Introduction↑

On 24 February 1919, as war-time recruits into the Indian Army were still being demobilized, a number of dissenting nationalists in India, including Mahatma Gandhi (1869-1948), pledged to disobey a variety of laws proposed by the viceroy and his council. Gandhi’s resolution began:

It proved a seminal moment in the political career of Gandhi, the development of the Indian National Congress (INC) and of wider anti-colonial currents in South Asia. The Rowlatt Bills (named after Sir Sidney Rowlatt (1862-1945), the president of the committee that first outlined its contents) were not withdrawn. The situation worsened. Peaceful opposition to the draconian legislation precipitated large-scale arrests, the enactment of summary punishments, and the massacre in Amritsar, and, in turn, it provided the basis for the Non-Cooperation Resolution of 30 December 1920 and the first push for Swaraj or self-rule by the INC and its allies:

Yet still the legislation and the use of extraordinary violence by the government of India remained. Colonial officials were unable to react to the demands of moderate nationalists in the present because they were haunted by spectres of revolutionary nationalisms in the past. The First World War in India was remarkable for the array of revolutionary conspiracies that threatened British rule. As Rowlatt’s initial report makes clear, it was the fear that these war-time revolutionary movements would coalesce and haunt the imperial state once more that provided the justification for permanent, preventive measures:

But what precisely were these conspiracies which loomed so large in official British policy in India? And, were these colonial anxieties justified? This article will provide some answers by charting the pre-war origins of revolutionary nationalisms in India, their interactions with South Asian émigrés in Europe, North America and South-East and East Asia and, finally, an analysis of the Ghadar Movement, which provided a locus through which differing and divergent strands of activity were drawn together during the First World War.[4]

Pre-War Revolutionary Activism↑

Organized expressions of political radicalism were present in India long before hostilities began in 1914. As Harald Fischer-Tiné has argued, it is incorrect to assume that the First World War was alone in destabilizing perceptions of the benefits and capabilities of European modernity for the colonized of Africa and Asia.[5] Jawaharlal Nehru (1889-1964) later recalled that one of his earliest political memories was his excitement at reading of Japanese victories in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905.[6] Even if members of nascent revolutionary organizations in India did not follow daily war reporting quite as scrupulously as the young Nehru, the final Japanese victory and its symbolic humbling of white prestige contributed to a new climate of anti-imperial possibilities. From 1905 on, opposition emerged within Congress to the “moderate” position of couching demand in the myths of British liberty or fair-play and the hope of winning support from British Liberals or the Labour movement:

The “New Party” – led by the troika of Bal Gangadhar Tilak (1856-1920), Lala Lajpat Rai (1865-1928) and Bipin Chandra Pal (1858-1932) or Lal-Bal-Pal – saw their rhetoric tested in the Swadeshi Movement in Bengal which began in order to resist the administrative division of the province of Bengal for purely political purposes.[8] After July 1905, it metamorphosed into a mass boycott and burning of foreign (British) goods.

The growing dissatisfaction with the line that separated illegitimate from legitimate activity in Swadeshi, violence from non-violence, created a demand for even more radical action. Secret societies were formed among young, urban, educated, mostly high-caste, male elites promoting revolutionary terrorism. These arose mainly in Bengal in Eastern India – the Anushilan Samiti (Self-Culture Association) in 1902 and then the Dhaka Anushilan Samiti and Jugantar (New Era) group from 1905-1906 – but not exclusively so. Parallels can be found in western India in the Bombay Presidency where V.D. Savarkar (1883-1966) helped to form the Mitra Mela (Band of Friends) in 1900 and Abhinava Bharat (Young India) in 1904. All these groups held an intellectual-romantic attachment to the ideal of the secret society – often basing their neophyte organizations on the Russian nihilists (or rather depictions of Russian nihilists in late Victorian British publications).[9] And, all advocated for the use of robberies or dacoities to secure funds clandestinely, and of political assassinations as a means of initiating political change (most notably the assassination of Sir William Hutt Curzon Wyllie (1848-1909), aide-de-camp to the Secretary of State for India, in London on 1 July 1909[10] and the near escape of Charles Hardinge, Baron Hardinge of Penshurst (1858-1944), Viceroy of India, during the Delhi Durbar[11] of 23 December 1912). The wealth and social status of the men involved enabled the very earliest of revolutionary societies to have an international dimension. As youthful revolutionaries became students or businessmen abroad, they met and attached themselves to older Indian émigrés who were themselves moving seamlessly through the radical movements of their time: Shyamji Khrisnavarma (1857-1930) with the Clan na Gael, Bhikaiji Rustom Cama (1861-1936) and Sardar Singh Rahabhai Rana (1878-1957) with the British Suffragettes and the Stuttgart Conference of the Second International and Har Dayal (1884-1939) with the Industrial Workers of the World.[12]

Migration, Revolt and Mutiny During the First World War↑

During the First World War the engine of revolutionary activity shifted from cosmopolitan elites in India to semi-permanent communities of migrant labourers abroad. The largest proportion of these came from Punjab in north-west India and were largely (although not exclusively) Sikh. Emigration from Punjab, from communities that were colonized but favoured with British patronage after the "Mutiny" of 1857, was a product of British imperialism. It was dependent on constant British neuroses of the fragility of the Empire and of imminent, colonial collapse. The Sikh policeman and soldier became a staple in settlements across South East Asia after their introduction into the Hong Kong Police in 1867, the Perak Armed Police in 1873 (which soon became the Malay States Guides) and the Hong Kong and Singapore Royal Garrison Artillery from 1881 on. But, other migrations also occurred unconnected with the extreme exigencies of defending or policing the British Empire. Beginning in the 1880s, men from the same communities and villages migrated as labourers to Australia, New Zealand, Fiji and, finally, logging and railroad camps, timber-mills and large farms along the Pacific Coast of North America (California, Oregon, Washington and British Columbia). These two migrations from Punjab – as colonial policemen and colonial labourers – were intimately connected. A large number of migrants were former soldiers (between half to three-quarters of the total), hoping to ease their entry abroad by invoking their former imperial service and funding their migrations through the gratuities they received upon discharge.[13] The ease with which a Punjabi sipahi (soldier or policemen) could become a chaukidar (guard, doorman or watchmen) and then a mazdur (labourer) was conditioned by the effects of colonialism at home. Punjab was on the same arc of rural underdevelopment that plagued the rest of colonial India. Colonial officials were constantly concerned about the levels of rural indebtedness in the very districts from which the Indian Army gained its recruits: “The small holder is faced with two alternatives. Either a supplementary source of income must be found, or he must be content with the low standard of living that bondage to the money-lender entails. The bolder spirit joins the army [...] the more enterprising emigrate.”[14] In 1907, in response to epidemics of bubonic plague and malaria (leading to 2 million deaths in the province of Punjab), increasing rural landlessness, the failure of the cotton crop and the “Colonization Act” (subverting previous rights of tenure and increased water rates for irrigation), Punjab became embroiled in rural agitation.[15] The movement gave Punjabis a revolutionary rhetoric and symbols and, through the arrests and transportation of Sardar Ajit Singh (1881-1947) and Lala Lajpat Rai (1865-1928), their own revolutionary martyrs.[16]

The first political organizations among Punjabi labourers in North America arose in the context of anti-immigrant racism. The reaction to the presence of Punjabi migrants in Canada and the United States of America was unambiguously hostile, even though the numbers of actual migrants remained small (between 1900 and 1920 only 5,351 “East Indians” were admitted into Canada and 7,324 into the United States[17]). Race riots, moratoria on South Asian migration, the denial of entry to wives and dependents and attempts to impose colour-bars on certain forms of industry became unforgiveable wrongs for men who still saw themselves as imperial loyalists and British subjects:

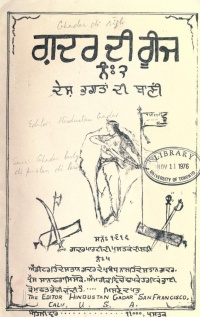

Ethnic, religious and national markers of identity suddenly came to the fore. The search for a common rhetoric with which to articulate their grievances united labourers with Sikh religious reformers[19] and more politicized students, merchants, intellectuals and religious figures who had been on the periphery of pre-war radical movements.[20] Early organizations representing migrants in North America tried to appeal to the Imperial State for relief, most notably when the Khalsa Diwan Society and the United India League sent a joint delegation to London and India in February 1913. The three-man deputation was ignored (in London), informed that nothing could be done (in New Delhi) and threatened with arrest (in Lahore).[21] With avenues of appeal closed, India was redeemed in the eyes of those who had left it as a space that could fulfill aspirations of wealth and social status denied Indians abroad. The Hindustani Association of the Pacific Coast was formed in May 1913, uniting the various associations and organizations that littered Indian migrant enclaves in Canada and the U.S.A. It established a printing press at the “Yugantar Ashram” in San Francisco, and established a newspaper entitled Ghadar. The newspaper’s name, “Mutiny” or “Rebellion,” accurately reflected the nature of its content: the desire to forcibly expel the British from India. An Urdu edition was established first on 1 November 1913 and a Gurmukhi (Punjabi) version on 9 December 1913. The different versions of the same newspaper reflected the bifurcated nature of its leadership which was divided between student-intellectuals and Punjabi labourers. The former produced a series of articles and publications in the same register as earlier revolutionary societies in India, drawing inspiration from international events:

The Gurmukhi content differed in tone, placing revolution within Sikh and Punjabi religious and literary tales of masculinity, martyrdom and self-sacrifice:

In the moonlight you have slept, but see now that the sun has risen.

You are in the clutches of a nightmare. It will not leave you without taking your life.

The red serpent is all around you. Where are your war flags?

How have we become short-statured and cowards.[?] Where are our youths who are eight feet tall?

We cowards survive today without self-respect. Where are the heroes of the country?

Today we are called dirty, black people [kala log]. Where is India’s glory?

When they confiscated our India, where did they misplace our religion?

One who cannot swim the river cannot live in a seastorm; prepare to fight.

You are sluggish and keep sitting drugged. O idiots, where is your intellect?

Had brave Hari Singh been alive, he would have taken up the sword.

He would have sacrificed his life for self-respect, the same as the lion-hearted Shivaji.

You cowards are afraid of death. How can you think of becoming lions in battle?

One hero should stand against one hundred and twenty-five thousand. That is the order of the Guru.

You sons of the Guru are Singhs, and there is much oppression. Where are your lion-like traits?

Oh ye brave Singhs, join together to gather up the dropped pearls. Why must all be lost?

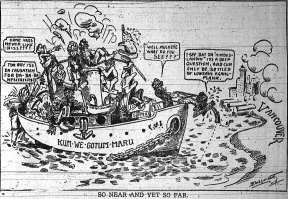

We will fight for India, we will kill and be killed. Cry loudly! Where is your tongue and heart?[23]The Ghadar Party, as the Hindustani Association of the Pacific Coast soon came to be known, was an unlikely focus for post-war colonial neuroses even with the wide circulation of its publications[24] and the opportunities for unrest provided by the outbreak of the First World War. There was no systematic planning to complement the romantic aspiration of returning to India to orchestrate an uprising of the type seen in 1857: “What is our name? Revolt. What is our work? Rebellion. Where will the mutiny break out? In India. When? In a few years.”[25] Ghadar was monitored by British intelligence from its inception,[26] its early leaders were arrested and deported[27] and there was little enthusiasm or support for Ghadar among German diplomatic staff in the United States.[28] Plans of what to do upon arrival in India were only hurriedly sketched out a few weeks after the start of the First World War and only as migrant labourers-turned-revolutionaries were already en route to India. The trigger for the return to India was a local incident – passengers aboard the S.S. Komagata Maru were refused entry into Vancouver between May and July 1914 – and the shootings and mass-arrests that occurred when its passengers arrived in Calcutta.[29] Campaigns were organized to raise money and purchase food and necessities for the stranded passengers. The funds collected became the means to buy passage back to India after individuals heard of what had befallen the Komagata Maru’s passengers and rumours circulated of the discontent it had caused in Punjab circulated.[30]

From 29 August 1914, up to 5,000 returned migrants filtered through into rural Punjab.[31] Some of those who originally intended to go to India were diverted to trying to win over the South Asians they met in ports of call across East and South-East Asia;[32] others were arrested in Calcutta or had lost interest in the cause by the time of their return. Those who made it were disjointed and disorganized, often only meeting each other by accident, and even then unsure of what action to take or if there even was a larger plan. Ghadar devolved into unconnected low-scale violence – reflecting the interests of the small bands involved. Some tried to raid government magazines in the hope that they could gain access to rifles rather than pistols or the swords and axes that littered rural Punjab. Others tried to loot divisional and sub-divisional treasuries in an attempt to liberate the money their families had paid in tax. Still more settled for singling out local moneylenders and village headmen for public beatings and executions.[33] More concerted action was taken after members of Ghadar reached out to members of Jugantar (one of the pre-war Bengali secret societies) in hiding in Benares[34] in order to gain access to more arms and home-made explosives. A date was fixed – 21 February 1915 – upon which members of Ghadar were to attack Lahore Cantonment. “Bombs were prepared, arms got together, flags prepared, a declaration of war drawn up, instruments for destroying railways and telegraph wires collected and everything was put hastily in train for the general rising on the 21st February.”[35] Efforts were made to secure support from active soldiers by former comrades or relatives (some members of Ghadar even re-enlisted in the Army for that purpose). The 23rd Cavalry at the Lahore Cantonment at Mian Mir and the 26th Punjabis at Ferozepur promised to defect en masse; soldiers in the 128th Pioneers, 12th Cavalry at Meerut and 9th Bhopal Infantry in Benares promised that they would do something if other battalions and squadrons defected. It was decided that the liberation of Lahore was to be the signal for a general rising by soldiers who had already committed themselves to the cause and an inspiring example for the majority of soldiers and civilians in India who would be caught unaware. “The idea,” the Lieutenant-Governor of Punjab later wrote, “was not fantastic, for it had penetrated as far down as Bengal and was known to the disaffected elements in Dacca.”[36]

The promised rising never occurred. A police spy, Kirpal Singh, managed to infiltrate the circle of Lahore conspirators and police raids were launched on Ghadar enclaves in Punjab and elsewhere in India on 19 February 1915. Afterwards, the movement continued spasmodically for another several months: men who threatened to give King’s Evidence were killed, a last-ditch attempt at a rising involving the 12th Cavalry at Meerut was made in mid-March and a poorly-implemented plan to create a Ghadar training camp on the Thai-Burma border was launched. Even after it was clear that there were no hope for a war-time rebellion in India, the Ghadar press in San Francisco continued printing its material. By the end of the First World War, however, the use of mass-arrests, internment and trials/tribunals ensured that the Ghadar Party had effectively been quashed.[37] A total of 274 individuals were tried in India, Burma and the United States, forty-six were hanged, sixty-nine awarded transportation for life (rarely better than a death sentence)[38] and 106 awarded lesser terms ranging from fourteen years’ transportation to shorter terms of imprisonment.[39] Some evaded arrest altogether and drifted into movements not associated with Ghadar – especially the Indian Independence Committee in Berlin and German-funded pan-Islamist movements in Afghanistan[40] – but these remained small, elite, diasporic groupings unable to penetrate into India or make much impact until the end of the First World War. Those that remained in the United States were plagued by a factional struggle between student-intellectuals and Punjabi labourers – the latter accused of impropriety, the former (not unreasonably) of embezzling funds.

Significance and Legacies↑

But if Ghadar was a failure, how are we to account for the hyperbole and over-reaction of the colonial state in India? Ghadar was seen as so toxic that, in later years, even reproducing the stanzas and rhetoric of its propaganda was regarded as dangerous for the maintenance of colonial order and rule:

The answer lies in more than just the peculiar nature of British imperialism, which was always prone to sketch out phantasms of disorder and spectres of colonial collapse in order to justify measures that were unjustifiable elsewhere. The significance of Ghadar, both for the British Raj and for historians judging its impact, lies in its very novelty: that the interconnected global web of Empire that was for Britain a strength (not least in times of war) could yet be the source of an anti-imperial movement; that colonial essentializations of effeminacy, masculinity and loyalty were impossible to maintain under the fluidity of the imperial modern. And, that Ghadar, even after its defeat, lived on in the minds of later generations of South Asians trying to imagine a revolutionary anti-colonialism:

Not a shot in the dark

This is a warning

The sleeping tiger awakes each and every morning

The time is now ready to burst the imperial bubble

My act of revenge is just a part of the struggle.

A bullet to his head won’t bring back the dead

But it’ll lift the spirits of my people![42]

Gajendra Singh, University of Exeter

Section Editor: Santanu Das

Notes

- ↑ “The Satyagraha Pledge.” The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi (Electronic Book) [hereafter CWMG], Vol. 17, Apr. 26 1918 – Apr. 1919, (New Delhi, Publications Division, Government of India, 1999), p. 297: http://www.gandhiserve.org/cwmg/VOL017.PDF (retrieved: 16.10.2014).

- ↑ “Draft Resolution on Non-Co-Operation” [Resolution adopted by the Nagpur Session of Congress on 30 December 1920)]. CWMG, Vol. 22, Nov. 15 1920 – Apr. 5 1921, p. 163: http://www.gandhiserve.org/cwmg/VOL022.PDF (retrieved: 16.10.2014).

- ↑ East India (Sedition Committee, 1918). Report of Committee Appointed to Investigate Revolutionary Conspiracies in India, 1918. House of Commons Parliamentary Papers. Chapter XV: Summary of Conclusions: http://parlipapers.chadwyck.co.uk/home.do (retrieved: 16.10.2014).

- ↑ Ghadar is an event and a movement that is often referred to but rarely explored in detail in academic literature. In the last thirty years, Harish Puri’s Ghadar Movement and Maia Ramnath’s Haj to Utopia are the only published analyses of the origins and implications of the Ghadar movement. Both remain flawed histories. Both Puri and Ramnath efface the presence of Ghadaris by their desire to fit Ghadar into their ideal type of revolution (Marxist-Leninist in the former case, Anarchistic in the latter). Arun Coomer Bose’s Indian Revolutionaries Abroad, Kalyan Kumar Banerjee’s Indian Freedom Movement: Revolutionaries in America and Khushwant Singh and Satindra Singh’s Ghadar 1915 are the best of the older histories of the movement (remaining useful if dated). Sohan Singh Josh’s Hindustan Hindustan Gadar Party is a short history of the movement by one its adherents (and the only such narrative published in English). The other items mentioned in the Selected Bibliography help to place Ghadar in its wider contexts. This includes pre-war revolutionary activity in India (N. Gerald Barrier, Harald Fischer-Tiné, S.N. Aggarwal, Peter Heehs, Sumit Sarkar, Maya Gupta and Amit Kumar Gupta), colonial Punjabi migration and ‘nativism’ in Canada and the United States of America (Tony Ballantyne and Hugh Johnstone), pan-Islamism (K.H. Ansari), the Indian intellectuals involved in Ghadar (Emily Brown) and Ghadar in the evolution of Anglo-American Intelligence (Richard Popplewell). This list provided in the bibliography, of course, is in no exhaustive and is merely a selected sample of the wider literature.

- ↑ Fischer-Tiné, Harald: Indian Nationalism and the “World Forces.” Transnational and Diasporic Dimensions of the Indian Freedom Movement on the Eve of the First World War, in: Journal of Global History 2/3 (2007), pp. 325-324.

- ↑ Nehru, Jawaharlal: Toward Freedom: The Autobiography of Jawaharlal Nehru, New York 1941, pp. 29-30.

- ↑ “Tenets of the New Party,” Calcutta, 2 January 1907; Tilak, Bal Gangadhar: His Writings and Speeches. Appreciation by Babu Aurobindo Ghose, Madras 1922, pp. 56-64.

- ↑ Herbert Hope Risley (1851-1911) who was, at the time, Home Secretary and member of the Viceroy’s Council, commented that “Bengal united is a power; Bengal divided will pull in several different ways. That is perfectly true and one of the merits of the scheme. [...] It is not altogether easy to reply in a despatch which is sure to be published without disclosing the fact that in this scheme as in the matter of the amalgamation of Berar to the Central Provinces one of our main objects is to split up and thereby weaken a solid body of opponents to our rule.” Sarkar, Sumit: Modern India: 1885-1947, New Delhi 1983, p. 107.

- ↑ Both Jatindranath Banerji (1877-1930), one of the founders of the original Anushilan Samiti, and Savarkar are known to have devoured the two volumes of Thomas Frost’s The Secret Societies of European Revolution, 1776-1876 (London 1876) and strove to model their own societies on the Russian nihilists of the 1860s (or rather how Frost depicted them). Gupta, Amit Kumar: Nationalist Revolutionism in India, 1897-1938. In: Gupta, Maya/Gupta, Amit Kumar (eds.): Defying Death: Struggles Against Imperialism and Feudalism, New Delhi 2001, pp. 40-41.

- ↑ “Just as the Germans have no right to occupy this country, so the English people have no right to occupy India, and it is perfectly justifiable on our part to kill the Englishman who is polluting our sacred land.” Statement of Madan Lal Dhingra, 19 July 1909. The Proceedings of the Old Bailey: London’s Central Criminal Court, 1674-1913: http://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?id=t19090719-55&div=t19090719-55&terms=Dhingra#highlight (retrieved: 16.10.2014).

- ↑ The Delhi Durbar was a ceremonial procession through Delhi on the occasion of the transfer of the capital of British India from Calcutta to Delhi.

- ↑ Clan na Gael being the Irish Republican organization in the United States of America; the Second International, an international organization of socialist and labour parties that met annually from 1889 to 1916; and the Industrial Workers of the World, or “Wobblies,” a revolutionary organization promoting change through industrial unionism that grew in prominence in the American West in the 1910s and 1920s.

- ↑ According to a report compiled by Dady Burjor, the U.S. Immigration Department’s official translator in San Francisco, 75 percent of Indian migrants into the United States and Canada were Sikhs, over half were former soldiers or policemen in the British Indian Army and Hong Kong Police and all hailed from five districts in Punjab (the largest proportion being from Jullunder and Hoshiarpur). Puri, Harish K.: Ghadar Movement: Ideology, Organization & Strategy, Amritsar 1983.

- ↑ Darling, Malcolm Lyall: The Punjab Peasant in Prosperity and Debt. London 1928, p. 28.

- ↑ See Barrier, N. Gerald: The Punjab Disturbances of 1907: The Response of the British Government in India to Agrarian Unrest, in: Modern Asian Studies 1/4 (1967), pp. 353-383.

- ↑ ‘Oh Peasant, take care of thy turban! Your crops are ravaged by locusts, your garb is poor; Famine has taken its toll, your family mourn, Oh Turbaned One! Landlords have set themselves up as your leaders, In order to trap and exploit you, Oh Turbaned One! India is your Temple and you its acolyte. How long will you remain asleep? Prepare yourself to fight and to be further oppressed, Oh Turbaned One! Love your country, as Ranjha loved Heer. Walk with care, Oh Brave One, But shed all cowardice. Be united, and shout your defiance! Join hands and together put up a brave front. Oh Peasant, take care of thy turban! Translated version of “Pagri Sambhal Jatta!” composed by Prabh Dyal to open the largest meeting of the 1907 Agitation in Lyallpur, Punjab on 22 March 1907. Numerous, competing versions now exist in folksong and memory (most recently by Rabbi Shergill). Translation is the author’s.

- ↑ Chandrasekhar, S.: Indian Immigration in America. In: Far Eastern Survey 13/15 (1944), pp. 138-143, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3021823 (retrieved: 21.10.2014).

- ↑ Singh, Sant Teja (ed.): The Aryan 1/5 (December 1911).

- ↑ Individuals associated with the Tat Khalsa programme of the Chief Khalsa Diwan (Sant Teja Singh (1877–1965), Bhai Bhag Singh (1872-1914), Balwant Singh).

- ↑ Taraknath Das, Guran Ditta Kumar, Husain Rahim, Har Dayal, Sohan Singh Bhakna, Bhai Bhagwan Singh, Kartar Singh Sarabha, Maulana Barkatullah et al. Harish Puri provides the most comprehensive (if now slightly dated) analysis of the social origins of Ghadar in Puri, Harish K.: Ghadar Movement: Ideology, Organization & Strategy, Amritsar 1983, chapters 1 and 2.

- ↑ “The delegates on this asked for an interview with me. I had a long talk with them and repeated my warning [that their tone was liable to get them arrested]. Two of them were oily and specious; the manner of the third seemed to be that of a dangerous revolutionary [...].” O’Dwyer, Michael: India As I Knew It, 1885-1925. London 1925, p. 191.

- ↑ “The Trumpet of War: Commencement of the Great War.” In: Ghadar, 4 August 1914.

- ↑ Poem Three of Ghadar di Gunj (Echoes of Rebellion), San Francisco 1914. Translation is the author’s.

- ↑ Ghadar’s reach extended through networks of trans-Pacific Punjabi migration (Hong Kong, Shanghai, Singapore, Manila, Batavia/Jakarta, Bangkok, Malaya) and to Indian soldiers serving in France beginning in October and November 1914.

- ↑ Ghadar, 1 November 1913.

- ↑ Or, more specifically, agents of John Arnold Wallinger’s Indian Political Intelligence Office (IPI).

- ↑ Bhai Bhagwan Singh (1884-1948) was deported from Canada on 18 November 1913. Har Dayal, who ran the printing press in San Francisco and wrote the majority of Ghadar’s early Urdu material, was arrested by U.S. authorities in April 1914 and forced to flee to Switzerland. Both cases of arrest and deportation were orchestrated by William Hopkinson (1880–1914), an immigration translator/inspector and agent for Wallinger’s IPI.

- ↑ Johann Heinrich von Bernstorff (1862-1939), the German Ambassador in Washington from 1914 to 1916, dismissed Ghadar’s activities as an absolute “wild-goose chase.” Count Bernstorff: My Three Years in America. London 1920, p. 102. In the spring of 1915 the German Consulate in San Francisco did begin to work with the Ghadar Party headquarters in San Francisco but only so that it could utilize its trans-Pacific network in a failed scheme to funnel arms to Bengali revolutionaries (the Annie Larsen/Maverick scheme). It has often been argued that the arms found aboard the Annie Larsen, which were meant to be transferred aboard the Maverick, were intended for Punjab and Ghadari revolutionaries. This is incorrect and is the result of deliberate misinformation spread by the Indian Political Intelligence Office to secure the conviction of men associated with Ghadar in San Francisco in 1917-1918. This is clear from both Indian and British sources. See Roy, M.N. (Narendranath Bhattacharya): M.N. Roy’s Memoirs. Bombay 1964. See also: East India (Sedition Committee, 1918).

- ↑ The S.S. Komagata Maru was a steamer carrying 376 Indian passengers and was charted to circumvent stringent Canadian immigration requirements (that migrants must come to Canada by a continuous voyage from their native land). It arrived in Vancouver on 23 May 1914 but was prevented entry. Its passengers fought off attempts to board and arrest “ringleaders” among them. The would-be migrants aboard the Komagata Maru were finally forced to journey to Kolkata at the end of July 1914 (after threats that it would be fired upon by the HMCS Rainbow), and, upon arrival on 26 September 1914, were fired upon by British authorities after being accused of possessing arms and resisting arrest (twenty passengers were killed and over 100 were arrested).

- ↑ “The English turned out four hundred Sikh, Hindu and Muhammedan passengers of the Komagata Maru from Canada [...]. All these were kept without food on the ship and then the English army fired shots at the Sikhs, Hindus and Muhamadans when they reached India. They killed twenty Sikhs, Hindus and Muhammadans and injured one hundred and then imprisoned the rest. In Delhi the innocent Indians were hanged. Temples, Gurdwaras and Mosques were demolished; that is the [sic.] English commit all these oppressions on the strength of the Indians soldiers. […] We, the Indian soldiers, are making India and the whole world slaves […].” “The Day of Liberty Has Come” [leaflet, not dated]. RG 118, Records of the Office of the U.S. Attorney, Northern District of California, Neutrality Case Files, 1913-1920. National Archives at San Francisco, San Bruno, California. NRHSA Accession #’s 118 72-001, 118-73-001.

- ↑ According to the Rowlatt Committee, 331 persons were interned in Calcutta as part of the hastily-passed Ingress into India Ordinance on 5 September 1914 and a further 2,576 had their movements restricted to their villages of origin in Punjab. That left an estimated 5,000 who were not intercepted. East India (Sedition Committee, 1918).

- ↑ They won over recruits in Manila, Shanghai and Hong Kong. Some efforts were also made to propagandize among serving soldiers. The only successes members of Ghadar had among soldiers were Sikhs of the Malay States Guides and the 130th Baluchis in Rangoon. The mutiny of the 5th Light Infantry in Singapore in February 1915 was unconnected to Ghadar. For more on the Mutiny of the 5th Light Infantry see Kuwajima, Sho: The Mutiny in Singapore: War, Anti-War and the War for India’s Independence, New Delhi 2006 and Singh, Gajendra: The Testimonies of Indian Soldiers and the Two World Wars: Between Self and Sepoy. London 2014.

- ↑ After the Sahnewal Dacoity, 23 January 1915, Khushi Ram’s (a local Sahukar or money-lender) body was later found and “had numerous abrasions, incised and lacerated wounds, that he had been very roughly handled, 9 ribs on one side and one on the other being fractured, causing injuries to the lungs, and that death was due to the injuries to the lungs and shock.” During the Mansuran Dacoity, 27 January, the Sud or loan-shark was not present, so his family were targeted for beatings and his books and receipts set alight: “Indoors meanwhile the house was rifled, a woman and a boy assaulted, and then the party proceeded to the Sud’s shop, forced I open with a hammer, went inside and tried to burn the books. [...] some receipts were burnt, cloth stolen, and boxes od gold and silver ornaments rifled [...].” Lahore Conspiracy Case: Judgement. In re. King Emperor Versus Anand Kishore and Others. Charges under Sections, 121, 123, 396 and Others. India Office Records, Asia and Africa Collection, British Library, L/PJ/6/1405.

- ↑ Specifically Rash Behari Bose (1886-1945) and Sachindranath Sanyal (1893-1942).

- ↑ Lahore Conspiracy Case: Judgement.

- ↑ O’Dwyer, India As I Knew It 1925, p. 200.

- ↑ A total of twenty two trials of Ghadaris or relating to Ghadar took place in Punjab, Burma and the United States of America.

- ↑ Transported convicts were shipped a penal colony in the Andaman Islands. The death rate – an average of 37.65 percent of convicts died per year between 1910 and 1919 – made the penal colony a traumatic place of bereavement and loss. Report of the Indian Jails Committee, 1919-1920 (1921). House of Commons Parliamentary Papers.

- ↑ 274 (Indian) individuals were tried in the various cases. A further twenty German diplomatic staff or German-Americans were tried in the United States. Excluding the Benares Conspiracy Case, thirty six were acquitted; seventeen were acquitted but discharged from Government service (the police or army); two turned approvers; two were killed during the course of trials; ten absconded and escaped punishment; forty six were hanged; sixty nine awarded transportation for life; 106 awarded sentences ranging from fourteen years’ transportation to sixty days’ imprisonment (the sentences in the United States were far lighter in comparison to those in British India).

- ↑ See Ansari, K.H.: Pan-Islam and the Making of the Early Indian Muslim Socialists. In: Modern Asian Studies 20/3 (1986), pp.509-537; Ramnath, Maia: Haj to Utopia: How the Ghadar Movement Charted Global Radicalism and Attempted to Overthrow the British Empire, Berkeley 2011.

- ↑ East India (Sedition Committee, 1918 ): https://archive.org/details/seditionreport00indirich (retrieved 16.10.2014).

- ↑ Excerpt from “Assassin”; Asian Dub Foundation, Rafi’s Revenge, (London: Polygram Records, 1998). The song commemorates the assassination of Sir Michael O’Dwyer in 1940 by Udham Singh (who took on the nom de guerre Ram Mohamed Singh Azad) in retribution for the Amritsar massacre. Udham was an associate of Ghadar survivors in the mid-1920s (in particular Sohan Singh Bhakna).

Selected Bibliography

- Aggarwal, Som Nath: The heroes of Cellular Jail, New Delhi 2006: Rupa & Co.

- Ansari, K. H.: Pan-Islam and the making of the early Indian Muslim socialists, in: Modern Asian Studies 20/3, 1986, pp. 509-537.

- Ballantyne, Tony: Between colonialism and diaspora. Sikh cultural formations in an imperial world, Durham 2006: Duke University Press.

- Banerjee, Kalyan Kumar: Indian freedom movement revolutionaries in America, Calcutta 1969: Jijnasa.

- Barrier, N. Gerald: The Punjab disturbances of 1907. The response of the British government in India to agrarian unrest, in: Modern Asian Studies 1/4, 1967, pp. 353-383.

- Bose, Arun: Indian revolutionaries abroad, 1905-1922. In the background of international developments, Patna 1971: Bharati Bhawan.

- Brown, Emily Clara: Har Dayal. Hindu revolutionary and rationalist, Tucson 1975: The University of Arizona Press.

- Fischer-Tiné, Harald: Indian nationalism and the 'world forces'. Transnational and diasporic dimensions of the Indian freedom movement on the eve of the First World War, in: Journal of Global History 2/3, 2007, pp. 325-344.

- Gupta, Maya / Gupta, Amit Kumar (eds.): Defying death. Struggle against imperialism and feudalism, New Delhi 2001: Tulika.

- Heehs, Peter: The bomb in Bengal. The rise of revolutionary terrorism in India, 1900-1910, Delhi; New York 1993: Oxford University Press.

- Johnston, Hugh J. M.: The voyage of the Komagata Maru the Sikh. Challenge to Canada's colour bar, Vancouver 1989: University of British Columbia Press.

- Josh, Sohan Singh: Hindustan Gadar Party. A short history, New Delhi 1977: People's Publishing House.

- Popplewell, Richard J.: Intelligence and imperial defence. British intelligence and the defence of the Indian Empire, 1904-1924, London; Portland 1995: F. Cass.

- Puri, Harish K.: The Ghadar movement. Ideology, organisation & strategy, Amritsar 1983: Guru Nanak Dev University Press.

- Ramnath, Maia: Haj to utopia. How the Ghadar movement charted global radicalism and attempted to overthrow the British Empire, Berkeley 2011: University of California Press.

- Sarkar, Sumit: The Swadeshi movement in Bengal, 1903-1908, New Delhi 1973: People's Pub. House.

- Singh, Khushwant / Singh, Satindra: Ghadar 1915. India's first armed revolution, New Delhi 1966: R & K Pub. House.