Slovak nation” and declared themselves to be the only authority with the right to speak for the “Slovak branch”, but they did not separate from the Kingdom of Hungary under constitutional law. While the Martin Declaration endorsed this sense of common Czech and Slovak statehood, the Slovak representatives did not know that the Czechoslovak Republic had already been proclaimed in Prague on 28 October 1918. This was the result of not only a more or less passive attitude of Slovak politicians who did not appear as active participants of the political processes in the formation of a Czechoslovak state, but it was also facilitated by the military situation in Slovakia and the pressure this put on the Slovak representatives. In November, Hungarian troops occupied Turčiansky. Svätý Martin and the president of the Slovak national council, Matus Dula, was arrested.

The New State↑

The creation of the new state was finalized on 14 November 1918 in the first session of the provisional national assembly in Prague, consisting exclusively of Czechs (mirroring the results of the 1911 election for the Austrian Reichsrat) and of Slovaks; other nationalities were not admitted.[7] The provisional Prime Minister Kramař declared the dismissal of the House of Habsburg and proclaimed the Czechoslovak state as a republic. The official name of the country between 1918 and 1938 was “Czechoslovak Republic”, comprising the former Austrian territories of Bohemia, Moravia, and Czech Silesia, as well as the former Hungarian territories of Slovakia and Carpathian Ruthenia -both without any historical-constitutional connection to the Czech territories. Masaryk was elected President by acclamation. At the same time, the first cabinet was nominated with sixteen ministers, among them Beneš as foreign minister and Štefánik as minister of war. After a four-year exile, Masaryk returned to Prague on 21 December 1918 and was received with enthusiasm. In that moment, the joy over the newly founded state outweighed the concerns over the problems at hand, including the revisionism of the neighbouring states, unresolved social problems and ethnic tensions, and the persistent military quarrels. After Béla Kún’s (1886-1938) Bolshevik troops had invaded East Slovak territories from Hungary, a short-lived Soviet Republic in Eastern Slovakia increased the levels of unrest from 16 June to 7 July 1919. It was not until they had been successfully driven out by the Czechoslovak army that Slovakia became fully incorporated into the new state.

It was a longwinded process to gain control over Transcarpathia (today Zakarpatska Ukrajina, a part of Ukraine) with its multi-ethnic population, consisting of Rusyns (Ukrainians), Germans, Slovaks, Rumanians, Jews, Magyars, and others. In the spring of 1919, Czechoslovak and Romanian troops defeated Communist military forces from Hungary. On 8 May 1919, and in light of these difficult conditions, the Central Ruthenian National Council, backed by the exile Council in the United States, declared that Czechoslovakia could annex Uzhhorod if the latter gained her autonomy.[8] As the Ukraine was still quite unstable, the region was incorporated into Czechoslovakia in the summer of 1919. Thus, Czechoslovakia gained a common frontier with her ally Romania.

Czech troops also pursued their goals in the mostly German-inhabited frontier regions on the Czech borders. Germans from Bohemia had organized themselves into a committee made up of all German parties from the parliament in Bohemia and Moravia, and established the German Province of Bohemia. Referring to Wilson’s Fourteen Points on 13 November 1918, they demanded that their territories should remain a part of the Austrian state. Czech military forces put an violent end to their attempts to join Austria by occupying the German inhabited regions, and killing fifty-four und wounding eighty-four peaceful German protesters in March 1919.[9]

On 29 February 1920, the national assembly in Prague ratified the constitution of Czechoslovakia, declaring the Czechoslovak Republic which was to be headed by a president who was to be elected by the national assembly for a seven-year term. It was not in the Slovaks’ interest that the administration was centralized instead of federal and that the constitution did not provide autonomy for the Slovaks. And while Slovak concepts of the new state continued to use the hyphenated spelling “Czecho-Slovakia” (including in the peace treaties), “Czechoslovakia” soon became the common spelling in Prague.

Despite the consequences of the war, the new Czechoslovak state started from an economic level comparable to Western Europe. It had one-quarter of the population of the Habsburg Empire, one-fifth of its territory, and two-thirds of its industries: 56 percent of the total Austrian industry had been located in Czech territory, while 64 percent of iron-steal and coal mining production, 60 percent of textiles, and 90 percent of the Habsburg sugar production was to be found in Bohemia and Moravia.[10] In comparison to the other states in Eastern Europe during the interwar period, Czechoslovakia was an exception to the political rule. While all the neighbouring countries slipped into autocratic systems as their rulers claimed total power for themselves, Czechoslovakia remained democratic and a more or less stable state until it was dismembered in 1938-1939. Despite the democratic system, two informal structures were very influential on actual policy: a circle of politicians around Masaryk, the so-called “hrad” (“the castle”), and the representatives within the five most important Czech parties, the “pětka” (“the Five”). It was common for their decisions to pass in parliament without any debate.

Czechoslovakism: Supranational Ideology and the Ethnic Issue↑

The First Czechoslovac Republic was a multi-ethnic country. According to the first census in 1921, in which each respondent had to declare their nationality, the results were as follows:

| Nationalities | Absolute Numbers | Percentages |

| Czechs | 6,843.343 | 50,2 % |

| Slovaks | 1,976.320 | 14,6 % |

| Germans | 3,218,005 | 23,6 % |

| Hungarians | 761.823 | 5,6 % |

| Ukrainians/Ruthenians/Russians | 477.430 | 3,5 % |

| Jews | 190.857 | 1,4 % |

| Poles | 110.138 | 0,8 % |

| Others | 35.257 | 0,3 % |

| Total | 13.613.172 | 100 % |

| among them foreigners | 238.808 | 1,7 % |

Table 1: Nationalities within Czechoslovakia (15 February 1921)[11]

Germans, Hungarians, Poles, and Ruthenians constituted one-third of the inhabitants as national minorities; the Germans, the second largest group of people, outnumbered the Slovaks. With the aim to achieve a majority of Slavs thus legitimate the proclamation of Czechoslovakia as a nation-state based on the principle of national self-determination, the artificial “Czechoslovak” nationality was introduced.[12] “Czechoslovakism” comprised the Czech and the Slovak peoples and was rooted in 19th century nationalism among Czechs who strived for the strengthening of national Czech aspirations, as well as among (mostly Protestant) Slovaks who opposed magyarization (the transformation into Hungarians). Czechoslovakism as a political concept was revived by Masaryk and Beneš during World War I. They declared that Czechs and Slovaks constituted two branches of one nation, the “Czechoslovaks”, who had been separated under Austro-Hungarian imperialism and especially by Hungarian assimilationism. Democratic Czechoslovakism was the political consensus among leading political parties in Prague during the interwar period; another important transmitter of Czechoslovakism was the president of the state.

Czechoslovakism was to unite two culturally unlike nations that were at different stages of development, since Czechs and Slovaks had belonged to different parts of the Habsburg Monarchy. While the Czechs had lived mostly in an economically highly developed area that was subordinated directly to Vienna, the Slovaks had been exposed to Hungarian domination, had had limited possibilities to formulate a national concept and sense of self, and suffered from underdeveloped economic infrastructure. In order to balance out the religious differences, Czechoslovakism appealed to Hussitism, Protestantism, and secularism, which was a point of contention for the largely Catholic Slovaks. “Czechoslovak” was designated the state language with a privileged status. The idea behind this was that there was one Czechoslovak language in two versions already, though Czech and Slovak obviously differed as standard languages.

Czechoslovakism was not an answer to the national question; rather, it was a problem in itself. National antagonisms already began to develop in the early stages of the Czechoslovak statehood, resulting first and foremost in the centralized conception of the state. Czechoslovakia, however, certainly did not turn into a second Switzerland, a federal state for the different nationalities with equal rights, as Beneš had once proclaimed in front of the New States Commission at the Paris Peace Conference.[13] For Czechs, it was difficult to accept Slovaks as equal to them, since even Masaryk had declared in 1921: “There is no Slovak nation; that’s an invention of Hungarian propaganda.”[14] This cultural disadvantage notwithstanding, those Slovaks who believed in the idea of a common Czechoslovak statehood were involved in leading a political everyday life to a certain degree. In every government, two or three Slovak ministers were present, and fourteen Slovaks held various government positions.[15] But they were not represented according to the census in offices such as the ministries and departments.[16] While it was not possible to instil a genuine Czechoslovak conviction within the Czechs and Slovaks by means of propaganda, educational measures among the Slovaks led to a long-term change in national consciousness. Thus, the founding of Comenius University in the new Slovak capital Bratislava in 1919 resulted in generating a new generation of Slovak intellectuals and a Slovak political elite, taught by a body of professors, most of who were of Czech heritage.[17] At the same time, Slovakia profited from political modernisation and participation, as well as from new measures that were introduced, including social rights for workers.

The situation for nationalities with minority status was different. Although Czechoslovakia had signed a treaty in Paris which ensured minority rights, the German and Hungarian parts of the population strongly opposed the new state.[18] Along with some other minorities, they were excluded from the national ideology of Czechoslovakism, and had not been allowed to be present in the Czechoslovak national assembly, but participated in elections and in government coalitions after 1926.

The Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes↑

National Interest Groups during the War and the Creation of the South Slav State↑

As was the case in Czechoslovakia, elites both in- and outside of the country pushed for the creation of a Yugoslav state. One of the driving forces was the ruling Serbian dynasty Karadjordjević, who had expelled the pro-Habsburg dynasty Obrenović in 1903. Exhausted from the Balkan Wars of 1912-13 (during which Serbia had doubled its territory, no less), Serbia became involved in World War I. When the Serb nationalist Gavrilo Princip (1894-1918) shot the Austrian successor to the throne Franz Ferdinand, Archduke of Austria-Este (1863-1914), and his wife in Sarajevo, in response to which Austria-Hungary declared war on Belgrade later on, the Serbs were not prepared for a war militarily. Despite of this shortcoming, it took the Austrian troops until December 1915 to occupy Serbia, after which the remaining parts of the Serb army as well as the government were transferred to Corfu. In early 1916, Montenegro and Albania were occupied by the Central Powers. During the war, it was a tragic fact that Serbs living in the Habsburg monarchy fought against Serbs from Serbia.

During the evacuation to Corfu Island, the Serb government repeatedly announced the intention to “liberate and unite all unfree brothers, Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes”. In a letter to the Entente on 4 September 1914, the Serb government declared that it wanted to establish a “Slav state,” in which all Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes from Serbia, Bosnia, Herzegovina, Vojvodina, Dalmatia, Croatia, Istria, and Slovenia were to be united. This state was planned as a warrantor of peace in the Balkans. Analyses that were being conducted by Serb and other geographers, historians, and statisticians around the same time show that the South Slavs formed one single nation that simply existed under several names. These findings were handed over to representatives of the Entente to convince them to support the project of a common South Slav state.

Meanwhile, in London in 1915, South Slav émigrés from Austria-Hungary had founded the Yugoslav Committee as a political platform. The members of the committee were mostly Croats, among them Frano Supilo (1870-1917), Ante Trumbić (1864-1938), and the famous sculptor and architect Ivan Meštrović (1883-1962). Their aim was to propagate the idea of a union that brought together all South Slavs in one country on an international level.[19] They established contacts with the Serb government, still on the island of Corfu at the time. The most important result of these talks was the Corfu Declaration, signed in 1917. It was a compromise, advocating a parliamentary monarchy. The signatories agreed on the creation of a common state for the South Slav “people with three names” under the reign of the Serb dynasty Karadjordjević. The state territory was to comprise the frontiers of closed settlement areas, based on the right to self-determination. A constitution was to be promulgated by a “numerically qualifiable majority” in a constituent assembly. While it was problematic that the wording was rather unclear, it was worse that the most important question was left untouched: namely, the political structure of the new state. Different concepts were discussed. The chairman of the committee, Trumbić, favored a federal state that would comprise all South Slavs of the Danube Monarchy. In contrast, the resolute Serb Prime Minister Nikola Pašić (1845-1926) advocated centralism, as he detected the chance for Serbia to expand its territory greatly in the projected state. In his eyes, the structure of the projected state should not differ from the structure of the Serb kingdom. These contradictory positions mirrored the situation between Czechs and Slovaks, and with similar subsequent problems. The political visions were put into reality when the Bulgarian front collapsed in September 1918, the Serb army reoccupied Serbia, and the Serb government continued its activities in Belgrade.

The South Slav National Committees↑

During the war, national committees consisting of representatives in the Reichsrat were formed by the majority of the nationalities in South Slav areas who acted as provisional executive bodies. In the northern parts, the Slovene and Croat politicians also pleaded for a South Slav solution. Committees were founded in August 1918 in Slovenia, and on 20 September in Bosnia. On 5 and 6 October 1918 in Zagreb, the National Council of the Slovenes, Croats and Serbs was formed by delegates of the Croat, Serb, and Slovene parties to propagate the political claims in the name of the South Slav peoples within the Danube Monarchy. They published a program in which they advocated the idea to unite all South Slavs within a “free and independent state”. In answer to Emperor Charles I’s “Völkermanifest” from 18 October 1918, the National Council demanded a “uniform, independent South Slav national state in all territories where Slovenes, Croats and Serbs lived, regardless of the frontiers of countries and provinces”.

One committee after another declared that they would separate themselves from the Habsburg monarchy. On 30 October, the Bosnian national committee expressed its will to unite with Serbia, while the military situation for Slovenia and Croatia became more and more desperate. With the retreat of the dissolving Austrian-Hungarian army, Italian troops threatened Croat territories, occupied Rijeka/Fiume and approached Ljubljana, with Croat and Slovene troops not able to stop them. With the military pressure and general riots, the National Council in Zagreb pleaded for the help of the Serbian army and proclaimed the immediate unification of Croatia with the kingdoms of Serbia and of Montenegro on 24 November.[20] A violent protest against this decision in Zagreb on 5 December 1918 showed that this was not unanimously accepted by the Croats,[21] while in Vojvodina, some nationalities agreed to unite with Serbia. On 25 November 1918, the 757 deputies of the National Convention of Bačka, Banat, and Baranya decided to separate themselves from Hungary, as the Serb, Croat, Slovak, Rumanian, and Bunjevac minorities who had suffered from the policy of magyarisation, approved the unification with the kingdom of Serbia. One day before this decision was made, Syrmia, which had been a part of Croatia-Slavonia with 75 percent Serbian population until then, had also agreed to unification.

During the war and throughout the occupation of Montenegro by Austrian-Hungarian troops, Nikola I, King of Montenegro (1841-1921) went into (and remained in) exile and was replaced by a national assembly on 26 November 1918 in Podgorica. The same assembly decided to unite Montenegro and the “brotherly Serbia” in a common state under the Serbian dynasty Karadjordjević. The assembly, not recognized by a single one of the Great Powers, put an end to Montenegrin statehood and cleared the way for usurpation into the South Slav state.

The Proclamation of the South Slav Kingdom↑

Prince Regent Alexander I Karadjordjević (1888-1934), who succeeded to the thrown in 1921, proclaimed the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, or S.H.S. Kingdom, in Belgrade on 1 December 1918. He declared the unification of the Kingdom of Serbia with the other territories inhabited by Slovenes, Croats and Serbs, underlining what the “best sons of our blood, of all three religions, of all three names on both sides of the Danube, the Sava and the Drina” had fought for decades.[22] That Belgrade was at the heart of the new kingdom was justified by the fact that the Serbs had suffered from immense war losses: about 1.2 million people had died as a result of direct or indirect consequences of war. This was nearly one quarter of the pre-war Serb population, and the highest percentage of victims in all countries that had been involved. Moreover, the common notion was that Serbia had “sacrificed” her own kingdom for the new state.

The S.H.S. Kingdom was a collage of political legacies and consisted of territories with various cultures, political pasts, religions, and traditions: Serbia and Montenegro had been ruled by two dynasties at the beginning of the 20th century – the Karadjordjevići and the Njegoši – and had been part of or related to the Ottoman Empire. Croatia, Slovenia, and Dalmatia had been integrated into the Danube Monarchy. Bosnia had been incorporated into the Ottoman Empire, until being occupied by Austria-Hungary after the Congress of Berlin in 1878, and annexed in 1908. The existence of the newly created South Slav state was in accordance with the professed determination of the United States, Great Britain and France. Great Britain, above all, did not lose her geostrategic interest in Yugoslavia over the course of the 20th century.[23]

In Paris, the South Slav kingdom was treated as a winner state, since Serbia had adopted the position of the Entente, while Croats and Slovenes had been on the side of the Habsburg monarchy. The South Slav delegation decidedly represented the national issue,[24] and although its demands were not modest, the territory ceded to the kingdom in the end exceeded the regions where South Slavs were the majority. The new South Slav frontiers were fixed in the treaties between the victorious states and Austria (in Saint-Germain on 10 September 1919), with Hungary (on 4 June 1920 in Trianon) and with Bulgaria (in Neuilly on 27 November 1919). Eventually, the S.H.S. Kingdom, measuring nearly 250,000 square kilometres, became the biggest country in the Balkans. The first constitution, promulgated on 28 June 1921, the famous Vidov-dan (St. Vitus day), declared the country a parliamentary monarchy. One of the most difficult structural tasks was its multi-ethnic population.

Yugoslavism: the Supra-National Ideology and the National Issue↑

The first South Slav census conducted in 1921 registered about 12 million inhabitants.[25] The population by nationality was registered as follows:

| Nationalities | Absolute Numbers | Percentages |

| „Serbo-Croats“ | 8.911.509 | 74,36% |

| Slovenes | 1.019.997 | 8,51% |

| Germans | 505.790 | 4,22% |

| Magyars | 467.658 | 3,90% |

| Albanians | 439.657 | 3,67% |

| Romanians | 231.068 | 2,03% |

| Turks | 150.322 | 1,26% |

| Czechs and Slovaks | 115.532 | 0,96% |

| Ukrainians | 25.615 | 0,21% |

| Russians | 20.568 | 0,17,% |

| Italians | 12.553 | 0,11% |

| Others | 69.878 | 0,6% |

| Total | 11.984.911 | 100% |

Table 2: Results of the 1921 Census[26]

Regarding its ethnic composition, the S.H.S. Kingdom was a multinational state with a majority of Slavs, but also Muslims in Bosnia and Sančak, Albanians in Serbia, Magyars and Romanians in the Vojvodina, Germans in both the Vojvodina and Slovenia, and Italians mostly on the Dalmatian coast. Yugoslavia considered herself a “national state” with one dominating nation, the “South Slav nation with three names”, although no single nationality had an absolute majority. To enhance the number of the Serb population, Montenegrins and Macedonians were added, as well as Bosnians.[27] Yet the percentage of Serbs did not reach 50 percent. Only Serbs, Croatians, and Slovenes were regarded as “state-making” (državotvorni; in the sense of state nations; this was similar to the Czech and Slovak case).

In ways similar to Czechoslovakia, the political idea to integrate as many nationalities as possible and create a (seemingly) homogeneous population in Yugoslavia was the propagation of a super-national ideology, of “Yugoslavism”. This movement had started in the 19th century among Serbs, Slovenes, and Croats. It was popular since it highlighted the equality of all South Slav peoples. However, the way in which it was implemented in the S.H.S. Kingdom did not follow this line. In reality, the new (and old) political center was Belgrade, and the Serbian dynasty and Serbs became overly represented in official life. They dominated the government, the diplomatic corps, the police, and the army (in 1931, only one general in the Yugoslav army was not a Serb). Non-Yugoslav minorities were excluded from the state apparatus; even on the local level, their ability to participate was reduced.[28]

One problem was the definition of the official language, as only Serb and Croatian could be amalgamated into Serbo-Croatian without distorting grammar and other linguistic rules too much. It was quite a stretch to include Slovenian, a language that had generated completely different lexis and other linguistic peculiarities. To keep the idea of a common language, however, the first constitution of 1921 declared “Serbo-Croatian-Slovene” the “common official language”. Thus, linguistic, as well as religious, cultural and other differences between the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes were seen as unimportant matters in the attempt to forge a single Yugoslav nation by political and cultural means.[29]

During the interwar period, it was not possible to govern effectively within Yugoslavia. Political parties with different ethnic background (only the Communist party represented an over-national party) blocked each other, the tensions between the new peripheries in the North (Slovenia and Croatia) and Belgrade grew, and political terrorism including assassinations and bombings characterized the political atmosphere. In 1929, Alexander I, King of Yugoslavia (1888-1934) created an absolute dictatorship as the last means to reach political unity in newly-named “Kingdom Yugoslavia” (Kraljevina Jugoslavija). It strengthened centralism, with one of the first measures of the King’s dictatorship being the 1929-promulgation of the law on the administrative reorganization which ignored historical boundaries. In 1934, King Aleksandar I was assassinated by a Bulgarian terrorist.

In the end, the identification with Yugoslavia was low among Slovenes, Croats and the minorities in the country. The chance to achieve political equilibrium with the Croats by way of the compromise of the “Sporazum” in August 1939 failed since there was not enough time for it to develop positive results, as Yugoslavia soon became involved in the beginning of the Second World War.

The First Yugoslavia and the First Czechoslovakia as Political Allies↑

It is no surprise that the South Slav Kingdom and Czechoslovakia became close allies during the interwar period. Politicians from both countries had already established ties on the eve of the First World War, when Masaryk in Belgrade improved the contacts to the Serb government, and Karel Kramář had visited Belgrade several times to find allies for the Pan-Slav course he was pursuing.[30] After World War I, Czechoslovakia and the S.H.S. Kingdom were closely connected through their embassies in the capitals, as well as by Czech consulates in Ljubljana, Zagreb, Sarajevo, Skopje, and in Split (until 1929), and by Yugoslav consulates in Brno and (since 1930) in Ostrav.[31] From their shared anti-Habsburgian position, both countries developed their own specific concepts for foreign policy. Their biggest fear was for Habsburg to be restored, but they were also opposed to Hungary, which had lost huge territories. Another rising opponent was fascist Italy, which was trying to expand in the Balkans. From the beginning, Prague and Belgrade understood that not only the Allies had to be treated as diplomatic partners, but also the other little states in Eastern Europe. And soon enough, they had orchestrated diplomatic connections in South East Europe to prevent being endangered by the losers of the First World War. As early as 1919, Beneš offered the South Slav government a defensive treaty against Hungary, calling upon Romania to join in 1920. Three bilateral treaties were closed: Belgrade and Prague signed a treaty on 14 August 1920, and Romania followed in 1921 as a full member of the defensive alliance. Mocked by the Hungarian press as “Little Entente”, this military alliance was directed against a possibly reemerging Habsburg monarchy and against Hungary, which was regarded as a revanchist country. The Little Entente became a part of the French security system in Eastern Europe after Czechoslovakia signed a treaty with Paris in 1924, with Romania in 1926, and in 1927 with the South Slav Kingdom. France supported the Little Entente as a substitute for its former strong connection to the Russian Empire, as the Little Entente opposed changes in the military provisions of the Paris treaties and objected to territorial revisions in Europe.[32]

When the last Habsburg Emperor Charles I of Austria tried to regain his throne in Hungary twice (in April 1921 peacefully, in October 1921 with military means), he failed because of the mobilization of Czechoslovakia and the South Slav Kingdom. After these incidents, the Hungarian diet declared that Charles and his dynasty had lost all rights related to the crown in Hungary, and Charles died in exile on Madeira soon after. The Little Entente endorsed the member states in their diplomatic contacts in regular conferences after 1922. But it was neither able to establish an economic union, nor was it flexible enough to overcome the opposition from the First World War, and, finally, it was not able to respond to the rising German expansion, instead increasing the antagonisms between the victorious and the defeated states of 1918.[33]

When Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) came to power in Germany in 1933, the situation for Czechoslovakia worsened dramatically, as he vigorously pushed to revise the Versailles Treaty. This development showed the weakness of the security system in East Central Europe; in August 1938, during the last meeting of the Little Entente, Czechoslovakia tried and failed to gain support from Yugoslavia and Romania against the German aspirations. When the Munich Agreement was signed by Hitler and the Western powers in September 1938, and the border regions of Czechoslovakia, inhabited mostly by Germans, were ceded to Germany, it marked the end of the Little Entente, as well as the beginning of the end of the First Czechoslovak Republic. Similar to Czechoslovakia during World War II, Yugoslavia was dismembered in April 1941, after the German Wehrmacht and her allies attacked.

Conclusion↑

Both Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia were created by the Versailles system, founded by the determination of their leading politicians, the national movements of the dominant “state” peoples, and Great Britain, France, and the United States in Paris. An elite of representatives had fulfilled their self-assigned roles to negotiate the establishment of new states to succeed the Habsburg regions. The establishment of a territorial basis succeeded in both cases, in part due to the military forces, and mainly the Serbian army and the Czech troops within the former Habsburg army, together with the Czechoslovak legion formed in exile.

The path to establish new political forms was different: Czechoslovakia became a republic, Yugoslavia stayed a monarchy. To create legitimacy for the Slav peoples, both countries conducted a form of nation-building that favored the dominating nations, the Czechs and the Serbs, by creating a “Serbocroatian” and a “Czechoslovakian” nation. Thus, “Yugoslavism” as well as “Czechoslovakism,” albeit a 19th century concept, helped to constitute and legitimize the state after the First World War. It was difficult to push for collective rights for Germans and other minorities.

Both countries held different international standings within the “new Europe”: Czechoslovakia succeeded in gaining a positive image for its social policy, its political stability, and for having Masaryk the “philosopher” in political office. This may have been the reason why the Western countries did not focus on democratic dysfunctions too much. Yugoslavia, however, was never regarded as stable, since political repression and murder were an everyday-reality. In the end, neither Prague nor Belgrade could handle the above mentioned domestic difficulties rooted in the legacies of the First World War in either political system: Yugoslavia as an authoritarian monarchy since 1929, and Czechoslovakia as a republic.

For both countries, the Habsburg-factor was a constant menace throughout the interwar period. What united the new states in East Central Europe was their insistence on upholding the status quo in Europe and their anti-Habsburgian sentiments that did not allow for any reconciliation or collaboration with the defeated states of World War I. Their justified fear of a Habsburg restoration made them, unite, alongside Romania, within the Little Entente, a part of the French security system in Central Eastern Europe aimed at maintaining the political and territorial status quo in Europe.

From the perspective of the non-dominant nations, the concept of Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia as nation states was a mistake from the beginning; both modeled their political systems on that of the French Republic, but could not serve for a multi-national state. The way that Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia interpreted the concept of a “nation-state” on the basis of the Paris Peace Treaties of 1919 provoked many disturbances, as inequalities and discontent among those ethnicities that did not participate in the implementation of this concept peaked.[34] Ultimately though, it was the weaknesses of the postwar order that led to the next world cataclysm with the World War II. Despite this, Czechoslovakia as well as Yugoslavia were given a second chance after World War II, this time under Soviet and socialist auspices. This, too, proved to be only a temporary “break” before national ambitions exploded again within Yugoslavia during the 1990s, and imploded within the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic, in the scope of which Trianon and Neuilly were revised one final time.-

Katrin Boeckh, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München/IOS Regensburg

Section Editor: Holger Afflerbach

Notes

- ↑ See: Swanson, John: The Remnants of the Habsburg Monarchy: The Shaping of Modern Austria and Hungary, 1918-1922, New York 2001.

- ↑ von Reiswitz, Johann Albrecht: Die politische Entwicklung Jugoslawiens zwischen den Weltkriegen, in: Markert, Werner (ed.): Osteuropa-Handbuch. Jugoslawien, Köln, Graz 1954, p. 70.

- ↑ Sharp, Alan: The Versailles Settlement. Peacemaking in Paris 1919, New York 1991, p. 24.

- ↑ See, e.g. Suveică, Svetlana: "Russkoe Delo" and the "Bessarabian Cause": The Russian Political Émigrés and the Bessarabians in Paris (1919–1920), IOS-Mitteilungen Nr. 64 (Februar 2014), p. 27, 33.

- ↑ Mitrović, Andrej: The Yugoslav Question, the First World War and the Peace Conference, 1914-20, in: Djokić, Dejan (ed.): Yugoslavism. Histories of a Failed Idea 1918-1992, London 2003, pp. 42-56, p. 45.

- ↑ McGuire Mohr, Joan: The Czech and Slovak Legion in Siberia 1917–1922, Jefferson/London 2012.

- ↑ Hoensch, Geschichte der Tschechoslowakei, p. 28.

- ↑ Magocsi, Paul : A History of Ukraine. Third Edition, Seattle 1998, pp. 518-519.

- ↑ Kalvoda, The Genesis of Czechoslovakia, p. 448; Suppan, Arnold: Austrians, Czechs, and Sudeten Germans as a Community of Conflict in the Twentieth Century. CAS Working Papers in Austrian Studies Working Paper 06-1 (October 2006), p. 9.

- ↑ Berend, Ivan: Decades of Crisis. Central and Eastern Europe before World War II, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London 1998, p. 21.

- ↑ Bohmann, Alfred: Menschen und Grenzen. Bevölkerung und Nationalitäten in der Tschechoslowakei. Volume 4, Cologne 1975, p. 96.

- ↑ Bakke, Elisabeth: The Making of Czechoslovakism in the First Czechoslovak Republic, in: Schulze Wessel, Martin (ed.): Loyalitäten in der Tschechoslowakischen Republik 1918-1938. Politische, nationale und kulturelle Zugehörigkeiten, Munich 2004, pp. 23-44.

- ↑ Kalvoda, The Genesis of Czechoslovakia, p. 445.

- ↑ Mahoney, William: The History of the Czech Republic and Slovakia, Santa Barbara, Denver, Oxford, p. 150.

- ↑ Kirschbaum, A History of Slovakia, p. 172.

- ↑ In 1938, only 131 out of 7,470 civil servants were Slovaks, and only one Slovak had the position of a general in the Czechoslovak army. See Ibid., p. 175.

- ↑ Lemberg, Hans: Der Versuch der Herstellung synthetischer Nationen im östlichen Europa im Lichte des Theorems vom nation building, in: Schmidt-Hartmann, Eva (ed.): Formen des nationalen Bewußtseins im Lichte zeitgenössischer Nationalismustheorien, Munich 1994, pp. 145-161, p.151; Kirschbaum, A History of Slovakia, p. 174.

- ↑ Merriwether Wingfield, Nancy: Minority Politics in a Multinational State. The German Social Democrats in Czechoslovakia 1918-1938, Boulder 1989.

- ↑ Robinson, Connie: Yugoslavism in the Early Twentieth Century. The Politics of the Yugoslav Committee, in: Djokić , Dejan and Ker-Lindsay, James (eds.): New Perspectives on Yugoslavia. Key Issues and Controversies, London, New York 2011, pp. 10-26.

- ↑ Banac, The National Question in Yugoslavia, pp. 127-136; Pavlowitch, Kosta: The First World War and the Unification of Yugoslavia, in: Djokić, Dejan (ed.): Yugoslavism. Histories of a Failed Idea 1918-1992, London 2003, pp. 27-41, here pp. 39-41.

- ↑ Matković, Stjepan: Istraživačke dopune o pobuni 5. prosinca 1918. godine [Research Supplements to the Mutiny of 5th December 1918], in: Matijecić, Zlatko (ed.): Godina 1918. Prethodnice, zbivanja, posljedice. Zbornik radova s međunarodnoga znanstvenog skupa održanog u Zagrebu 4. i 5. prosinca 2008 [The Year 1918. Proceedings, Events, Consequences. Anthology of Works from an International Scientific Meeting in Zagreb on 4 and 5 of December 2008], Zagreb 2010, pp. 129-153.

- ↑ Boeckh, Katrin: Serbien. Montenegro. Geschichte und Gegenwart. Regensburg 2009, 99-100.

- ↑ Evans, James: Great Britain and the Creation of Yugoslavia. Negotiating Balkan Nationality and Identity, London 2008; Lane, Ann: Britain, the Cold War and Yugoslav Unity 1941-1949, Portland, Toronto 2012.

- ↑ Lederer, Ivo: Yugoslavia at the Paris Peace Conference. A Study in Frontiermaking, New Haven, London 1963.

- ↑ The Yugoslav population increased to 14 million in 1931. The results of the 1931-census, however, were published as late as 1943 by the German occupiers, since Belgrade was not interested in showing the inhomogeneity of the population.

- ↑ Wolfrum, Gerhart: Die Völker und Nationalitäten, in: Markert, Werner (ed.): Osteuropa-Handbuch. Jugoslawien, Köln, Graz 1954, pp. 14-36, p. 16.

- ↑ Only in Socialist Yugoslavia, a Bosnian/Macedonian (respectively) nationality was officially recognized.

- ↑ Janjetović, Zoran: Deca careva, pastorčad kraljeva. Nacionalne manjine u Jugoslaviji 1918-1941 [Emperors’ Children, King’s Stepchildren. National Minorities in Yugoslavia 1918-1941], Belgrade 2005.

- ↑ Wachtel, Andrew: Making a Nation, Breaking a Nation. Literature and Cultural Politics in Yugoslavia, Stanford, California 1998, p. 69.

- ↑ Chrobák,Tomáš and Hrabcová, Jana: Česko-srbské vztahy [Czech-Serb Relations], in: Hladký, Ladislav (ed.): Vztahy Čechů s národy a zeměmi jihovýchodní Evropy [Relations of the Czechs with the Peoples and Countries of Southeastern Europe], Prague 2010, pp. 97-119.

- ↑ Chrobák,Tomáš, Hrabcová, Jana and Teichmann, Miroslav: Československo-jugoslávské vztahy [Czechoslovak-Southslav Relations], in: Hladký, Ladislav (ed.): Vztahy Čechů s národy a zeměmi jihovýchodní Evropy [Relations of the Czechs with the Peoples and Countries of Southeastern Europe], Prague 2010, pp. 167-188, here pp. 168-169. See also: Klabjan, Borut: Češkoslovaška na Jadranu. Čehi in Slovaki ter njihove povezave s Trstom in Primorsko od začetka 20. stoletja do druge svetovne vojne [Czechoslovakia on the Adriatic See. The Czechs and the Slovacs and their Connection with Trste and the Slovenian Littoral from the Beginning of the 20th century to the Second World War], Koper 2007.

- ↑ Reichert, Günter: Das Scheitern der Kleinen Entente. Internationale Beziehungen im Donauraum von 1933 bis 1938, Munich 1971; Campus, Eliza: The Little Entente and the Balkan Alliance. Bukarest 1978; Ádám, Magda: Richtung Selbstvernichtung. Die Kleine Entente 1920-1938, Budapest 1989.

- ↑ Chiper, Ioan: The Little Entente and the Versailles System. Concord and Discord at a Crucial Time (1935-1937), in: Jindra, Jiři and Tůma, Oldřich (eds.): Czechoslovakia and Romania in the Versailles System, Prague 2006, pp. 131-138.

- ↑ Solomon, Flavius: Das Europa der Nationalstaaten vs das Europa der Minderheiten. Bemerkung am Rande eines schicksalhaften Misserfolgs, in: Jindra, Jiři and Tůma, Oldřich (eds.): Czechoslovakia and Romania in the Versailles System, Prague 2006, pp. 116-130.

Selected Bibliography

- Bakke, Elisabeth: The making of Czechoslovakism in the first Czechoslovak Republic, in: Schulze Wessel, Martin (ed.): Loyalitäten in der Tschechoslowakischen Republik, 1918-1938. Politische, nationale und kulturelle Zugehörigkeiten, Munich 2004: Oldenbourg, pp. 23-44.

- Banac, Ivo: The national question in Yugoslavia. Origins, history, politics, Ithaca 1984: Cornell University Press.

- Boeckh, Katrin: Serbien, Montenegro. Geschichte und Gegenwart, Regensburg 2009: Pustet.

- Hoensch, Jörg K: Geschichte der Tschechoslowakei, Stuttgart; Berlin; Cologne 1992: Kohlhammer.

- Kalvoda, Josef: The genesis of Czechoslovakia, Boulder; New York 1986: East European Monographs; Columbia University Press.

- Kirschbaum, Stanislav J.: A history of Slovakia. The struggle for survival, New York 1995: St. Martin's Press.

- Lampe, John R.: Yugoslavia as history. Twice there was a country, Cambridge; New York 1996: Cambridge University Press.

- Lederer, Ivo J.: Yugoslavia at the Paris Peace Conference; a study in frontiermaking, New Haven 1963: Yale University Press.

- Lemberg, Hans: Der Versuch der Herstellung synthetischer Nationen im östlichen Europa im Lichte des Theorems vom nation building, in: Schmidt-Hartmann, Eva (ed.): Formen des nationalen Bewußtseins im Lichte zeitgenössischer Nationalismustheorien, Munich 1994, pp. 145-161.

- Sharp, Alan: The Versailles settlement. Peacemaking in Paris, 1919, New York 1991: St. Martin's Press.

- Teich, Mikuláš / Kováč, Dušan / Brown, Martin D.: Slovakia in history, Cambridge; New York 2011: Cambridge University Press.

- Tůma, Oldřich / Jindra, Jiří (eds.): Czechoslovakia and Romania in the Versailles System, Prague 2006: Ústav pro soudobé dějiny AV ČR.