Introduction↑

In Britain and Ireland, in the decade before World War I, a radical minority within the growing movement demanding the parliamentary franchise for women adopted militant tactics. This development can be dated to the establishment of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) at the home of Emmeline Pankhurst (1858-1928) on 10 October 1903. Pankhurst, with roots in Manchester’s radical milieu, had been active in the Independent Labour Party for a decade and, at first, the WSPU’s ethos reflected that background. Within two years, WSPU members began to deploy forms of aggressive protest calculated to draw a repressive response from the authorities and so, in turn, multiply the opportunities for publicity. In 1906, the Daily Mail, with derogatory intent, labelled these radicals “suffragettes”. Subsequently, they embraced the name, and it is the name by which they are remembered, distinguishing them from the more moderate suffragists who were members of organisations such as the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS).

Methods↑

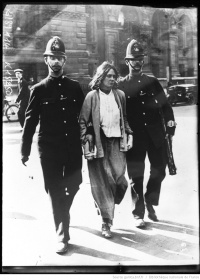

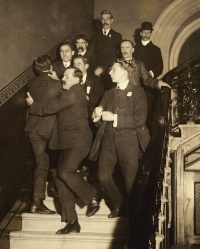

Insisting on “deeds not words”, suffragette activities escalated from heckling politicians to illegal assembly, assaulting police, boycotting the census, smashing windows, pouring acid into post boxes, vandalizing sports facilities, arson, and planting explosives. By 1913, reflecting the heightened, defiant tone that was typical of its editor Christabel Pankhurst (1880-1958), The Suffragette carried a regular two-page feature on “the reign of terror”.[1] By the outbreak of the war, these radical women – and a few male supporters – had begun more than 1,000 terms of imprisonment, although these were not always completed. While in detention, they transformed prisons into sites of the conflict by demanding separate treatment as “political prisoners” and pursuing this aim through organized protest, including hunger strikes.

Divisions↑

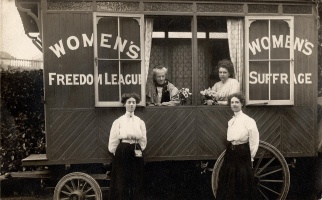

These developments discomfited not only politicians and the various state functionaries with whom the militants forced a conflict, but also moderate “constitutional” suffragists, who continued to favour persuasion as the most effective means of winning the vote. Furthermore, the militant movement itself fragmented. In November 1907, a breakaway group, disgruntled at the lack of democratic structures within the WSPU, and at the Pankhursts’ dominance of it, established the Women’s Freedom League (WFL). In 1912, the Pankhursts effectively expelled Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence (1867-1964) and Frederick Pethick-Lawrence (1871-1961), two key figures and the editors of the then WSPU newspaper Votes for Women. The Pethick-Lawrences had voiced concerns about the effectiveness of increasing militancy. In early 1914, a decisive break came with Sylvia Pankhurst (1882-1960) and her semi-autonomous East London Federation of Suffragettes (ELFS): Sylvia Pankhurst’s vision of the suffrage cause remained too intermeshed with socialism for her sister and mother. In Ireland, there were tensions between the Irish Women’s Franchise League – the local militant organization founded by Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington (1877-1946) and Margaret Cousins (1878-1954) – and the WSPU when the latter began to operate in that country, especially in Belfast from 1913. These tensions were due to differences regarding appropriate levels of militancy, territoriality and nationalism.

Responses to the War↑

When war came in August 1914, the suffragettes and suffragists had still not achieved their aim, though Prime Minister Herbert Henry Asquith (1852-1928) had by then indicated that he regarded the female franchise as inevitable, albeit in the context of wider franchise reform. Arguably, the outbreak of the war delayed this development. It certainly created circumstances in which the suffragettes became less visible. Nonetheless, as scholars (perhaps most importantly Sandra Stanley Holton, June Purvis and Angela K. Smith, in the case of Britain, and Margaret Ward, in the case of Ireland) have demonstrated, the suffragettes remained active even as the war posed quandaries for them, quandaries which further fragmented an already fragmented movement.

Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst committed the WSPU to the war effort, in a strategy that has been described as “patriotic feminism” or “patriotic suffragism”.[2] They suspended militancy in response to the release of prisoners; embraced jingoistic rhetoric (The Suffragette became Britannia); supported recruitment and, later, conscription; insisted that women workers should enter war industries, most notably at the “Right to Serve” march of July 1915; and opposed labour unrest in these industries. Through this, they built a relationship with David Lloyd George (1863-1945) as minister of munitions and, later, prime minister. Christabel Pankhurst stated that “[i]t is the women who prevent the collapse of the nation while men are fighting the enemy”[3] and in return, she implied, they expected reward in the form of the female franchise. In November 1917, in anticipation of post-war, post-enfranchisement elections, they formed the Women’s Party.

Other British suffragists whose response to the war was, like the Pankhursts’, essentially nationalist, preferred to express this through voluntary work. This included those within the NUWSS who lent their support to initiatives such as the Scottish Women’s Hospitals, which provided medical aid in several allied countries, and the Women’s Service Bureau, which provided vocational training for those entering war industries. In Ireland, the Irishwomen’s Suffrage Federation formed the Suffrage Emergency Council to organize war support.

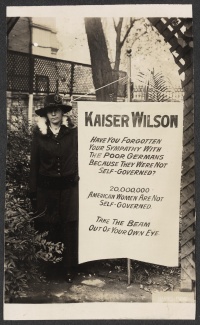

To some, this prioritisation of the war effort seemed an unwise muting, if not a traitorous abandonment, of the franchise cause. In the case of the WSPU, this stance, and Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst’s persistent autocracy, led to further departures and the foundation of the Suffragettes of the Women’s Social and Political Union (October 1915) and the Independent Women’s Social and Political Union (March 1916). In Ireland, the IWFL also rejected the Pankhurst approach. This opposition was expressed in a poster by Francis Sheehy Skeffington (1878-1916) that demanded “Votes for Women Now – Damn Your War” and in Hanna Sheehy Skeffington’s warning in the Irish Citizen, ten days into the war, that

They did not “roll up the map of suffrage” and their war-time campaigns included opposition to the Defence of the Realm Act, Regulation 40D, which re-introduced some elements of the notorious Contagious Diseases Acts of the 1860s.[4]

In the case of the Sheehy Skeffingtons, Irish nationalist sentiment and the belief that suffragism should come first were combined with pacifist and internationalist tendencies. That combination of pacifism and internationalism also constituted an important strand within British suffragette and suffragist responses to the war. This was evident in outright opposition to the war, or in support for a negotiated settlement, by figures such as Sylvia Pankhurst of the ELFS, Charlotte Despard (1844-1939) of the WFL, the Pethick-Lawrences of the United Suffragists, and amongst a constituency within the NUWSS. Such women expressed their stance in various ways. These included demonstrations of solidarity with the women of the Central Powers, sometimes delivered through the International Women’s Suffrage Alliance or contributions to its paper, Jus Suffragii. In April 1915, delegations from Britain and Ireland attempted to attend an International Congress of Women at The Hague, which had been convened to demand for an end to the war. The government prevented this, and British attendees were limited to three who did not have to travel from the United Kingdom. Many did, however, establish links to the International Committee of Women for Permanent Peace, which emerged from the congress. It was later re-named the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom.

Conclusion↑

The war ensured a widening of the male franchise in the United Kingdom and, in January 1917, an all-party committee recommended the simultaneous introduction of a limited female franchise. Lloyd George confirmed the government’s intention to deliver on this in March, and it became law through the Representation of the People Act the following February. This was the culmination of half a century of campaigning by suffragists and suffragettes, copper-fastened by women’s contribution to the war effort, which, as Nicoletta F. Gullace has stated, acted to “promote new ideas about gender and civic participation.”[5] These should not be understood as separate roots. Instead, the suffragists’ and suffragettes’ long campaign had helped to shape the nature of women’s war contribution, while their arguments did much to determine the ways in which that contribution was understood and rewarded.

William Murphy, Dublin City University

Section Editor: Jennifer Wellington

Notes

- ↑ The Suffragette, 18 April 1913.

- ↑ Purvis, June: Emmeline Pankhurst. A Biography, London 2002, p. 268; Smith, Angela K.: Suffrage Discourse in Britain during the First World War, Burlington 2005, pp. 21-50.

- ↑ Purvis, Emmeline Pankhurst 2002, p. 270.

- ↑ Ward, Margaret: Rolling up the Map of Suffrage, in: Ryan, Louise/Ward, Margaret: Irish Women and the Vote. Becoming Citizens, Dublin 2007, pp. 136-153; Ryan, Louise: Winning the Vote for Women. The Irish Citizen Newspaper and the Suffrage Movement in Ireland, Dublin 2018, pp. 89-128.

- ↑ Gullace, Nicoletta F.: The Blood of Our Sons. Men, Women and the Renegotiation of British Citizenship during the Great War, New York 2002, p. 2.

Selected Bibliography

- Gullace, Nicoletta F.: 'The blood of our sons'. Men, women, and the renegotiation of British citizenship during the Great War, New York 2002: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Holton, Sandra Stanley: Suffrage days. Stories from the women's suffrage movement, London; New York 1996: Routledge.

- Pugh, Martin: The Pankhursts, London 2001: Allen Lane.

- Purvis, June: Emmeline Pankhurst. A biography, London 2002: Routledge.

- Ryan, Louise: Winning the vote for women. The Irish citizen newspaper and the Suffrage Movement in Ireland, Dublin 2018: Four Courts Press.

- Ryan, Louise / Ward, Margaret: ‘Rolling up the map of Suffrage’. Irish suffrage and the First World War: Irish women and the vote. Becoming citizens, Dublin 2007: Irish Academic Press, pp. 136-153.

- Smith, Angela K.: Suffrage discourse in Britain during the first World War, Burlington 2005: Ashgate.