Early Political Career↑

Born into a successful commercial and agrarian family, Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg (1856-1921) studied law at university and, like his father and grandfather, rose to prominence in the Prussian internal administration. He became the youngest Landrat (district administrator) in the province of Brandenburg in 1886 and its youngest Oberpräsident (senior president) in 1899. In 1905 he was appointed Prussian minister of the interior and in 1907 he became both state secretary of the Reich Office of Interior and vice president of the Prussian State Ministry. Widely recognized to be a very competent bureaucrat who did not hold intransigent conservative views, he nevertheless owed his promotion largely to the favour of Wilhelm II, German Emperor (1859-1941) who shared his love of hunting and controlled all appointments to the higher state service. Bethmann was surprised to be offered position after position, effortlessly and indiscriminately. In the summer of 1909 he succeeded Bernhard von Bülow (1849-1929) as Reich Chancellor after the Reichstag rejected Bülow’s financial reform.

Chancellorship before 1914↑

Bethmann had never aspired to be chancellor and he struggled to deal with the intractable domestic and foreign policy problems he inherited. Although politically conservative, he accepted the need for moderate reforms. He tried to pursue a "diagonal policy", working with a coalition of right-wing parties and the Catholic Centre Party in the German Reichstag while not alienating left-wing liberals and the Social Democratic Party, which became the largest party in the Reichstag after the elections of 1912. Bethmann achieved a Reich financial reform and a constitution for the Reichsland of Alsace-Lorraine (annexed from France in 1871). But, unwilling to open the floodgates to democratisation in Prussia, he proved unable to reform Prussia’s inequitable three-class suffrage; and his staunch defence of army privilege in the Zabern Affair of 1913 cost him sympathy on the left.

In foreign affairs, Bethmann hoped to find a solution to the problem of Germany’s "encirclement" by the Entente powers. He lacked diplomatic training and necessarily relied on the expertise of his subordinates at the German Foreign Office, especially the state secretaries, Alfred von Kiderlen-Wächter (1852-1912) and Gottlieb von Jagow (1863-1935). After the Agadir Crisis of 1911, Bethmann was convinced that Germany had to achieve a rapprochement with Britain, but he could not modify Alfred von Tirpitz’s (1849-1930) naval armaments programme and he supported military demands for more resources. Bethmann was frequently excluded from decision-making by the Kaiser and he was not present at the "War Council" on 8 December 1912 when, under the impact of the Second Balkan War, Wilhelm II discussed Germany’s readiness for a European war with his military and naval advisers.

Bethmann and the War’s Origins↑

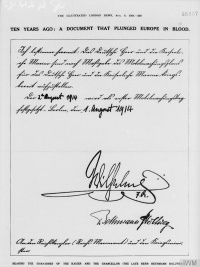

Bethmann’s role in the July Crisis of 1914 is highly controversial. While it was the Kaiser who assured the Austrians of Germany’s full support on 5 July 1914, the chancellor subsequently approved the decision and took steps during the crisis both to encourage Austrian action against Serbia and to quash attempts by other European powers to mediate. At the end of July 1914 he deliberately scuppered the Kaiser’s proposal that the Austrians should halt their military operations once they had taken Belgrade. Bethmann has consequently been seen by historians such as Fritz Fischer (1909-1999) as a warmonger. He was prepared to risk a continental war in 1914, even if he made a last ditch effort to secure British neutrality at the end of July 1914, promising in the event of a German victory to respect the territorial integrity of France (though not her colonies). Some contemporaries and historians have also seen Bethmann as a more elegiac figure, a dreamer and philosopher who did not want war but may have seen it as a way out of his political difficulties. The publication of the diaries of his private secretary, Kurt Riezler (1882-1955), appeared to substantiate this interpretation but they were substantially incomplete and subject to suspect editing. Riezler’s recently discovered letters to his fiancée indicate that Bethmann had no regrets when war broke out in 1914.

The War Years↑

Although Bethmann sometimes appeared to relish his role as Germany’s wartime chancellor, his power and influence suffered a decline. Military necessities immediately trumped political priorities, the Kaiser was sidelined, and the state of emergency at home gave significant powers to the deputy commanding generals. After the failure of the Schlieffen-Moltke Plan and the onset of a war of attrition, Bethmann had doubts about the military strategy of Erich von Falkenhayn (1861-1922), who replaced Helmuth von Moltke (1848-1916) as chief of the General Staff in September 1914, but there was no institutional mechanism for the chancellor to intervene directly in military matters. Throughout 1915 Bethmann believed that a victory in the East was possible and he increasingly looked to Paul von Hindenburg (1847-1934) and Erich Ludendorff (1865-1937) to achieve it. After the failure at Verdun in 1916, Bethmann supported Falkenhayn’s replacement by Hindenburg. But the chancellor’s authority was fatally undermined once Hindenburg and Ludendorff took over the Supreme Command.

Bethmann supported German annexations during the war even if these were relatively moderate compared to the far-reaching aims pursued by the military leadership and extreme conservatives in 1917-18. On 9 September 1914 he approved a significant memorandum, drafted by Riezler, specifying that Germany’s general aim in fighting the war was to gain security in the East and West for all imaginable time. Russia was to be thrust back to the Urals while, in the West, Bethmann supported aims that included German control of northern France, German fortifications along the Channel coast, the subjugation of Belgium and Luxembourg, and the creation of a central European customs area under German domination (Mitteleuropa). The speed with which Bethmann’s "September Programme" was drawn up has encouraged historians to see it as reflecting the pre-war ambitions of Germany’s economic, military and political elites. While it may have represented Bethmann’s maximalist negotiating position, Germany had not yet suffered the reversal of the Battle of the Marne and the chancellor’s hopes of a military victory were still high.

The military deadlock in the West eventually encouraged Bethmann to seek a political solution to the war, though not at any price. He welcomed the mediation of the United States in 1916 and, concerned about the impact on the United States, he also successfully opposed Germany’s recourse to undeclared restricted submarine warfare until March 1917 when he was overruled by the military. Bethmann’s efforts on the home front were focused on holding together the so-called “civil truce” and ensuring maximum domestic support for the war effort. Conditions at home became critical in late 1916 and Bethmann prevailed upon the Kaiser to issue his "Easter Message" of 7 April 1917, promising a reform of the Prussian suffrage and the Prussian upper house of parliament after the war. But this was too vague for the left and even Bethmann was now convinced that the three-class suffrage had to be abolished. At the same time the mere promise of reform created powerful enemies for the chancellor on the right.

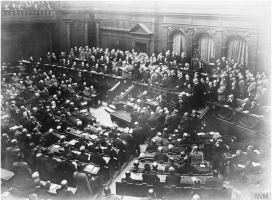

So long as Bethmann commanded support in the Reichstag, he was politically useful to the generals. But when the Reichstag majority coalesced around a peace resolution in July 1917, calling for a peace without annexations, this utility came to an end. Having apparently lost the confidence of the political parties (though not of the Kaiser), Bethmann was effectively forced by the military leadership to resign on 13 July 1917. He retired to his estate at Hohenfinow where he subsequently wrote his memoirs.

Katharine Anne Lerman, London Metropolitan University

Section Editor: Mark Jones

Selected Bibliography

- Fischer, Fritz: Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg (1856-1921), in: Sternburg, Wilhelm von (ed.): Die Deutschen Kanzler. Von Bismarck bis Merkel, Berlin 2006: Aufbau Taschenbuch.

- Jarausch, Konrad Hugo: The enigmatic chancellor. Bethmann Hollweg and the hubris of imperial Germany, New Haven 1973: Yale University Press.

- Röhl, John / Roth, Günther (eds.): Aus dem Großen Hauptquartier. Kurt Riezlers Briefe an Käthe Liebermann, 1914-1915, Wiesbaden 2016: Harrassowitz.

- Vietsch, Eberhard von: Bethmann Hollweg. Staatsmann zwischen Macht und Ethos, Boppard am Rhein 1969: Harald Boldt.