Introduction↑

Since seminal works by North American (John Godfrey, Martin Fine, Richard Kuisel), French (Patrick Fridenson) and German historians (Gerd Hardach) in the 1970s, which focussed on the industrial mobilisation (predominantly armament industries) and economic goals of the war (Georges Soutou), historical research on war economies has shifted to studies on social actors (employers’ associations, women and colonial workers, bankers), strategic sectors (chemical industries, coal, shipping) and consumer industries (textile, alimentation), as well as banking and War Finance. There has also been a shift from national scale studies focussing on politics (i.e. expansion of the state) at the macro or micro-levels, to regional and local-level case studies as well as biographies of key actors like Albert Thomas (1878-1932) or Louis Loucheur (1872-1931). Nevertheless, some issues remain under-researched, such as war profits or the role of international trading companies in supplying industries.

The concept of war economy encompasses that of economic mobilisation and must be distinguished from war effort. War is a shock that affects capital, labour, production, markets, flows and networks through a disorganisation/reorganisation process. At first, in the summer of 1914, growing international tensions and the declaration of war disrupted markets (foreign trade and finance), caused a credit crisis (bank runs, debt moratorium), and suspended the convertibility of the French currency (Franc) into gold. General mobilisation disrupted the national economy, causing the freezing of industries and agriculture, huge unemployment, shortages, and rising prices. At the same time, all resources had to become war-oriented; the military front required growing quantities of weapons and munitions, whilst the needs of civilians on the home front had to be met in order to mobilise capital, labour, science, and technology.

First, in the French historical context, a total war implies increased state controls leading to political, economic and social tensions: military versus civilian priorities, exceptionality versus normalcy, and short term versus long term visions. War economy is as much an economic war as a time of experimentation for peacetime.[1]

Three issues will be discussed here. First, what role did the different actors play? In order to answer this, one must first bear in mind that war erases boundaries between military and civil, public and private, and that the role of the state changes and expands during war: the state makes war, but war makes the state. Regarding the role of the state, how did the French “concerted economy” differ from the German economic model (authority of the military high commandment) and the British “statist-corporatist” model? Furthermore, because the state cannot be reduced purely to governmental actions, i.e. the executive power, an examination into the role of parliament and administration is also necessary. Second, the balance between the principles of a market-based economy and that of dirigisme (étatisme is a polemic word used to condemn it), also referred to as “organised capitalism”, “organised liberalism”, or “mixed economy”, resulted from a tension between pragmatism and ideology. What part did these principles play? Third, how efficient was the organisation of the war economy and what were its long-term consequences?

Thus, we shall examine four key elements: (1) the factors of and the pace at which the war economy was established; (2) features of the state interventions; (3) the role of capital and labour; and lastly, (4) the impossible “return to normalcy” after the war.

Setting up the War Economy: Chronology and Factors↑

During the first ten/eleven months of war, disorganisation and improvisation prevailed. The headquarters sometimes signed contracts directly with industrialists, which weakened government authority. From May/July 1915 until December 1916, the government took back control. New administrative bodies were launched, increasing the efficacy of the war machine. From 1917 onwards, state interventions helped to consolidate French connections with interallied economic organisations.

The Economic Needs and Constraints of a Long-lasting War↑

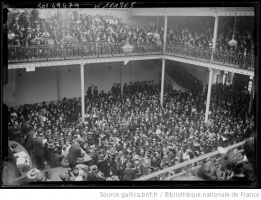

When war broke out in August 1914, long-term industrial mobilisation was not foreseen. The 1912 Plan de mobilisation was based on limited stocks and companies supplying production for military needs, namely a few public-owned arsenals and private armament firms. This soon appeared unrealistic. On 20 September 1914, the Minister of War Alexandre Millerand (1859-1943) convened the most prominent industrialists to organise armament production. He requested the production of 100,000 shells per day, instead of 13,000. This Conférence de Bordeaux launched the beginning of the industrial mobilisation, which faced five issues.

1) The disorganisation of mobilisation caused a sudden decrease in transport and in production, creating industrial and agricultural shortages. Additionally, the German army occupied ten départements either partially or totally, depriving the country of major resources, including 75 percent of coal, 80 percent of iron ore and cast-iron, 80 percent of worsted wool, 90 percent of flax spinning and linen, and a large part of sulphuric acid and superphosphates. Furthermore, the railway system was completely disorganised.

2) Structural dependencies. The chemical industry either depended on massive imports of nitrates and phosphates, or was underdeveloped due to dependence on German imports and patents. The shortage of nitrates and sulphuric acid hindered the production of powder and explosives. War also revealed French dependence on petroleum imports. Submarine warfare worsened the shortage of ships and cargo vessels.

3) Mobilisation caused labour force shortages, removing 63 percent of the total active male population throughout the war. After a few weeks, the government allowed 500,000 workers to return from the front to armament factories and by July 1915, just before the Dalbiez Law (August 1915) that regulated mobilisation, metallurgy had 82 percent of its pre-war labour force back and 66 percent in the chemical industries (100 percent and 93 percent respectively by January 1916).[2] In 1918, military workers represented 29 percent of the 1.7 million workers in the armament industry, while women made up 25 percent, male civilians (teenagers, older men and refugees from the occupied territories) made up 33 percent, and colonial and Chinese labourers constituted 4 percent.

4) Despite some large production programmes, growing military needs led to some dramatic shortages of munitions and cannons, particularly in autumn 1914 and November 1916. The question of whether military strategy should be adapted to productive capacities or vice versa, caused opposition between Minister of Armament Louis Loucheur and General Philippe Pétain (1856-1951) in the summer of 1917.

5) Ideological constraint was strong. There was the will to preserve liberal principles as far as possible. For every government – even for socialist ministers – private ownership and profit were not questioned.

At the International Level: British Pressure and Interallied Cooperation↑

From November 1915, France relied on British imports (food, coal, steel, iron) and the British navy as well as neutral merchant marines. The British government forced Paris to set up restrictions and to centralise demands.

After the Interallied Economic Conference in Paris in June 1916 and the addition of the USA to the war in April 1917, economic interallied cooperation was developed for food supply (December 1916), raw materials (August 1917), and shipping (Allied Maritime Transport Council, December 1917). This reinforced the need for centralisation, planning, requisitions and price controls. Hence, the creation of “Consortia” and many executive committees (comités interministériels) led to detailed programmes of needs and the general requisition of ships (February 1918).

In 1918, pressure from America for new organisations (Interallied Council for War Purchases and Finance, Armament and Munitions Council, and Food Council) converged with the French desire to promote an economic union of the Allies and they obtained an extension of the “executives” system for sixteen commodities like wool, petroleum, and chemicals.

The French Promoters of “Organised Capitalism”↑

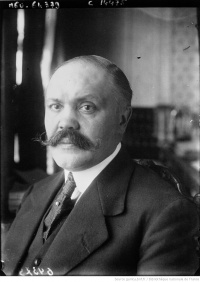

There was a French “ideology of industrial mobilisation”[3] and, more broadly, of economic organisation for wartime and peacetime. This was promoted by three ministers (alongside their main collaborators): Albert Thomas, Louis Loucheur and Etienne Clémentel (1864-1936). Despite government instability and ideological differences, their tenures gave a certain continuity to the French economic policy.

Albert Thomas, a socialist representative, was first entrusted with organising the technicalities of railways and war factories. He was appointed undersecretary of state for artillery and military crews (renamed artillery and munitions in October 1915) within the Ministry of War in May 1915, and in December 1916 he became minister for armament and war productions. Thomas expressed his vision, and that of his collaborators including the economist François Simiand (1873-1935) and the sociologist Maurice Halbwachs (1877-1945), of the war economy in speeches, the most famous of which was given at the Schneider factories in Le Creusot in April 1916.[4]

An engineer trained at the Polytechnique in Paris and an industrialist in electrical equipment and construction, Louis Loucheur was first appointed undersecretary for war productions under Thomas’ direction in December 1916. When Thomas was ousted, due to the rupture of the Union sacrée, Louis Loucheur replaced him as minister of armament (September 1917). Many of his collaborators were engineers. After the Armistice, from November 1918 to January 1920, he became minister of the industrial reconstruction (Reconstitution industrielle).

Trained as a notary, a representative from the parti radical and the mayor of Riom, Etienne Clémentel was previously minister of colonies (1905-1906) and of agriculture (1913). As the minister of commerce and industry for four years (November 1915-November 1919), he developed his vision alongside captain Henry Blazeix (1869-?), an engineer and chief of the Technical Services,[5] in two famous reports from 1917 and 1919.[6] He selected Jean Monnet (1888-1979) to represent his department at the interallied organisations in London.

For Thomas and Clémentel, the war was an opportunity to experiment with the organisation (rationalisation) of capitalism. The “spirit of war” put an end to individualism with the call for employers to organise and join forces, named “la poussière patronale” (employers’ dispersion) by Clémentel. Trade unions had to collaborate with business organisations thus renouncing the class struggle. The state coordinated and supervised private firms through concertation and controls, encouraging them to modernise production, to stimulate their “spirit of initiative”, and, for Clémentel, to conceive of national planning. After 1918, war experimentation continued and was developed (but only for a short time, according to Loucheur), as was the interallied economic union, a policy to limit German economic hegemony in Europe.

The End of the Liberal Era? Growing State Intervention↑

Despite the nuanced nature of France's pre-war liberalism, the unprecedented increase in state intervention is evidenced by the increase in national income used on public expenditure, which was 10 percent in 1913 and 53.5 percent in 1918 – similar to Germany but much higher than other countries.[7] This was further evidenced through increased constraints, such as on centralisation, controls, taxation, requisition, and public ownership. There was also expansion and reorganisation of the executive power and public administration.

Constant Expansion and Reorganisation of the State↑

The main ministries were constantly growing and reorganising. New ministries were also created, such as for supply and armament in December 1916 and industrial reconstruction in November 1918, alongside new undersecretaries and no less than 281 “committees” or “commissions”. This bureaucratic inflation or “state exuberance”[8] was topped off by the development of private administrations, set up by employers’ organisations such as professional unions and associations of victims of war and military occupation (associations de sinistrés).

The undersecretary for armament within the Ministry of War (May 1915) was created due to the multiplication of services within the Direction de l’Artillerie and the political power’s desire to take back control on military contracts. Albert Thomas oversaw the creation of many services, sections, and departments (directions), such as Industrial Service, Department of Chemical Warfare Equipment, and Labour Service in June 1915. This led to the transformation of the undersecretary into a ministry in December 1916, with two corresponding undersecretaries for war productions and inventions. Similarly, from 1916, Interallied and Technical Services were developed within the Ministry of Trade.[9]

There was no rationalisation of the state. Each critical issue (labour, food supply, raw materials, etc.) raised issues of shifting jurisdiction and overlapping competences; the case of the undersecretary for the merchant marine is exemplary. From October 1916, tensions grew between Clémentel (Ministry of Trade) and Loucheur (armament and later industrial reconstruction), regarding the distribution of raw materials between war and civil industries. This was one reason why inter-ministerial committees were created.

As a result of the growing power of the government and administration and despite parliamentary commissions remaining very active, technocrats gained power at the expense of parliament.

Industrial Policies↑

By 1918, the state had further economic responsibilities, such as planning, buying, distributing, financing, chartering, and producing. However, a complete reversal occurred in the armament industry between private and public. While in 1914 three quarters of the 50,000 armament industry workers were employed by state-owned arsenals, by 1918 this had fallen to only 18 percent of the 1.7 million workers[10]. Since the Conférence de Bordeaux, industrialists had been forced to organise. This took shape as twelve regional groups, whose leaders – the largest companies – were responsible for sharing out materials, distributing contracts, and coordinating production between (large) contracting firms and (small) subcontractors. During the regular conferences between the Ministry of Armament and these leading companies, war production programmes were shared and adjusted to actual industrial productive capacities.

The government provided raw materials, workforce, transport priorities and, in case of urgent investments, long-term advances to contracting companies. In return, from summer 1915 onwards, technical controls on companies’ production and workforce were developed, including authorisations for recruiting military workers and supervision over working conditions and salaries. A “Contracts’ Commission” was created on 3 September 1915 to control cost prices and contract terms (a general contracts revision was almost planned). The giant public-owned arsenal in Roanne (1917) was built to compete with the private armament industry and to create a public model of industrial and social modernity. It was a failure, but industrial mobilisation was successful and France exported arms to the Allies.

As for civil industries, Clémentel used the threat of civil requisition (law of 18 June 1917) to moderate prices, fight speculation, and limit war profits. He also launched a “national shoe” programme to transform military surplus leather into civilian shoes sold at state fixed prices.[11] He also attempted to force manufacturers to join consortia, which were joint-stock companies required to repurchase all raw materials bought by the state and resell them to their members at a price set by the Ministry of Trade. The first consortium was created for American cotton in October 1917. One year later, there were “nearly fifty consortia either established or about to be established”.[12] Nevertheless, the consortia were created very late and were far from widespread; many raw materials (such as wool or flax) were not included.

The maritime transport policy was fairly hesitant. After a few ship requisitions, demands became centralised through a committee in February 1916 and a licencing system and control on freight rates were established in April 1916. Nevertheless, by July 1916, two-thirds of commercial ships had been requisitioned. Due to the dramatic shipping crisis and creation of the Allied Maritime Transport Council, the general requisition took place in February 1918 – one year after the United Kingdom and two years after Italy. In order to rebuild shipping capacities, the state became the sole shipowner and charterer by March 1918, buying or building every ship.[13]

There were also long-term industrial policies. In armament industries, the government actively promoted mechanisation, Taylorism (1915) and standardisation (Commission permanente de standardisation, June 1918). The Department of Inventions (Direction des inventions) developed armament innovations, such as poison gas, tanks, and aircraft. The first project for a public scientific research office was launched. In order to create a French dyes industry to free France from German imports, a few companies, including Kuhlmann, were asked to form a syndicate fully supported by the government. Consequently, the National Dyes Company was founded between April and November 1916.[14]

A coal policy emerged in July 1917 and the Bureau national des charbons centralised the distribution of all coal, both French requisitioned and British imported, across seven categories of consumers and divided into regions. Priority was given to war industries and railways. However, the coal shortage led to an increase in hydroelectric power plants from 1916 and the idea to nationalise part of the hydroelectric production emerged post-war.

Social Policies↑

The war period saw the intensification of production, suspension of labour legislation (maximum working time and suspension of striking rights for mobilised workers from July 1915), and rising costs of living. The resulting social tensions led to increasing strike action from the end of 1916 and even more in 1917 and 1918. Hence, the government tried to appease industrial relations.

While promoting Taylorism in armament factories, Albert Thomas encouraged manufacturers to develop industrial welfare, such as canteens and medical services, as well as protections for women workers (providing nurseries, breastfeeding rooms, and “lady superintendants”). Thomas also created a “Committee of Female Labour” (April 1916) to make enquiries and recommendations. The principle of “equal pay for equal work” remained nevertheless unfulfilled, despite the legal salary range of January 1917.

In armament industries, minimum wages, conciliation procedures, and arbitration became mandatory from January 1917, as were shop stewards from June that year.

Financial and Tax Policies↑

In France, war finance was mainly based on public short-term debt (Bons de la Défense nationale) and four long-term loans (1915-1918). The government had a quasi-monopole on security issues. Banks were required to keep a large quantity of Bons de la Défense nationale in their assets. Big deposit banks organised the issuing of state long-term loans, acted as underwriters, and sold bonds to their clients. Banking supervision was limited to exchange control.

The state also addressed deficiencies of the banking system that had already been criticised pre-war, creating the Banques Populaires (1917) to help finance small business, and the Centres de Chèques postaux (CCP).

Furthermore, new taxes were established to address two main issues of social justice rather than to ease war financing. First, the progressive war excess profit tax (Contribution extraordinaire sur les bénéfices supplémentaires et exceptionnels de guerre) was established on 1 July 1916. Second, the old direct taxation system (“les quatre vieilles”) was replaced by the progressive global income tax (voted on by MPs in 1914 but not by the senate until July 1917) and the graduated income tax (e.g. on industrial and commercial profits).

The Role of Capital and Labour↑

The war economy relied on constant concertation between public authorities and private economic agents.

The balance of power between state and industrialists mostly favoured the latter. Taking advantage of the urgency of requirements, manufacturers imposed their own prices and conditions in military contracts, especially during the first year of war. After August 1915, although they consented to lower prices, manufacturers were reluctant to cooperate with enquiries into their costs. They avoided financial penalties by negotiating contract amendments on delivery times or quantities. Many delivered greater quantities than agreed. To secure investments and profits, manufacturers often requested regular orders or consideration of a higher capital depreciation in cost prices and profit calculations. As for the declaration of war excess profit, fraud and delays were very common, making the collection rate of this tax very low.

Due to the centralisation of economic decisions, being close to political power became a strong advantage for economic competition. Public and private interests became intertwined. Larger companies and employers’ organisations held key positions, such as the Comité des Forges and the Union des Industries Minières et Métallurgiques (UIMM), as well as the powerful ACRAIRE (Association centrale pour la reprise de l’activité industrielle dans les régions envahies), which was founded in 1915 by industrialists across the invaded territories to encourage economic recovery.

As long as the Union sacrée continued, trade unions, especially the CGT (Confédération Générale du Travail), accepted sacrifices. From 1917, the CGT accepted Taylorism, provided that workers could negotiate timing and pay. But the Union sacrée fell apart in 1917, with strikes for higher pay, rights for women workers, and better working conditions playing a very important role. In the garment industry, the Midinettes’ strike in Paris (May 1917) was a very new phenomenon. Peace slogans appeared in 1918. Most strikes were spontaneous and female workers often played a major part.

Post-war: The Impossible “Return to Normalcy”↑

During the last months of war and after the Armistice, Clémentel promoted the continuation of an organised economy in peacetime, at both national and international levels.

Clémentel campaigned for the continuation of interallied organisations as an “Allied economic union”, becoming an “economic weapon” against Germany. But President Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924) opposed this proposal in September 1918. Instead, the International Chamber of Commerce was born in Paris in June 1920.

Clémentel also promoted the organisation of French capitalism in a report to President Georges Clemenceau (1841-1929) in March 1919; a large Ministry of Economy was to be created to plan a national economy in concertation with employers’ organisations and trade unions. Companies were envisioned as merging into large corporations and uniting into cartels, and industrial rationalisation, standardisation, and mechanisation were to be widespread. Some of these ideas were implemented. The twenty-one employers’ federations formed a national business organisation, the CGPF (Confédération Générale de la production française), in March 1919 (the word “patronat” was avoided). Furthermore, the 160 Chambers of Commerce gathered into seventeen economic regions in April 1919, the Ministry of Trade was re-organised into five departments in October that year and a National Economic Council was established in 1924.

November 1919 saw the electoral victory of the political right, promoting a “return to normalcy”, defeating Clémentel. Nevertheless, the legacy of the war, specifically the increased state economic intervention, brought a wide range of reforms. These dealt with post-war issues, such as monetary problems, inflation, compensation for war victims, economic re-integration of Alsace and Moselle, and, last but not least, economic recovery and reconstruction in the “devastated territories”, including the “Charte des sinistrés” law (April 1919) and the establishment of the Crédit National bank (October 1919). But some laws also dealt with pre-war issues, like those aiming at improving the banking system (e.g. creation of the public Office national de Crédit Agricole in 1920) and the social laws on collective agreements (March 1919) and the eight-hour work day (April 1919). There were also long-term issues revealed by the war, such as the need for a national energy policy, which led to the creation of many semi-public companies during the 1920s.

Ultimately, the experiment of mixed economy during the Great War led to increasing, albeit reluctant, economic state intervention in the interwar period. The economic crisis of the 1930s amplified the war’s legacy, such as economic policies and planning. World War II made structural reforms possible.

Jean-Luc Mastin, Université Paris 8, IDHES (UMR 8533 CNRS)

Section Editor: Nicolas Beaupré

Notes

- ↑ Soutou, Georges-Henri: L’or et le sang. Les buts de guerre économiques de la Première Guerre mondiale, Paris 1989.

- ↑ Hardach, Gerd: La mobilisation industrielle en 1914-1918. Production, planification et idéologie, in: Cahiers du Mouvement social 2 (1977), p. 81-109.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Schneider et compagnie. Discours prononcé par M. Albert Thomas, sous-secrétaire d'Etat de l'artillerie et des munitions lors de sa visite aux Usines du Creusot, Le Creusot 1916, issued by PANDOR, online: https://pandor.u-bourgogne.fr/archives-en-ligne/ead.html?id=FRMSH021_00020&c=FRMSH021_00020_AFB-1-3-1-1-11-5 (retrieved: 2 August 2023).

- ↑ Druelle-Korn, Clotilde: De la visite des arsenaux au bilan de 1919, Etienne Clémentel et l’industrie pendant la Grande Guerre, in: Fridenson, Patrick / Griset, Pascal (eds.): L’industrie dans la Grande Guerre, Paris 2016, pp. 231-243.

- ↑ Projet de réorganisation des services du ministère du Commerce et de l’industrie, Paris 1917, p. 155; Rapport général sur l’industrie française, sa situation, son avenir, Paris 1919, p. 2392.

- ↑ Broadberry, Stephen / Harrison, Mark (eds.): The Economics of World War I, Cambridge 2005, p. 15.

- ↑ Bock, Fabienne: L'exubérance de l'État en France de 1914 à 1918, in: Vingtième Siècle, Revue d'histoire 3 (1984), pp. 41-52.

- ↑ Druelle-Korn, Clotilde: Clémentel, le ministre et ses ministères (1915-1919). Clémentel précurseur de l’Économie nationale, in: Kessler, Marie-Christine / Rousseau, Guy (eds.): Etienne Clémentel (1864-1936). Politique et action publique sous la Troisième République, Brussels 2018, pp. 189-204; Druelle-Korn, Clotilde: Clémentel précurseur de l’Économie nationale, in: Kessler, Marie-Christine / Rousseau, Guy (eds.): Etienne Clémentel (1864-1936). Politique et action publique sous la Troisième République, Brussels 2018, pp. 299-316.

- ↑ Godfrey, John F.: Capitalism at War. Industrial Policy and Bureaucracy in France, 1915-1918, Lemington Spa 1987, p. 257.

- ↑ 24 Octobre 1917. La chaussure nationale, issued by Archives départementales du Pas-de-Calais, online: https://www.archivespasdecalais.fr/Decouvrir/Chroniques-de-la-Grande-Guerre/A-l-ecoute-des-temoins/A-l-ecoute-des-temoins/1917/La-chaussure-nationale (retrieved: 2 August 2023).

- ↑ Godfrey, John: Capitalism at war. Industrial policy and bureaucracy in France, 1914-1918, Oxford 1987, p. 142 .

- ↑ Berneron-Couvenhes, Marie-Françoise: Les transports maritimes dans la guerre. Contraintes et adaptations, in: Fridenson, Patrick / Griset, Pascal (eds.): L’industrie dans la Grande Guerre, Paris 2016, p. 36-51.

- ↑ Langlinay, Erik: L’industrie chimique française en guerre (1914-1918). De la dépendance étrangère à l a construction d’une filière nationale, in: Entreprises et Histoire 85 (2016), pp. 54-69.

Selected Bibliography

- Bonin, Hubert: La France en guerre économique (1914-1919), Publications du Centre d'histoire économique internationale de l'Université de Genève, Geneva 2018: Droz.

- De la pensée à l'action économique : Étienne Clémentel (1864-1936), un ministre visionnaire, volume 16, 2012, 2012, pp. 40-54.

- Carls, Stephen Douglas: Louis Loucheur, 1872-1931. Ingénieur, homme d'Etat, modernisateur de la France, Histoire (Presses universitaires du Septentrion), Villeneuve d'Ascq 2000: Presses universitaires du Septentrion.

- Chancerel, Pierre: Le marché du charbon en France pendant la Première Guerre mondiale (1914-1921), thesis, Paris 2012: Université Paris Ouest.

- Descamps, Florence / Quennouëlle-Corre, Laure (eds.): La mobilisation financière pendant la Grande Guerre: le front financier, un troisième front, Paris 2015: Comité pour l'histoire économique et financière de la France.

- Fabien Cardoni (ed.): Les banques françaises et la Grande Guerre, Journée d'études du 20 janvier 2015, Paris 2016: Institut de la gestion publique et du développement économique.

- Fridenson, Patrick (ed.): 1914-1918, L'autre front, Cahiers du "Mouvement social", Paris 1977: Editions ouvrières.

- Godfrey, John F.: Capitalism at war. Industrial policy and bureaucracy in France, 1914-1918, Leamington Spa 1987: Berg.

- Joly, Hervé: Les dirigeants des grandes entreprises Françaises dans l’économie de guerre. Essai de synthèse, in: Guerres mondiales et conflits contemporains 267/3, 2017, pp. 5-16.

- Kuisel, Richard F.: Le capitalisme et l'état en France: modernisation et dirigisme au XXe siècle, Paris 1984: Gallimard.

- Le Bras, Stéphane / Dornel, Laurent (eds.): Les fronts intérieurs européens. L'arrière en guerre (1914-1920), Rennes 2018: Presses universitaires de Rennes.

- Machu Laure / Isabelle Moret-Lespinet / Vincent Viet (eds.): Mains-d’œuvre en guerre 1914-1918, Paris 2018: La documentation française.

- Marie-Christine Kessler / Guy Rousseau (eds.): Étienne Clémentel (1864-1936). Politique et action publique sous la Troisième République, Brussels 2018: Peter Lang.

- Mastin, Jean-Luc: Victimes et profiteurs de guerre? Les patrons du Nord, 1914-1923, Rennes 2019: Presses Universitaires de Rennes.

- Porte, Rémy: La mobilisation industrielle: "premier front" de la grande guerre?, Paris 2006: 14-18 Éditions.

- Rossignol, Jean-Luc / Touchelay, Béatrice: Bénéfices de guerre : La naissance du contrôle des bénéfices : l’impact de la contribution extraordinaire sur les bénéfices de guerre (1916-1957), in: Bensadon, Didier / Praquin, Nicolas / Touchelay, Béatrice (eds.): Dictionnaire historique de comptabilité des entreprises, Histoire et civilisations, Villeneuve d'Ascq 2018: Presses universitaires du Septentrion, pp. 237-239.