Introduction↑

The interwar period saw the emergence of a complex discourse about the First World War in the contemporary media. It reflected a number of intersecting themes, namely the attempts to establish official interpretations, the need for commemoration and mourning and the utilisation of the war for political purposes. This was shaped by the emergence of new mass media, such as radio and cinema. At the same time, established media, such as newspapers, books and pamphlets also discussed the war and its impact extensively during the interwar period. This discourse in the contemporary media highlighted the tensions between more traditional representations of the war, focusing on military and political aspects, and modernist views that often sought to capture the experiences of violence, loss and grief. In his classical study Fallen Soldiers, the cultural historian George L. Mosse (1918-1999) argued that the post-war media discourse was shaped by a “brutalisation” that facilitated the epidemic of political violence in interwar Europe.[1] This interpretation has been put into perspective more recently by historians, such as Jon Lawrence and Antoine Prost, who pointed out that, at least in Britain and France, the public war discourse facilitated a turn towards pacifism after 1918.[2] In fact, pacifist literature and films played an important – albeit controversial – role in the discourse about the Great War during the interwar years.

Old and New Media in the Interwar Period↑

The last decades of the 19th century and the years leading up to the First World War witnessed the emergence of modern mass media, particularly the rise of mass-circulation newspapers and magazines. This was facilitated by technological advances, such as the introduction of offset printing machines, which made it possible to print publications in larger quantities and to sell them at lower prices to an emerging mass readership. The new printing technologies also made it easier to include photos and coloured illustrations, which significantly changed editorial practices and the way events were reported. At the same time, the number of publications increased significantly – a trend that shaped the media landscape well into the interwar period. Between 1920 and 1939, the circulation of British newspapers increased by five percent, reaching approximately twenty million copies daily in 1939. Similarly, in France, daily newspaper circulation reached eleven million during the same period.[3] This trend could also be observed in other European countries and North America.

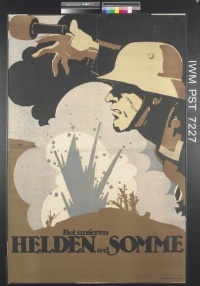

During the First World War, all belligerents used mass media and the new possibilities of mass communication for their propaganda efforts. Newspaper proprietors, editors and journalists were – in many cases voluntarily – integrated into the state propaganda apparatuses. Governments and military authorities were also instrumental in facilitating the use of new media for propaganda purposes. Particularly during the second half of the war, film was extensively used to reach mass audiences. In August 1916, the quasi-documentary The Battle of the Somme was released by the British government and was viewed by several million people within a matter of weeks. Although most of the combat scenes were staged behind the actual frontline, the film created a sense of immediacy for viewers on the British home front. Despite the graphic depictions of killed and wounded soldiers, the film is generally thought to have had a positive effect on the mobilisation of civilians for the war effort.[4] In January 1917, the German Supreme Command initiated the creation of the Picture and Film Office (Bild- und Filmamt) to produce war films. Later, in December 1917, the Universum Film AG (UFA) emerged from the office as the main film production company in Germany during the Weimar Republic. Throughout the war, film production companies, such as Gaumont or French Pathé and its various subsidiaries in Britain and the United States, produced newsreels that were shown in cinemas. This had a significant impact on the public perception of the frontlines, yet it also changed the aesthetics and visual language used to depict the war in the media in the 1920s and 1930s.

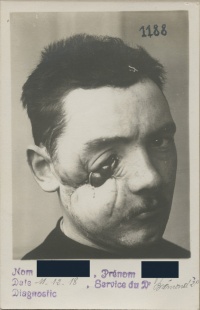

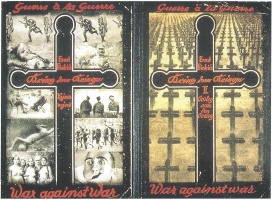

Photography was another important medium that shaped the visual representation of the war. Besides the official and propagandistic uses of war photos, the First World War and its impacts were also documented by millions of individuals who used comparatively cheap, mass-produced cameras to take snapshots of their own wartime experiences. In some cases, these photos were published in the interwar years alongside memoirs or war diaries. Film and photography, and their new possibilities of visual representation, had a profound impact on the war discourse in the media. Yet, the sense of authenticity and immediacy of these new media also had a subversive potential to challenge established imagery of the war. Graphic photos of disabled and facially disfigured veterans featured prominently in pacifist publications that significantly influenced the war discourse. In France, for instance, images of the “Gueles Cassées” (broken faces) became emblematic for the scarred war generation. In a similar vein, the German pacifist Ernst Friedrich (1894-1967) published his book Krieg dem Kriege(War against War) in 1924, which featured graphic photos of killed soldiers and mutilated veterans in order expose the brutality of the war.[5]

The latest medium to emerge after the First World War was the radio. Wireless technology made important advances during the war, and the first public and commercial radio stations were established in Europe in the early 1920s. In France, the first Paris-based station started broadcasting in 1921. The BBC was founded as a private radio company in October 1922. In Germany, the first private radio stations were set up in 1923. Italy and Austria followed these developments in 1924 with the establishment of their own national broadcasters. Like film and photography, the radio combined a sense of immediacy on the side of the listener with collective practices of media consumption, for example in public radio halls and later also in private homes. This became particularly visible on the occasion of anniversaries and remembrance days, such as the annual Armistice Day events in Britain and France on 11 November.

The possibilities of these new media shaped the discourse about the First World War profoundly. Photography, film and radio extended the range of what could be said and represented. It also reduced the perceived distance between those who experienced the war as combatants on the front and those who stayed at home.

War Guilt, Memoirs and Official Histories↑

Immediately after the war, debates about the responsibility for the war and the “war guilt question” became a key theme of the media discourse. This was a particularly sensitive issue, since it also implied responsibility for its casualties and the devastations the war had caused. Already early on, almost all belligerents used the international press to purport their own – often exculpating – versions of the outbreak of the war. By 1916, the view that the Great War was the result of aggressive German expansionism was commonplace in the international press. This was, however, challenged when, in November 1918, the People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs of the new Bolshevik government in Russia, Leon Trotsky (1879-1940), ordered the publication of secret treaties between the then Tsarist regime, Britain, France and Italy. They revealed that the Allied Powers also pursued imperial aims, such as the Russian ambition to seize Constantinople and control of the Bosphorus Straits. The German press sought to exploit the publication for its own propaganda while in the allied countries, the left-wing and pacifist groups published the secret treaties to push their own government towards a peace “without annexations and indemnities”. The British and French governments reacted by expanding censorship measures to avoid a negative impact on support for the war effort. Nonetheless, the publication of the secret treaties by the Bolsheviks had a lasting impact on the public discourse about the war in the interwar period. It fed into a widespread pacifist mood at the time that was reflected in numerous publications and films.

The “war guilt question” was again fuelled by the Treaty of Versailles in 1919. Article 231 determined the sole responsibility of Germany and her allies for the outbreak of the war. Although this was primarily intended to justify the significant reparation payments, most Germans also perceived this as a damning moral judgement. Despite the shared rejection of the Versailles Treaty from left- and right-wing groups in Germany, the discourse about the war itself was more nuanced. A case in point is the intense debates about the so-called “Bavarian Documents on the Outbreak of the War”. In November 1918, following the example of the Russian Bolsheviks, the revolutionary Bavarian government under Prime Minister Kurt Eisner (1867-1919) published hitherto secret documents about the expansionistic German war aims at the beginning of the war. These documents became a focal point within the German debate about the “war guilt clause” of the Treaty of Versailles since it undermined the dominant official views.[6] After the downfall of the short-lived socialist Bavarian republic in early 1919, conservative governments and right-wing groups sought to discredit the published documents as falsifications. While liberal and left-leaning newspapers sought to present a more nuanced view of the war and its causes, the conservative and right-wing press saw such publications as an all-out attack on German honour and national interest. The treatment of this case in the German media highlights the divided nature of German politics in the 1920s.

Officially, successive German governments rejected the notion of sole responsibility and went to great lengths to publicise their own interpretation of the outbreak of the war. Early on, it was recognised that international public opinion would have to play a crucial role in any attempt to revise the Treaty of Versailles. For this purpose, the Zentralstelle für die Erforschung der Kriegsursachen (Central Office for Research into the Causes of the War) was established as a private institute by the Foreign Office in Berlin. The explicit aim of the Central Office was to shape the international discourse on the war guilt question by publishing and funding research on the issue, organising conferences, and by placing articles and essays in international publications. It also published its own journal entitled Die Kriegsschuldfrage: Berliner Monatshefte, which levelled heavy criticism against article 231. In addition, journalists and renowned academics were integrated into these efforts by sponsoring the publication of books and newspaper articles. Politicians in France and Britain, such as Georges Clemenceau (1841-1929), openly attacked these attempts to revise the interpretation of the Great War. There was, however, some success in countries such as the United States, where the provisions of the Versailles Treaty were increasingly seen as insufficient and in need of revision by the mid-1920s.

Controversies about responsibility for the war were not confined to Germany. In Britain, there were intense public debates about the causes of the war. One of the most relevant examples is Arthur Ponsonby’s (1871-1946) 1928 book, Falsehood in Wartime.[7] According to Ponsonby, the British public was deliberately lied to in 1914, and consequently manipulated into supporting a disastrous war. By analysing examples of so-called “atrocity propaganda” during the war, Ponsonby sought to expose a collusion between the press and the British state. The book itself caused controversy about the role of the media in democratic societies. While it was widely acknowledged that Ponsonby had exposed some blatant propaganda lies, newspapers such as The Times also pointed to cases where evidence for actual German war crimes had been omitted. Nonetheless, Falsehood in Wartime left a lasting mark on debates over the outbreak of the First World War until today.

There were also more comprehensive attempts to establish dominant interpretations and narratives of the war in the public. Official war histories became an important aspect of the post-war discourse since they represented the state-sponsored version of events. Often written in deliberately non-emotive prose, these publications asserted an authoritative interpretation of the war. Most of these official war histories were published by national archives or the historical divisions of general staffs. In Britain, the Committee of Imperial Defence commissioned the writing of the so-called History of the Great War Based on Official Documents, which was published in multiple volumes from 1923 onwards.[8] The French general staff ordered its Historical Service to produce a definitive history of the Great War in 1919. Between 1922 and 1937, several multi-volume accounts of the different stages of the war were published by the Imprimerie Nationale in Paris. The German Reichsarchiv began publishing its official history of the war in 1925. In addition to the official war histories, there were publications aiming at a more general audience. During the war, The Times had issued weekly supplements with articles, maps and photographs on the course of the war. After 1918, a twenty-two-volume encyclopaedia of the war was published by The Times, making it one of the most widely read histories of the war in English. In contrast to the official war histories, its focus was not merely on military and political developments, but included discussions of issues such as the situation on the home fronts, propaganda and the economy of the war. The most ambitious attempt to engage with the social and economic impacts of the war was multi-volume Social and Economic History of the World War by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. The series consisted of national series that covered very diverse developments in major belligerents. By 1924, more than 200 individual studies by historians, sociologists, economists and political scientists had been published. The aim of the Carnegie Endowment was to provide a scholarly interpretation of the war that differed from the official government histories, and their implicit and explicit political aims. Yet, the Carnegie History was also intended to overcome the nationalistic narratives of the war, and to offer a more nuanced interpretation. It also contributed to the re-establishment of transnational intellectual networks that had existed before the war.[9]

The official attempts to shape the contemporary discourse about the war were supplemented by the publication of memoirs by politicians and military leaders, which often appeared in serialised versions in newspapers and magazines. For example, the German supreme commander Paul von Hindenburg (1847-1934) published his memoirs Aus meinem Leben (Out of My Life) in early 1920, with an English translation being released almost simultaneously.[10] His companion Erich Ludendorff (1865-1937) had published his own book entitled My War Memories in 1919.[11] Both books were designed to deflect any responsibility for the German defeat and advanced their own version of the “stab in the back myth”. At the same time, they were received with great interest by the international press and parts appeared serialised in relevant newspapers. Similarly, British and French generals published their own war memoirs. The British Field Marshal Douglas Haig (1861-1928) published a redacted collection of his wartime dispatches in book form in 1919.[12] The tenth anniversary of the end of the war in 1928 triggered another wave of war memoirs. Against the backdrop of the political developments of the 1920s and the increasingly critical view of the war, many of these publications were yet again designed to deflect blame for the disastrous impact of the war. A relevant case in point are the War Memoirs of the former British prime minister, David Lloyd George (1863-1945), published from 1933 onwards.[13] Lloyd George sought to shift the responsibility for the large number of casualties away from political decision makers by blaming the poor decisions of military leaders, such as Field Marshal Haig. The image conveyed in these war memoirs was that of an often incompetent military leadership, unable to learn from past mistakes, but nevertheless willing to sacrifice the lives of ordinary soldiers. This view had a lasting impact on the public discourse of the war in Britain, where the phrase “lions led by donkeys” became a commonplace in the public debates about the war. In the early 1930s, numerous similar war memoirs were published, such as those of the allied supreme commander on the Western Front, Marshal Ferdinand Foch (1851-1929). The fact that most of these memoirs were published almost simultaneously in their national languages and in English highlights the inter- and transnational nature of the war discourse in the interwar years.

These official accounts were, however, contrasted by the publication of the – sometimes fictionalised – memoirs of frontline soldiers that presented a different perspective on the realities of the war. The first widely read accounts that reflected the “frontline experience” had already been published during the war itself. These hybrid war memoir/novels were in most cases written by young, comparatively well-educated infantry officers. The voices of working-class soldiers, often idealised as “Tommies”, “Poilus” or “Landser” in the wartime propaganda, were in comparison quite rare in the war discourse of the 1920s and 1930s. The most prominent example of these (fictionalised) war memoirs, Henri Barbusse’s (1873-1935) novel Le Feu (Under Fire), came out in 1916.[14] Although fictional, many contemporaries saw it as an authentic account of the reality on the frontline. Barbusse used his literary fame and his reputation as a soldier to play an active role in left-wing veteran organisations and as a communist activist in interwar France. In Germany, the former infantry officer Ernst Jünger (1895-1998) published the first edition of his war memoirs In Stahlgewittern (Storms of Steel) in 1920.[15] Throughout the interwar period and after the Second World War, several changed editions were published. Just like Barbusse in France, Jünger came to be seen as an authentic voice of the ordinary soldier in the trenches, which added relevance to their books in the contemporary perception and discourse about the war. In the wake of the memory boom after 1928, more war memoirs were published. Among them were important books, such as Edmund Blunden’s (1896-1974) Undertones of War in 1928, which went through seven impressions in just one year, or Siegfried Sassoon’s (1886-1967) Memoirs of an Infantry Officer in 1930. The attributed realism of these memoirs with their often very graphic depictions of violence, killing and dying in the trenches, shaped the public image of the war and contributed to widespread pacifist attitudes.

Veterans, Commemoration and Mourning in the Media↑

The need to commemorate and mourn the war dead was another key element of the post-war discourse. The sheer scale of the loss of human life was unprecedented for most contemporaries. Some eleven million combatants were killed, and between six and seven million civilians perished because of the war. The experience of loss was so widespread that it necessitated the creation of new forms of commemorative practices that integrated the local, regional and national stages. Media played a crucial role in this process. Indeed, they shaped the invention of new commemorative rituals and traditions. Particularly on the occasion of the Armistice Day or the Volkstrauertag (People’s Day of Mourning) in Germany and Austria, the new possibilities of radio and film were used to full effect. These memorial days themselves became media events during the interwar period. Broadcasting central commemorative events from the capital cities across the country and empires helped to foster a sense of national belonging, yet it also allowed for local and individual practices to be embedded into collective rituals.

In Britain, Armistice Day had first been observed on 11 November 1919 with a nationwide two-minute silence.[16] Locally, individual events were organised by veterans and families of fallen soldiers. There was very little that connected these events apart from the desire to commemorate the end of the war. Depending on local circumstances, Armistice Day events in 1919 could even turn into radical political protests. From 1920 onwards, more organised forms of commemoration emerged and the media, particularly the radio, played a crucial role in the invention of traditions. In 1920, the commemorations were for the first time held at the newly erected Cenotaph in Whitehall. This was filmed and shown in newsreel cinemas around the country. The media coverage of the event facilitated a process of standardising the commemorations across Britain. By 1921, the newly-founded, state-sponsored British Legion took over the organisation of most commemorative events in the country. The underlying idea of the two-minute silence at 11 am was to combine individual, local remembrance with collective acts of commemoration held simultaneously across the country. In 1923, the BBC began to broadcast a special programme on Armistice Day. The beginning of the nationwide two-minute silence was signalled by the bugle signal “Last Post” and its end by the “Reveille”. This was followed by a sermon broadcast from the London studio. Throughout the 1920s, the Armistice Day programme was gradually extended to include speeches by politicians and military leaders, concerts and literary readings. During the 1920s, the reach of the radio had increased significantly. By 1927, there were over 2.7 million radio licences in Britain, a number that would more than triple by 1939. From 1937, the BBC began to broadcast live from the Cenotaph in London, allowing people all over the country, and indeed the Empire, to participate in the ceremonies.

The radio broadcasts of the BBC on Armistice Day not only shaped how the war was commemorated, but increasingly also influenced what was remembered. A relevant case in point is the so-called “Festival of Remembrance”, which was organised on the evening of Armistice Day by the British Legion, from 1923. The BBC began to broadcast the event live from the Royal Albert Hall in 1927. The choice of the music selected for the festival represented a significant shift in the popular perception of the war. In the first years of the festival, very sombre classical music pieces were played. However, when the BBC began to broadcast the event live, producers selected tunes that were seen as more appealing to the general radio audiences. Now, famous wartime songs, such as “Tipperary”, sung by popular artists, were included in the programme alongside the established bugle signals and the two-minute silence. The Armistice Day broadcasts combined the celebration of victory with collective remembrance and a certain sense of war nostalgia. Yet, they also incorporated entertainment as part of the programme. This highlights the ambiguous character of the war discourse in Britain.

In Germany, the so-called Volkstrauertag, or People’s Mourning Day, developed along similar lines, yet with some striking differences. In 1919, the Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge (German War Graves Commission or VDK) proposed a national day of mourning and recollection for the war dead. The aim was to bring together all Germans on this occasion of national remembrance, transcending party politics, class and religion. The first commemorative events were held in the Reichstag in 1923 as part of the Volkstrauertag. By 1925, it was recognised as the official memorial day for the First World War, though not made an official national holiday. From the beginning, radio played a crucial role in the attempts to create a unifying narrative of war commemoration. The first memorial event in 1923 had only been broadcast regionally by the Berlin station and media coverage was generally patchy. However, by 1925, the Volkstrauertag had become a national media event similar to Armistice Day in Britain. The Berlin station would broadcast live from the Reichstag with other regional stations, except for Bavaria and Stuttgart, picking up the programme. As well as the live broadcast from the Reichstag, speeches, readings and poems were included in the programme. Generally, the broadcasts were marked by a sombre mood and repeated references to Christian iconography.[17] The theme of collective mourning clearly dominated the official Volkstrauertag events. Contemporaries recognised that the live broadcasts were an essential element as they allowed the direct participations of those at home or listening in radio halls, thus creating a moment of national unity.

Yet, the attempts to establish the Volkstrauertag as a national day of mourning were contested throughout the existence of the Weimar Republic. The far left, led by the Communist Party (KPD), rejected it as the “day of the war-mongers” for the failure of the government to condemn the war. The far right, on the other hand, refused to participate in the official commemorations because it perceived the focus on collective mourning as a tacit acknowledgement of defeat and the futility of the war. Far-right and conservative nationalists, such as the NSDAP or the Stahlhelm, tried to establish alternative days of commemoration, particularly the so-called “Langemarck Day” each November. This was used as an occasion to promote the ideals of martial valour and to commemorate the “selfless sacrifice of the German youth” at the Battle of Langemarck in November 1914. Later in the 1930s, the National Socialist regime renamed the Volkstrauertag to the “Heldengedenktag” (Heroes’ Memorial Day) in order emphasise the “selfless sacrifice of the German youth” in November 1914.[18] The debates in the German press reflected the tensions between these conflicting interpretations of the war and their political implications. Depending on their political alignments, newspapers and other media outlets were instrumental in promoting these views to the wider public. Different Weimar governments made some effort to influence public opinion through the creation of collective rituals, such as the Volkstrauertag, yet failed to establish a coherent, integrative narrative. Instead the public sphere was fragmented along political lines. The far right sought to uphold notions of military heroism and the meaningful self-sacrifice of the fallen soldiers. The left, on the other hand, remembered the fallen primarily as futile victims of an imperialistic war. The official commemoration with emphasis on Christian symbolism and mourning failed to satisfy either side. Rather than creating a unifying narrative, the politically aligned press often aggravated these conflicts.

A key figure dominating the post-war media discourse was that of the veteran. This became particularly visible in France, where veterans’ organisations played an important political role during the interwar period. The first veterans’ groups were already established during the war, and by 1920 two main organisations had emerged, the left-wing Association Républicaine des Anciens Combattants (ARAC) and the state-sponsored Union Nationale des Combattants (UNC). Both were set up to campaign for better pensions and social welfare for ex-servicemen in France, yet from the mid-1920s they also represented different interpretations of and attitudes towards the war. The ARAC became aligned with the French Communist Party (PCF), while the UNC shifted gradually to right of the political spectrum. This was also reflected in the journals and publications of both organisations. From 1919, the ARAC published numerous national and local weeklies, such as L’Ancien Combattant and L’Antiguerrier, which transported the pacifist political messages of the French left to the veterans. This was in large part the result of the involvement of prominent activists and writers, such as Henri Barbusse, who became important cultural and political figures in this period. During the so-called Popular Front from 1936 to 1938, the ARAC and its media outlets became vocal supporters of the left-wing government. At the beginning of the 1930s, the UNC became increasingly involved in partisan politics as well. Its weekly paper La Voix des Combattants reflected this shift, as it increasingly became a platform for far-right views. Under its president Georges Lebecq (1883-1956), the UNC mobilised its members for the riots of 6 February 1934 in Paris and consequently established close links to anti-republican and fascist groups. Both sides of the political divide used the image of the “ancien combatant” for their own purposes. Because of their perceived authenticity, views of veterans, as expressed in their publications, played a key role in the public discourse about the war in France. The media representation of the veteran differed significantly, depending on purpose and political intentions – ranging from depicting them as heroic defenders of the country to victims of a futile war.

Yet, despite the political divisions, there were also attempts to unify the ex-servicemen community and their families. Radio played a crucial role in these endeavours. By the end of the 1920s, there were several charities that provided free radio sets to blind or infirm veterans. This was not merely designed to facilitate rehabilitation, but was seen as an attempt to reintegrate mutilated ex-servicemen into the public life of the republic. Listening to radio programmes allowed blind veterans to participate in the political process, something historian Rebecca F. Scales has described as “radio citizenship”.[19] The fact, however, that by the late 1920s the French state had more or less established a monopoly over radio broadcasting also allowed to use the radio as a national, state-sponsored medium to shape and influence the popular representations of war.

Brutalisation and Pacifism in the Interwar Media↑

One of the most debated features of the media discourse is the alleged brutalisation of European societies after the war. In particular the historian George L. Mosse saw the media and its use of violent language and imagery during the interwar years as the main reason for the flaring political violence of the period. In his seminal work Fallen Soldiers, he argued that the public discourse was marked by a dehumanisation of political opponents and a devaluation of human life. For Mosse, this was a direct result of the experience of extreme violence during the war and a continuation of the violent wartime propaganda. The main evidence for this development was taken from various publications of the time, ranging from magazines and newspapers to children’s literature and films. The emphasis on the role of mass media is important in this context as it extended the brutalising effects of the war to those who did not experience extreme violence first hand. Mosse cites various examples for the use of dehumanising language in the political discourse of the 1920s, for example the equating of political opponents to vermin or their degradation to “subhumans”. At the same time, extreme violence was glorified and celebrated in the media discourse, leading to a general devaluation of human life and general desensitisation towards violence. While most of Mosse’s observations are valid, his brutalisation thesis has been put into perspective by newer research. Antoine Prost argues, for instance, that French soldiers were able to frame their wartime experiences differently, drawing on the republican and humanist traditions of the republic. Similarly, Jon Lawrence points out that concerns over the brutalisation of ex-servicemen and the political conflicts of the immediate post-war period led to a reinvention of Britain as a “peaceable kingdom”. Nonetheless, clear signs of what Mosse described as “brutalisation” could certainly be found in all European societies, particularly in the fascist regimes of the interwar period as well as in the Soviet Union.

The focus on the question of political violence and brutalisation does, however, only represent one aspect of the post-war discourse. In fact, the treatment of the war in the media was often marked by an outspoken anti-war attitude. The attempts to come to terms with the war had distinctive pacifist undertones, which left a lasting mark on cultural memory. The new medium of film played a crucial role as it allowed to experiment with new forms of artistic expression and innovative ways to engage the audiences. An early example is Abel Gance’s (1889-1981) silent movie J’Accuse from 1919.[20] Gance had already begun shooting the film in 1917 and used 2,000 soldiers on leave as extras for battle scenes. Most of these soldiers were killed within weeks of their return to the front after the filming had ended. In a key scene at the end of the film, dead soldiers rise from a battlefield and return to the living. Gance made conscious use of this double symbolism in a revolutionary way. The soldiers who had been acting as the dead returning to the living, were now, in 1919, actual war dead that returned to the living on the screen. Gance combined this with shots of the faces of soldiers, asking the viewers directly whether their death was futile or not. This demonstrated early on the potential of films to create a direct emotional appeal to individual viewers. While J’Accuse was no straightforward pacifist film, it highlighted the relevance of individual suffering on the front and at home. In 1938, Gance produced a remake of the original film that reflected the looming danger of another great war in Europe. This time Gance made explicit connections between the suffering of the Poilus in the Great War and the obligation of the survivors to prevent a new conflict.

These themes were also picked up in other films. Erich Maria Remarque’s (1898-1970) 1928 novel Im Westen Nichts Neues (All Quiet on the Western Front) was turned into a Hollywood film in 1930. In Britain and the United States, the film received very favourable reviews and won two Oscars.[21] In Germany, however, a public controversy emerged. The far right saw the depiction of the irreverent behaviour of the protagonists and the clear anti-war message as an attack on the “honour of the German soldier”. The NSDAP organised demonstrations against cinemas that showed the film and violently broke up screenings in cities like Berlin. Under pressure from the right-wing press, the official film censor banned the film in December 1930. This in turn triggered intense public criticism from left-wing and liberal groups and eventually a heavily censored version was readmitted to public screenings in September 1931. The film was eventually banned by the Nazis in 1933. Germany was, however, not the only country where All Quiet on the Western Front caused controversy. In France, for example, scenes of German soldiers flirting with French women were censored. Fascist Italy banned the novel immediately after its publication in 1929 and prohibited the film as well. Yet, not all films focused on the futility of dying on the frontlines. Jean Renoir’s (1894-1979) 1938 La Grande Illusion (The Great Illusion) focused on the possibility of reconciliation between enemies.[22] The film depicts a group of French prisoners of war in Germany, who plan their escape from captivity. During their escape back to France, two of the protagonists find refuge with a German peasant women and a love affair develops. The message of Renoir’s film was quite clear; the war was imposed on ordinary working-class people from above, yet failed to extinguish the possibility of mutual understanding between former enemies. Against the backdrop of the international developments of the late 1930s, La Grande Illusion transported a clear pacifist message by rejecting clear distinctions between friend and foe. Films such as All Quiet on the Western Front and La Grande Illusion were embedded in a wider pacifist discourse that emerged in the interwar period. In contrast to the grand narratives of the official histories and the straightforward political uses of the war, the focus was often placed on the impact of the war on the lives of ordinary people.

This strategy was also used in other media, such as photography. Images of mutilated veterans, especially those with facial disfigurements, became powerful visual elements of the post-war discourse and were constant reminders of the destructive impact of war on the individual. In France, the so-called “Gueles Cassées” became a powerful reminder of the effects of the war on the individual. Initially, photos of these facially-disfigured veterans were taken to document the medical advances of plastic surgery. Yet in the mid-1920s, they had become public symbols of the sacrifices of ex-servicemen for the French Republic. The image of the facially disfigured veteran entered the political discourse via the medium of photography to put pressure on the government for better welfare provisions and pensions for disfigured and disabled veterans. The Gueules Cassées became synonymous with the mental and physical suffering of the veterans.[23]

The power of photography and its perceived authenticity were used in very explicit ways. The First World War produced an unprecedented number of photographs that documented every aspect of the conflict. These ranged from carefully arranged propaganda photos to snapshots made by soldiers on the frontline with pocket cameras. The latter often captured the effects of extreme violence on the individual. Images of dead and mutilated bodies were mostly censored during the war because of their negative effect on civilian morale. However, they entered the post-war debate and were used to shape the public perception of the war. In 1924, the German pacifist Ernst Friedrich published his anti-war book Krieg dem Kriege. It was designed as a photographic essay about the realities of the war and contained graphic depictions of mutilated soldiers, dead bodies and atrocities. The use of photos as the centrepiece of the book was an attempt to use their alleged authenticity to contrast with the sanitised official narratives. In 1925, an Anti-War Museum was opened in Berlin by Friedrich, using the materials collected for his book in its permanent exhibition. Krieg dem Kriege was from the outset intended as an international project and its first edition contained captions in German, English, French and Dutch. Internationally, the book was received as a powerful pacifist statement. In Germany, however, the publication caused ongoing controversy and made Friedrich a target for state repression. The reception of Krieg dem Kriege followed the established political conflict lines of the post-war discourse in Weimar Germany. In liberal and left-leaning publications, it was praised as an important documentation of the realities of the war. The far right, however, attacked Friedrich’s pacifist aims and denounced it as an attack on the honour of the German soldiers. In February 1933, after the Nazis rise to power, Friedrich was arrested and incarcerated in a “wild” concentration camp and eventually forced into exile in France.

Conclusion↑

The discourse in the European media of the interwar period was complex, multifaceted and at times contradictory and ambiguous. It reflected the political conflicts of the time, yet it also shaped them significantly. The use of new media, such as radio and film, extended the range of what could be said and represented. It made it possible to appeal directly to individual viewers and listeners while reaching millions at the same time. As we have seen, this had a profound impact on the ways the war was represented in the media. Despite the considerable attempts by governments to establish official interpretations of the war, it was often individual – sometimes fictitious – narratives that became most influential. War memoirs and novels became bestsellers in the interwar years. Veterans turned writers, such as Henri Barbusse in France, Ernst Jünger in Germany, and Edmund Blunden and Siegfried Sassoon in Britain, were seen as the authentic voices of the “trench generation”. Particularly after 1928 – the tenth anniversary of the end of the Great War – an outright “memory boom” set in. This also highlights the underlying dynamics of modern mass media. On the one hand, they satisfied a demand for certain topics to be covered. Yet, on the other hand, they also created and influenced how the public engaged with these topics by the way they represented the war. As we have seen, the radio played a crucial role in shaping modern commemorative practices, such as the two-minute silence on Armistice Day in Britain. Yet, by embedding the commemorations into a full day of programming, which included the Festival of Remembrance at the Royal Albert Hall in the evening, it also influenced how and what was remembered. The example of the Volkstrauertag in Germany highlighted, however, that the attempts to create unifying national narratives were not always successful. The media did reflect the often fragmented and politically divided nature of the public sphere. The treatment of the First World War in the media depended on the political leanings of publishers, editors and journalists. Particularly the political left denounced the Great War as a futile imperialistic conflict in which ordinary soldiers were sacrificed for the interests of politicians and capitalists. This narrative of the futility of the war was reflected in numerous films and novels, such as Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front or Abel Gance’s J’Accuse. The far right and its media outlets, on the other hand, often idealised and glorified the wartime experience. This led George L. Mosse to identify violence and a certain brutalisation as the main features of post-war discourse. We can trace both elements in the debates about the First World War, but it is difficult to determine which one dominated. Rather than making sweeping generalising statements it is important to take the specific local, regional and national circumstances into account. The representation and perception of the war were influenced by factors, such as gender, class, religion, politics and different regional experiences. The media of the interwar period reflected this multitude of attitudes and perceptions. Yet, the case studies discussed in this article also highlight the fact that the media discourse was not contained within national boundaries. In fact, public debates about the war were an inter- and transnational affair, as the translation and the circulation of films and books across borders highlights. When we take all these developments into account, it becomes clear that the structures and themes of our own contemporary discussions about the meaning of the First World War were shaped in the interwar period.

André Keil, University of Sunderland

Section Editors: Dominik Geppert; David Welch

Notes

- ↑ Mosse, George L.: Fallen Soldiers. Reshaping the Memory of the World Wars, Oxford 1994.

- ↑ For the developments in Britain, see Lawrence, John: Forging a Peaceable Kingdom. War, Violence, and Fear of Brutalization in Post-First World War Britain, in: The Journal of Modern History 75/3 (2003), pp. 557-589. For a concise argument regarding France, see Prost, Antoine: The Impact of War on French and German Political Cultures, in: The Historical Journal 37/1 (1994), pp. 209-217.

- ↑ Chalaby, Jean K.: Twenty Years of Contrast. The French and British Press During the Inter-War Period, in: European Journal of Sociology 37/1 (1996), p. 143.

- ↑ Reeves, Nicholas: Cinema, Spectatorship and Propaganda. Battle of the Somme (1916) and its Contemporary Audience, in: Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 17/1 (1997), pp. 5-28.

- ↑ Friedrich, Ernst: Krieg dem Kriege! Guerre à la Guerre! War against War! Oorlog aan den Oorlog, Berlin 1928.

- ↑ Grau, Bernhard: Bayerische Dokumente zum Kriegsausbruch und zum Versailler Schuldspruch, 1922. Issued by: Bayrische Staatsbibliothek, Historisches Lexikon Bayerns, online: https://www.historisches-lexikon-bayerns.de/Lexikon/Bayerische_Dokumente_zum_Kriegsausbruch_und_zum_Versailler_Schuldspruch,_1922 (retrieved: 26 June 2017).

- ↑ Ponsonby, Arthur: Falsehood in Wartime. Containing an Assortment of Lies Circulated Throughout the Nations During the Great War, London 1928.

- ↑ Green, Andrew: Writing the Great War. Sir James Edwards and the Official Histories, London 2004.

- ↑ Rietzler, Katharina: War as History. Writing the Social and Economic History of the First World War, in: Diplomatic History 38/4 (2014), pp. 826-839.

- ↑ Hindenburg, Paul von: Out of My Life, translated by F.A. Holt, London et al. 1920.

- ↑ Ludendorff, Erich: My War Memories 1914-1918, London 1919.

- ↑ Boraston, J.H. (ed.): Sir Douglas Haig’s Despatches. December 1915-April 1919, London et al. 1919.

- ↑ Lloyd George, David: War Memoirs of David Lloyd George, 6 volumes, London et al. 1933-38.

- ↑ Barbusse, Henri: Le Feu. Journal d’une Escouade, Paris 1916.

- ↑ Jünger, Ernst: In Stahlgewittern. Aus dem Tagebuch eines Stoßtruppführers, Berlin 1920.

- ↑ For a comprehensive history of Armistice Day in Britain, see Gregory, Adrian: The Silence of Memory. Armistice Day, 1919-1946, Oxford 1994.

- ↑ Kaiser, Alexandra: Von Helden und Opfern. Eine Geschichte des Volkstrauertages, Frankfurt am Main 2010, pp. 166-170.

- ↑ Hüppauf, Bernd: Langemarck, Verdun and the Myth of a New Man in Germany after the First World War, in: War and Society 6/2 (1988), pp. 70-103.

- ↑ Scales, Rebecca: Radio Broadcasting, Disabled Veterans, and the Politics of Recovery in Interwar France, in: French Historical Studies 31/4 (2008), pp. 643-678.

- ↑ Winter, Jay: Sites of Memory, Sites of Mourning. The Great War in European Cultural History, Cambridge 1995, pp. 15-17.

- ↑ Eksteins, Modris: All Quiet on the Western Front and the Fate of a War, in: Journal of Contemporary History 15/2 (1980), pp. 345-366.

- ↑ Winter, Jay: Remembering War. The Great War Between Memory and History in the Twentieth Century, New Haven et al. 2006, pp. 186-188.

- ↑ Houston Jones, David / Gerhardt, Marjorie: The Legacy of Gueules Cassées. From Surgery to Art, in: Journal of War and Cultural Studies 10 (2017), pp. 1-6.

Selected Bibliography

- Cornwall, Mark / Newman, John Paul (eds.): Sacrifice and rebirth. The legacy of the last Habsburg war, New York 2016: Berghahn.

- Eksteins, Modris: Rites of spring. The Great War and the birth of the Modern Age, Boston 1989: Houghton Mifflin.

- Fussell, Paul: The Great War and modern memory, Oxford 2013: Oxford University Press.

- Gerwarth, Robert: The vanquished. Why the First World War failed to end, 1917-1923, London 2016: Allen Lane.

- Gerwarth, Robert / Horne, John (eds.): War in peace. Paramilitary violence in Europe after the Great War, Oxford 2012: Oxford University Press.

- Gregory, Adrian: The silence of memory. Armistice Day, 1919-1946, Oxford; Providence 1994: Berg.

- Kaiser, Alexandra: Von Helden und Opfern. Eine Geschichte des Volkstrauertags, Frankfurt a. M. 2010: Campus.

- Lawrence, Jon: Forging a peaceable kingdom. War, violence, and fear of brutalization in post-First World War Britain, in: The Journal of Modern History 75/3, 2003, pp. 557-589.

- Mosse, George L.: Fallen soldiers. Reshaping the memory of the world wars, New York 1990: Oxford University Press.

- Prost, Antoine: The impact of war on French and German political cultures, in: The Historical Journal 37/1, 1994, pp. 209-217.

- Reynolds, David: The long shadow. The Great War and the twentieth century, London; New York 2013: Simon & Schuster.

- Ross, Corey: Mass culture and divided audiences. Cinema and social change in inter-war Germany, in: Past & Present 193/1, 2006, pp. 157-195.

- Scales, Rebecca P.: Radio and the politics of sound in interwar France, 1921-1939, Cambridge 2016: Cambridge University Press.

- Sherman, Daniel J.: The construction of memory in interwar France, Chicago; London 1999: University of Chicago Press.

- Williams, David: Media, memory, and the First World War, Montreal 2014: McGill-Queen's University Press.

- Winter, Jay: Remembering war. The Great War between memory and history in the twentieth century, New Haven 2006: Yale University Press.

- Winter, Jay: Sites of memory, sites of mourning. The Great War in European cultural history, Cambridge 2000: Cambridge University Press.