Austro-Hungarian Policies toward Muslims in Bosnia-Herzegovina, 1878-1908↑

In 1878, the Congress of Berlin convened to end the series of international conflicts that had swept across the Balkans since 1875. Among other concessions, the Ottoman Empire agreed to withdraw from the provinces of Bosnia-Herzegovina, retaining a symbolic claim of sovereignty over the province. In turn, Austria-Hungary secured the right to occupy and administer Bosnia-Herzegovina and send troops to the district of Sandžak between Serbia and Montenegro.

By occupying these former Ottoman provinces, the Habsburg Monarchy came to rule over a significant number of Bosnian Muslims, or Bosniaks, who constituted about a third of Bosnia-Herzegovina’s population. The Habsburg officials tried to overcome the initially armed resistance and to cultivate new relationships with the Muslim landowners and intellectuals. For example, Habsburg laws continued Ottoman-era practices in land ownership and agrarian relations. The Habsburg government sponsored new schools and publications specifically addressed to Bosnian Muslim audiences. In an effort to separate Bosnian Muslim affairs from the purview of Istanbul, the Austro-Hungarian administration created the position of reis-ul-ulema as the highest representative for the Islamic community in Bosnia-Herzegovina. These Habsburg efforts were not always successful at gaining local support. Tens of thousands of Muslims left Habsburg Bosnia-Herzegovina, settling mostly in the Ottoman Empire. The 1882 conscription law was met with resistance across the province, but eventually new recruits from all four major confessions (Muslims, Catholics, Jews, and Orthodox) joined the Austro-Hungarian army. A considerable number of the Bosnian ulema as well as urban elites protested against Austro-Hungarian policies as encroachments on their social position and traditional privileges. By 1900, a Bosnian Muslim movement began to demand religious and educational autonomy.

Mobilizing Muslims for the Habsburg Monarchy, 1908-1918↑

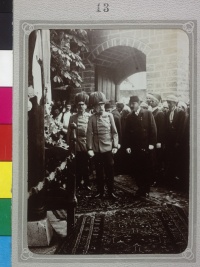

In 1908, while the Young Turk revolution took Istanbul by storm, Austria-Hungary formally annexed Bosnia-Herzegovina and thus abrogated any remaining Ottoman claim over Bosnia-Herzegovina. Following the annexation, the Habsburg administration granted religious and educational autonomy to the Islamic community of Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1909. This autonomy statute not only regulated religious affairs (such as schooling and charitable endowments), but it also revised the process for the election and appointment of the reis-ul-ulema. After a period of leadership changes, the young but well-known cleric Džemaludin Čaušević (1870-1938) was elected and, with the approval of the Habsburg emperor Franz Joseph, assumed the position of reis-ul-ulema in 1913 (continuing to hold it until 1930).

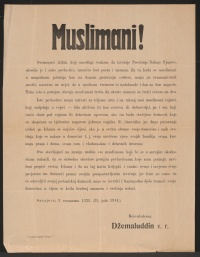

The outbreak of the First World War in the summer of 1914 led to new Austro-Hungarian efforts to mobilize Muslim soldiers under its rule and promote an image of Austria-Hungary and Germany as legitimate allies of Muslims worldwide. After entering into an alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary in August 1914, the Young Turks commanding the Ottoman government prepared to issue a declaration of jihad, or holy war on behalf of the Ottoman Empire and its allies. In November 1914, the Ottoman sultan Mehmed V (1844-1918) and the Ottoman sheyh-ul-islam, or the highest ranking authority among the ulema, issued fatwa decrees claiming that Muslims had the obligation to defend the Ottoman state and its Islamic institutions against the Entente (particularly against the British, French, and Russian empires). With Austro-Hungarian encouragement, the Bosnian reis-ul-ulema Džemaludin Čaušević issued a similar decree in December 1914. While following the pattern of the Ottoman fatwa, Čaušević’s decree specified that this declaration of jihad legitimated Muslims fighting on behalf of the Habsburg Monarchy. By trying to gain the cooperation of Islamic institutions and authorities, Germany, Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire had sweeping ambitions of mobilizing Muslims both domestically and internationally. On the ground, however, the declarations of holy war had limited and short-lived effects. In Bosnia-Herzegovina specifically, the most immediate effect of the proclamation was a brief surge in volunteering and donations to the Ottoman Red Crescent Society in 1914 and 1915.

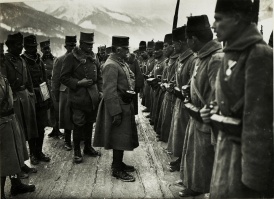

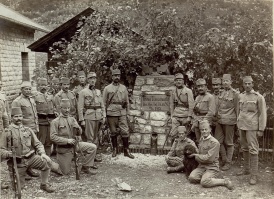

As the war dragged on, Austro-Hungarian demands on conscription of soldiers and resources continued to escalate. The already sizable number of Bosnian-Herzegovinian Muslim conscripts in the Habsburg army sharply increased, numbering some thirty-five battalions by 1916. The Habsburg military dispatched groups of Muslim soldiers to multiple fronts, from the Italian-Austrian border (at the Battles of Monte Meletta and Isonzo) to Galicia on the Eastern Front. The increasing number of Muslim soldiers in the Austro-Hungarian army also necessitated new measures. New imams were appointed to provide religious services and boost morale among Habsburg Muslim soldiers. For example, there were four military imams in the Austro-Hungarian army in 1914; during the war, at least ninety-three new imams were appointed. New dietary restrictions were supposed to be observed in preparing food for brigades with Muslim contingents, though such policies were often not followed in practice. In Zagreb, Graz, and Budapest, new Muslim places of worship were hastily constructed and opened during the First World War. On some battlefronts, separate plots were allotted for the burial of Muslim soldiers who died fighting for Austria-Hungary.

By the end of the First World War, the earlier attempts to construct a new sort of Islamic legitimacy for allied Ottoman, German, and Austro-Hungarian war efforts had collapsed. Amid the chaotic breakdown of old empires and the establishment of new nation-states, some Bosnian Muslim soldiers deserted from the Habsburg army. No longer bound to the Habsburg state, reis-ul-ulema Čaušević turned to the new Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes to seek assurances of religious autonomy for the Islamic community of Bosnia-Herzegovina. Others similarly abandoned the earlier imperial pledges emanating from Istanbul, Berlin, and Vienna and sought alternative political arrangements.

Legacies of Austro-Hungarian Policies↑

Despite the collapse of Habsburg, Ottoman, and German empires, some institutions and policies that emerged before and during the First World War continued to operate well into the interwar period. For example, the 1909 Islamic autonomy statute formed an important precedent for the broader incorporation of Muslim institutions into the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy and its successor states. In 1912, the Austrian half of the Monarchy officially recognized Islam as a state religion (Islamgesetz). After the war broke out, Hungary granted Islam the status of a legally recognized religion in 1916 (Törvénycikk az iszlám vallás elismeréséről). These laws remained in legal effect even after the formation of new republics of Austria and Hungary after 1918. Provisions guaranteeing religious rights of Muslims and the autonomy of Islamic institutions in Yugoslavia were also written into the Treaty of Saint-Germain in 1919.

Edin Hajdarpasic, Loyola University Chicago

Section Editor: Tamara Scheer

Selected Bibliography

- Jahić, Adnan: Islamska zajednica u Bosni i Hercegovini za vrijeme monarhističke Jugoslavije, 1918-1941 (The Islamic community in Bosnia-Herzegovina under the kingdom of Yugoslavia, 1918-1941), Zagreb 2010: Bošnjačka nacionalna zajednica za Grad Zagreb i Zagrebačku županiju.

- Karčić, Fikret: Džihad fetva u Bosni i Hercegovini (The jihad fatwa in Bosnia-Herzegovina), in: Godišnjak Pravnog fakulteta u Sarajevu 55, 2012, pp. 305-317.

- Neumayer, Christoph / Schmidl, Erwin A. (eds.): The emperor's Bosniaks. The Bosnian-Herzegovinian troops in the k.u.k. army. History and uniforms 1878 to 1918, Vienna 2008: Militaria.

- Šuško, Dževada: Bosniaks and loyalty. Responses to the conscription law in Bosnia and Hercegovina 1881/82, in: Hungarian Historical Review 3/3, 2014, pp. 529-559.

- Zürcher, Erik-Jan (ed.): Jihad and Islam in World War I. Studies on the Ottoman jihad on the centenary of Snouck Hurgronje's 'Holy war made in Germany', Leiden 2016: Leiden University Press.