Reaction to World War I↑

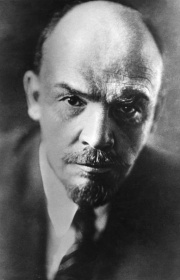

Vladimir Il’ich Lenin (1870-1924), who had given little attention to the threat to peace in Europe, responded to the outbreak of war with only weeks delay. From a Russian Social Democracy standpoint, he predicted the tsarist government’s defeat in the war and called for all socialists to adopt this revolutionary defeatism against their own governments in order to transform the imperialist war into civil war.

During the war, his book Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism (1917) served as the centerpiece of his theory. Its conclusions had been expressed in several other works published previously. Through his studies, he was able to both globalize the context and condition of the socialist revolution as an integral component of “world revolution” and situate it in the “epoch” of imperialism. Socialist revolution could be universally justified on the basis of “the actuality of the revolution.” [1]

Revolution and Peace↑

After the February Revolution, Lenin – together with other socialists – succeeded in returning to Russia with the explicit aim of overthrowing the Provisional Government. The German imperial government allowed Lenin passage through Germany, hoping to thus undermine the German enemy’s ability to continue fighting. Speculations on the role of “German gold” in the Russian Revolution have circulated since then. However, new documentary evidence has shown that Lenin received less than $40,000 worth of German money.[2] This money was primarily used to prepare for world revolution; it was decisive neither for revolution nor for war.[3]

Back in Russia, Lenin immediately denounced the country’s Provisional Government for continuing the “predatory imperialist war.” He declared that peace could only be achieved by overthrowing the bourgeois-capitalist regime and replacing it with a proletarian regime. These Bolshevik peace politics became one of the most effective weapons for seizing power. The armed insurrection in Petrograd, traditionally dated to 25 October (7 November) 1917, led to a Bolshevik-dominated Soviet government led by Lenin.

In this process, Lenin also entered into a complex relationship with world politics. Coinciding with his return to Russia, the United States, under President Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924), entered the war on the side of the Allies and insistently promoted questions of a peaceful future world order. After Lenin took over power in Russia, he declared “The Decree On Peace,” proposing “to all belligerent peoples and their governments to begin at once negotiations leading to a just and democratic peace... without annexations and contributions.” [4] Only the German government expressed its willingness to take part. The Western Allies refused to respond. Instead, President Wilson published the “Fourteen Points” (8 January 1918). This can be interpreted as a response to Lenin's Decree on Peace using somewhat similar formulas. Thus, the two declarations represent the first global competition between liberal and communist strategies for world order.[5]

Lenin and the Peace Treaties↑

As a result, negotiations began with the Central Powers, excluding the Western Allies, despite the fact that in summer 1917 Lenin had publicly denied the possibility of a “separate peace treaty with the German capitalists.”[6] Two months later, Lenin signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and Turkey), ending Russia’s commitments to the Triple Entente alliance and its participation in World War I. Russia not only lost its sovereign rights to Poland, Finland, and the Baltic States, but also had to cede almost the whole of White Russia and the Ukraine to Germany. These heavy losses sparked strong resistance among Bolshevik leaders to signing the treaty. It was only thanks to Lenin’s decisive role that the Bolshevik Party eventually accepted the treaty. In Lenin’s interpretation, the treaty gave the regime the pause that it needed to consolidate political power. At the same time, Lenin hoped for revolutions among the war-weary population in the rest of Europe, and at any rate the decay of the German and Habsburg Empires, so that the treaty could be annulled.

Indeed, on 5 November 1918, Germany renounced the treaty and broke diplomatic relations with Soviet Russia, fulfilling one of the Allies’ first conditions in the Armistice of 11 November 1918. Soviet Russia was excluded from the negotiations concerning and the signing of the Treaty of Versailles on 28 June 1919. Based on the new European order created by the treaty, Lenin hoped that Germany would be driven to cooperate and that its most revisionist politicians would even form an alliance with Russia. He expressed his belief that “the modern imperialist world rests on the treaty of Versailles...we have an alliance with all countries living under the Versailles treaty, and that is 70 percent of the whole population of the earth.”[7] Finally, he predicted that the treaty conditions prescribing the new European order would lead to the next world war.

Transforming War into Civil War↑

However, although Russia had left the battlefields of World War One, the destructive forces were channelled into the Civil War that began in 1918, devastating the vast majority of the population living within the former Russian Empire’s borders. Thus, Lenin’s campaign to turn the “imperialist war into a civil war” – the core strategy of his revolution concept[8] – had fatal consequences. The fate of the region, and the location of the eventual western border of the Soviet Union, was settled in violent and chaotic struggles over the course of the next three and a half years. In the end, the Polish-Soviet War was concluded with the Treaty of Riga in 1921. For these inhabitants, this was an extension of World War One, especially since during the first half of the civil war, troops from the remaining world powers were sent to intervene in the struggle. In the course of the civil war, both sides committed many mass crimes against the population. However, the Bolshevik regime – under Lenin’s direction – developed its repressive und terrorist traits of class annihilation that would leave their mark on society for decades to come under the ideological label of “Leninism.”

Benno Ennker, University of St. Gallen and Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen

Section Editors: Yulia Khmelevskaya; Katja Bruisch; Olga Nikonova; Oksana Nagornaja

Notes

- ↑ Lukacs, Georg: Lenin: A Study in the Unity of His Thought. London 2009 (first edition in German: Lenin. Studie über den Zusammenhang seiner Gedanken. Verlag der Arbeiterbuchhandlung, Vienna 1924.)

- ↑ Lyandres, Semion: Bolsheviks’ “German Gold” Revisited. Inquiry into the 1917 Accusations, Pittsburgh 1996.

- ↑ Sobolev, G. L.: Taina “nemetskogo zolota,” [Secrets of the “German Gold”] Moscow 2002, pp. 376f.

- ↑ Lenin V. I., Doklad o mire 26 oktyabrya (8 noyabrya) [Report on the Peace], Pol'noe Sobranie Sochinenii, t. 26 [Collected Works, vol. 26], pp. 217-221. Zaklyuchitel`noe slovo po dokladu o mire 26 oktyabrya (8 noyabrya) [Concluding words on behalf of the Report on the Peace], Pol'noe Sobranie Sochinenii, t. 26 [Collected Works, vol. 26], pp. 222-224. Dokumenty' vneshnej politiki SSSR, t. 1, [Documents of the foreign policy of the USSR, vol. 1], Moscow 1957, pp. 11—14.

- ↑ Mayer, Arno J.: Wilson vs. Lenin. Political Origins of the New Diplomacy, New Haven 1959; Hobsbawm, Eric: Age of Extremes. The Short Twentieth Century 1914-1991, London 1994, p. 67.

- ↑ Lenin, Vladimir I.: Vneshniaia politika Russkoi Revoliutsii [The Foreign Policy of the Russian Revolution] in: Lenin, V. I.: Pol’noe sobranie sochinenii, Moscow 1964, Volume 25, pp. 335f.

- ↑ Lenin, Vladimir I.: Political Report of the Central Committee RKP(b) to the Ninth All-Russian Conference of the Communist Party (20 September 1920). Document 59, in: Pipes, Richard (ed.): The Unknown Lenin. From the Secret Archive, Yale 1996, pp. 101, 103.

- ↑ Getzler, Israel: Lenin’s Conception of Revolution as Civil War, in: Thatcher, Ian D. (ed.): Regime and Society in Twentieth-Century Russia, London 1999, pp. 107-17.

Selected Bibliography

- Harding, Neil: Leninism, Durham 1996: Duke University Press.

- Lenin, Vladimir Ilʹich, Amiantov, Iu. N / Akhapkin, Iurii Aleksandrovich; Stepanov, Vladlen Nikolaevich et al. (eds.): V. I. Lenin. Neizvestnye dokumenty, 1891-1922 (Lenin, Vladimir I.. Unknown documents 1891-1922), Moscow 1999: Rosspėn.

- Lenin, Vladimir Ilʹich: Polnoe sobranie sochinenii (Collected works), Moscow 1967: Izd-vo pol. lit..

- Pipes, Richard / Brandenberger, David / Fitzpatrick, Catherine A. (eds.): The unknown Lenin. From the secret archive, New Haven 1996: Yale University Press.

- Service, Robert: Lenin. A biography, Cambridge 2000: Harvard University Press.