Introduction↑

The First World War saw the rise of state-organized propaganda as a new weapon in war. It enforced the coordination, professionalization, and systematization of intelligence work as well as censorship, news manipulation and propaganda work in a previously unknown scale. New institutions and networks were established during the entire war period, eager to engage in what Harold D. Lasswell (1902-1978) identified as the four objectives of war propaganda: 1. To mobilize hatred against the enemy, 2. To preserve the friendship of allies, 3. To preserve the friendship and, if possible, to procure the cooperation of neutrals, 4. To demoralize the enemy.[1]

On 6 August 1914, President Yuan Shikai (1859-1916) declared China’s neutrality. However, due to Germany’s colonial and economic presence, the conflict quickly arrived in China. Great Britain began spreading anti-German propaganda and acted accordingly, supported by its ally Japan, which grasped the chance to seize the German possessions in Shandong Province but abstained from overtly anti-German activities afterwards. Allied propaganda in China was largely the product of Great Britain, France and the USA, throughout the war challenged by Germany’s “friendship propaganda.” The propaganda was subtle and intriguing, later also direct and uninhibited. From manipulating information to spreading lies and accusations, it spoke through pamphlets and speeches, newspapers and pictorials, newsreels and films. Propaganda included “cultural work” and was carried out through private communication and social networks.

The analysis of foreign wartime propaganda in China is a desideratum. Scholars of propaganda have been working on specific aspects, effects or nations, but usually with a focus on Europe and little reference to non-European states such as China. Reasons for this lack of interest may be found in the complexity of propaganda work in China, deriving from the fact that the general conditions were remarkably different from those in Europe. Although a colonial power, Germany was not the most threatening enemy but had the positive reputation of being a strong and powerful nation with comparatively little political and military ambitions in China. Besides, both Japan and China had chosen Germany as a model for state and military reforms, looking at it with respect. China was more uncomfortable with France and Russia, and especially with the alliance of Japan and Great Britain. Consequently, “unofficial opinion in the country, where it was not indifferent, tended to favor Germany rather than her enemies.”[2] Equally problematic was the fact that the allied powers hardly developed a unified propaganda strategy: instead, their relationship was often determined by post-war considerations, competition, conflict and distrust.

This article provides a general overview with an emphasis on the dominating German–British conflict in China. It begins with an introduction to the most relevant international press and information networks, and the sections that follow characterize the intensification of propaganda work in the three major periods: (1) Information warfare until 1917, (2) Propaganda boom during the summer 1917, (3) American propaganda and promises, 1917-1919.

The International Press and Information Networks in China by 1914↑

In the decade before World War I, politics began to play an important role in China’s world of newspapers.[3] Official governmental newspapers were competing with both a rising reform press that had begun to spread from the foreign concession areas into the hinterland and a largely private press market especially in Shanghai, consisting of tabloid papers, literary magazines, and politically oriented newspapers.[4] Published in Shanghai were also the influential Chinese daily newspaper Shenbao and the magazine Dongfang zazhi (Eastern Miscellany), which from August onwards and throughout the entire period devoted large space to the war.[5]

The treaty ports had always been sheltered zones for a collaborative and competitive Sino-foreign media landscape. All powers published their representative newspapers in these ports, while the British Reuters News Agency, operating in China since 1859, largely monopolized the supply of international news. Reuters opened its Asia headquarters in Shanghai in 1871 and, based on agreements with the French Agence Havas and the German Wolffs Telegraphisches Bureau, covered and controlled an area that after World War I included the Straits Settlement, China, Manchuria, Korea, Japan, the Philippines, Borneo, and the Dutch East Indies. Also strongly engaged was the Japanese press.[6] Reflecting the Anglo-Japanese Alliance, signed in 1902 to last until the early 1920s, an influential English-language press network had been established.[7] One specific network was related to the activities of John Russell Kennedy (1861-1928), who in 1913 had become president of the Japan Times. He set up the Kokusai News Agency, which in February 1914 signed an agreement with Reuters and was the largest supplier of news to Chinese publications. In 1919, Kennedy would accompany the Japanese delegates to Versailles as a propagandist.

This Anglo-Japanese collaboration was not uncontested. In Germany, industrialists and politicians complained about one-sided documentation of German interests abroad, mostly blaming Reuters. In China, protest came for example from the English-language National Review (1909-1916), later subsidized by President Yuan Shikai himself.[8] American complaints in China were voiced by Thomas F. F. Millard (1868-1942) from Missouri, who founded the newspaper The China Press in Shanghai in 1911. Millard hired experienced journalists such as Carl Crow (1883-1945) and John Benjamin Powell (1886-1947), who shared his “generally anti-imperialist pro-Chinese view of China.” The China Press benefited from its close relationship with Dr. Wu Tingfang (1842-1922), China’s former Minister to America and premier. It attracted a large readership and in 1917 Millard founded Millard’s Review, a high-quality weekly journal. Due to its pro-Chinese and anti-Japanese stance, the three journalists’ work “was almost universally reproduced in translated form in the Chinese Press in Shanghai.”[9] Millard repeatedly complained about Reuters’ and Kokusai’s news manipulation and control of “international publicity” in Asia.[10] Another network refers to George Ernest Morrison (1862-1920), the former Times correspondent in Beijing, who in August 1912 had become a political advisor to the president of the Republic of China. Both Millard and Morrison would accompany the Chinese delegates to Versailles in 1919.

Information Warfare and China’s Struggle for War Participation↑

With the outbreak of war, Germany began to spread “in neutral countries the German version of the causes of the war, and the hostile intentions of its enemies.”[11] France and Great Britain acted quickly, though uncoordinated in the beginning.[12] In Paris, the “Maison de la presse” began operating in January 1916. The “Service de Propagande,” and especially the “Section Extrême-orientale” were responsible for disseminating material to China. In London, the War Propaganda Bureau, known as Wellington House, was established in early September 1914. Great Britain first concentrated on dismantling Germany’s international communication network – in September 1915 the last German Atlantic cables were cut.[13] In China, Great Britain had confiscated German possessions and ships in Hong Kong early on, and urged all British nationals to abandon business with German individuals and companies on 7 August 1914. On the same day, Japan was officially asked to assist in destroying the German navy in and around Chinese waters. Japan declared war on 23 August and on 7 November, supported by British troops and warships, defeated Germany’s colonial forces in Shandong Province. After the loss of the “model colony” (“Musterkolonie”), the closure of German schools and the Qingdao newspapers German propaganda activities and efforts to spread “German-ness” (Deutschtum) were severely reduced.

German propaganda did, however, continue and its main objective was to maintain friendly relations with China and prevent her from any war efforts on the allied side. For similar reasons, and throughout the war, German diplomats also engaged in secret negotiations with Japan, hoping to even win her as an ally against Great Britain.[14] Japan’s disturbingly ambivalent diplomatic navigation and calculated indifference did not escape G. E. Morrison’s observations while in Japan. In September 1916, he wrote that “Japan is acting in regard to Germany as a neutral power, and not as an enemy Power. Germans have every freedom to trade in Japan.”[15]

In China, German propaganda was effectively competing with the British dominated news services. As one observer noted, “German propaganda had skillfully magnified German successes and Allied losses, and in 1917 the average Chinese believed firmly that Germany would win the war.”[16]

The effectiveness of German propaganda was based on Germany’s positive reputation and a set of well-organized intertwined propaganda tactics. Germany transmitted news via the most powerful telegraphic transmitting station in the world at Nauen and the government affiliated Overseas Transocean Company (GmbH). Supported by neutral powers, “news were thus cabled to Asia via San Francisco and Guam to Manila and Shanghai. By May 1915, Transocean cabled 25.000 words monthly, approximately as much as Reuters.”[17] Germany’s most-renowned papers, Der Ostasiatische Lloyd and the Deutsche Zeitung für China (Hua De ribao) continued to be published in Shanghai. Other publications were The War, published three times a week in English, and the satirical magazine Wau-Wau. It was also reported that German buyers had acquired the Peking Gazette in October 1914.[18] The publication of the Chinese language newspaper Xiehebao (1910-1915) was terminated in June 1915.[19]

The German News Service was edited by “the notorious Dr. Fink,” whom the leading British newspaper in China, The North China Herald, made responsible for what it called the German “fiction factory.”[20] German papers promoted news regarding science, technology, and merchandize, and included messages of German power and war victories as well as examples of Sino-German friendship. Information was also spread through a semi-official network that included embassies, legations, consular offices, and branches of German banks and shipping companies. Several associations and clubs collaborated with China’s high-level officials and politicians. German propaganda also survived within the previously established structures of “German cultural work” (deutsche Kulturarbeit), e.g., in German missionary schools, primary and elementary schools, at Tongji University, and via student exchange.[21] In addition, clubs of neutral states provided space for pro-German activities, such as the YMCA in Shanghai. In 1915, the presentation of “German War Pictures” with English subtitles led to heated public debates and severe criticism.[22]

If many Chinese tended to believe in German news and war propaganda, it was also because it fitted into their general image of Germany as a strong militaristic nation. This notwithstanding, various options for China were negotiated within the public sphere.[23] Already in late 1914, the government signaled its willingness to participate in the war, while the publicist and reformer Liang Qichao (1873-1929) spoke of a “once-in-a-thousand-years opportunity” for the Chinese to renew their country and to regain national sovereignty.[24] The tone sharpened when Japan threatened China with the “Twenty-one Demands,” put forward in January 1915. China’s Foreign Ministry and the media began to push for China’s participation in the final peace conference as the only way to counter Japanese aggression. Chinese intellectuals and other elite members supported this official aim and soon rose in rebellion after Yuan Shikai agreed to sign “13 Demands” (25 May). Protests culminated into a new movement that characterized the awakening of China’s young generation. The medium of protest comprised periodicals and journals, which required less money and were not as closely watched as newspapers. The most influential group of intellectuals was associated with the popular magazine Xin Qingnian – La Jeunesse (New Youth), founded by Chen Duxiu (1879-1942) in Shanghai in September 1915. Their discussions on “national awakening,” with reference to science, democracy, socialism, and vernacular literature, initiated the New Culture Movement. Following Yuan Shikai’s death and the end of rigid censorship, a wide range of new journals and newspapers were published, especially in Beijing.[25] In early 1917, Xin Qingnian moved its headquarters to the capital. Attracted by Russia’s revolutions in February and October, China’s young intellectuals would soon start to promote Marxism and leftwing ideas.

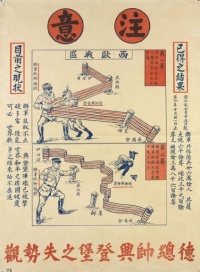

Meanwhile, in March 1915, the French Ministry of War had begun to secretly discuss the import of Chinese laborers.[26] In early November, China’s government informed Great Britain that it was prepared to go to war.[27] China’s claim was rejected again, this time because of Japanese intervention. Several months later, in August 1916, when the first group of Chinese laborers arrived in France, Great Britain not only began to negotiate its recruitment scheme with China, but also increased British propaganda efforts by establishing a War Propaganda Committee in Shanghai. The Committee’s main task was the nationwide distribution of millions of copies of war newssheets and pictorials that arrived from London. Among them was the newly created and government-sponsored pictorial Cheng Pao, which was published as a bi-weekly in Chinese and until 1919 distributed in millions of copies.[28] It was later described as very effective, and competed with the Japanese Shuntian Ribao and the French Ouzhan Bao.[29] The material from London was sent via the Chinese post office to Chinese officials, schools, and military officers.

By now, Wellington House had begun to engage in film propaganda and Reuters was sending 32,000 words a month to the treaty port. The North China Herald continued to stress the enemy’s atrocities in articles like “German Horrors in Africa,” though the British themselves were in doubt “that the Chinese were very interested in battlefield news from Europe.”[30] Moreover, despite the war and widespread propaganda, at least on the surface life within the treaty ports continued largely unchanged. John B. Powell, eager to start his career as a journalist for Millard’s China Press, remembered his arrival in Shanghai in late January 1917 as follows: “…I was surprised to find that the Germans still went about the city in complete freedom and safety, despite the fact that they were involved in war with both the British and French, who occupied a dominating position in the city.”[31]

Propaganda Boom: China’s War Entry in Summer 1917↑

Change came quickly after Germany’s declaration of unrestricted submarine warfare on 1 February 1917 had initiated a series of international protests: two days later, the USA gave up neutrality and cut diplomatic ties with Germany. On 4 February, President Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924) asked all neutral states to follow. China acted promptly and sent a warning on 2 February. The North China Herald complained about false and distorting news from German sources, while German propaganda attacked British recruitment of Chinese coolies, promising “them a life of misery and danger in the service of the British in Europe.”[32] The Ostasiatischer Lloyd also pointed out that “no intelligent Chinese will deny that Germany has been the most honest and sincere friend of China since it became involved in East-Asian policy.”[33] The pro-war faction, however, had won an important argument after the French ship SS Athos sank on 17 February 1917, with 543 Chinese workers on board in the Mediterranean, due to German submarine warfare. German diplomats tried to prevent the break of diplomatic relations at all costs, unsuccessfully offering Duan Qirui (1865-1936) 1 million dollars. [34]

China’s break-off of diplomatic relations on 3 March and widespread protest against Germany’s inhumane war policy encouraged the North China Herald to publish radical anti-German comments. One writer complained about the “Wolff Bureau issuing paid lies...,” ending with the words: “It’s worse than a lie, it’s German!” Another comment made clear that the word “German” stood now for “everything that is vile, treacherous and savage.”[35]

Meanwhile, Chinese voices with different interests had begun to make themselves heard within the Chinese public sphere, debating the pros and cons of China’s war participation.[36] While most of the intellectual elite supported China’s active war participation, President Li Yuanhong (1864-1928) hesitated and the reformers Kang Youwei (1858-1927) and Dr. Sun Yatsen (1866-1925) did their utmost to prevent China’s war entry. Kang sent several letters to China’s government, while Dr. Sun approached British Prime Minister Lloyd George and published the pamphlet Zhongguo cunwang wenti (The Question of China’s Survival) in 1917, written in cooperation with Zhu Zhixin (1885-1920). It was “extremely hostile to Great Britain,” considered “Germany to be less aggressive toward China than Russia”[37] and offered several arguments for China’s neutrality. German diplomats, some of whom had not left China, early approached Dr. Sun and offered him 2 million Chinese dollars to overthrow the Duan Qirui government. Sun accepted the offer and in June even sent a letter to President Wilson. By then, however, the question of war participation (canzhan wenti) was of only secondary importance, due to governmental conflicts and a political crisis that even saw the brief resurrection of the Qing Dynasty.

When America declared war on Germany on 6 April it also began to seriously participate in the propaganda war in China. Only a week later, President Wilson created the Committee on Public Information, led by the journalist George Creel (1876-1953). The so-called “Creel Committee” promoted U.S. participation in the war and was asked to promote the “correct” opinion of America in foreign countries. It did, however, also receive reports about German intelligence activities in China, written by American citizens living there.[38] These activities, which according to American journalist John B. Powell had so far been kept “well under cover,” became public on 23 April, when the well-known American missionary Dr. Gilbert Reid (1857-1927) was arrested “on a charge of libeling President Wilson.” Reid opposed China’s war entry and had “acquired control of the Peking Evening Post from its Chinese owner” in January 1917. Since the newspaper had been turned into an organ of German policy, Reid was arrested and by the end of the year deported to Manila.[39]

Under these circumstances, Great Britain increased its efforts and in May 1917 had the rights for film propaganda transferred to the war Propaganda Committee in Shanghai.[40] From September until the end of the war, the Committee received between one and two films a month for distribution in China, altogether twenty-six films and thirty-five official newsreels, which were exhibited in fifty-one places on a total of 593 occasions, but not necessarily positively received.[41]

The fact that China had to fight against German militarism and on the side of law and morality, grasp the chance to abolish the unequal treaties, and secure her seat at the peace conference, were arguments shared by the majority of China’s intellectual elite at that time.[42] However, China’s premier Duan Qirui was clearly more interested in first securing his power base through secret negotiations with Japan: in exchange for the “Nishihara Loans” he guaranteed Japan the former German possessions in Shandong Province and increased rights in Manchuria, thereby also reducing Japan’s opposition toward China’s war entry on the side of the Allies. On 14 August, pushed by Duan Qirui and without consulting the parliament, China declared war. German propagandists would later spread the message that Duan had received 7 million dollars from the Allies for this decision – Liang Qichao was said to have received 2 million.[43]

American Propaganda and Promises, 1917-1919↑

After China’s war declaration German publications were officially stopped and banned from circulation. In late 1917, when China had been assured of participating in the final peace conference, confiscation of German property started.[44] The North China Herald continued to promote patriotism, criticized German war lies, and referred to cruel German military operations such as those during the suppression of the Boxer Movement in 1900. British efforts also concentrated on detecting and identifying “Hun Propaganda,” which still came to Shanghai via Zürich, “being printed in four or five languages.”[45]

Ongoing pro-German agitation and “continued enemy activities” in China were largely attributed to pro-German sympathies among Chinese officials and a too relaxed enforcement of enemy restrictions. “Even if all the enemy subjects here were angels, we ought to fight them, not in a German way, but surely as hard as we can in a human way,” argued one commentator in the North China Herald.[46] In the eyes of many allied supporters in China, “deportation from the country of all German and Austro-Hungarian subjects offered the only remedy for this situation.”[47] Pressed for results, the Beijing Government issued its first regulations to prohibit trade with the enemy only on 17 May 1918.[48]

Meanwhile, American propagandists were successfully challenging British interests. Already in mid-1917, the American Minister to China, Paul S. Reinsch (1869-1923), had taken the initiative to recruit missionary volunteers to translate Wilson’s speeches into Chinese in order to distribute them to the press, and in pamphlet form.[49] His speech about the “Fourteen Points” (8 January 1918), in which he outlined his vision of the post-war situation by emphasizing free trade, open agreements, self-determination, and democracy immediately entered the Chinese press.[50] While the Chinese public enthusiastically embraced Wilson’s plan, Reinsch complained with other journalists in China to Washington that all information about America was transferred via Reuters and Kokusai, which meant that America’s war contribution was not adequately covered in the news. In order to compete with the British, Japanese, and French news services, which paid subsidies to the Chinese press to get their articles published, it was concluded that America needed its own news service in China. By June 1918, Reinsch obtained the necessary funds from Washington and on 10 September, Carl Crow was appointed to lead the China branch of the Committee on Public Information in Shanghai.[51] In fall 1918, the Chinese-American News Agency (Zhong-Mei) was established, and “by October, the agency was supplying news and articles to dozens of Chinese-language newspapers” (by 1919, around 300 in China).[52] Similar to American election campaigns, Crow employed various techniques, put into practice through hundreds of volunteer agents in China who were circulating photographs, posters, news summaries, newsreels, maps, etc. Most impressive was a bilingual collection of Wilson’s “War Addresses,” published by the Commercial Press, Shanghai, in late 1918.[53] The book became a bestseller and was used for English teaching in the classroom. When Germany agreed to the armistice on 11 November 1918, Wilson’s program for post-war reconstruction became even more popular in China.

In early 1919, the Allies’ constant complaints about China’s reluctance regarding her enemies bore fruit. To meet allied propaganda demands, President Xu Shichang released regulations regarding the liquidation of enemy property in late January, one day before the Chinese delegation’s formal presentation at the peace conference in Versailles on 28 January.[54] The repatriation of Germans and Austrians was organized in February/March, obviously to further strengthen China’s position at the peace conference. China was keen to see American propaganda put into practice and expectations were high, with many Chinese also actively spreading pro-Chinese propaganda in Paris. When China’s claim regarding the “Shandong Question” was finally officially rejected on 28 April, frustration culminated into protests on Beijing’s Tiananmen Square on 4 May 1919 and quickly spread throughout the country.[55] The so-called May Fourth Movement gave way to strong anti-Japanese and anti-Western expressions. Germany finally signed the treaty on 28 June; the Chinese delegation refused its signature.

Conclusion↑

Throughout the First World War, the foreign powers employed various forms of propaganda in China, constantly trying to inform and manipulate governmental and public opinion to side for or against China’s war participation. Although many aspects need to be analyzed in more detail and this article is far from being comprehensive, it should be sufficient to allow the following preliminary conclusion.

British Reuters and Japan’s Kokusai were dominating the transfer of international (war) news, challenged by Germany and later by the USA, Germany’s obvious success was astonishing, yet to a large extent, it was the result of its more positive image in China. Great Britain, on the other hand, was the main imperialist power in China, which had formed an alliance with Japan. When Japan revealed its imperialist ambitions by seizing Shandong Province and putting forward the “Twenty-one Demands,” it took responsibility for its highly negative image in China. Great Britain felt increasingly uncomfortable about its ally, but remained inactive on this issue. Until 1917, Great Britain and Japan prevented China from officially entering the war, while German propaganda successfully promoted a victorious image in China. However difficult the impact of Britain’s ever-increasing propaganda efforts may be to evaluate, constant critique and revelations about German war proceedings and strategies surely affected Germany’s reputation in China.

This was the situation when the USA joined the war and invited China to participate on the side of the Allies. China’s decision was motivated by post-war considerations and forced German propaganda into the underground. Almost simultaneously, America began to seriously engage in propaganda work, and news about the Russian Revolution entered public discourse in China.

The success of American propaganda was the result of enormous efforts and an overall message that not only went beyond accusations of war atrocities, but presented a vision that China was waiting for and could identify with. This vision, together with China’s reluctance for strict control of enemy subjects, challenged British propaganda, which aimed at the elimination of German business and existence in China and Asia. However, the fact that Germany was finally driven out of China, one may argue, was less the result of British efforts than that of American propaganda and its promises.

The year 1919 revealed the power of propaganda and the enthusiasm it could encourage, yet it also demonstrated its limits and dangers. People felt betrayed because President Wilson had failed to implement his “Fourteen Points,” which in China alone had been promoted nationwide and were studied for more than a year. The result was that new forms of anti-Japanese and anti-Western propaganda quickly emerged among students and workers. Foreign reactions varied, but the Japanese press, for example, reported that the strong anti-Japanese sentiment expressed in China was the result of American and British propaganda. Amidst this new propaganda warfare, people began to realize that China’s war efforts did not have a substantial effect on the status quo of Sino-Western relations. The transformation of Russia, therefore, provided an appealing new option for many frustrated Chinese intellectuals such as Li Dazhao (1888-1927), who in October 1918 had published an article on “The Victory of Bolshevism” in the popular magazine Xin Qingnian (New Youth). In this context, the declaration of the new Soviet government from 25 July 1919, must be considered as a highly effective propaganda coup: proposed was no less than the abrogation of all unequal and secret treaties signed between Tsarist Russia and China, as well as the relinquishment of all privileges, without compensation.[56] These were not hollow phrases but facts, and clearly, constituted a message that went beyond everything Western propaganda had promised.

Andreas Steen, Aarhus University

Section Editor: Guoqi Xu

Notes

- ↑ Lasswell, Harold D.: Propaganda Technique in the World War, New York 1927 [1938], p. 195.

- ↑ Pollard, Robert T.: China’s Foreign Relations 1917-1931, New York 1933 [1970], p. 8.

- ↑ See Nathan, Andrew J.: Chinese Democracy, New York 1985; and MacKinnon, Stephen R.: Toward a History of the Chinese Press in the Republican Period, in: Modern China, 23/1 (1997), pp. 3-32.

- ↑ Vittinghoff, Natascha: Unity vs. Uniformity: Liang Qichao and the Invention of a New Journalism for China, in: Late Imperial China, 23/1 (2002), p. 92. On the Chinese press, see Goodman, Bryna: Networks of News: Power, Language and Transnational Dimensions of the Chinese Press, 1850-1949, in: The China Review, 4/1 (2004), pp. 1-10; Wagner, Rudolf G.: Don’t Mind the Gap! The Foreign Language Press in Late-Qing and Republican China, in: China Heritage Quarterly 30/31 (2012), online: http://www.chinaheritagequarterly.org/features.php?searchterm=030_wagner.inc&issue=030 (retrieved 7 October 2015).

- ↑ A selection of articles is translated and reprinted in German in: Steen, Andreas: Deutsch-chinesische Beziehungen 1911-1927. Vom Kolonialismus zur Gleichberechtigung. Eine Quellensammlung, Leutner, Mechthild (ed.), Berlin 2006.

- ↑ See: Goodman, Networks of News 2004, pp. 1-10; Silberstein-Loeb, Jonathan: The International Distribution of News: The Associated Press, Press Association, and Reuters, 1848-1947, New York et al. 2014; and Basse, Dieter: Wolff’s Telegraphisches Bureau 1849-1933, Munich al. 1991.

- ↑ See O’Connor, Peter: The English-Language Press Networks of East Asia, 1918-1945, Leiden 2010.

- ↑ French, Paul: Through the Looking Glass. China’s Foreign Journalists from Opium Wars to Mao, Hong Kong 2009, p. 100.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 105.

- ↑ See in particular Chapter XI, International Publicity and the Far East (pp. 194-218), in: Millard, Thomas F.: Our Eastern Question – America’s Contact with the Orient and the Trend of Relations with China and Japan, New York 1916.

- ↑ Welch, David: Germany, Propaganda, and Total War, 1914-1918, New Brunswick 2000, p. 22.

- ↑ Sanders, M. L./Taylor, Philip: Britische Propaganda im Ersten Weltkrieg, 1914–1918, Berlin 1990, p. 22.

- ↑ Winkler, Jonathan Reed: Information Warfare in World War I, in: The Journal of Military History, 73/3 (2009), p. 848.

- ↑ See Hayashima, Akira: Die Illusion des Sonderfriedens. Deutsche Verständigungspolitik mit Japan im ersten Weltkrieg, Munich et al. 1982.

- ↑ Private letter from Morrison to H. A. Gwynne, 15 September 1916, in: Hui-min, Lo (ed.): The Correspondence of G. E. Morrison, volume 2, 1912-1920, Cambridge et al. 1978, pp. 555-556.

- ↑ Wheeler, W. Reginald: China and the World War, New York 1919, p. 82.

- ↑ See Evans, Heidi J. S.: The Path to Freedom? Transocean and German Wireless Telegraphy, 1914-1922, in: Historical Social Research 35 (2010), p. 217; see also, Winkler, Information Warfare 2009, p. 852; and Welch, Germany, Propaganda and Total War 2000, pp. 22-23.

- ↑ French, Looking Glass 2009, p. 109.

- ↑ Zhang, Shiwei: Tan Deguo ‘Xiehebao‘ zai Hua xuanchuan celue [The Propaganda Tactics of the German Newspaper ‘Concorde’ in China], in: Linyi Daxue Xuebao [Journal of Linyi University], 34/3 (2012), pp. 115-118.

- ↑ Carl Fink (1861-1943). See Propaganda in China, in: The North-China Herald, 1 February 1919, front page.

- ↑ Reinbothe, Roswitha: Kulturexport und Wirtschaftsmacht. Deutsche Schulen in China vor dem Ersten Weltkrieg, Frankfurt am Main 1992. On Germany’s propaganda network, see Welch, Germany, Propaganda and Total War 2000. See also Kirby, William: Germany and Republican China, Stanford 1984.

- ↑ German War Pictures at Y.M.C.A, in: The North-China Herald, 9 October 1915, p. 114; and 16 October 1915, p. 186-187.

- ↑ See Xu, Guoqi: China and the Great War. China’s Pursuit of a New National Identity and Internationalization, Cambridge 2005, pp. 81ff.

- ↑ Peking Gazette, 31 December 1914. See Xu, China and the Great War 2005, p. 83.

- ↑ Ting, Lee-hsia Hsu: Government Control of the Press in Modern China, 1900-1949, Cambridge, MA 1974, p. 51.

- ↑ Bailey, Paul: The Sino-French Connection and World War One, in: Journal of the British Association for Chinese Studies 1 (2011), p. 6.

- ↑ Xu, China and the Great War 2005, pp. 100ff.

- ↑ See Sanders, M. L.: Wellington House and British Propaganda in the First World War, in: The Historical Journal, 18/1 (1975), pp. 119-146; and also Schmidt, Hans: Democracy for China. American Propaganda and the May Fourth Movement, in: Diplomatic History, 22/1 (1998), p. 5.

- ↑ See Propaganda Work in China, in: The North-China Herald, 18 January 1919, p. 125. See also Secker, Fritz: Presse und geschäftliche Propaganda in China, in: Hellauer, Joseph: China. Wirtschaft- und Wirtschaftsgrundlagen, Berlin et al. 1921, p. 60.

- ↑ Schmidt, Democracy for China 1998, p. 5; German Horrors in Africa – A Terrible Record of Brutality, in: North-China Herald, 16 September 1916, pp. 587-588.

- ↑ Powell, John B.: My Twenty-Five Years in China, New York 1945, pp. 54-55.

- ↑ See German Communiques, in: North China Herald, 17 February 1917; Griffin, Nicholas J.: Britain’s Chinese Labor Corps in World War I, in: Military Affairs, 40/3 (1976), p. 104.

- ↑ Deutschland und China, Der Ostasiatische Lloyd, 23 February 1917, number 8, pp. 255-256. Reprinted in Steen, Deutsch-chinesische Beziehungen 2006, pp. 147-149.

- ↑ Steen, Deutsch-chinesische Beziehungen 2006, p. 119.

- ↑ It’s German, Letter to the Editor, in: North-China Herald, 10 March 1917, p. 524.

- ↑ See Xu, China and the Great War 2005, pp. 20-212.

- ↑ Bergère, Marie-Claire: Sun Yat-sen, Stanford 1998, p. 271. See also Kang Youwei’s telegram to president Li Yuanhong and Duan Qirui, April 5/6 1917, German translation in Steen, Deutsch-chinesische Beziehungen 2006, pp. 157-163.

- ↑ Matsuo, Kazuyuki: American Propaganda in China: The US Committee on Public Information, 1918-1919, in: The Journal of American and Canadian Studies, 14/2 (1996), pp. 19-42.

- ↑ Reid, Gilbert: Arrested, North-China Herald, 28 April 1917, p. 169. See also Reid’s articles: Shall China Enter the War?, in: The Journal of Race Development, 7/4 (1917), pp. 499-507, and The International Institute of China, in: The Open Court 12 (1929), pp. 705ff. See also Powell, John B.: My Twenty-Five Years in China, New York 1945, p. 38.

- ↑ On British film propaganda see Sanders, Britische Propaganda im Ersten Weltkrieg 1990, pp. 107-109, and Reeves, Nicholas: Film Propaganda and Its Audience: The Example of Britain's Official Films during the First World War, in: Journal of Contemporary History, 18/3 (1983), pp. 463-494.

- ↑ Reeves, Film Propaganda 1983, pp. 476-479.

- ↑ See Xu, China and the Great War 2005, pp. 204-212; see also Li Dazhao’s article: Many Problems after the break of Sino-German Diplomatic Relations, in: Jiayin Rikan, 5 March 1917, reprinted in: Steen, Deutsch-chinesische Beziehungen 2006, pp. 149-151.

- ↑ German Propagandism, in: North-China Herald, 19 January 1918, p. 142.

- ↑ Steen, Deutsch-chinesische Beziehungen 2006, p. 124.

- ↑ German Revenge, in: North-China Herald, 12 January 1918.

- ↑ German Propagandism, North-China Herald, 19 January 1918, p. 142.

- ↑ Pollard, China’s Foreign Relations 1933, p. 43.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Manela, Erez: Wilsonian Moment: Self Determination and the International Origins of Anticolonial Nationalism, Cary 2007, p. 101.

- ↑ Manela, Erez: Imagining Woodrow Wilson in Asia: Dreams of East-West Harmony and the Revolt against Empire in 1919, in: The American Historical Review, 111/5 (2006), p. 1336. See also the Shanghai newspaper Shibao, 11 January 1918.

- ↑ Manela, Wilsonian Moment 2007, p. 100.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 101. Also O’Connor, English-Language Press Networks 2010, p. 141.

- ↑ Manela, Wilsonian Moment 2007, p. 102. Probably based on the volume, War Addresses of Woodrow Wilson, with an Introduction and Notes by Arthur Roy Leonard, Boston et al. 1918.

- ↑ Published later in the Zhengfu Gongbao (Government Journal), 20 March 1919, reprinted in Steen, Deutsch-chinesische Beziehungen 2006, p. 183.

- ↑ For a detailed account of the events see Tse-Tsung Chow’s classic study The May 4th Movement: Intellectual Revolution in Modern China, Cambridge, MA et al. 1960.

- ↑ On foreign attitudes and reactions see Chow, The May 4th Movement, pp. 197-214.

Selected Bibliography

- Bailey, Paul: The Sino-French connection and World War One, in: Journal of the British Association for Chinese Studies 1, 2011, pp. 1-19.

- Bruntz, George G.: Allied propaganda and the collapse of the German empire in 1918, Stanford; London 1938: Stanford University Press; H. Milford; Oxford University Press.

- Chow, Tse-tsung: The May 4th movement. Intellectual revolution in modern China, Cambridge; London 1960: Harvard University Press.

- Evans, Heidi J. S.: 'The path to freedom'? Transocean and German wireless telegraphy, 1914-1922, in: Historical Social Research 35/1, 2010, pp. 209-233.

- French, Paul: Through the looking glass. China's foreign journalists from Opium Wars to Mao, Hong Kong 2009: Hong Kong University Press.

- Goodman, Bryna: Networks of news. Power, language and transnational dimensions of the Chinese press, 1850-1949, in: The China Review 4/1, 2004, pp. 1-10.

- Griffin, Nicholas J.: Britain’s Chinese Labor Corps in World War I, in: Military Affairs 40/3, 1976, pp. 102-108.

- Hayashima, Akira: Die Illusion des Sonderfriedens. Deutsche Verständigungspolitik mit Japan im ersten Weltkrieg, Munich 1982: Oldenbourg.

- Hsu Ting, Lee-hsia: Government control of the press in modern China, 1900-1949, Cambridge 1974: Harvard University Press.

- Lasswell, Harold D.: Propaganda technique in the World War, New York 1927: Kegan Paul.

- Lo, Hui-min (ed.): The correspondence of G.E. Morrison, 1912-1920, volume 2, Cambridge; New York 1976: Cambridge University Press.

- MacKinnon, Stephen R.: Toward a history of the Chinese press in the Republican period, in: Modern China 23/1, 1997, pp. 3-32.

- Manela, Erez: The Wilsonian moment. Self-determination and the international origins of anticolonial nationalism, Oxford; New York 2007: Oxford University Press.

- Matsuo, Kazuyuki: American propaganda in China. The U.S. Committee on Public Information, 1918-1919, in: The Journal of American and Canadian Studies 14/2, 1996, pp. 19-42.

- Millard, Thomas F.: Our Eastern question. America's contact with the Orient and the trend of relations with China and Japan, New York 1916: Century Co.

- Niu, Haikun: Dewen Xinbao yanjiu 1886-1917 (A Study of 'Der Ostasiatische Lloyd' 1886-1917), Shanghai 2012: Jiaotong University Press.

- O'Connor, Peter: The English-language press networks of East Asia, 1918-1945, Leiden 2010: Brill.

- Pollard, Robert Thomas: China's foreign relations, 1917-1931, New York 1933: Macmillan.

- Powell, John Benjamin: My twenty-five years in China, New York 1945: The Macmillan Company.

- Reeves, Nicholas: Film propaganda and its audience. The example of Britain's official films during the First World War, in: Journal of Contemporary History 18/3, 1983, pp. 463-494.

- Reinbothe, Roswitha: Kulturexport und Wirtschaftsmacht. Deutsche Schulen in China vor dem Ersten Weltkrieg, Frankfurt a. M. 1992: Verlag für Interkulturelle Kommunikation.

- Sanders, Michael / Taylor, Philip M.: British propaganda during the First World War, 1914-18, London 1982: Macmillan.

- Sanders, M. L.: Wellington House and British propaganda during the First World War, in: The Historical Journal 18/1, 1975, pp. 119-146.

- Schmidt, Hans: Democracy for China. American propaganda and the May 4th movement, in: Diplomatic History 22/1, 1998, pp. 1-28.

- Secker, Fritz: Presse und geschäftliche Propaganda in China, in: Hellauer, Josef (ed.): China, Wirtschaft und Wirtschaftsgrundlagen, Berlin 1921: Walter de Gruyter & Co, pp. 49-63.

- Shiwei, Zhang: Tan Deguo ‘Xiehebao‘ zai Hua xuanchuan celue (The propaganda tactics of the German newspaper ‘Concorde’ in China), in: Linyi Daxue Xuebao (Journal of Linyi University) 34/3, 2012, pp. 115-118.

- Silberstein-Loeb, Jonathan: The international distribution of news. The Associated Press, Press Association, and Reuters, 1848-1947, Cambridge; New York 2014: Cambridge University Press.

- Steen, Andreas: Deutsch-chinesische Beziehungen 1911-1927. Vom Kolonialismus zur 'Gleichberechtigung'. Eine Quellensammlung, Berlin 2006: Akademie Verlag.

- Vittinghoff, Natascha: Unity vs. uniformity. Liang Qichao and the invention of a 'new journalism' for China, in: Late Imperial China 23/1, 2002, pp. 91-143.

- Welch, David: Germany, propaganda, and total war, 1914-1918. The sins of omission, New Brunswick 2000: Rutgers University Press.

- Wheeler, W. Reginald: China and the World War, New York 1919: Macmillan.

- Winkler, Jonathan Reed: Information warfare in World War I, in: The Journal of Military History 73/3, 2009, pp. 845-867.

- Xu, Guoqi: China and the Great War. China's pursuit of a new national identity and internationalization, Cambridge 2005: Cambridge University Press.