Introduction↑

Australia’s response to the Great War both shaped and was shaped by religion. In a culture that tended to keep religion out of the public eye, religious allegiances surfaced in war-related issues, both at home and in the theatres of war. While overtly secular, Australian politics and society still operated within a consensus of a Christian world-view, and the interplay of faith and society during the war revealed that religion was still a significant force, which has often been under-estimated in Australian history.

The Churches and Wartime Australia↑

About 98 percent of the Australian population in 1911 claimed to be Christian, with four denominations, Anglican (about 40 percent), Roman Catholic (about 23 percent), Presbyterian (nearly 13 percent) and Methodist (over 12 percent), making up the majority. Less than one-quarter of 1 percent claimed no religion, and non-Christian religions were present only in token numbers, the most visible of which was Judaism. However, many Australians were nominal Christians, and active church attendance was probably between 20 to 25 percent of the population, although the churches still retained considerable influence in public life.[1]

All the major denominations offered public support for the war. Both Protestant and Catholic churches emphasised their loyalty to the Australian imperial cause, for as one chaplain said, “The cause of Empire is the cause of God.”[2] While some historians have faulted the churches for their uncritical support for the war, the “Just War” theology of the time made it likely that most clergy would support the war effort, though some cast it as a necessary evil. Preachers enthusiastically supported Britain’s cause in nobly defending liberty and justice for the weak, in this case personified by Belgium. German Lutheranism’s liberal theology and support for Prussian military authoritarianism, on the other hand, was castigated.[3] Some churches, particularly those of an evangelical outlook, also saw the war as divine punishment for national wickedness, such as secularism, Sabbath-breaking, gambling, and drinking, and as God’s call to national and imperial righteousness. There was a widespread expectation among church leaders of a religious revival because of the war.[4] Churches also showed support for the war through national days of prayer for victory for the Empire, and for national repentance and renewal – preconditions in the minds of many to God granting victory to the Allies.

There were differences in levels of support for the war. Anglicans were perhaps the most uniformly supportive, while many Catholics had reservations over the war’s potential to harm Irish Catholic working-class interests. Smaller dissenter denominations, while broadly supportive of the imperial cause, feared that the vices of a military culture would corrupt their young men, and were reluctant to endorse the violence that necessarily accompanies war.

The churches accepted the responsibility of bringing news of the death of soldiers to their families, intending to show empathy and pastoral care. Unfortunately, it had the unintended consequence of making clergy home visitations feared because of the very real possibility that they brought fateful news.

In the anti-German xenophobia whipped up particularly by the federal government under Prime Minister Billy Hughes (1862-1952), the Anglo churches acquiesced to the persecution of Lutheran churches, whose predominantly German congregations were subjected to harassment and internment. Catholic attempts to defend German missionaries merely led to accusations of Catholic disloyalty.[5]

Evangelical churches led the campaign for Temperance reform, gaining political leverage after alcohol-fuelled public disturbances from servicemen. Several states introduced early closing times for public bars, but this merely created a new Australian practice of binge drinking before 6pm. It had virtually no impact on the overall level of alcohol consumption.[6]

The horrific casualties of the war had an impact on Christian theology, leading to new explorations of the doctrine of conditional immortality in the Presbyterian tradition and increased emphasis on prayers for the dead by Anglo-Catholics. Evangelicals found the war forced them to reconsider various eschatological interpretations, as some had labelled the war as being the biblical Armageddon.[7] All churches faced questions of theodicy, asking where God was in the face of the horrors of the war.

The Churches and War Welfare↑

Most churches turned their usual fund-raising activities, such as special offerings, fairs, markets, and concerts into events to benefit various war charities, such as the Red Cross, and the Comforts Fund. Churches ran recreation halls in Australian training camps, providing refreshments, reading matter, games and letter-writing materials to soldiers. The Church of England Men’s Society created a “war department” to support the work of Anglican chaplains in the military camps and hospitals.

Para-church organisations, most notably the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA), provided similar halls in training camps, but went further in creating a network of halls across Egypt, England and France to provide wholesome leisure activities for soldiers, and canteens serving hot drinks to soldiers at the front. The Salvation Army also had a highly visible presence near the fighting fronts with its halls and stalls providing similar services. Because most of the churches supported existing war charities, their contribution to the practical support for the soldiers often went unnoticed. The YMCA and Salvation Army were probably the only two Christian organisations whose reputation was enhanced during the war, precisely because of their visible “applied Christianity”.[8]

Recruiting and Conscription↑

Many churches actively encouraged men to join the all-volunteer Australian Imperial Force (AIF), with appeals in sermons, and denominational newspapers promoting the cause. Important clergymen took the lead in promoting recruiting. For example, the heads of the Anglican, Presbyterian, Methodist and Congregational churches of Sydney issued a joint recruiting appeal in December 1916, while combined church choirs sang at after-church recruiting meetings, and memorial services appealed for more soldiers. Prominent Anglican and Catholic Church leaders headed up official recruiting organisations in various states.

As voluntary enlistment waned, two referenda for conscription were conducted (October 1916 and December 1917) in increasingly divisive terms, which drew religious factions into the debate. The militant rhetoric of Catholic Archbishop of Melbourne, Daniel Mannix (1864-1963), against conscription inflamed sectarian tensions and, along with suspicions of anti-English Irish nationalism, made the largely Irish-Australian Catholics an easy target for Protestant Imperialists. They were accused of undermining the war effort and failing to enlist in proportion to the population, which an uncritical glance at recruitment statistics seemed to confirm, though a closer analysis of the data suggests that enlistments roughly followed the denominational proportions in the census data, especially given the many anomalies in recording the religious affiliation of recruits.[9]

The failure of both referenda exacerbated deep divisions in religion, not to mention politics and society. Despite accusations of disloyalty, probably a majority of Catholics voted for conscription. Presbyterian leaders claimed political neutrality but effectively promoted conscription, while Methodists, Congregationalists and other small denominations tended to argue against compulsion on the grounds of freedom of conscience.[10] While expressing scepticism towards the war, evangelical groups were often the most generous in financial support for war causes and in the “giving of their sons to the god of battle.”[11]

A lasting legacy of the conscription debates was a society fractured along religious lines, as suspicions between empire loyalists, especially among Anglicans, on the one hand, and Catholics and some smaller Protestant groups on the other made the already profound sectarianism in Australia increasingly toxic. The legacy lasted for years after the war, influencing day-to-day life such as choice of marriage partner or employment. However, while popular opinion allocated particular views on conscription to particular religions, “the lines of conflict cannot be neatly drawn along religious lines,” as support or opposition to conscription was not easily determined by religion, class or any other single factor.[12]

Religious Opposition to the War↑

While the majority of churches supported the war, there were pockets of opposition. Some Evangelicals were at best tepid in their support, seeing war as “contrary to Christian beliefs and principles.”[13] Several of the smaller denominations leaned towards conscientious objection, encouraging their men to serve as stretcher-bearers rather than in combat roles. The government had instituted compulsory military training in anticipation of the introduction of conscription, but some groups, like the Seventh-day Adventists, struck a deal with the authorities as self-proclaimed “conscientious co-operators,” willing to serve the nation in any non-combat role.

Active opposition to enlisting on religious and moral grounds came from family members and from individual Presbyterian, Methodist, Baptist or Church of Christ church members. Only the Quakers took a formal stand against participation in the war, though enlistment papers show thirty-two Quakers who volunteered.[14]

A handful of brave individual church leaders opposed to the war found themselves in unlikely alliances with other pacifists from radical left-wing and women’s movements, but faced opposition from their congregations and church hierarchies that saw some resign from their parishes and others attacked by their own parishioners.[15]

Commemoration↑

Commemoration services were organised for the first anniversary of the landings of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) at Gallipoli. On 25 April 1916, various interest groups came together to remember Anzac Day, as it was termed. Events in Brisbane were initiated by Anglican Canon John Garland (1864-1939), whose work inspired memorial services in other states of Australia. Churches were intimately involved in Anzac Day remembrances from the start, and religious elements were blended with civic ceremonies in the memorial activities.

Over time, the direct connection with religion posed some problems, firstly for Catholic servicemen, who were forbidden from attending interdenominational services, and then for secular Australians who felt uncomfortable with religious elements. While Anzac Day and the associated Anzac legend assumed the status of a civic religion in Australia, nevertheless, many religious elements coexisted. Religiously-infused statements make up about a third of the inscriptions on Australian war graves, varying from clichéd to deeply personal expressions, and religious sentiment played an important role in family commemoration of the war dead.[16] Places and rituals associated with Anzac, such as the Australian War Memorial and Returned Services Leagues (RSL) clubs with their daily recital of the Ode of Remembrance, and state and local monuments, memorial halls and plaques, acted as national spiritual focal points.[17] Clubs such as the RSL offered safe social havens for returned servicemen in ways that the fractured churches did not.[18]

Religion and the AIF↑

Chaplains↑

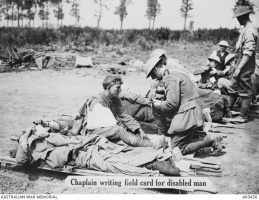

Chaplains were selected by their denominations and appointed to the AIF on the basis of four per brigade, usually comprising two Anglicans, one Roman Catholic and one either Presbyterian or Methodist. Occasionally, the second Anglican was replaced by a chaplain from the smaller denominations, collectively known in the army as Other Protestant Denominations (OPD). In theory, chaplains served their co-religionists across the brigade, but in practice each became associated with one of the four brigade battalions. No training or briefing was given to chaplains, most of whom had no military experience, instead learning their duties on the job. Their key responsibilities were running services for the compulsory Sunday Church Parades and organising additional voluntary religious activities. In action, chaplains assisted the regimental doctor at the aid post, visited the wounded and buried the dead. Chaplains were often expected to help maintain morale, taking responsibility for organising battalion recreation, sports and concerts, and supplying reading material. They also assumed other duties such as censoring the mail, organising canteens, running hot drinks to men in the trenches, and chairing the Officers’ Mess.

While the change from the gentler ways of a peacetime parish to wartime chaplain in charge of 1,000 mostly non-religious men was often confronting, most chaplains made the transition successfully. Soldiers valued chaplains who shared their hardships, served all classes and creeds without distinction, and who looked out for the welfare of the men. Some chaplains failed to adapt, ignoring the men, offending through excessive officiousness or through sectarian discrimination. However, most chaplains won the respect of the men they served, through attention to the men’s needs, which often made a difference to morale. Chaplains also helped maintain faith in the cause, supplying religious and moral justification for the war, and aided discipline by encouraging the men to avoid drunkenness, theft and venereal disease. At the front, many chaplains distinguished themselves by visiting soldiers in the trenches, rescuing the wounded during battles and conducting funerals under fire. Outstanding chaplains such as James Gault (1865-1938), Walter Dexter (1873-1950), Andrew Gillison (1868-1915), Michael Bergin (1879-1917) and William McKenzie (1869-1947) were profoundly influential and at times almost revered, becoming the subjects of legendary exaggerations of their work.

Chaplains found their religious preconceptions challenged by soldier behaviour. Many men disregarded Christian standards of behaviour on alcohol, profanity, sex and gambling, yet exemplified the greatest Christian virtue of self-sacrifice, which persuaded a number of chaplains to become less obsessed with superficial "sins", and conclude that true religion existed at a deeper level. The experience of war led some chaplains to lose faith in religion, while others lost faith in their denominations while remaining Christians. A number of chaplains found themselves unwilling or unable to resume civilian pastoral work after the strains of the war.

Soldier Religion↑

The Australian soldier characteristically gave the impression of a disdain for religion, which many observers took at face value. But, as one chaplain wrote, beneath this show of indifference there often existed a “fine religious sense and faith in the Divine Power,” a sentiment echoed by a number of other informed observers.[19]

Soldier diaries indicate that a surprising number of men engaged positively with organised religion. While the surviving evidence makes it difficult to be precise, a study of Anzac diaries and letters indicates that it was as high as 20 percent or more. Soldier diaries were twice as likely to express appreciation over dislike for compulsory church services, and recorded attendance at voluntary services, or participation in soldier-initiated devotional activities such as Bible study or prayer groups.[20] For many, it was their first extended experience of interdenominationalism, and it often reduced or removed their prejudices to find shared faith among a group of heterogeneous denominational affiliations. Faith in God provided a substantial minority with a moral justification for fighting and with a framework to contextualise death, defeat and wounds.[21]

However, despite the hope that the perils of battle would inspire interest in religion, the conflict did relatively little to spread religious faith. A good many lost confidence in any religion that supported the bloodbath of the war, while others accepted religion to help them cope. Most Christians kept their faith under the trials of war, while the non-religious majority of soldiers developed a fatalism rather than a faith as their spiritual comfort.

Historiography↑

Australian historiography has characteristically minimised the role of religion, and the Great War is no exception. The official history of the war rarely delves into religion, one writer arguing that Australian soldiers accepted chaplains as “an example of that Australian habit of paying lip-service to religion, of pretending that religion mattered here.”[22] C.E.W. Bean (1879-1968), the principal author of the volumes, and himself a clergyman’s son, rarely mentioned the chaplains, although he had intended a separate volume on them, which was never realised under pressures of time and finances.[23] Bill Gammage’s seminal study of the Anzacs, The Broken Years, (1974) argued that “the average Australian soldier was not religious,” accurately adding that in this he was probably little different from the soldiers of other national armies.[24] Several historians have explored the issue of the Anzacs and religion, and some have challenged his findings. Michael McKernan’s 1980 pioneering studies of Australian religion and the war highlighted the role of the churches but did little to change Gammage’s conclusions. More recently, studies of Evangelicals and the war and AIF headstone inscriptions have concluded that “significant numbers of them appear to have been more interested in religion than has often been thought.”[25] Michael Gladwin’s Captains of the Soul (2013), a belated history of Australian army chaplains sponsored by the army, found that chaplains, far from Gammage’s pessimistic view of them being distrusted by the soldiers, were frequently held in high regard, a view supported by a biography of legendary AIF chaplain William McKenzie.[26] A study of AIF soldier diaries and letters is the first in-depth examination of soldier attitudes to religion and spirituality, also concluding that these have been seriously underestimated in both academic literature and popular imagination.[27]

Debate over the origins of Anzac Day has seen some historians proposing largely secular origins while others have pointed to the religious figures who first brought the day to life. Ken Inglis’ ground-breaking study Sacred Places (2005) situated the Anzac legacy in a national secular context with little reference to religion, though to be fair, Inglis was the first to highlight a religious connection to Anzac Day in the 1960s. Graham Seal has also discussed the Anzac dawn service without examining its religious origins.[28] This has been countered by John A. Moses and his detailed study of the religious origins of Anzac Day, especially through the work of Canon David Garland.[29] A compilation, edited by Tom Frame, brings together a variety of eminent scholars who discuss the origins and nature of Anzac Day, both religious and secular, while an entire issue of a journal discusses religious aspects of Australia’s war.[30]

Conclusion↑

Though difficult to find in much Australian Great War historiography, religion was an important factor in the war. The support of most churches gave moral justification for the conflict, impetus to recruiting, and remained a significant source of charitable aid. While the bulk of the soldiers of the AIF were not overtly religious, they seemed to welcome the ministry of chaplains and Christian service organisations, and a significant minority were active Christians. The war fostered an ecumenical spirit among many soldiers, but the divisive referendum campaigns deepened sectarianism in the churches at home. Returning soldiers found spiritual refuge in service clubs rather than churches, and despite the Christian origins and influences on Anzac Day, the legacy of Anzac in Australia is now both deeply spiritual and secular.

Daniel Reynaud, Avondale College of Higher Education

Section Editor: Peter Stanley

Notes

- ↑ McKernan, Michael: Australian Churches at War: Attitudes and Activities of the Major Churches 1914-1918, Sydney & Canberra 1980, pp. 6-10.

- ↑ Cuttriss, G. P.: ‘Over the Top’ with the Third Australian Division, London 1918, p. 120.

- ↑ McKernan, Australian Churches 1980, p. 178; Moses, John A.: ‘The First World War as Holy War in German and Australian Perspective,’ in Colloquium, 26/1 (1995), p. 48; Piggin, Stuart: Spirit, Word and World: Evangelical Christianity in Australia (Revised Ed.), Brunswick East 2012, p. 83.

- ↑ Thompson, Roger C.: Religion in Australia: A History, Melbourne 1994, p. 57.

- ↑ Connor, John/Stanley, Peter/Yule, Peter: The War At Home, Oxford 2015, p. 207.

- ↑ Carey, Hilary M.: ‘An Historical Outline of Religion in Australia,’ in Jupp, James (ed.), The Encyclopedia of Religion in Australia, Melbourne 2009, p. 18.

- ↑ Connor/Stanley/Yule, The War At Home 2015, p. 189.

- ↑ Reynaud, Daniel: Anzac Spirituality: The First AIF Soldiers Speak, North Melbourne 2018, p. 262.

- ↑ Reynaud, Anzac Spirituality 2018, pp. 19-21; Bou, Jean/Dennis, Peter/Dalgleish, Paul: The Australian Imperial Force, Oxford 2016, pp. 90-93.

- ↑ Thompson, Religion in Australia 1994, pp. 60-62.

- ↑ Linder, Robert D.: The Long Tragedy: Australian Evangelical Christians and the Great War, 1914-1918, Adelaide 2000, pp. 75-76.

- ↑ Carey, Hilary M.: ‘Religion and Society,’ in Schreuder, Deryck M./Ward, Stuart (eds.) Australia’s Empire, Oxford 2008, p. 206.

- ↑ Treloar, Geoffrey R.: The Disruption of Evangelicalism: The Age of Torrey, Mott, McPherson and Hammond, Downers Grove 2017, p. 125.

- ↑ Reynaud, Anzac Spirituality 2018, pp. 132-134, 18.

- ↑ Connor/Stanley/Yule, The War At Home 2015, pp. 183, 189.

- ↑ Bale, Colin: A Crowd of Witnesses: Epitaphs on First World War Australian War Graves, Haberfield 2015, pp. 164, 240; Lake, Meredith: The Bible in Australia: A Cultural History, Sydney 2018, pp. 266-267.

- ↑ See in particular Inglis, Ken: Sacred Places: War Memorials in the Australian Landscape, Carlton 2005.

- ↑ Thompson, Religion in Australia 1994, pp. 98-90.

- ↑ Beveridge, Sidney quoted in Reynaud, Anzac Spirituality 2018, p. 297, see also pp. 251-255, 300-305.

- ↑ Reynaud, Anzac Spirituality 2018, pp. 298, 35, 51, 66-124.

- ↑ Reynaud, Daniel/Fernandez, Jane: ‘“To Thrash the Offending Adam out of Them”: The theology of violence in the writings of Great War Anzacs,’ in Hartney, Christopher: Secularisation: New Historical Perspectives, Cambridge 2014, pp 134-150.

- ↑ Gullett, H. C.: The AIF in Sinai and Palestine, Sydney 1944, p. 551.

- ↑ McKernan, Michael: ‘Foreword,’ in Reynaud, Daniel: The Man the Anzacs Revered: William ‘Fighting Mac’ McKenzie, Anzac Chaplain, Warburton 2015, p. v.

- ↑ Gammage, Bill: The Broken Years: Australian Soldiers in the Great War, Melbourne 1974, pp xiv-xv.

- ↑ McKernan, Australian Churches 1980; McKernan, Michael: Padre: Australian Chaplains in Gallipoli and France, Sydney 1986; Linder: The Long Tragedy 2000; Bale, Colin: ‘In God We Trust: the impact of the Great War on Religious Belief in Australia,’ in Bolt, Peter G./Thompson, Mark D. (eds): Donald Robinson: Selected Works; Appreciation, Camperdown 2008, p. 307.

- ↑ Gladwin, Michael: Captains of the Soul: A history of Australian Army chaplains, Sydney, 2013; Reynaud: The Man the Anzacs Revered 2015.

- ↑ Reynaud, Anzac Spirituality 2018.

- ↑ Inglis, Ken: Sacred Places: War Memorials in the Australian Landscape, Carlton 2005; Seal, Graham: ‘... and in the morning ...’: adapting and adopting the dawn service, Journal of Australian Studies, 35/1 (2011), 49-63.

- ↑ Moses, John A./Davis, George F.: Anzac Day Origins: Canon DJ Garland and Trans-Tasman Commemoration, Canberra 2013.

- ↑ Frame, Tom (ed.): Anzac Day Then and Now, Sydney 2016; St Mark’s Review, 231/1, 2015.

Selected Bibliography

- Bale, Colin: A crowd of witnesses. Epitaphs on First World War Australian war graves, Haberfield 2015: Longueville Media.

- Frame, Tom (ed.): Anzac Day then and now, Sydney 2016: University of New South Wales Press.

- Gladwin, Michael: Captains of the soul. A history of Australian Army chaplains, Newport 2013: Big Sky Publishing.

- Inglis, Kenneth Stanley / Brazier, Jan: Sacred places. War memorials in the Australian landscape, Carlton 1998: Melbourne University Press.

- Lake, Meredith: The Bible in Australia. A cultural history, Chicago 2018: University of New South Wales Press.

- Linder, Robert Dean: The long tragedy. Australian evangelical Christians and the Great War, 1914-1918, Adelaide 2000: Openbook Publishers.

- McKernan, Michael: Padre. Australian chaplains in Gallipoli and France, Sydney; London; Boston 1986: Allen & Unwin.

- McKernan, Michael: Australian churches at war. Attitudes and activities of the major churches 1914-1918, Sydney; Canberra 1980: Catholic Theological Faculty; Australian War Memorial.

- Moses, John A.: The struggle for Anzac Day 1916-1930 and the role of the Brisbane Anzac Day Commemoration Committee, in: Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society 88/1, 2002, pp. 54-74.

- Moses, John A. / Davis, George F.: Anzac Day origins. Canon DJ Garland and trans-Tasman commemoration, Canberra 2013: Barton Books.

- Reynaud, Daniel: Revisiting the secular Anzac. The Anzacs and religion, in: Lucas: An Evangelical History Review 2/9, 2015, pp. 73-101.

- Reynaud, Daniel: Anzac spirituality. The first AIF soldiers speak, Melbourne 2018: Australian Scholarly Publishing.

- Reynaud, Daniel / Fernandez, Jane: ‘To thrash the offending Adam out of them'. The theology of violence in the writings of Great War Anzacs, in: Hartney, Christopher (ed.): Secularisation. New historical perspectives, Newcastle upon Tyne 2014: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 134-150.

- St Mark's Review, volume 231, 2015