Introduction↑

In 1914, humanitarian arguments in favor of maintaining peace in Africa were brushed aside due to the threats and opportunities of war. European imperialists claimed that colonial rule would prevent ethnic conflict in Africa; and the Berlin Act of 1885 called for neutrality in the Congo Basin. Belgium, and belatedly Germany, made appeals for neutrality in Central Africa. European settlers expressed misgivings about African reactions to seeing whites killing one another.[1] British officials, however, envisioned German shortwave stations and ports in Africa supporting attacks on their shipping. British naval and colonial forces gave them military advantages they were determined to use. The French, reeling under German attack in Europe, were more than willing to cooperate in striking at their enemy in Africa.

For Africans, the result was four years of killing in a conflict not their own. John Chilembwe (1871-1915), an African Baptist minister who would lead a wartime revolt against British rule in Malawi, aptly observed that while it had been said that Africans had nothing to do with “the civilized war,” they had quickly been thrust into it.[2]

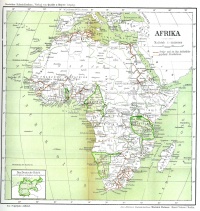

Germany had four colonies in Africa in 1914: Togo (today: Togo and territory in eastern Ghana), Cameroon (Cameroon and territory in northeastern Nigeria), German Southwest Africa (Namibia) and German East Africa (Rwanda, Burundi and Tanzania, except Zanzibar). In the event of military victory, the German Colonial Minister, Wilhelm Solf (1862-1936), advocated large-scale colonial expansion as early as the confidential September Program of 1914. Corresponding with the pre-war imperialist vision of a German Mittelafrika, Portuguese colonies, the Belgian Congo and French Equatorial Africa were to be annexed; even Nigeria might be gained in case of British defeat.[3] Wartime aspirations grew to include strategic and economically developed regions in French West Africa.

This imperialist expansion aimed to give the colonies the geographic unity and size necessary for their defense, while providing Germany an ample supply of raw materials. Although German colonial enthusiasts embraced these ambitions, the government’s priority was its European objectives. African colonial expansion could be achieved only if Germany won the war, or perhaps partially in a negotiated peace. Instead, the victory of the Allies in 1918 meant their colonial war aims were realized. The colonial repartition of the continent that followed in a sense completed the 19th century "Scramble for Africa", consolidating the empires of the victors in a fashion that reflected both their traditional imperialist ambitions and the consequences of the war.

French Aims↑

In West and Central Africa, the French desire to improve access to their colonies in the interior and the Anglo-French recognition of France’s right to colonial compensation for British expansion elsewhere were the decisive factors in determining the future of Cameroon and Togo. Throughout the war, French colonial officials emphasized the value of the two colonies as natural outlets for their West and Central African Federations.

Given its size and location, Cameroon was naturally the more important. An Anglo-French military campaign led to joint administration of the port of Duala and its surrounding area, but the British saw a condominium for the entire territory as potentially contentious. French colonialists regarded the Sangha and Lobaye corridors, ceded to Germany in 1911, as an African Alsace-Lorraine that obviously should be returned to France. Geographically, Cameroon seemed to “strangle” French Equatorial Africa. In 1917, Albert Duchêne (1866-?) of the French Colonial Ministry forcefully observed, “On the conservation of Cameroon depends the future of our Equatorial Africa. We must seek to secure it for ourselves at any price.”[4] The wartime partition of Cameroon favored French aspirations.

British Priorities↑

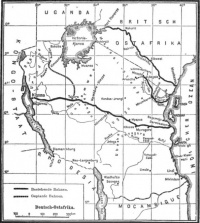

From the outset of the war, British decision makers placed a higher priority on acquiring German East Africa. Among the most important reasons for this policy was the traditional British interest in controlling the sea lanes of the Indian Ocean. German submarine warfare led to new fears at the British Admiralty that the Germans would construct naval bases in Africa. British difficulties in sinking the German cruiser Königsberg, which had found wartime sanctuary in the East African Rufiji River delta, exacerbated these anxieties. In addition, the prolonged fighting in East Africa demonstrated the danger posed by the German presence to neighboring British colonies.

The deliberations within the British government repeatedly stressed these strategic concerns, but did not lose sight of German East Africa’s economic value. In 1915, the British Colonial Secretary, Lewis Harcourt (1863-1922), summarized these benefits in a memorandum appositely named “The Spoils.” Later inter-governmental committees expanded on its arguments. The documents described German East Africa as the richest of Germany’s colonies. A land with extensive mineral resources, it also contained great agricultural potential. The Germans were credited with developing the colony’s infrastructure, including the railway from Ujiji to Dar-es-Salaam. Their successors might reap the benefits. Highland areas were considered suitable for European settlement. India’s British rulers added a further imperialist twist to this rationale: German East Africa offered a marvelous opportunity for Indian emigration.[5]

British aims reflected revived visions of a Cape-to-Cairo railway. The German colony represented the remaining obstacle to a line of contiguous British possessions stretching from South Africa to Egypt. Although many British policy makers recognized that railroad plans were impractical, they seemed unable to resist the geographic appeal.

Belgian, South African and Portuguese Colonial Objectives↑

Belgian colonial aims reflected the anxieties of a small state. Initially afraid that the Belgian Congo might be sacrificed in a compromise peace, Belgian officials later viewed offensive operations against German East Africa as a means for restoring their image in Congolese eyes while assuring themselves of colonial bargaining chips. Their leading territorial priority was increasing the Congo’s limited access to the Atlantic. How this might be achieved as an outcome of the First World War required a Machiavellian imperialist scheme.

Despite mutual recriminations, British and Belgian forces cooperated in the East African campaign. By the end of the war colonial troops from the Congo had occupied Rwanda and Burundi.[6] Belgian diplomats proposed that they would withdraw from these territories in favor of Britain; Britain would then turn over the southern part of German East Africa to Portugal; and Portugal would compensate Belgium with the northern part of Angola. These suggested imperialist territorial exchanges foundered on the adamant refusal of Portugal to surrender any of its colonial territory.[7]

The British appreciated the wartime loyalty of the Union of South Africa’s leaders and their military assistance in the prolonged East African campaign. Prime Minister Louis Botha (1862-1919) and Defense Minister Jan Christian Smuts (1870-1950) were Afrikaners who had fought against the British during the Boer War, but emerged from the conflict as supporters of reconciliation with Britain. In 1914, they agreed to a British request to seize German Southwest Africa. They saw an opportunity for both South African expansion and further Anglo-Afrikaner reconciliation. Yet before the South African Parliament they justified the action as necessary to defend the Union against German attack.[8] Only after suppressing a serious rebellion of anti-British Afrikaners were they able to occupy the German colony in 1915. British gratitude toward South Africa increased the following year, when Smuts assumed command of the campaign in East Africa and drove the German forces south from the Kenyan border.

Acquisition of Southwest Africa formed part of a larger imperialist policy pursued by Union leaders toward Southern Africa. They saw in the territory both land for poor white South Africans and diamonds for mining companies.[9] White South African leaders considered using German East Africa for their own purposes as well. Delagoa Bay had long been an Afrikaner territorial objective because it would have improved the Transvaal’s access to sea. Proposals within the South African government envisioned a territorial exchange that would give South Africa southern Mozambique while compensating Portugal with the southeastern part of German East Africa.[10]

Portuguese leaders hoped to gain the southern part of German East Africa, but without giving up any of their African territories. Although Portugal had long been Britain’s ally, London’s African intentions created considerable distrust in Lisbon. The British Ultimatum of 1890 halted Portuguese efforts to join their colonies of Mozambique and Angola, reserving Zimbabwe and Zambia for Cecil Rhodes’ (1853-1902) imperialist expansion from South Africa. Deeply humiliated, the Portuguese were further alarmed by the Anglo-German treaty of 1898 which envisioned partitioning Portugal’s African territories.[11]

Portugal entered the war in 1916 largely to protect and extend its African colonial claims. Instead, its military participation, especially in Mozambique, proved disastrous. In 1917 German forces in East Africa avoided surrendering to the British by marching into Mozambique and capturing sufficient military supplies to continue the war. Rather than help defeat the Germans, the Portuguese faced widespread revolt among the Barue that they brutally suppressed.

African Voices↑

Towards the end of the war, changing circumstances and popular attitudes in Europe propelled the debate over the future of Germany’s colonies in new directions. The war’s terrible casualties created disillusionment among both soldiers and civilians. The Russian Revolution and American President Woodrow Wilson’s (1856-1924) call for “peace without victory” offered new ideological challenges to the old diplomacy. Despite their differences, the appeals to the principle of self-determination undermined the expansionist colonial designs of the belligerents. Especially on the left, this intensified popular support for moral peace terms. If it ever had been possible to argue openly that Germany’s colonies should be annexed for purely strategic and economic reasons, the moment had passed.

In public, Allied leaders claimed that the confiscation and division of the German colonies corresponded with African wishes. In part, this argument represented the unfeigned confidence of Allied officials in the superiority of their own colonial administrations. They also produced indictments of German colonial rule, especially in German East and Southwest Africa. Frank Weston (1871-1924), Anglican Bishop of Zanzibar, issued a pamphlet in 1917, The Black Slaves of Prussia, with vivid images of German cruelty. It described the German syambok (whip) of rhinoceros hide as being designed to injure, not just to hurt.[12] The wartime administration in German Southwest Africa produced a similar denunciation of German oppression in the colony with graphic descriptions of hangings and whippings, supported by many eyewitness accounts.

During a House of Commons debate in December 1917, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George (1863-1945) promised that colonial questions would be settled on the “principle of respecting the desires of the people themselves.” He was confident about what this would mean in Germany’s African colonies, “About which tales are told that make one shudder.” The “poor, helpless people, [are] begging and craving… [that we not] ...return them to German terrorism.”[13]

Yet, Allied leaders and colonial officials were aware that they were manufacturing many of the statements of African preferences that they claimed as justification. In June, Horace Byatt (1875-1933), the British administrator of occupied territory in German East Africa, offered a far more circumspect confidential assessment than had Lloyd George. Byatt counseled, “It would be injudicious to make open and general inquiry of the natives as to whether they prefer British or German rule.”[14] Charles Dundas (1884-1956), a British officer charged with producing an indictment of German rule, later observed: “If the truth were known, the native might have said the equivalent of ‘A plague on both your houses.’”[15]

The Belgians produced a statement from Yuhi V Musinga, Mwami of Rwanda (1883-1944) praising their educational efforts in the Congo and complaining that the Germans had neglected his territory. He would “greatly rejoice” to come under Belgian rule. If this was an accurate representation of Musinga’s views, Dundas offered a fitting explanation for it and similar statements. “Africans are not so simple as to tell the victor that they prefer to be ruled by the vanquished.”[16]

More genuine statements of African opinions challenged Allied decisions, while rejecting the favorable portrait of their colonial policies. In 1918 an appeal to the British government from the South African Native National Congress, predecessor to the African National Congress, attacked the harsh discrimination in the Union of South Africa. “Unless its system of rule be radically altered so as to dispel colour prejudice,” German colonies should not be handed over to the Union Government, it declared. And rather than extend Belgian colonial administration, the memorial recommended that Belgian misrule of the Congo had made the war an opportune time to bring it to an end.[17]

The Lagos Standard, an African newspaper in Nigeria, echoed the attack on South African policies in 1919. “The rulers of South Africa have not proved themselves better than the Germans, rather, they have, in the native view point, vied with them with singular success in repressing the true owners of the land, the Natives.”[18] The newspaper, along with others in West Africa, demanded that the Allied leaders apply their professed respect for self-determination and consult the African populations of the German colonies about their future.[19]

W.E.B. Du Bois (1868-1963), the African-American scholar and Pan-Africanist, put forward a program calling for a central African state including the former German colonies as well as the Belgian Congo, and in the future perhaps Portugal’s possessions. Such a proposal, he argued, would correspond with African desires.

League Mandates↑

The creation of the League of Nations mandate system at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 and the corresponding involvement of the United States did moderate the tone of imperialism, offering an altruistic cloak to colonial expansion. At the end 1917, George Louis Beer (1872-1920), historian and African expert for the American delegation at the Peace Conference, made an early proposal for international mandates in Africa. A synthesis of Anglo-American mandate ideas emerged the following year, especially with the publication of Smuts’s tract The League of Nations: A Practical Suggestion. The pamphlet gave detailed consideration to the creation of a mandate system, and strongly influenced Wilson. However, Smuts had envisioned that the ideas of self-determination and international trusteeship might be employed only in Europe and the Middle East. Wilson insisted they be applied in Africa as well, ironically interrupting South Africa’s anticipated annexation of German Southwest Africa.[20]

At the opening of the Peace Conference, the British Dominions and the French pressed their cases for the annexation of all Germany’s colonies except East Africa. This brought a clash with Wilson, who observed that “The world would say that the Great powers first portioned out the helpless parts of the world, and then formed a League of Nations.”[21] As the British and French sought to conciliate Wilson, a compromise plan emerged, leading to the three-tier mandate system, later designated A for the former Ottoman territories in the Middle East; B for West, Central and East Africa; and C for German Southwest Africa and Germany’s former colonial possessions in the Pacific.

Soon a new clash erupted over the future training and use of African soldiers. Allied leaders denounced German colonialism for militarizing Africa, but the criticism was tinged with hypocrisy. The French tenaciously insisted on the right to raise troops in Togo and Cameroon. If Anglo-American opposition to this position seems more enlightened, it should be recognized that it coincided with the aims of South Africa’s leaders. The widespread use of African troops during the war coupled with German plans for a vast Central African Empire alarmed Pretoria. The white minority government feared that the training of black soldiers in a returned German colony could force South Africa to follow the same policy and threaten white hegemony.[22]

Conclusion↑

Despite agreement over the mandate system, forging a colonial peace settlement in Africa still roused a great deal of imperialist territorial wrangling. For example, Lloyd George observed that “Belgium asked for the most fertile portion of East Africa whereas they had not made good use of what they had on the Western side.” He dismissed Belgian military participation in East Africa and described Belgium’s request for Rwanda and Burundi as “a most impudent claim.”[23] Likewise the British rejected Portuguese claims to a mandate in the southern part of German East Africa, criticizing both Portuguese colonial practices and military participation in the war. Portugal was allowed to annex only the Kionga Triangle, a small territory on the northern border of Mozambique.

African interests, so loudly proclaimed in public as the basis for Allied policy, were largely disregarded in the decision-making process. African voices were not completely silent, but aside from the rhetoric of some statesmen, the Allied colonial powers were not listening. Instead, the repartition of Africa conformed to the differing colonial ambitions and priorities of the victorious European states. As mandates of the League of Nations, the British received most of German East Africa, while the Belgians retained Rwanda and Burundi. The Union of South Africa acquired the coveted territory of German Southwest Africa. In West Africa, the French obtained most of Cameroon and Togo as colonial compensation for British gains elsewhere in Africa. Wartime developments produced new incentives, but a strong continuity with past colonial aims persisted.

Brian Digre, Elon University

Section Editors: Melvin E. Page; Richard Fogarty

Notes

- ↑ Strachan, Hew: The First World War in Africa. Oxford 2004, p. 2.

- ↑ Shepperson, George / Price, Thomas: Independent African. John Chilembwe and the Origins, Setting and Significance of Nyasaland Native Rising of 1915, Edinburgh 1958, p. 234; see also Page, Melvin: The Chiwaya War. Malawians and the First World War, Boulder 2000, pp. 16-18. For a full discussion of African campaigns and colonial transfers see encyclopedia entry: Occupation during and after the War (Africa).

- ↑ Fischer, Fritz: Germany’s Aims in the First World War, New York 1967, pp. 102-103.

- ↑ Digre, Brian: Imperialism’s New Clothes. The Repartition of Tropical Africa, 1914-1919, New York 1990, pp. 45-48; Elango, Lovett: The Anglo-French ’Condominium’ in Cameroon, 1914-1916. The Myth and Reality, in: International Journal of African Historical Studies 18/4 (1985), pp. 656-673 and Andrew, C.M. / Kanya-Forstner, A.S.: The Climax of French Imperial Expansion, 1914-1924, Stanford 1981, p. 99.

- ↑ Digre, Imperialism’s New Clothes, pp. 85-88.

- ↑ Paice, Edward: World War I The African Front. An Imperial War on the African Continent, New York 2008, pp. 228-229.

- ↑ Digre, Imperialism’s New Clothes, pp. 186-195.

- ↑ Strachan, First World War in Africa, pp. 64-65 and Louis, William Roger: Great Britain and Germany’s Lost Colonies 1914-1919. Oxford 1967, p. 31.

- ↑ Wallace, Marion: A History of Namibia. From the Beginning to 1990, London 2011, pp. 216-217.

- ↑ Hyam, Ronald: The Failure of South African Expansion 1908-1948, London 1972, pp. 28-33.

- ↑ Newitt, Malyn: Portugal in European and World History, London 2009, pp. 191-193 and Newitt, Portugal in Africa, The Last Hundred Years, London 1981, p.33.

- ↑ Weston, Frank: The Black Slaves of Prussia, London 1918, p. 7.

- ↑ United Kingdom, Parliamentary Debates (Commons). 5th series. vol. 100 (1917), pp. 2220-2221.

- ↑ Digre, Imperialism’s New Clothes, pp. 98-101.

- ↑ Dundas, Charles: African Crossroads, London 1955, p. 106.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Digre, Imperialism’s New Clothes, pp. 126-127.

- ↑ The Late German Colonies. Lagos Standard. 13 August 1919.

- ↑ Osuntokun, Akinjide: Nigeria in the First World War, London 1979, p. 88.

- ↑ Digre, Imperialism’s New Clothes, pp. 134-144.

- ↑ U.S. Department of State. Papers relating to the Foreign Relations of the Unite States. The Paris Peace Conference, 1919. Washington, D.C. 1942-27, vol. 3, p. 768.

- ↑ Beer, George Louis: African Questions at the Paris Peace Conference, New York 1923, p. 275 and Digre, p.137.

- ↑ U.S. Department of State. vol. 3, p. 813 and vol. 5, pp. 419-420.

Selected Bibliography

- Andrew, Christopher M. / Kanya-Forstner, Alexander S.: The climax of French imperial expansion, 1914-1924, Stanford 1981: Stanford University Press.

- Digre, Brian: Imperialism's new clothes. The repartition of tropical Africa, 1914-1919, New York 1990: P. Lang.

- Dundas, Charles: African crossroads, London; New York 1955: Macmillan; St. Martin's Press.

- Elango, Lovett: The Anglo-French 'condominium' in Cameroon, 1914-1916. The myth and the reality, in: The International Journal of African Historical Studies 18/4, 1985, pp. 657-673.

- Fischer, Fritz: Germany's aims in the First World War, New York 1967: W. W. Norton.

- Gifford, Prosser / Louis, William Roger (eds.): France and Britain in Africa. Imperial rivalry and colonial rule, New Haven 1971: Yale University Press.

- Gifford, Prosser / Louis, William Roger / Smith, Alison (eds.): Britain and Germany in Africa. Imperial rivalry and colonial rule, New Haven 1967: Yale University Press.

- Grundlingh, Albert M.: Fighting their own war. South African Blacks and the First World War, Johannesburg 1987: Ravan Press.

- Hyam, Ronald: The failure of South African expansion, 1908-1948, New York 1972: Africana Publishing Corporation.

- Lettow-Vorbeck, Paul von: My reminiscences of East Africa, London 1920: Hurst and Blackett.

- Louis, William Roger: Ruanda-Urundi, 1884-1919, Oxford 1963: Clarendon Press.

- Louis, William Roger: Great Britain and Germany's lost colonies, 1914-1919, Oxford 1967: Clarendon Press.

- Michel, Marc: L'appel à l'Afrique. Contributions et réactions à l'effort de guerre en A.O.F. (1914-1919), Paris 1982: Publications de la Sorbonne.

- Osuntokun, Akinjide: Nigeria in the First World War, London 1979: Longman.

- Page, Melvin E.: The Chiwaya war. Malawians and the First World War, Boulder 2000: Westview Press.

- Page, Melvin E. (ed.): Africa and the First World War, New York 1987: St. Martin's Press.

- Paice, Edward: World War I. The African front, New York 2008: Pegasus Books.

- Samson, Anne: Britain, South Africa and the East Africa campaign, 1914-1918. The union comes of age, London; New York 2006: I. B. Tauris; St. Martins Press.

- Shepperson, George / Price, Thomas: Independent African. John Chilembwe and the origins, setting, and significance of the Nyasaland native rising of 1915, Edinburgh 1958: Edinburgh University Press.

- Strachan, Hew: The First World War in Africa, Oxford; New York 2004: Oxford University Press.

- Wallace, Marion / Kinahan, John: A history of Namibia. From the beginning to 1990, New York 2011: Columbia University Press.