Introduction↑

The establishment of the Armenian Patriarchate of Istanbul dates back to 1461. However, as Kevork Bardakjian notes, throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, the Armenian patriarch in Constantinople did not have jurisdiction and authority over all the Ottoman territories, he was solely the patriarch of the city.[1] The jurisdiction of the Armenian Patriarchate of Istanbul was gradually extended in the coming centuries. Through the Tanzimat reforms (1839-1876), the relations between the Ottoman state and non-Muslim communities and their internal organizations became legally more consistent and institutionalized. With the 1863 “Armenian National Constitution” (Azgayin Sahmanatrutyun Hayotz), the ambiguous framework of the millet system was replaced with written community regulations, which recognized the patriarch of Istanbul as the head of the empire’s Armenian millet.[2] The constitution introduced the concept of separating “spiritual and civic matters” and led to the establishment of representative and administrative bodies (civic and religious/spiritual councils).[3] With the 1908 Revolution, Armenian political parties largely challenged the moral and political leadership of the patriarchate. However, on the eve of the First World War, the Armenian Patriarchate of Istanbul, and more generally the clergy in the provinces, still acted as the representatives of the Armenian community and performed non-religious public roles.[4]

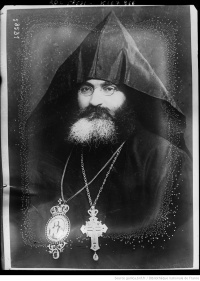

Patriarch Zaven I Der Yeghiayan (1868-1947) became the Armenian patriarch of Istanbul in 1913. He was exiled to Baghdad by the Ottoman authorities in 1916. He returned to Istanbul in early 1919 with the support of the Entente Powers. In 1922, he had to leave Istanbul as a persona non grata. His term as the patriarch coincided not only with the First World War, but also with the demise of the Ottoman Armenians and the Ottoman Empire.

Ottoman Entry to the War↑

After the declaration of mass mobilization, the Armenian Patriarchate of Istanbul received daily reports of atrocities from the provinces. Now that the promised reform in the eastern provinces was no longer a reality, the patriarchate was concerned about the fate of Armenians under wartime circumstances.[5] The patriarch’s circular of 10 November 1914 reemphasized the loyalty of the Armenians to the government by underlining the Armenian people’s commitment to the mobilization order, their agreement to all governmental directives, including war requisitioning, and more generally their willingness to make any sacrifice. With initiatives such as establishing a field hospital, opening a nursing school, and producing textiles for the army, the patriarchate sought to convince the government of the Armenians’ goodwill, but he did so in vain.

Resistance and Relief during the Genocide↑

Throughout the war, the main preoccupation of the patriarchate was to stop the spiral of violence against Armenians. Patriarch Zaven visited Minister of the Interior Mehmed Talat Pasha (1874-1921) about the matter on 21 April 1915 after he received alarming reports from Erzurum, Van, and Bitlis, along with the suspicious disarmament of Armenian conscripts in the Ottoman army. During the night of 24-25 April 1915, Istanbul’s Armenian elite, several hundred political activists, journalists, writers, lawyers, doctors, school principals, clergymen, and merchants were rounded up. The patriarch once again visited Grand Vizier Said Halim Pasha (1865-1921) and Talat. Instead of an explanation, he was counter-attacked with the statement that these were “separatists”, members of political/military organizations, which “conspired against the state”. With the announcement of the “Armenian rebellion” in Van on 28 April 1915, the authorities introduced a temporary law of deportation (27 May 1915). In early June 1915, the patriarch was quite isolated in Istanbul, as his connections to the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) had been deported. Nevertheless, throughout the summer and fall, he made appeals to political authorities including the grand vizier, the minister of justice and sects, the president of the Ottoman parliament, and Talat, the “architect of genocide”.[6]

The patriarch was unable to temper the government’s position, but he managed to inform the outside world of the Armenian people's plight. He sent unsigned reports to Bulgaria via the Italian embassy; he informed United States Ambassador Henry Morgenthau (1856-1946) thanks to Arshag Shmavonian (1860-1919), who worked at the embassy; he tried to approach European diplomats in the capital, such as the Papal Nuncio Monsignor Dolci (1867-1939), the Austro-Hungarian ambassador, Johann von Pallavicini (1848-1941), and the new German ambassador, Paul Wolff Metternich (1853-1934), who replaced Hans von Wangenheim (1859-1915).

Zaven also worked to organize a network to distribute aid to the deportees in Syria. With the help of Shmavonian, he persuaded the American Red Cross to send aid to these areas. Another active relief and information network relied on the Baghdad railway thanks to Armenian railway employees who worked on this line. The patriarchate was connected to the other end of the railway, to Mosul, through police chief Mehmed Halid (Gökçen) (1868 – ?), a converted Armenian.[7]

Dissolution of the Patriarchate and Exile↑

The Armenian Patriarchate of Istanbul was dissolved on 28 July 1916 by a decree of the Ottoman Council of Ministers.[8] The decree stipulated the merging of the catholicosates of Sis (in Adana) and Akhtamar (in Van) and transferred the authority of the patriarchates in Istanbul and Jerusalem to this new “Patriarchate-Catholicosate”.[9] On 13 August, “former Patriarch Zaven” was informed that he had to leave for Baghdad. The patriarch’s imminent exile was the logical consequence of the dissolution of the patriarchate.

Zaven started his journey on 4 September from the Haydarpaşa train station. His travels through Baghdad and Mosul, recounted in his memoir, are an important eyewitness account of the deportees in Meskene, Hamam, Sebka, Zor, Miadin, Baghdad, Mosul, Basra, and Bakuba. The patriarch was held under house arrest in Baghdad from October 1916 to early March 1917.[10] Later, he went to Mosul shortly before the British captured the city and spent the last year of the war there. During this time, he provided relief to Armenian survivors in the region with donations received from the new “patriarch-catholicos”, Sahak II, Catholicos of Cilicia (1849-1939).

Post-war Restitution↑

The Istanbul patriarchate was restored after the Mudros Armistice at the initiative of the Entente Powers. In a declaration published in November 1918, the French and British high commissioners ordered the Ottoman government to facilitate the repatriation of Greek and the Armenian survivors; to give the communities back their confiscated property, together with their bank deposits; and to release abducted women and children.[11] The patriarch returned to Istanbul on 19 February 1919. In the meantime, waves of Armenian refugees were flowing into the Ottoman capital, since general lawlessness reigned throughout the countryside. The patriarchate tried to administer the refugee crisis by establishing relief committees for orphans and exiles, opening shelters, and providing aid.

In this period, the patriarchate established an information bureau to gather documents, eyewitness accounts, statistics, and other corroborating evidence on demographic issues, persecutions, massacres, deportations, stolen property, abducted people, and the main perpetrators of the crimes in anticipation of the establishment of an international court of justice to judge those “crimes against humanity”.

Nazan Maksudyan, Freie Universität Berlin and Centre Marc Bloch

Section Editor: Erol Ülker

Notes

- ↑ Bardakjian, Kevork: The Rise of the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople, in: Braude, Benjamin / Lewis, Bernard (eds.): Christians and Jews in the Ottoman Empire. The Functioning of a Plural Society, New York 1982, pp. 89-100.

- ↑ Artinian, Vartan: The Armenian Constitutional System in the Ottoman Empire, 1839-1863. A Study of its Historical Development, Istanbul 1988. For the Turkish translation, see Artinian, Vartan: Osmanlı Devleti’nde Ermeni Anayasası’nın Doğuşu, 1839-1863, Istanbul 2004.

- ↑ Koçunyan, Aylin: The Transcultural Dimension of the Ottoman Constitution, in: Firges, P. et al. (eds.): Well-Connected Domains. Towards an Entangled Ottoman History, Leiden 2014, pp. 236-258.

- ↑ Kılıçdağı, Ohannes: Social and Political roles of the Armenian Clergy from the Late Ottoman Era to the Turkish Republic, in: Philosophy & Social Criticism 43/4-5 (2017), pp. 539-547.

- ↑ For a discussion of the reform project for seven Ottoman eastern provinces that Ottoman Grand Vizier Said Halim and the Russian chargé d’affaires Konstantin Gulkevich signed on 8 February 1914, see Kieser, Hans-Lukas / Polatel, Mehmet / Schmutz, Thomas: Reform or Cataclysm? The Agreement of 8 February 1914 Regarding the Ottoman Eastern Provinces, in: Journal of Genocide Research 17/3 (2015), pp. 285-304.

- ↑ In his recent book, Hans-Lukas Kieser used this appellation for Talat: Kieser, Hans-Lukas: Talaat Pasha. Father of Modern Turkey, Architect of Genocide, Princeton 2018.

- ↑ We understand from a coded telegram that the Ottoman authorities found out about this network in mid-1918, when the patriarch himself was in exile in Mosul. Başbakanlık Osmanlı Arşivi (BOA), Istanbul, Dahiliye Şifre Kalemi (DH. ŞFR.), 578/9, 16 April 1918; Şahin, Eyüp: Türk Polisinden Seçkin Biyografiler [Distinguished Biographies from Turkish Police], vol. 1, Ankara: Emniyet Genel Müdürlüğü Yay 2012, pp. 203-210.

- ↑ Ermeni Katoğikosluk ve Patrikliği Nizamnamesi [The Regulation of Armenian Patriarchate and Catholicosate], in: Takvim-i Vekayi 2611, 28 July 1916.

- ↑ The first article stipulated: Sis ve Ahtamar Ermeni Katoğikoslukları tevhid ve Dersaadet ve Kudüs Ermeni Patriklikleri dahi bu Katoğikosluğa ilave olunmuştur.

- ↑ The patriarch travelled from Baghdad to Mosul together with a number of Armenians. BOA, DH. ŞFR., 548/29, 15 March 1917.

- ↑ For a discussion of the role of patriarchal authorities in immediate post-war Istanbul, see Ekmekcioglu, Lerna: A Climate for Abduction, a Climate for Redemption. The Politics of Inclusion during and after the Armenian Genocide, in: Comparative Studies in Society and History 55/3 (2013), pp. 522-553. For a discussion of post-genocide Armenian existence in Istanbul in the following decades, see Suciyan, Talin: The Armenians in Modern Turkey. Post-genocide Society, Politics and History, London et al. 2016.

Selected Bibliography

- Balakian, Peter / Sevag, Aris / Balakian, Grigoris: Armenian Golgotha. A memoir of the Armenian Genocide, 1915-1918, New York 2010: Vintage Books.

- Bardakjian, Kevork: The rise of the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople, in: Braude, Benjamin / Lewis, Bernard (eds.): Christians and Jews in the Ottoman Empire. The functioning of a plural society, New York; London 1982: Holmes & Meier, pp. 89-100.

- Kévorkian, Raymond H.: The Armenian genocide. A complete history, London 2011: I. B. Tauris.

- Kieser, Hans-Lukas: Talaat Pasha. Father of modern Turkey, architect of genocide, Princeton 2018: Princeton University Press.

- Kılıçdağı, Ohannes: Social and political roles of the Armenian clergy from the late Ottoman era to the Turkish republic, in: Philosophy & Social Criticism 43/4-5, 2017, pp. 539-547, doi:10.1177/0191453716688366.

- Zaven, Der Yeghiayan / Misirliyan, Ared: My patriarchal memoirs, Barrington 2002: Mayreni Publishing.