Introduction↑

The First World War was a different experience from earlier forms of war. Both contemporaries and historians described it as a “total war” which required the mobilization of all members of society regardless of age or gender as well as extensive resource allocation for the war. The war also blurred the boundaries between the military and the civilian realms, bringing together soldiers’ experiences at the front with the daily life of people at the home front. Traditionally unarmed and non-belligerent sections of the society, most significantly women and children, were also at war.

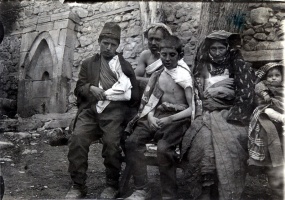

Ottoman home front experiences of the war have recently become new research areas for Ottoman historians.[1] There is new research especially on home front suffering. Large segments of society were negatively affected by mass conscription, involuntary displacement, ethnic tensions, massacres, devastated economic infrastructure, rationing, government requisitioning of grain and livestock and other catastrophic effects of the war. In parallel with the attempt to reformulate and expand the subject, scope and actors of history-writing, children have featured as legitimate partakers, actors and witnesses of Ottoman political action and experience in war.

Children were deeply engaged in every facet of the First World War. They were not only passive victims or casualties. Rather, they became active agents as wage earners, peasants and even heads of family on the home front. They directly contributed to the propaganda and mobilization effort as boy scouts, as symbolic heroes and as orphans of martyrs. They played a part in constituting the meaning of the war through their own responses and by the way in which states and societies used children as symbols of virtue, sacrifice and patriotism. Children, in the aftermath of the war, acted as the primary witnesses of the war experience as survivors and veterans. This paper discusses the variegated involvement of Ottoman children and youth, that is to say those under eighteen years of age, in the war effort with an empowering approach recognizing the agency of children and youth.

Children and Youth in Military Mobilization↑

Despite serious weaknesses, the Ottoman state succeeded in mobilizing hundreds of thousands of civilians on short notice, building an army of about 2.9 million troops.[2] Children, especially young boys, were not exempt from the war effort, combat and fighting. It is difficult to ascertain the number of underage soldiers in the Ottoman army. However, by 1917 even the best units were losing half their new recruits to desertion or sickness. A large number of boys as young as sixteen were conscripted to compensate.[3]

A major development that drew Ottoman children into mobilization was the formation of the first boy scouting organizations on the eve of the First World War. Robert Baden-Powell’s (1857-1941) Boy Scouts was met with enthusiasm in the major cities of the Empire as the perfect combination of patriotism, athleticism and skill-building for children and youth.[4] The real scouting activity began in the Ottoman Empire with the foundation of the Türk Gücü Cemiyeti (Turkish Strength Association) in 1913.[5] The paramilitary and nationalist association aimed to spread Turkism and appeal to boys’ heroism and patriotism. Soon after, the association was reorganized as the Ottoman Strength Association and institutionalized in schools in a more centralized manner – membership was obligatory for students of state schools and medreses (Muslim religious schools).[6] The curriculum envisioned military exercise and drill (both with and without arms) for pre-military age students. The ultimate goal was to open branches even in small villages to make each young boy a perfect soldier.

The heightened importance of physical education added a military dimension to general education as well. Ottoman educators decided to utilize war to create a generation of courageous and nationalist youth. In 1915, the Ministry of Education decided to include military training in the curriculum of state orphanages. 300 rifles were sent by the War Ministry to the boys’ orphanage in Kadıköy to be used for practice. The Directorate of the Orphanages claimed that boys who were trained with weapons very quickly showed obvious signs of “order and nationalist feeling” (intizam ve hiss-i milli).[7]

In 1916, the name of the scouting organization was further changed to Genç Dernekleri (Youth League). Inspired by German paramilitary youth organizations, the League became part of the War Ministry's military hierarchy.[8] Those between twelve and seventeen would belong to a group called Gürbüz (Healthy Boys) and those between seventeen and twenty would be in Dinç (Vigorous). Now every Ottoman youth including those who did not go to school had to be a member.[9] As the overwhelming majority of Ottoman children and youth were unschooled during the war years, the organization mainly targeted peasant boys of the provinces. Though they were the best conduit for reaching out to youth, the schools were now mostly closed. Thus, the League decided to use the network of village heads. The Inspectorate of the League required every provincial and district governor to establish a branch and make sure that all boys between the ages of twelve and seventeen were registered. Village headmen (muhtar) kept lists of eligible young boys and made sure they attended the activities of the League. The Youth League not only trained boys for military service, but also propagated the war cause in rural areas to overcome resistance to conscription. However, as the League trainers were drilling boys, the rumor spread that the state was forming “an army of children,” or that the state would conscript children younger than fifteen.[10] In some areas, mothers openly resisted sending their sons to League activities. In others where boys were needed for the agricultural workforce, no branch was established. Despite these limitations, the League trained about 200,000 boys over the course of the war years.

A Four-Year Break from School↑

Mass mobilization left the overwhelming majority of Ottoman children unschooled during the war years. The government first closed almost all foreign schools, including Catholic and Protestant missionary schools. Only German schools, along with some American and Alliance Israelite schools could remain open. Many private schools were also discontinued as the War Ministry refused to postpone private school teachers’ induction into military service. Other schools, such as Teachers’ College (Darülmuallimin), School of Pharmacy (Eczacı Mektebi) and School of Dentistry (Dişçi Mektebi) were also closed due to shortages of teaching staff.

The consequences were also severe for public primary and secondary schools. In the academic year 1913-1914, the number of public primary schools throughout the Empire was already low with a total of 4,486.[11] In other words, schooling was far from universal, yet it was on the rise. The war turned progress into decline. There are no equivalent statistics for the war years, but the archival records show that as school teachers were conscripted, many schools were suspended.[12] Narrative accounts also refer to the closing or simple absence of schools, especially in less urban areas.[13] The war made schooling almost obsolete.

Lack of schooling raised the middle-class concern that children were over-socialized with street life and developing delinquent behaviors. Youth criminality in the urban context had been on the agenda of Ottoman social reformers before the outbreak of the war[14] and the war then came to be perceived as a catalyst for delinquent behavior. In response, Ottoman authorities developed a critical discourse on unschooled city children. The Minister of Public Education Ahmet Şükrü Bey (1875-1926) claimed that the opening of state kindergartens for the first time in 1915 was to rescue thousands of children from socialization on the streets (sokak terbiyesi).[15]

Children as Labor Force on the Home Front↑

The combatant states, first of all, developed and promoted the idea of “mass heroism” to tap the economic resources of child laborers and consumers. Secondly, children assumed the places vacated by grown-up men. These war workers were not laboring children, but “little adults.” Teenage children were called upon to assume responsibility for absent adults and sacrifice for the nation, but they also figured as independent agents. Ottoman children between the ages of eight to sixteen were extensively involved in realms of agriculture, manufacturing and shop-keeping. Many children were employed as farm workers, as “soldiers of the soil,” since food was a necessary weapon. Indeed, school-age children were already working in agriculture extensively on the eve of World War I. However, as the war meant total mobilization for adult men, the younger population became the main labor force.

Official and semi-official organizations, founded at the instigation of the War Ministry encouraged the recruitment of women and children in the urban manufacturing sector. The Society for the Employment of Muslim Women and the Society for the Employment of Wives and Children of Veterans and Martyrs recruited formerly unemployed members of the society and secured jobs for almost 100,000 women and children.[16]

Child labor in the industrial sector also became indispensable. In the coal mines of Zonguldak the manpower shortages already evident during the Balkan Wars became worse during the World War. After 1915, those available for “unskilled” mine work were “children, old men, malingerers unfit for military service.”[17] Children in industries requiring semi-skilled work were also of vital importance. For instance, Armenian children working as laborers in the yarn factory of Adana were exempted from deportation orders until replacements could be found from among the Muslim child population.[18]

Children as Icons of Sacrifice↑

Children were used as symbols of sacrifice to mobilize the population for the war effort. They were portrayed as icons of heroism, patriotism, nationalism and ideal citizens. Wives and children of soldiers/martyrs in particular became public figures, frequently portrayed in war propaganda, moral discourse and literature as courageous, patriotic members of the nation. Children took part in official ceremonies, such as the Sultan’s inauguration anniversary or the welcoming of Wilhelm II, German Emperor (1859-1941) in Istanbul. They marched in front of soldiers, sang military songs, offered flowers to higher officials. By propagating images of children’s enthusiasm for war, the Ottoman state hoped to encourage mobilization. The nationalist spirit of children would purportedly reinforce selflessness and courage in soldiers.

Family members serving in the army transformed children’s public identity and reconstructed their relationship vis-à-vis the state. The state defined children exclusively with reference to family members in the army. Orphaned children personified war’s traumatic effects on society. They were the living legacy of the dead, symbols of sacrifice and heroism. Through material and symbolic gestures for their families, the Ottoman state paid tribute to deceased fathers. Symbolic honoring took the form of medals, memorials and ceremonies. More tangibly, soldiers’ wives and children became primary objects of state philanthropy. The “Orphans and Widows Aid Fund” (Eytam ve Eramil Sandığı) was reinforced and reorganized to ensure stipends and other benefits for the dependents of the martyrs. State subsidy for soldier families (muinsiz aile) was especially necessary to ensure enlistment and prevent desertion.[19]

Orphans of martyrs were also mobilized for pure propaganda purposes. In the emptied former Greek town of Burhaniye, the local governorship arranged the settlement of Muslim orphans in two different neighborhoods for boys and girls.[20] Each carried an identity disc indicating their age and where and how their fathers were martyred. The governor envisaged a model child colony in which nationalist and religious patriotism was built in early on and children lived as remnants of martyred heroes.

Children and Philanthropy↑

Welfare policies toward children’s services such as orphanages, clinics, and children's programs significantly increased due to and despite the emergencies of the war.[21] A large network of about twenty state orphanages (Darüleytam) was already established in late 1914 under the newly formed Directorate of Orphanages. This was both due to pressing circumstances and also thanks to the confiscation of educational and philanthropic institutions of the Entente Powers – mostly those of missionaries. The finances for orphanages came from both central and provincial treasuries. In addition, a special “tax for the children of the martyrs” (evlad-ı şüheda vergisi) was introduced to meet the increasing expenditures of orphanages. In two years, there were sixty-nine orphanages spreading to the entire geographical span of the Empire. Still, these “emergency orphanages” could not cope with the ever-increasing number of orphans. In order to limit the potential applicants, the Directorate only accepted those whose fathers died or wounded during combat.[22] Still in 1917, there were about 12,000 orphans in eighty-five orphanages.

The orphanages were run by government officials. In addition, the privately organized and financed Children’s Protection Society (Himaye-i Etfal Cemiyeti, or CPS) and the Red Crescent Society (Hilal-i Ahmer Cemiyeti) were also influential. The CPS was founded towards the end of the war by a group of doctors, businessmen, lawyers and other bureaucrats to advance the cause of children’s health and welfare. The Red Crescent Society provided shelter and material assistance to growing numbers of orphaned, homeless and displaced children.[23]

Displaced Children↑

The war forcefully displaced and uprooted a great number of children. Hundreds of thousands of child victims of the Armenian genocide predominantly fell under this category. Many girls, and sometimes boys, were taken by Muslim state officials, military personnel and local Muslims into households to be used as farm laborers, domestic helpers, concubines or wives. The Ministry of the Interior also transferred hundreds of Armenian orphans from Anatolia to Istanbul through the “Society for the Employment of Muslim Women” to be placed in selected Muslim households or employed in factories, workshops, ranches and small businesses.[24] Many Armenian orphans ended up in Ottoman state orphanages. Frequently assigned Turkish names and circumcised, they were raised as Muslims.[25]

In the post-war period, displacement took the reverse direction. The new Ottoman government was supportive of repatriation, ordering that all “Christian girls and children who are forcefully (cebren) kept in Muslim households be freed and returned to their relatives.”[26] Armenian patriarchal authorities launched a campaign of “orphan-gathering” (vorpahavak) to find, liberate and reintegrate Armenian children who had spent the last few years in Muslim households and orphanages.[27] The recovery of lost children was considered crucial for the national regeneration of the Armenian community, decimated by genocide, war and displacement. However, as the Turkish nationalist movement took shape, public sentiment became increasingly anti-Armenian. Armenians were now accused of kidnapping and forcing Muslim children to “confess” their Armenian origin.[28]

The ability of children to learn new languages, religions and identities saved many lives during the genocide.[29] Armenian orphans were treated as nobody’s children with a serious potential for “recycling.” It was assumed that orphans could easily embrace a new identity, such as a Protestant or a Muslim Turk or Kurd. Since population was the highest measure of national power and prestige in the first half of the 20th century, nationalist population politics turned children into a commodity to be possessed, kidnapped or reshaped.

The other large-scale and long-distance Ottoman child-displacement caused by the war was the sending of about a thousand orphan boys in 1917 and 1918 to Germany to be apprenticed in crafts, mines and farms.[30] The transfer aimed to provide vocational training through apprenticeship in foster-care arrangements. The political and diplomatic proximity between two empires partially explains the motivation behind the project. However, wartime emergencies and difficulties played a more decisive role. Sheltering, feeding and educating an enormous number of orphan children was an urgent and pressing problem for the Ottoman government. In this context, German master craftsmen and mine-owners became outlets to export this “surplus” child population. Boys were chosen by representatives of the Ottoman Ministry of Education and the Orphanage Administration (Darüleytam Müdüriyeti) based on voluntary application. The state-supported German association, the Deutsch-Türkische Vereinigung (German-Turkish Association, or DTV) was the responsible body for the entire organization. Despite considerable enthusiasm in the beginning, the DTV claimed that the Ottoman government was sending anyone who volunteered without a medical examination and no consideration of vocational qualifications. Once in Germany orphan boys were also unhappy at their places of work, complaining that they did not volunteer to become mine workers. As destitute, uprooted, foreign boys, they also suffered from exploitation, discrimination and stereotyping in a migrant worker’s situation.

Children and the Future of the Nation↑

In the second half of the 19th century, nation-states and nationalist ideologies posited children and youth as the “future of the nation.” Especially during World War I, children's lives were praised as the rejuvenating source for the nation's future. In the case of France or Britain, the nation appeared as an indispensable link between children and war: children labored and sacrificed for the nation. However, the multi-national structure of the Ottoman Empire and the contested meaning of “nation” complicated definitions of what Ottoman children represented and stood for.[31] "The child" was not a universal category throughout the Ottoman Empire, one that transcended the particularism and ethno-religious differentiation that characterized the polity. Rather communities socialized children into separate nationalist, ethnic and religious identities, as the central government more strongly emphasized the Muslim and Turkic identity of the state.

Nationalist propaganda exacerbated tensions between children of different cultures. Although inter-cultural conflicts preceded the war, World War I led all communities to fight different battles and dream different futures. Inter-ethnic boy gang fights in multi-ethnic cities of the Empire were a harbinger of the Empire’s final dissolution.[32] Children took part in nationalist rivalries in the appropriation of a street, a quarter, a city. A striking example of this bitter war, the Greek press claimed that Greek children were active in resisting the order of deportation from Ayvalık, throwing stones at the gendarmes with slingshots. As a punishment, their hands were amputated by Muslim boy gangs.[33] Many children took part in acts of violence against their defined others based on “nationalistic sensitivities.”

Conclusion↑

Ottoman children acquired new identities during the war years and discovered new forms of agency, either in the form of throwing stones at security forces, getting into a fight with neighbors or enrolling in the boy scout organizations which made them more visible and active in the public space. Interestingly, national identity was formed upon an infantilized understanding of the nation as a child in numerous successor states in the Middle East. There is a lot of imagery from the 1920s Turkey, for instance, that portrays the new state metaphorically as a child. Nationalist intellectuals and statesmen of the interwar decades probably leaned on their own multinational childhoods as the children of a dismantling Ottoman Empire, who were introduced to nationalism for the first time as imperial subjects. Those who founded the nation-states of the post-Ottoman era were precisely those who had grown up and were children during late Ottoman times, particularly World War I. Ironically, in all these nation-states, the elites saw their people as immature, ignorant, innocent children (masses) to be raised with proper inculcation, despite their own childhood experiences as empowered and active agents.

Nazan Maksudyan, Istanbul Kemerburgaz University

Section Editors: Mustafa Aksakal; Elizabeth Thompson

Notes

- ↑ See Beşikçi, Mehmet: Ottoman Mobilization of Manpower in the First World War: Between Voluntarism and Resistance, Leiden 2012; Akın, Yiğit: War, Women, and the State: The Politics of Sacrifice in the Ottoman Empire during the First World War, in: Journal of Women's History 26/3 (2014), pp. 12-35.

- ↑ Larcher, Maurice: La Guerre Turque dans la Guerre Mondiale, Paris 1926.

- ↑ Nicolle, David/Ruggeri, Raffaele: The Ottoman Army 1914-1918, London 1994, p. 18.

- ↑ Brummett, Palmira Johnson: Image and Imperialism in the Ottoman Revolutionary Press, 1908-1911, Albany 2000, p. 199.

- ↑ Toprak, Zafer: II. Meşrutiyet Döneminde Paramiliter Gençlik Örgütleri [Paramilitary Youth Organization in the Second Constitutional Period], in: Tanzimattan Cumhuriyet'e Türkiye Ansiklopedisi [Encyclopedia of Turkey from the Tanzimat to the Republic], Istanbul 1985, pp. 531-536.

- ↑ Beşikçi, Ottoman Mobilization 2012, pp. 226-232

- ↑ Başbakanlık Osmanlı Arşivi (BOA) [Primary Ministry's Ottoman Archives] in Ankara, BOA MF.MKT., 1212/63, 02/Z/1333 (11.10.1915).

- ↑ Köroğlu, Erol: Ottoman Propaganda and Turkish Identity: Literature in Turkey During World War I, London 2007, pp. 59-61.

- ↑ BOA, MF.MKT., 1215/23, 28/Ca/1334 (02.05.1916).

- ↑ Sarısaman, Sadık: Birinci Dünya Savaşında İhtiyat Kuvveti Olarak Kurulan Osmanlı Genç Dernekleri [Ottoman Youth League that was founded as Uncommitted Force in World War 1], in: Ankara Üniversitesi Osmanlı Tarihi Araştırma ve Uygulama Merkezi Dergisi 11 (2000), pp. 439-501.

- ↑ Alkan, Mehmet Ö.: Tanzimat'tan Cumhuriyet'e Modernleşme Sürecinde Eğitim İstatistikleri, 1839-1924 [Statistics of Education from the Tanzimat to the Republic, 1839-1924], Ankara 2000, pp. 165-166.

- ↑ BOA, MF.MKT., 1207/38, 19/Ca/1333 (4.5.1915); BOA, MF.MKT., 1227/48, 23/Ş /1335 (14.6.1917).

- ↑ Mehmet Akdokur (born in 1910 in Kilis) tells that he spend his childhood mostly with threshing and later as an apprentice to a carpenter. Neither he nor his elder brother ever attended school. Tan, Mine et. al. (eds.): Cumhuriyet'te Çocuktular [They were Children of the Republic], Istanbul 2007, p. 306-309.

- ↑ See Maksudyan, Nazan: Children as a Transgressors in Urban Space: Delinquency, Public Order and Philanthropy in the Ottoman Reform Era, in: François, Aurore/Massin, Veerle/Niget, David (eds.): Expertise and Juvenile Violence, 19th-21st century, Louvain 2011, pp. 21-39.

- ↑ Fortna, Benjamin: The Kindergarten in the Ottoman Empire and the Turkish Republic, in: Wollons, Roberta Lyn (ed.): Kindergartens and Cultures: The Global Diffusion of an Idea, New Haven 2000, pp. 251-73.

- ↑ Karakışla, Yavuz Selim: Women, War and Work in the Ottoman Empire: Society for the Employment of Ottoman Muslim Women, 1916-1923, Istanbul 2005.

- ↑ Quataert, Donald: Miners and the State in the Ottoman Empire: The Zonguldak Coalfield, 1822-1920, New York 2006, p. 145.

- ↑ BOA, DH.ŞFR., 259/55-A, 03/Za/1333 (14.09.1915).

- ↑ Özbek, Nadir: Cumhuriyet Türkiyesi'nde Sosyal Güvenlik ve Sosyal Politikalar [Social Security and Social Policy in Republican Turkey], Istanbul 2006, p. 31.

- ↑ BOA, DH. UMVM., 136/61, 29/R/1334 (04.02.1916).

- ↑ See Maksudyan, Nazan: Orphans and Destitute Children in Late Ottoman History, Syracuse 2014.

- ↑ BOA, DH.UMVM., 70/40, 03/Ra/1334 (08.02.1916).

- ↑ Libal, Kathryn R.: The Children’s Protection Society: Nationalizing Child Welfare in Early Republican Turkey, in: New Perspectives on Turkey 23 (2000), pp. 53-78.

- ↑ For further information, See Karakışla, Women, War and Work 2005.

- ↑ Dinamo, Hasan İzzettin: Öksüz Musa. Istanbul 2005.

- ↑ BOA, DH.ŞFR., 92/196, 15/M/1337 (21.10.1918); BOA, DH.ŞFR., 95/212, 19/R/1337 (23.12.1918).

- ↑ Ekmekcioglu, Lerna: A Climate for Abduction, a Climate for Redemption: The Politics of Inclusion during and after the Armenian Genocide, in: Comparative Studies in Society and History 55/3 (2013), pp. 522-553.

- ↑ Kévorkian, Raymond: The Armenian Genocide: A Complete History, New York 2011, pp. 760-62.

- ↑ Zahra, Tara: Lost Children, Reconstructing Europe's Families after World War II, Cambridge 2011.

- ↑ See Maksudyan, Nazan: Refugee Ottoman Orphans in Germany during the First World War. In: Bley, Helmut / Kremers, Anorthe (eds.): The World During the First World War. Essen 2014, pp. 151-166.

- ↑ The experience of children in the Ottoman Empire largely resembled that in the Habsburg Empire. See Healy, Maureen: Vienna and the Fall of the Habsburg Empire: Total War and Everyday Life in World War I, Cambridge 2004, pp. 211-214.

- ↑ Greek children were reported to throw stones (taşa tutmak) at Muslim children and use derogatory language (tezyif ve tahkir). BOA, MV, 215/129, 27/Ş/1337 (27.05.1919).

- ↑ BOA, DH.ŞFR., 49/2, 27/S/1333 (14.01.1915).

Selected Bibliography

- Akin, Yiğit: War, women, and the state. The politics of sacrifice in the Ottoman Empire during the First World War, in: Journal of Women’s History 26/3, 2014, pp. 12-35.

- Beşikçi, Mehmet: The Ottoman mobilization of manpower in the First World War. Between voluntarism and resistance, Leiden 2012: Brill.

- Ekmekcioglu, Lerna: A climate for abduction, a climate for redemption. The politics of inclusion during and after the Armenian Genocide, in: Comparative Studies in Society and History 55/3, 2013, pp. 522-553.

- Fortna, Benjamin: The kindergarten in the Ottoman Empire and the Turkish Republic, in: Wollons, Roberta Lyn (ed.): Kindergartens and cultures. The global diffusion of an idea, New Haven 2000: Yale University Press, pp. 251-273.

- Gencer, Yasemin: We are family. The child and modern nationhood in early Turkish republican cartoons (1923-28), in: Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 32/2, 2012, pp. 294-309.

- Georgeon, François / Kreiser, Klaus: Enfance et jeunesse dans le monde musulman, Paris 2007: Maisonneuve & Larose.

- Köroǧlu, Erol: Ottoman propaganda and Turkish identity. Literature in Turkey during World War I, London 2007: I. B. Tauris.

- Libal, Kathryn R.: The Children’s Protection Society. Nationalizing child welfare in early republican Turkey, in: New Perspectives on Turkey 23, 2000, pp. 53-78.

- Maksudyan, Nazan: Children as transgressors in urban space. Delinquency, public order and philanthropy in the Ottoman Reform Era, in: François, Aurore / Massin, Veerle / Niget, David (eds.): Violences juvéniles sous expertise(s), XIXe-XXIe siècles (Expertise and juvenile violence, 19th-21st century), Louvain-la-Neuve 2011: Presses universitaires de Louvain, pp. 21-39.

- Maksudyan, Nazan: Refugee Ottoman orphans in Germany during the First World War, in: Bley, Helmut / Kremers, Anorthe (eds.): The world during the First World War. Perceptions, experiences and consequences, Essen 2014: Klartext, pp. 151-166.

- Maksudyan, Nazan: Orphans and destitute children in the late Ottoman Empire, Syracuse 2014: Syracuse University Press.

- Sarısaman, Sadık: Birinci Dünya Savaşı Sırasında İhtiyat Kuvveti Olarak Kurulan Osmanlı Genç Derneği (The foundation of the Ottoman youth organization as a military reserve force during the First World War), in: Ankara Üniversitesi Osmanlı Tarihi Araştırma ve Uygulamaları Dergisi 11, 2000, pp. 439-501.

- Tan, Mine Göğüş (ed.): Cumhuriyet'te çocuktular, Istanbul 2007: Boğaziçi Üniversitesi Yayınevi.