Introduction: A History of the Private Life of Couples during the War↑

Since the publication of the five volumes of A History of Private Life, edited by Philippe Ariès (1914-1984) and Georges Duby (1919-1996) in the late 1980s[1], there has been an increase in France in thought about and research into the everyday life of populations, as well as into their private lives and emotions. Alongside this, increased interest in the cultural history of the Great War has opened up new research topics focused among other things on the everyday life of soldiers, the history of families during the war and ties between the war- and home fronts.

Historians have analysed different sources to study how the First World War disrupted people’s private lives. Essays, novels, narrative accounts, iconographical documents, songs, press articles, as well as parliamentary debates and legal sources have all been used to examine the boundary between private life and the public sphere. Renewed interest in archives containing personal narratives, and the push to publish soldiers’ journals and correspondence between those at the front and those behind the lines, have made it possible to study how families and couples were reshaped by the war and how they expressed their affection and emotions.

The war brutally disrupted the private lives of French families since practically all families were affected by a departure for the frontlines. These disruptions are particularly patent when we look at couples’ relationships. This article will examine how conjugal ties are influenced by separation in war, approached here in the very specific context of the First World War which, by massively mobilizing men, also massively separated families. Indeed, at least 5 million couples were separated during the four years of the war. By mobilizing 7.9 million men – 80 percent of all men between the age of eighteen and forty-eight –, the separation of couples in France was both a personal and collective experience.

Examining the private lives of couples during the Great War involves analysing how the war changed the make-up of private and everyday life for couples; it also involves observing the shifting boundaries between private life and public affairs. This article will address the consequences of the war on the private lives of couples in three parts: we will first examine the government measures taken in favour of couples separated by the war; then we will discuss the economic and familial disruptions caused by their separation; and, lastly, we will analyse how long-distance intimacy was invented, primarily through letter-writing.

The Private Sphere at the Core of Public Affairs↑

French lawmakers were worried about what would happen to couples separated by the war. Numerous measures were taken to address this and aimed to palliate the scope of disruptions caused by the war. Indeed, legal measures were taken to adapt to the new conjugal reality created by separation. The marriage and divorce of mobilized men, the formality of wedding rituals, the remarriage of widows, posthumous marriage and its effects, protecting the inheritance of soldiers killed in the war, authorization for married women to go to court and exert paternal authority when their husbands were mobilized, the allowance for soldiers’ families and the military status of fathers of large families were all important topics that truly made couples a central war issue. The laws of 5 August 1914 and 4 April 1915 are particularly emblematic of the government’s involvement in private life.

An allowance for the families of mobilized men↑

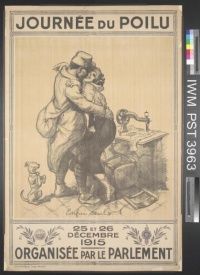

For the war to run smoothly, it appeared fundamental that families be able to maintain their economic situation. As soon as general mobilization was announced, the French government introduced a bill that aimed to provide an allowance for the families of soldiers for the duration of the war. It was adopted by the Chamber of Deputies in its most basic form and was presented to the Senate on 4 August 1914. The Senate declared an emergency, debated the bill immediately and proceeded to adopt it. Enacted on 5 August 1914, everyone was unanimous about the legislation: it was ratified by the Parliament “in the midst of eager applause” and was welcomed with “joy” and “enthusiasm[2]” in public opinion and newspapers. The daily allowance was 1.25 francs, with an additional 0.50 francs for each child under the age of sixteen. The allowance was increased in 1917 to address inflation and the context of moral crisis both in the army and on the home front: it was raised to 1.50 francs per day, with an additional 1 franc per child under the age of sixteen.

The government’s attempt to cover some of the needs of soldiers’ families and the creation of a war economy that was careful to supply the armies but also ensure the supply of essential goods and services on the home front played a non-negligible role in the outcome of the war. Economic hardship was indeed “limited in scope,”[3] particularly in the countryside, and France as such avoided a crisis like the one that struck the Central Powers.

Proxy marriage↑

The law passed on 4 April 1915 authorizing proxy marriage is another example of how marital affairs were taken into account in conducting the war. The law was exceptional and aimed to address an unusual conjugal situation; it was temporary since it applied only for the duration of the war; and it was voted as an emergency. And yet, the law on proxy marriage – despite its relative flop[4] – disconcerted, intrigued and bothered people since it challenged the eminent institution of marriage that was already perceived as weakened before the war. It gave married couples an important role to play in winning the war and attempted to save the marriage bond by recognizing the absence and suffering endured due to separation. At first glance – and if we believe its supporters – the law’s passing was driven by government compassion for hard-working soldiers who yearned to quickly marry the women they loved. And yet beyond this intimate aspect, the law sought to save the institution of marriage and in so doing the family institution and thus, more broadly, the endangered nation itself. When explaining their reasons and in discussions in the Chambers, the defenders of proxy marriage insisted on the twofold interest of the law which connected the patriotic and moral duties of men. Regulating couples was as such a broader means of participating in the politics of a country at war and of working for a victorious outcome. Legislating on marriage amounted to encouraging soldiers and protecting their morality and thus the morality of the entire country. The law even overshadowed the need for balanced public finances, since having to support a larger number of war widows was a potential burden on government coffers. The trendy rhetoric at the time – which involved the reaffirmation and regeneration[5] of families as the cornerstone of French society – sheds light on why, according to Jacques Catalogne (1856-1934), the law was “indisputably necessary”: “In voting this law, you will allow [soldiers] to unite their family duties and their military duties”.[6] The law as such served as a means of adapting to and accompanying the conjugal disruptions imposed by the war and of limiting their effects.

Disrupted family units↑

Economic instability↑

The departure of men for the war disrupted the basic family unit which, having lost an important member, was forced to adapt and make changes that greatly impacted everyday life. Without a doubt, the war was economically trying for many families. This was due to the compounded effects of unemployment and women entering the workplace, substantial losses of revenue which families depended on, increases in the cost of living, revenue losses for landlords affected by the moratorium on collecting overdue rent, the depletion of savings and the destruction of goods caused by the war. Many families were as such confronted with forms of impoverishment whose severity hinged largely on their economic status and activities before the war, their place of residence (e.g., rural or urban, proximity to the frontlines, occupied territory), family size and the strength of family-based solidarity.

Farm work had been completed in the summer of 1914 thanks to the creation of a network of solidarity; following this, however, the lack of manpower began to be felt in the French countryside in 1915. Luckily, the government allowance and higher agricultural prices worked to stave off the spread of poverty in rural France. Almost immediately and until the autumn of 1914, the situation was much worse in urban areas: the loss of income and the closing of numerous companies left some families on the brink of destitution. The moratorium on rent and the government allowance limited impoverishment, although what really stabilized the situation was the economic upturn in the autumn of 1914 and the return behind the lines of some of the workers initially mobilized. And yet price increases – which culminated in 1917 – worked to drain family savings and help explain the renewed sense of protest among members of the working class. Moreover, the war was particularly hard on small and medium-sized retailers, especially in small towns where the number of customers was greatly reduced[7].

The war as such made its way more or less brutally into the realm of home economics. The frequency with which letters between the war and home fronts dealt with economics indicates that it was a topic of prime importance for the population at war and a major source of concern among couples.

The reshaping of families↑

Mobilization changed the traditional family role held by each spouse and sources underscore the scope of reorganization that occurred in families during the war. Ascendants and extended family members sometimes became dependants, or, conversely, provided precious support to families. With their husbands away, wives became the central figure of the family economy and played a growing part; they sometimes received help from relatives, or conversely had to look after family elders. The war context and the departure for the front of a family member – often the main or sole breadwinner – meant that families had to redefine themselves.

The largest change was the shift of family responsibilities from husbands to wives. Despite the fact that the French civil code afforded women the same legal status as minors, once alone women nonetheless took on a prominent role running the household. Indeed, while women remained in charge of keeping house, the war also forced them to take over the farms and businesses left vacant by their mobilized husbands, manage the family’s affairs alone, do the banking, look after the children’s education and, occasionally, enter the workforce for the first time. This equivocal status undermined the traditional references for both women and men, the latter of whom were forced to observe such change from afar. Conjugal everyday life, which was already rattled by separation, was further upended by the central role assumed by women in managing the affairs of the home. Yet despite the fact that numerous women actively managed their husband’s affairs during the war, the decision-making clout of mobilized men did not disappear entirely when they left. “I am doing everything like I think I should, but I would like to have your opinion and hear whether you think my ideas are good[8]”, wrote Césarine Pachoux (1874-1956) in the first letter to her husband Joseph Pachoux (1874-1956), on 5 September 1914. From a distance and through their correspondence, men made suggestions and gave orders and instructions while their wives asked questions and sought advice and opinions. Women replaced their mobilized husbands, but they do not appear to have supplanted them entirely.

To counter impoverishment and the material shortages that came with their husbands’ departure – which the allowance granted by the law of 5 August 1914 did not always to cover –, some women also relied on new forms of family-based solidarity. This was the case mainly in rural areas where efforts were made to contain the worst economic effects at the scale of a family. Yet this shift in dependence sometimes worked in the opposite way, with soldiers’ wives occasionally becoming the backbone of family-based economic systems broken down by the war. Women were obviously required to meet the needs of their own children, but they sometimes also had to support their mobilized husbands at the front or while imprisoned, and even older family members incapable of providing for themselves. Indeed, in the family unit reshaped by the war, responsibility often extended far beyond meeting the needs of one’s own children.[9]

Reinventing intimacy↑

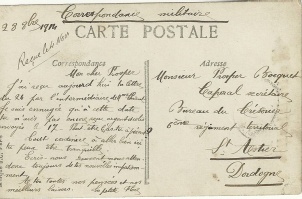

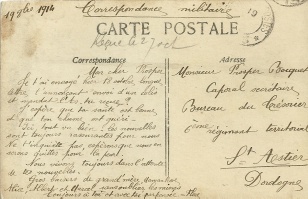

Couples separated by the war and forced to pursue long-distance relationships had very few opportunities to be alone during the war. Furlough and convalescence leave reunited spouses or fiancés occasionally, but these moments were often large family reunions. Given this, letters were one of the only means of being alone. Such privacy was relative, of course, since letters were often read to relatives and mail was quickly monitored by postal checks. For couples, letter-writing nonetheless offered an extension of their relationship interrupted by the war, substituted for everyday normality and helped fill a void. Many couples forged a veritable epistolary pact:[10] since conjugal conversation was possible only via this means, writing became a condition for the very existence of separated couples.

The epistolary ritual↑

Right from the start of the war, letter-writing played an important role in the lives of families separated by the war. In their first letters, soldiers explained where they had been, described the landscape covered and mentioned acquaintances encountered. Their wives gave news of family and friends, and updated them about the state of work left incomplete when they left for the war. In both cases, one party sought to reassure the other from afar. Mobilized soldiers attempted to prove that fear over their wellbeing was unfounded. Their wives talked about the economic and familial reorganization that was occurring, something which belief in a short war made possible to envisage as temporary. But the war’s duration over the long term turned conjugal correspondence into a system. The conditions and act of writing, the length and frequency of letters were gradually conceived and codified into a ritual that was vital for the relationship of couples at war.

Days were punctuated with the writing, waiting for and reading of letters; the number of days it took for a letter to reach its destination quickly came to symbolize the physical distance between people. The relationship of couples separated by the war refocused around letters, which became emotional objects par excellence: surprise or joy when they arrived – and deception or worry when they did not – were all emotions driven by the presence or lack of mail. “I am glowing... I received a letter from you. I no longer feel the same after reading your tender words. It seems like everything is better again and I have the will to live...”[11] wrote Yvonne Retour (1890-1971) in March 1915. A week later, she wrote, “It is dark and grey today, especially since I did not receive a letter from you.”[12]

Letters were the main marital connection during the war and as such became the “horizon of expectation”[13] of separated couples. The content of such expectation varied between the war and home fronts, however. For women, waiting intensified the sense that their husbands were in danger and left open a “terrible question mark.”[14] Naturally, worry arose as soon as a letter was late since news was indeed proof that a soldier was alive and well. For men at the front, the lack of mail from home was not loaded with the same tragic potential. And yet a prolonged delay in news nonetheless caused worry; soldiers commonly expressed concern for the wellbeing of their loved ones.

The somewhat restrictive side of the epistolary ritual should not be overlooked, however. The frequency with which letters were written, their format and content symbolized – or even represented – the strength of the bonds that united couples. The epistolary pact was as such implicitly based on three things: regularity, reciprocity and sincerity. When these expectations were not fulfilled, they could cause tension within a couple.

Long-distance love and sexuality↑

Given the distance imposed between soldiers and their wives, the war made it necessary for couples to express in writing their feelings of love and sexual desire. Letter-writing as such encouraged the expression of intimacy. Letters were a reserved, private place in which words could flow freely in an exchange. Letters were also a convenient medium, since while separation made people miss each other, the lack of direct contact helped them open up. By separating hundreds of thousands of couples, the First World War generated a phenomenal amount of epistolary talk in which spouses – in expressing their love – stoked and sparked feelings, emotions and desire.

The forms of address adopted – passionate or detached, conventional or original – serve as segues into each letter and its tone. They expressed tenderness, forged ties between the letter writers and renewed the commitment and love of each party. Written regularly, letters allowed the marital pact of both long-standing and relatively new couples to be constantly renewed. Their attachment was also expressed when talking about the suffering caused by separation. Indeed, the war subjected people’s love to the experience of absence. It allowed people to miss each other and therefore also to express such feelings.

The First World War is a particularly fertile, albeit ambiguous period for studying sexual practices. Indeed, for four years, the separation of couples made it virtually impossible to satisfy their marital desires. And yet paradoxically, this constraint pushed them to write massively on topics surrounding or about sexuality. Expressing their sexual desire in writing was an absolute novelty for a great majority of letter writers. “It is not easy to talk about love to a husband you’re crazy about because there are things we do, that we do not talk about, and those are indeed the best things,”[15] wrote Marie-Josèphe Boussac (1886-1929) in July 1915. The writing that separated couples had to resort to as such gave rise to a new practice: the expression of desire. In this respect, letter-writing even occasionally became a substitute sexual activity.

A Ubiquitous Idea: Reuniting, Leave and the End of the War↑

As early as August 1914, letters were filled with imagining the return of men from the front. From the start of the war to the first large-scale losses, and even more so as the war drew on, the most constant and widespread project commonly imagined by couples was putting an end to their separation. “There is a war on, but the main thing for us in all this is coming home”[16] wrote Hippolyte Bougaud (1884-1931) in November 1915. Letters were de facto filled with a dual expectation: that of temporarily reuniting – within the army zone or while on leave, for example –; and the more powerful but also more hypothetical idea of the soldier’s definitive return home.

During the first months of the war, belief in a short war made it easy to talk about soldiers’ safe and healthy return. The reunions imagined were possible with a quick and certain victory. Jean-Jacques Becker has shown that this hope began to fade starting after the first month of war[17]. Although the outlook was less and less optimistic in the following months, people continued to nonetheless envisage the end of the war and the permanent return of men. The granting of leave starting in July 1915 – which aimed to help morale at the front and behind the lines – and the idea of authorized reunions changed the stakes. More than the vague, far-off end of the war, soldiers and their loved ones focused on the idea of a temporary return.

The first wave of soldiers on leave marked a turning point in people’s correspondence: spouses devoted an important share of their writing to the idea of a future reunion or to memories of days spent together. As soon as leave was implemented, it became a key moment – real or imagined – that punctuated the time couples spent apart. Leave allowed couples to find balance between two moments: the carefully counted time since their last separation and the estimated but uncertain time left before their next reunion. Many departures were indeed delayed or cancelled, since leave also depended on unpredictable military operations. After the first disappointments, uncertainty trumped. Although all announced leave was a reason for couples to celebrate, caution was needed. Leave was a source of frustration, too, since it was uncertain and too short; it was also bound up with the idea of another inevitable separation to follow, which got harder with each departure since the prospect of death was very real and uncertainly abounded over the next reunion. That is why obsession over leave was gradually accompanied and even replaced by imagining once again the end of the war. The idea of a definitive return came to counter that of a temporary reunion, which was merely a parenthesis in the war.

Many couples imagined the soldier’s return and the return to family life after the war. Each couple – and even each spouse therein – obviously created their own imaginary return, based on their own unique marital history. It is nonetheless remarkable to note the precision with which couples constructed veritable scenarios and precisely planned out the actions, feelings and backdrops of their reunions. Letter-writers imagined the after-war, the soldiers’ return and their future together with remarkable constancy. That is how they filled the long wait – and undoubtedly made it endurable. Yet such obstinacy to always talk with certainty about their return also points up the depth of people’s anguish. The obsession with going home was also an obsession to survive, a means of refusing the possibility of death – and also, therefore, a sign of its striking presence.

Conclusion: The Silence just after the War↑

The war, which has been described as an “emotional catastrophe,”[18] rocked marital histories and occasionally destroyed intimate relationships. But what happened just after the war? The men’s return put an end to the epistolary ritual. Historians interested in understanding how intimacy was reintegrated into the everyday lives of married couples after the war have to contend with the abrupt end of personal narrative sources that came with the end of the First World War. This lack of sources is surely a sign of the ambient silence after the war as marital life worked to realign with the normality of everyday life.

Clémentine Vidal-Naquet, Paris-Sorbonne

Section Editor: Nicolas Beaupré

Translator: Jocelyne Serveau

Notes

- ↑ Ariès, Philippe and Duby Georges (eds.): A History of Private Life. 5 volumes, Cambridge 1992-1998.

- ↑ Fonvielle, André: Etude critique du régime des allocations aux familles des militaires soutiens indispensables. Fondement juridique de cette législation, son fonctionnement pratique, ses répercussions, Montpellier 1919, pp. 24-25, translated by JS.

- ↑ Becker, Jean-Jacques and Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane: La France, la nation, la guerre, Paris 1995, p. 324.

- ↑ Between April 1915 and April 1921, less than 0.5 percent of weddings were marriages by proxy.

- ↑ Le Naour, Jean-Yves: Misères et tourments de la chair pendant la Première Guerre mondiale. Les mœurs sexuelles des Français, 1914-1918, Paris 2002.

- ↑ Catalogne, Jacques: Minutes of the 14th session of the Senate on 18 March 1915, Journal Officiel, 19 March 1915, translated by JS.

- ↑ Becker, Jean-Jacques: La France en guerre. 1914-1918. La grande mutation, Paris 1988, pp. 87-108.

- ↑ Sarda-Cochet, Honoré: War correspondence (1914-1918) between Césarine and Joseph Pachoux from Mézériat (Ain), typescript, Ambérieu-en-Bugey, Association pour l’autobiographie, serial mark 1407, p. 2, translated by JS.

- ↑ Given that age tends to accentuate economic vulnerability, ascendants were much more likely to benefit from such family-based solidarity.

- ↑ Dauphin, Cécile/Lebrun-Pezeat, Pierrette/Poublan, Danièle: Ces bonnes lettres. Une correspondance familiale au XIXe siècle, Paris 1995, p. 99, p. 131.

- ↑ Retour, Maurice and Yvonne (Patrice Retour, ed.): Les nouvelles fiançailles. Correspondance de guerre, 1914-1915, Nantes 2001, p. 272, translated by JS.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 290, translated by JS.

- ↑ Koselleck, Reinhart: “Champ d’expérience” et “horizon d’attente” : deux catégories historiques, in: Le futur passé. Contribution à la sémantique des temps historiques, Paris 1990, pp. 307-329.

- ↑ Portes, Jules: Souvenirs et correspondance de guerre, Paris 1915, letter from 8 September 1914, p. 8; translated here.

- ↑ Boussac, Jacques: Correspondance de Jacques et Marie-Josèphe Boussac. 1914-1918, Paris 1996, Jouve, published by the family, p. 141.

- ↑ Mougeot, Félicie and Bougaud, Hippolyte: Correspondance 1914-1919, http://bougaud.free.fr/hippo/Guerre1418/corhipfel.pdf (Retrieved 4 May 2015), p. 33.

- ↑ Becker, Jean-Jacques: 1914. Comment les Français sont entrés dans la guerre, Paris 1977, p. 571.

- ↑ H.F.C.: L’arrière tragique, in: La Grande Revue, Paris, #90, July-October 1916, p. 480, translated by JS.

Selected Bibliography

- Cabanes, Bruno / Piketty, Guillaume (eds.): Retour à l'intime au sortir de la guerre, Paris 2009: Tallandier.

- Capdevila, Luc / Rouquet, François / Virgili, Fabrice et al.: Sexes, genre et guerres (France, 1914-1945), Paris 2010: Payot.

- Cronier, Emmanuelle: Permissionnaires dans la Grande Guerre, Paris 2013: Belin.

- Downs, Laura Lee: L'inégalité à la chaîne. La division sexuée du travail dans l'industrie métallurgique en France et en Angleterre, 1914-1939, Paris 2001: A. Michel.

- Duby, Georges / Perrot, Michelle / Thébaud, Françoise: Histoire des femmes en Occident, le XXe siècle, volume 5, Paris 1992: Plon.

- Fouchard, Dominique: Le poids de la guerre. Les poilus et leur famille après 1918, Rennes 2013: Presses universitaires de Rennes.

- Fridenson, Patrick: 1914-1918. L'autre front, Paris 1977: Editions Ouvrières.

- Grayzel, Susan R.: Women's identities at war. Gender, motherhood, and politics in Britain and France during the First World War, Chapel Hill 1999: University of North Carolina Press.

- Hanna, Martha: A republic of letters. The epistolary tradition in France during World War I, in: The American Historical Review 108/5, December 2003, pp. 1338-1361.

- Hanna, Martha: Your death would be mine. Paul and Marie Pireaud in the Great War, Cambridge; London 2008: Harvard University Press.

- Huss, Marie-Monique: Histoires de famille. Cartes postales et culture de guerre, Paris 2000: Noésis.

- Le Naour, Jean-Yves: Misères et tourments de la chair durant la Grande Guerre. Les mœurs sexuelles des Français, 1914-1918, Paris 2002: Aubier.

- Morin-Rotureau, Évelyne: Françaises en guerre, 1914-1918, Paris 2013: Autrement.

- Prochasson, Christophe: Aimer et gouverner à distance. Le témoignage des correspondances: 1914-1918. Retours d'expériences, Paris 2008: Éditions Tallandier, pp. 209-239.

- Prost, Antoine: Le bouleversement des société, in: Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane / Becker, Jean-Jacques (eds.): Encyclopédie de la Grande Guerre, 1914-1918. Histoire et culture, Paris 2004: Bayard, pp. 1177-1188.

- Roberts, Mary Louise: Civilization without sexes. Reconstructing gender in postwar France, 1917-1927, Chicago 1994: University of Chicago Press.

- Rollet, Catherine: The home and family life, in: Winter, Jay / Robert, Jean-Louis (eds.): Capital cities at war. Paris, London, Berlin 1914-1919, volume 2, Cambridge; New York 2007: Cambridge University Press, pp. 315-353.

- Rouquet, François / Virgili, Fabrice / Voldman, Danièle (eds.): Amours, guerres et sexualité, 1914-1945, Paris; Nanterre 2007: Gallimard; Musée de l'armée; BDIC.

- Thébaud, Françoise: La femme au temps de la guerre de 14, Paris 1986: Stock; L. Pernoud.

- Vidal-Naquet, Clémentine: Correspondances conjugales 1914-1918 dans l'intimité de la Grande guerre, Paris 2014: R. Laffont.

- Vidal-Naquet, Clémentine: Couples dans la Grande Guerre. Le tragique et l'ordinaire du lien conjugal, Paris 2014: Belles Lettres.