Introduction↑

The image of Canadian women lovingly supporting their men at war was an important propaganda tool and morale-booster during the Great War (1914-1918), but women’s wartime activities extended far beyond waiting and worrying. The Great War did not fundamentally transform women’s roles in Canadian society at large, nor did it “liberate” them in any enduring sense. It did, however, accelerate certain trends, such as the movement toward woman suffrage, or women’s entry into new forms of paid employment. It also transformed some women’s lives on a personal level, as they adjusted to the temporary or permanent absence of husbands, fathers, sweethearts, and friends. As women of many combatant nations found, the war offered women a chance to make public – and publicly approved – contributions to the national and imperial cause, and placed their actions under close community surveillance.[1] It disrupted existing relationships, forged new ones, sank some women into despair, and gave others a chance to tackle fulfilling new roles and turn their hands to various forms of paid and unpaid labour. Canadian women’s individual experiences of the Great War were as diverse as Canadian women themselves. At the same time, Canadian women shared with men and women in all the combatant nations the anxiety and grief of the war years, and the desire to commemorate the war’s sacrifices at its end.[2]

Position of Women in Canadian Society and Economy↑

Canadian women’s experiences of the Great War were deeply shaped by the social and economic context of the Victorian and Edwardian periods which the war brought to such a shocking conclusion. Canadian women were vital contributors to household and national economies in this period. Through childrearing and managing their households they played key roles in family life – roles celebrated and bolstered by a still-prevalent middle-class Victorian ideology of men’s and women’s “separate spheres” of life. Despite the discourse of women devoting themselves solely to childrearing and housekeeping, many women worked for wages. The 1911 census recorded 98,128 female servants, 20,357 female dressmakers and seamstresses, and 5,269 women working in clothing factories; teaching and nursing were other common forms of female waged labour.[3] More than half the Canadian population lived in rural areas, and farm women not only worked inside their homes, but also engaged in gardening, dairying, and other outdoor work to supplement the family diet and income. Women’s work managing and stretching wages was particularly crucial to the well-being of urban working-class families in large industrialized cities like Montreal, Toronto, and Winnipeg.[4]

Middle-class women had been actively agitating since the later 19th century for a variety of social reforms and by 1914 had successfully pressured politicians to enact important legislation in areas such as public health and child labour. At the same time, small but growing numbers of women were attending Canadian universities: by 1900, 11 percent of post-secondary students in Canada were women; the figure would rise to 14 percent by 1919-20.[5] Middle-class women embraced the era’s propensity to join together in clubs, societies, and associations, often religious- or reform-based. By 1914, the broader reform movement, rooted in a maternalist approach to feminism, had largely coalesced around the issue of woman suffrage, with proponents arguing that voting women would clean up the worst social problems of Canadian society.[6] Since women already played active (if often unheralded) roles in Canada’s economy and society when the Great War broke out, they continued to do the same under wartime conditions. However, growing male labour shortages and the anxiety-filled context of wartime earned their efforts a new level of appreciation from Canadian society at large.

Diverse Responses↑

Canada in 1914 was a geographically vast, Christian, white settler colony of the British Empire. These characteristics combined to ensure that the majority of its populace, including its women, responded with patriotic fervour to the British declaration of war. Yet, thanks to early settlement patterns and a pre-war surge of immigration, the population was ethnically, linguistically, and religiously diverse, shaped by the rural-urban divide and socioeconomic class, and influenced by the terrain and resources of its many distinct regions. Canadian women’s individual experiences of, and responses to, the Great War were therefore shaped by ethnicity, region, religion, language, and class in important ways.[7]

Many socially and politically-engaged white, middle-class Canadian women saw the war as an opportunity to demonstrate their good citizenship. They hoped thereby to win the right to wider participation in Canadian public life, particularly the right to vote (as discussed above). These female leaders – women like prominent reformer and suffragist Nellie McClung (1873-1951) – believed, much like the British suffragettes under Emmeline Pankhurst (1858-1928), that their ultimate cause would be advanced by channelling their talents and energies into the war effort.[8] Like their sisters in other combatant countries, hundreds of thousands of middle-class Canadian women threw themselves into unpaid war work for a wide range of organizations, seeing this as a socially acceptable avenue of service and one of the few tangible ways in which they could support and uphold their male relatives and friends in the fighting forces. Social surveillance by friends and neighbours encouraged these women to be seen “doing their bit” for the war effort, even when war weariness or personal disinclination may have urged a different course.[9]

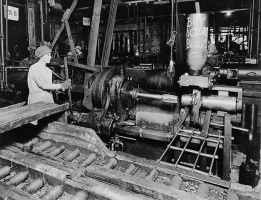

Although working-class women in Canada’s industrialized cities also did voluntary war work, they more often took up the opportunities afforded by male labour shortages and moved into factory work in ways that social convention deemed less appropriate for middle-class women. Young working-class women had a long history of supplementing family incomes through paid labour, and they made the most of wartime necessity to seek positions in munitions work, take up factory jobs normally closed to women, and abandon jobs with particularly poor working conditions and low wages (such as domestic service) in favour of better conditions elsewhere. Although male unions demonstrated ambivalence and occasional hostility toward this flood of female labourers, women workers embraced labour unions and both groups frequently worked together to try to achieve workplace gains. Women workers tended to be unmarried younger women, but by 1918 married women accounted for up to one-third of women workers in the provinces of Ontario and Quebec, the centre of Canadian industrial production.[10]

Geography shaped women’s wartime opportunities in important ways. Clerical work (for example, in Canadian banks) also attracted women workers during the war, and unlike factory work which was heavily concentrated in central Canada, clerical opportunities were available in urban areas across the country.[11] Meanwhile, rural women’s responses to the war were constrained by their isolation – particularly so on the vast farms of the western prairies. Wives and daughters struggled to compensate for the deficiency of sons and hired hands on the farm through their own increased labour, while also providing money and goods to war charities. Some young rural women continued pre-war trends in rural depopulation by moving to urban areas in search of paid work, while young urban women were recruited to supply labour in rural areas (especially at harvest time) through schemes like the Farmerettes.[12] Natural resources also shaped women’s opportunities and responses: late in the war the Red Cross enlisted women volunteers to wade through bogs along the Pacific and Atlantic coasts in search of sphagnum moss, a naturally-occurring substitute for the increasingly scarce absorbent cotton needed in bandages.[13]

Not all Canadian women supported the war, or were given the opportunity to do so. Prominent examples include pacifist, French Canadian, and visible minority women. The war called into question the loyalty of recent immigrants from enemy countries, and in response the federal government registered 80,000 “enemy aliens” – Canadians of German and Austro-Hungarian extraction. 8,000 enemy aliens were interned during the war in a network of camps, on the grounds that they were security threats; women and children were among them.[14] Even those women who were not interned faced suspicion and persecution from their neighbours, or the internment of a male relative.

In Western Canada, female and male members of Canada’s historic peace churches (Mennonites, Hutterites, and Doukhobours among them) maintained their traditional pacifism in the face of war,[15] while some women tried to uphold their pre-war feminist pacifist beliefs after 1914. Both groups faced powerful social pressures, the threat of ostracism, and sometimes active persecution from the wider Canadian community. Many pre-war feminists set aside their pacifism after 1914, often to support enlisted relatives or out of a belief in the justice of the British cause. This left committed feminist pacifists to form a tiny minority of dissent in Canada. They were nonetheless linked to a wider international movement to negotiate a peaceful end to the conflict, and Canadian Julia Grace Wales (1881-1957) earned a certain amount of international fame through her wartime peace activism.[16]

In the predominantly French-Catholic province of Quebec, many women shared in the broad French-Canadian antipathy to what they considered a British imperial war with little relevance for Canada, and were correspondingly somewhat less enthusiastic contributors to the war effort than their English-Canadian counterparts.[17] Meanwhile, visible minorities including Japanese- and African-Canadian men were either discouraged or actively barred from enlisting in the Canadian Expeditionary Force until by mid-1916 declining enlistment rates forced a re-evaluation of this policy. Women and men within these ethnic communities, as well as Indigenous Canadians, actively contested the prevailing conception of the conflict as a “white man’s war” and attempted to collectively assert their citizenship in the ways open to them. These included contributing money and goods to nationally prominent war charities like the Canadian Red Cross and Canadian Patriotic Fund, which framed contributions to their coffers as a form of alternative service for those unable to fight.[18]

Women at War↑

Canada’s geographical distance from the battlefields of Europe limited its citizens’ wartime contact with the fighting forces: once Canadian soldiers crossed the Atlantic Ocean, they could not return to Canada unless they were medically discharged from the army. Many women wished to be as close as possible to their husbands, sons or brothers, so Britain was flooded during the war years by Canadian women ranging from wealthy Montreal philanthropist Lady Julia Drummond (1861-1942) and middle-class officers’ wives, to women of more modest means who applied to the Patriotic Fund for a steerage class ticket. Often arriving in Britain with children in tow, they might see enlisted loved ones on occasion or simply satisfy their curiosity by getting a little closer to the battlefields. These thousands of Canadian women in Britain eventually constituted an important pool of voluntary labour for the Canadian Red Cross’ overseas operations, as well as for British war charities and voluntary organizations.[19] Canadian journalist and Canadian Red Cross hospital visitor Mary Macleod Moore (1871-1960) turned her eyewitness experiences in Britain and France into a series of articles for the popular press, and wrote The Maple Leaf’s Red Cross, a small book detailing how Canadian women’s war work on the home front was helping Canadian soldiers overseas.[20]

Canadians’ traditional Victorian views of appropriate gender roles also limited the ways in which women were allowed to participate in the national war effort. Combat roles for women were never considered, even in the face of worrisome declines in enlistment rates by 1916. Instead, after a bitterly fought general election, in 1917 the federal government began conscripting men for military service.[21] When a small group of Toronto women formed themselves into a quasi-military home guard unit early in the war in an effort to release men for military service, they faced serious social disapproval and were quickly forced to disband.[22]

Although wartime discourse framed many activities as home front equivalents of fighting,[23] the closest Canadian women came to the trenches of Europe was through nursing. Canada was unique within the British Empire in enlisting its military nurses as members of the Canadian army itself (the better to control them): their rank of lieutenant and higher wages than other nurses made them objects of envy, although the British nurses with whom they sometimes worked occasionally looked down upon these mere “colonials.” This military status put double pressure on the nurses, as they were held to the highest standards as both ladies and officers. Impeccable behaviour on both counts was deemed necessary by their superiors, in order to defuse the challenges to contemporary gender norms posed by women in the army, and women in intimate contact with men’s bodies. Approximately 2,500 Canadian Nursing Sisters served in Britain, France, and the Mediterranean as members of the Canadian Army Medical Corps, both healing and witnessing the destruction of war.[24]

An estimated 2,000 female Canadian Voluntary Aid Detachment members (VADs) provided semi-trained care and tackled the dirtiest and most menial of nursing tasks both in Canada and abroad, on a voluntary basis. They were not, however, allowed to serve in Canadian military hospitals overseas – Margaret MacDonald (1873-1948), matron of Canada’s military nurses, refused to allow her highly trained nurses’ skill and status to be diluted by VAD labour. Instead, Canadian VADs overseas served in British military hospitals, joined there by trained Canadian nurses. Also, many hospital-trained Canadian nurses not selected for the Canadian Army Medical Corps instead nursed overseas for the British Red Cross, Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service, or American Red Cross.[25]

Women’s Labour at Home↑

Canadian women’s greatest contribution to the national war effort was their labour on the home front. Hundreds of thousands of women provided much-needed paid labour on farms, in factories, and in offices across the country, as discussed above. The women workers interviewed in the engaging documentary And We Knew How to Dance make it clear that many young women of the Great War period took pride in this opportunity to show that they could do the same jobs men had traditionally done.[26] However, the majority of Canadian women – particularly if they were middle-class, married, or living in a rural area – made their contribution to the war effort through unpaid voluntary labour for a wide variety of war charities and women’s organizations. Among the most prominent were the Canadian Patriotic Fund, the Canadian Red Cross, the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire (IODE), the rural Women’s Institutes, the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA), and denominationally-based church groups (particularly Anglican, Methodist, and Presbyterian). Each organization had its own objectives, but most engaged women in raising money or producing goods for use by the men of the Canadian Expeditionary Force overseas. These medical supplies and accompanying “comforts” – which ranged from hand-knit socks and sweaters to reading material, maple sugar, and tobacco – boosted morale among the recipients and gave the women who provided them a valuable sense of connection to their loved ones abroad. This was especially true for women involved in funding or packing food parcels for Canadian Prisoners of War.[27]

Women’s voluntary labour also had enormous economic value. The money women raised and the supplies they produced (collectively estimated to be in the hundreds of millions of dollars),[28] constituted a pool of voluntary taxes and free labour which financially supported soldiers’ dependent wives and children, provided a broad range of medical supplies and equipment for the Canadian Army Medical Corps, and encouraged fellow citizens to buy government war bonds. Women’s voluntary work thereby freed an already financially-overburdened federal government from the full responsibility to pay for these things itself. The fact that some of these roles would be taken over by the government in the Second World War attests to the defects inherent in such reliance on voluntarism – defects which included charitable competition, overlapping mandates, and an invasive scrutiny of the household management skills of soldiers’ dependents. Nonetheless, contemporary Canadians praised women’s voluntary work as a crucial element of the Canadian war effort, and women exhibited pride in their war work.[29]

Despite their preoccupation with the war, middle-class women did not completely abandon their pre-war goals. In fact, the cause of universal woman suffrage was considerably advanced in 1916 when the western provinces of Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta gave women the provincial franchise, and again in 1917, when British Columbia and Ontario did likewise. 1917 brought further milestones: Canadian women were granted suffrage at the federal level for the first time, while Louise McKinney (1868-1931) and Roberta MacAdams (1880-1959) – the latter a serving Canadian Nursing Sister – were elected to the Alberta legislature, the first two women elected to a legislature not only in Canada but in the entire British Empire.[30] The federal Wartime Elections Act represented an incomplete victory, since it only enfranchised women with male relatives serving in the Canadian Expeditionary Force and simultaneously disenfranchised women born in enemy countries. It was also granted for barely-concealed political reasons, in order to win votes for the governing Union Party’s pro-conscription agenda. Nonetheless, the partial achievement of federal suffrage, like the five provincial suffrage victories and the elections of McKinney and MacAdams, were seen by many observers as a direct result of the war: Canadian women, it was said, had demonstrated their worthiness for full citizenship through their enthusiastic contributions to the war effort, and been rewarded accordingly.[31] This interpretation was bolstered by a more permanent (though still partial) federal woman suffrage law enacted in 1918.[32]

Ironically, the achievement of suffrage encouraged a fragmentation of the women’s movement in post-1918 Canada, as women turned their attention back to a wide variety of reform causes of more local or personal interest. At the same time, many of the workplace gains of the war years were rolled back after the armistice, as women were encouraged or forced to give way to ex-servicemen seeking work.[33] The Great War marked a significant moment in Canadian women’s history, but there would still be many battles to fight on the road to true equality. Nonetheless, pre-war trends resumed in the post-war period, in terms of slowly increasing female participation in certain segments of the paid workforce, more women pursuing higher education, and further provincial suffrage victories.[34] Women’s skills, determination, and labour (both paid and unpaid) had contributed tremendously to the functioning of Canadian society during the Great War, and would continue to do so in the 1920s and beyond.

Sarah Glassford, University of Prince Edward Island

Section Editor: Tim Cook

Notes

- ↑ Glassford, Sarah / Shaw, Amy J.: A Sisterhood of Suffering and Service. Women and Girls of Canada and Newfoundland during the First World War, Vancouver 2012, pp. 1-24; Sangster, Joan: Mobilizing Women for War, in: Mackenzie, David (ed.): The First World War in Canada. Essays in Honour of Robert Craig Brown, Toronto 2005, pp. 175-181.

- ↑ Vance, Jonathan: Death So Noble. Memory, Meaning, and the First World War, Vancouver 1997, pp. 201-220; Evans, Suzanne: Marks of Grief. Black Attire, Medals, and Service Flags, in: Glassford / Shaw, Sisterhood 2012, pp. 219-240.

- ↑ Cuthbert Brandt, Gail et al. (eds.): Canadian Women. A History, Third Edition, Toronto 2011, pp. 179-185; Ramkhalawansingh, Ceta: Women during the Great War, in: Acton, Janice / Goldsmith, Penny / Shepard, Bonnie (eds.): Women at Work. Ontario, 1850-1930, Toronto 1974, census table on p. 267.

- ↑ Kinnear, Mary: Do You Want Your Daughter to Marry a Farmer? Women’s Work on the Farm, 1922, in: Akenson, Donald H. (ed.): Canadian Papers in Rural History, volume VI, Gananoque 1988, pp. 137-153; Bradbury, Bettina: Working Families. Age, Gender and Daily Survival in Industrializing Montreal, Toronto 1993, pp. 152-181.

- ↑ Valverde, Mariana: The Age of Light, Soap and Water. Moral Reform in English Canada, 1885-1925, Toronto 2008; Cuthbert Brandt et al., Canadian Women 2011, p. 201.

- ↑ Kealey, Linda (ed.): A Not Unreasonable Claim. Women and Reform in Canada, 1880s-1920s, Toronto 1979; Cleverdon, Catherine L.: The Woman Suffrage Movement in Canada, Second Edition, Toronto 1974, pp. 11-18.

- ↑ Rutherdale pays attention to many of these differences while assessing Canadians’ patriotic responses to the war. Rutherdale, Robert: Hometown Horizons. Local Responses to Canada’s Great War, Vancouver 2004.

- ↑ McClung, Nellie L.: In Times Like These, Toronto 1915; Cuthbert Brandt et al., Canadian Women 2011, pp. 264-267,

- ↑ Szychter, Gwen: The War Work of Women in Rural British Columbia. 1914-1919, in: British Columbia Historical News 27 (1994), p. 8; Glassford, Sarah: The Greatest Mother in the World. Carework and the Discourse of Mothering in the Canadian Red Cross Society during the First World War, in: Journal of the Association for Research on Mother 10/1 (2008), p. 222.

- ↑ Sangster, Mobilizing 2005, p. 168.

- ↑ Street, Kori: Patriotic, Not Permanent. Attitudes about Women’s Making Bombs and Being Bankers, in: Glassford / Shaw, Sisterhood 2012, p. 149.

- ↑ Sangster, Mobilizing 2005, pp. 173ff; Wilde, Terry: Freshettes, Farmerettes, and Feminine Fortitude at the University of Toronto during the First World War, in: Glassford / Shaw, Sisterhood 2012, pp. 87f.

- ↑ Riegler, Natalie: Sphagnum Moss in World War I. The Making of Surgical Dressings by Volunteers in Toronto, Canada, 1917-1918, in: Canadian Bulletin of Medical History 6 (1989), pp. 27-43.

- ↑ Cuthbert Brandt et al., Canadian Women 2011, p. 164; Waiser, Bill: Wartime Internment, in: Hallowell, Gerald (ed.): The Oxford Companion to Canadian History, Don Mills 2004, p. 651.

- ↑ Shaw, Amy J.: Crisis of Conscience. Conscientious Objection in Canada during the First World War, Vancouver 2009, pp. 43-71.

- ↑ Warne, R. R.: Nellie McClung and Peace, in: Williamson, Janice / Gorham, Deborah (eds.): Up and Doing. Canadian Women and Peace, Toronto 1989, pp. 35-47; Roberts, Barbara: Women Against War, 1914-1918. Francis Beynon and Laura Hughes, in: Williamson / Gorham, Up and Doing 1989, pp. 48-65; Roberts, Barbara: “Why Do Women Do Nothing to End the War?” Canadian Feminist Pacifists and the Great War, Ottawa 1985; McLean, Lorna R.: “The Necessity of Going.” Julia Grace Wales’s Transnational Life as a Peace Activist and Scholar, in: Carstairs, Catherine / Janovicek, Nancy (eds.): Feminist History in Canada. New Essays on Women, Gender, Work, and Nation, Vancouver 2013, pp. 77-95.

- ↑ Morton, Desmond: Fight or Pay. Soldiers’ Families in the Great War, Vancouver 2004, pp. 118f.

- ↑ Walker, James W. St G.: Race and Recruitment in World War I. Enlistment of Visible Minorities in the Canadian Expeditionary Force, in: Canadian Historical Review 70/1 (1989), pp. 1-26; Rutherdale, Hometown 2004, pp. 98, 105ff; Norman, Alison: In Defense of the Empire. The Six Nations of the Grand River and the Great War, in: Glassford / Shaw, Sisterhood 2012, pp. 29-50.

- ↑ Vance, Jonathan: Maple Leaf Empire. Canada, Britain, and Two World Wars, Don Mills 2012, p. 86; Library and Archives Canada: RG 24–C–1– a “Transportation of Soldiers’ Wives and Families from Overseas to Canada.”

- ↑ Macleod Moore, Mary: Our Doctors and Nurses in War Time, in: Saturday Night Magazine, 4 May 1918; Macleod Moore, Mary: Somewhere in France. The Veil Lifted, in: Saturday Night Magazine, 26 January 1918; Macleod Moore, Mary: The Maple Leaf’s Red Cross. The War Story of the Canadian Red Cross Overseas, London 1919.

- ↑ Granatstein, J. L. / Hitsman, J. M.: Broken Promises. A History of Conscription in Canada, Toronto 1977, pp. 60-104.

- ↑ Glassford / Shaw, Sisterhood 2012, p. 15.

- ↑ Morton, Fight 2004, illustration following p. 204; Quiney, Linda: Gendering Patriotism. Canadian Volunteer Nurses as the Female “Soldiers” of the Great War, in: Glassford / Shaw, Sisterhood 2012, pp. 103-125.

- ↑ Numbers of overseas CAMC nursing sisters vary by source: Matron Margaret Macdonald counted 2,504 overseas members, and official war historian A. F. Duguid only 2,411. Mann, Susan: Margaret Macdonald. Imperial Daughter, Montreal et al. 2005, p. 224, n. 1. On military nursing see: Allard, Geneviève: Des anges blanc sur le front. L’expérience de guerre des infirmières militaires canadiennes pendant la Première Guerre Mondiale, in: Bulletin d’histoire politique 8/2-3 (2000), pp. 119-133; Mann, Margaret Macdonald 2005, pp. 73-155; Morin-Pelletier, Mélanie: Lire entre les Lignes. Témoignages d’Infirmières des hôpitaux militaires canadiens-français postés en France, 1915-1919, in: Bulletin d’histoire politique 17/2 (2009), pp. 57-74; Stuart, Meryn: Social Sisters. A Feminist Analysis of the Discourses of Canadian Military Nurse Helen Fowlds, 1915-18, in: Elliott, Jayne / Stuart, Meryn / Toman, Cynthia (eds.): Place and Practice in Canadian Nursing History, Vancouver 2008, pp. 25-39; Toman, Cynthia: A Loyal Body of Empire Citizens. Military Nurses and Identity at Lemnos and Salonika, 1915-17, in Elliott / Stuart / Toman, Place 2008, pp. 8-24; Bishop Stirling, Terry: Such Sights One Will Never Forget. Newfoundland Women and Overseas Nursing in the First World War, in: Glassford / Shaw, Sisterhood 2012, pp. 126-147.

- ↑ Quiney, Linda J.: Assistant Angels. Canadian Voluntary Aid Detachment Nurses in the Great War, in: Canadian Bulletin of Medical History 15/1 (1998), pp. 189-206; Quiney, Linda J.: Sharing the Halo. Social and Professional Tensions in the Work of World War One Canadian Volunteer Nurses, in: Journal of the Canadian Historical Association 9/1 (1998), pp. 105-124; Mann, Margaret Macdonald 2005, pp. 87ff.

- ↑ Basmajian, Silva (producer): And We Knew How to Dance. Women in WWI, issued by National Film Board of Canada 1993, online: [1] (retrieved: 23 June 2014).

- ↑ Morton, Fight 2004, pp. 64-86, 118; Glassford, Greatest Mother 2008, pp. 219-232; Glassford, Sarah: Volunteering in the First and Second World War, issued by Wartime Canada, online: [2] (retrieved: 15 April 2015); Pickles, Katie: Female Imperialism and National Identity. Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire, Manchester 2002, pp. 42-48; Quiney, Linda J.: Bravely and Loyally They Answered the Call. St John Ambulance, the Red Cross, and the Patriotic Service of Canadian Women during the Great War, in: History of Intellectual Culture, 5/1 (2005), pp. 1-19; Rutherdale, Hometown 2004, pp. 192-223;

- ↑ Cuthbert Brandt et al., Canadian Women 2011, p. 267.

- ↑ Morton, Fight 2004, p. 240; Glassford, Greatest Mother 2008, pp. 226ff.

- ↑ Cuthbert Brandt et al., Canadian Women 2011, p. 269. The provincial battles are covered in Cleverdon, Woman Suffrage 1974, pp. 19-40. On the election of McKinney and MacAdams see Marshall, Debbie: Give Your Other Vote to the Sister. A Woman’s Journey into the Great War, Calgary 2007.

- ↑ Cleverdon, Woman Suffrage 1974, pp. 127, 134; Sangster, Mobilizing 2005, pp. 159-163.

- ↑ Ramkhalawansingh, Women 1974, pp. 285ff; Sangster, Mobilizing 2005, pp. 176f.

- ↑ Cuthbert Brandt et al., Canadian Women 2011, pp. 286, 384; Ramkhalawansingh 1974, p. 287.

- ↑ Duley, Margot: The Unquiet Knitters of Newfoundland. From Mothers of the Regiment to Mothers of the Nation, in: Glassford / Shaw, Sisterhood 2012, pp. 68ff; Cleverdon, Woman Suffrage 1974, pp. 156-264; Strong-Boag, Veronica: The New Day Recalled. Lives of Girls and Women in English Canada, 1919-1939, Toronto 1988.

Selected Bibliography

- Allard, Geneviève: Des anges blancs sur le front. L’expérience de guerre des infirmières militaires canadiennes pendant la Première Guerre mondiale, in: Bulletin d’histoire politique 8/2-3, 2000, pp. 119-133.

- Brookfield, Tarah: Divided by the ballot box. The Montreal Council of Women and the 1917 election, in: Canadian Historical Review 89/4, 2008, pp. 473-501.

- Butlin, Susan: Women making shells. Marking women's presence in munitions work 1914-1918. The art of Frances Loring, Florence Wyle, Mabel May, and Dorothy Stevens, in: Canadian Military History 5/1, 1996, pp. 41-48.

- Cook, Tim: Wet canteens and worrying mothers. Alcohol, soldiers, and temperance groups in the Great War, in: Histoire Sociale/Social History 35/70, 2002, pp. 311-330.

- Glassford, Sarah: The greatest mother in the world. Carework and the discourse of mothering in the Canadian Red Cross Society during the First World War, in: Journal of the Association for Research on Mothering 10/1, 2008, pp. 219-232.

- Mann, Susan: Margaret Macdonald. Imperial daughter, Montreal 2005: McGill-Queen's University Press.

- Mann, Susan (ed.): The war diary of Clare Gass, 1915-1918, Montreal 2000: McGill-Queen's University Press.

- Marshall, Debbie: Give your other vote to the sister. A woman's journey into the Great War, Calgary 2007: University of Calgary Press.

- McKenzie, Andrea: Women at war. L. M. Montgomery, the Great War, and Canadian cultural memory, in: Mitchell, Jean (ed.): Storm and dissonance. L. M. Montgomery and conflict, Newcastle 2008: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 83-105.

- Morin-Pelletier, Mélanie: Des oiseaux bleus chez les Poilus. Les infirmières des hôpitaux militaires canadiens-français postés en France, 1915-1919, in: Bulletin d’histoire politique 17/2, 2009, pp. 57-74.

- Morton, Desmond: Fight or pay. Soldiers' families in the Great War, Vancouver 2004: UBC Press.

- Quiney, Linda J.: Bravely and loyally they answered the call. St John Ambulance, the Red Cross, and the Patriotic Service of Canadian Women during the Great War, in: History of Intellectual Culture 5/1, 2005, pp. 1-19.

- Quiney, Linda J.: Assistant angels. Canadian Voluntary Aid Detachment nurses in the Great War, in: Canadian Bulletin of Medical History 15/1, 1998, pp. 189-206.

- Ramkhalawansingh, Ceta: Women during the Great War, in: Acton, Janice / Goldsmith, Penny / Shepard, Bonnie (eds.): Women at work. Ontario, 1850-1930, Toronto 1974: Canadian Women's Educational Press, pp. 261-307.

- Roberts, Barbara: Why do women do nothing to end the war? Canadian feminist-pacifists and the Great War, Ottawa 1985: Canadian Research Institute for the Advancement of Women.

- Rutherdale, Robert Allen: Hometown horizons. Local responses to Canada's Great War, Vancouver 2004: UBC Press.

- Sangster, Joan: Mobilizing women for war, in: MacKenzie, David Clark (ed.): Canada and the First World War. Essays in honour of Robert Craig Brown, Toronto; Buffalo 2005: University of Toronto Press, pp. 157-193.

- Shaw, Amy J. / Glassford, Sarah (eds.): A sisterhood of suffering and service. Women and girls of Canada and Newfoundland during the First World War, Vancouver; Toronto 2012: UBC Press.

- Sheehan, Nancy: The IODE, the Schools and World War I, in: History of Education Review 13/1, 1984, pp. 29-44.

- Toman, Cynthia: A loyal body of Empire citizens. Military nurses and identity at Lemnos and Salonika, 1915-17, in: Stuart, Meryn Elisabeth / Elliott, Jayne / Toman, Cynthia (eds.): Place and practice in Canadian nursing history, Vancouver 2008: UBC Press, pp. 8-24.