Introduction↑

Existing research on pre-war military planning in Canada concentrates on interactions between Canadian Ministers of Militia with British army officials, focusing on the imperial relationship and civil-military interactions. The Canadian Militia, with its longstanding colonial dependence on British garrisons and commanding officers, was slowly moving toward greater Canadian political and military autonomy and yet still retained a clear sense of duty to the Empire. Canadian military planning was also complicated by two founding cultures, English and French, with each holding conflicting conceptions of imperial duty. Two Ministers of Militia in the pre-war period, Sir Frederick Borden (1847-1917), from 1896 to 1911 and Sir Sam Hughes (1853-1921), 1911 to 1916, figured prominently in this period of gradually increasing nationalism. Canadian military planning was largely under British command and control during the South African War of 1899-1902 but over the next few years came to be increasingly directed by Canadian authorities.

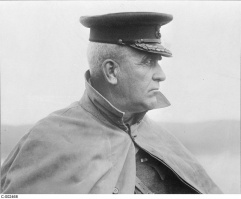

Frederick Borden, Canada’s Minister of Militia, 1896↑

Election of 1896↑

The Canadian general election of 1896 was a turning point for the Canadian Militia. The economic depression of the early 1890s finally lifted, attracting new immigrants from Britain and eastern Europe. The election of a new Liberal government led by an energetic prime minister, Wilfrid Laurier (1841-1919), corresponded with an renewed sense of optimism for Canada’s future. Business began to grow, railways expanded, and, more importantly for the military, Frederick Borden was named Minister of Militia and Defence. Borden commenced an active program of military reform; he increased the authorized strength of Canada’s voluntary Militia forces from about 10,000 to over 35,000. To help ensure promotion based on merit to reduce the impact of patronage appointments, he limited the tenure of command of local units to five years. The leading publication in military affairs, the Canadian Military Gazette, expressed its approval of Borden’s progressive, business-like approach: “It freshens and braces the love of soldiering which is too often allowed to flag and eventually die out altogether.”[1]

Militia Foundations↑

Military planning at the turn of the century involved a combination of British imperial control and direction from Canada’s elected government, as established at Confederation by the British North America Act, 1867. The Dominion Militia Act of 1868 granted the Canadian federal government power to organize the defense of the new nation by creating the Canadian Militia under British command. The force would consist primarily of part-time volunteers: the Active Militia with 40,000 soldiers who were to train from eight to sixteen days annually, as well as a small full-time Permanent Force to act as instructors.

Among the formative influences upon the 1868 act had been the exceedingly tense Anglo-American relations during the American Civil War and the Fenian Raids that fell upon British North America in 1866. The Irish-American Fenian Brotherhood was an underground movement that formed in the United States with the intent of securing Irish independence from Britain. By 1865, this organisation had amassed substantial funding and its membership included some 10,000 battle-hardened Irish-American Civil War veterans who believed the conquest of Canada to present no great obstacle. The captive British colonies would then be exchanged for a free Ireland.[2] Although the Fenian raids of 1866 accomplished nothing for Ireland, they had a decisive influence on Canada by confirming for British North Americans that they lived in a portion of the Empire that was inherently vulnerable to attack from the United States. For that reason, the defense of Canadian territory against American aggression would remain a key focus of Canadian defense planning into the early 20th century. Before Borden’s appointment as Militia minister, however, few Canadians actually concerned themselves with military affairs except during periods of emergency, such as the Red River Rebellion of 1869 and the Northwest Rebellion of 1885, both consisting of brief Métis uprising led by Louis Riel (1844-1885). Outside of these short periods of bellicosity and martial enthusiasm, the Canadian Militia was languishing in the early 1890s from lack of interest and the frequent cancellation of its annual training. Canadians relied on protection by the Royal Navy and their belief in raising a volunteer citizen army in times of emergency to avoid raising a strong standing army.

Prior to the Great War, the central focus for Canadian military development was to create an army that could help Britain defend Canada’s borders in the event of war and preserve law and order while making only limited peacetime demands in terms of both manpower and taxation. This defensive purpose represented the Dominion’s only real military obligation as part of the British Empire. The intent was to create a militia that could be expanded in time of war for the defense of Canadian territory itself. The Toronto Globe typified Canadian thinking when it declared, “Canadians can dispense with a standing army because they possess the best possible constituents for a defensive force in themselves.”[3] Based on this faith in a voluntary force, many believed Canada did not have to prepare for its defence in any serious way. Few Canadians saw any pressing need for Canadians to serve overseas; thus, a militia composed of part-time citizen soldiers seemed best suited to the task.

At the beginning of the 20th century, however, the amateur approach to military affairs was becoming obsolete. While British officers stationed in Canada struggled alongside a socially isolated cadre of Canadian Permanent Force officers to establish the foundations of military professionalism, they faced the indifference of most Canadians to their efforts. When Edward T.H. Hutton (1848-1923) arrived in Canada as General Officer Commanding (GOC) with plans to create a “National Army”, his energetic approach helped overcome this indifference, lifting spirits and renewing Canadian martial interests at roughly the same moment that the British Empire was facing a new crisis in South Africa.

The War in South Africa, 1899 -1902↑

Serving the Empire↑

At the 1897 Imperial Conference, Prime Minister Laurier supported growing military ties between the British Dominions and the Empire, including steps toward ensuring uniformity of equipment, drill, and weaponry. Partially for that reason, imperial expectations were high in calling for colonial support shortly after Britain declared war against the Boer Republics in 1899. Laurier, however, immediately faced stiff resistance by the French-speaking population of Quebec who feared that a precedent was being set for future Canadian involvement in British wars. The fervent conflict of views was fought out in the press and among Laurier’s own cabinet ministers.

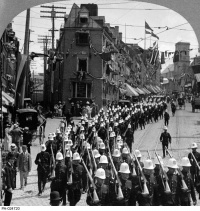

As GOC, General Hutton pressured Prime Minister Laurier and his minister of Militia to immediately recruit a force of volunteers to set sail for South Africa. Supported by the Queen’s representative in Canada, Governor General Gilbert John Elliot-Murray-Kynynmound, 4th Earl of Minto (1845-1914), as well as strong imperialist sentiment in the heavily-populated province of Ontario, Hutton planned for a volunteer force. Many employers encouraged enlistment and patriotic organizations offered their support. Enthusiastic English-Canadian crowds gathered in Toronto to cheer on the Queen’s Own Rifles as they commenced training.[4] Carried away by popular opinion, an editorial in the Canadian Military Gazette prematurely announced the formation of an eight-company militia battalion that was being formed for overseas service. A statement by Prime Minister Laurier the following day dismissed the statement as “pure invention,” having no foundation in fact and “wholly imaginative.”[5] By this point, however, English-speaking imperialists were urging full support for the Empire in its hour of need and Laurier resigned himself to allowing a volunteer force of 1,000 volunteers to be raised in Canada for service in South Africa. The 2nd (Special Service) Battalion of the Royal Canadian Regiment of Infantry under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel William Otter (1843-1929) departed a mere seventeen days after the Cabinet issued an order to organize a force.

The Canadian Contingents↑

Response to the call to arms was so enthusiastic that plans were soon being made for further Canadian volunteer forces. In addition, the Canadian government authorized General Hutton to raise support elements, including two field engineer companies, four army service corps companies, and a medical corps. Eventually Canada sent more than 7,000 troops to South Africa, including a complete regiment of mounted rifles that was personally funded by Canada’s High Commissioner to London, Donald Alexander Smith, Baron Strathcona and Mount Royal, (1820-1914). Not yet a true standing army - for example, there was no general staff, little cohesion between individual units, and lacking supporting corps or services to sustain them - Canadians still took great pride in the volunteers’ accomplishments in South Africa from 1899-1902.

Public support for the military grew as a result of the nation’s strong record during the South African War, with four Canadians winning the Victoria Cross for exceptional bravery in action. In spite of significant growth in national pride throughout English-speaking Canada, tensions between the French- and English-speaking segments of the population intensified. Even before the Boer War relatively fewer French-Canadians were serving in the Canadian Militia than their English-Canadian counterparts, a trend that had been developing since the mid-19th century as British military traditions became more pronounced and English became entrenched as the language of instruction among the Permanent Force. Now faced with the spectacle of the armed might of the British Empire being brought to bear against the non-English Boers of southern Africa, French-Canadians were understandably hesitant to become involved in a force that was becoming increasingly oriented towards an expeditionary force role.

For the country as a whole, however, the war in South Africa represented a turning point. Although Boer fighters had inflicted a series of sharp defeats on British forces in the early stages of the conflict, later successes achieved by Canadian soldiers during subsequent engagements did help turn the tide for Great Britain and bolster greater Canadian faith in a part-time volunteer militia with rifle and horse-riding skills.

Militia Modernization↑

Borden’s Militia Act of 1904↑

The public perception that Canadian troops had performed exceedingly well in the South African War created a groundswell of support for the “citizen army” that Borden now sought to create. He used this momentum to introduce a new Dominion Militia Act in 1904. It formalized improvements already underway during his earlier administration, incorporating new units that were now deemed necessary for a national army, including engineers, signaling corps, intelligence department, reconnaissance force, medical corps, military staff clerks, pay corps, and officers’ training corps. Motivated partly by Borden’s desire to avenge Hutton’s earlier interference in raising troops for South Africa and partly by Borden’s longstanding commitment to win a larger degree of Canadian military autonomy from Great Britain, the 1904 Act also abolished the position of GOC (always held previously by a British officer). Instead, it created a Militia Council and General Staff, thus following the British lead in modernizing the army’s leadership. Modeled on Britain’s Army Council, Canada’s Militia Council was composed of both civilian and military personnel. There were seven members: the minister of Militia and deputy minister, the department chief accountant, plus four military personnel. The chief of general staff, replacing the GOC, was the leading military member, subordinate to the minister, and open for the first time to a senior Canadian officer.

Implementation of Militia Reforms↑

Renewed public support for an expanded Canadian military establishment helped to influence Parliament to increase military budgets. Amid the “Dominion’s military renaissance,”[6] organization improved, new units were created and there was increased emphasis on promotion based on merit rather than the traditional means of exercising political patronage. The Canadian General Staff began to plan for wartime mobilization under the direction of a British officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Willoughby Gwatkin (1859-1925), who served as head of operational planning. In 1906 district staffs received details of Gwatkin’s comprehensive mobilization plans, focusing on a home defense scheme with army reserves of 100,000 and an Active Militia of 40,000 to undergo annual training. In 1908, Brigadier-General William Otter, the first Canadian Chief of General Staff, recommended a staff officer training program for non-permanent Militia officers. The Canadian Militia assumed control of the Halifax and Esquimalt naval bases, completing a process that began with the withdrawal of British garrisons in 1871. Laurier’s government tripled the size of the Permanent Force to 3,000. A national training camp was established at Petawawa near Ottawa.

The momentum continued in 1909 when Borden launched General William Otter’s proposed Militia Staff Course for Canadian reserve officers, an important first step towards institutionalizing formal staff training for Canada’s army. In the same year, the Strathcona Trust, established with a donation of $500,000 by Lord Strathcona, made provisions for financial support of physical and military training in Canadian schools. Its goal was to provide rifle training and military drill to produce future volunteer soldiers for the defense of Canada and the Empire. Marksmanship training flourished and government-funded civilian rifle club membership doubled between 1903 and 1911. Enrolled membership in cadet training increased from 9,000 in 1908 to 44,680 in 1914.[7] Armories opened throughout the cities and towns of Canada, often with exclusive, elaborate facilities for young men of the community. Rifle ranges, gymnasia, bowling alleys, billiard tables, and elaborate dinners were some of the features that led the Militia to play an active role in social life across the country.[8]

A New Focus for Military Planning↑

Canadian - Imperial Relations↑

At the Colonial Conference of 1907, Prime Minister Laurier accepted the principle of imperial military cooperation and agreed that wartime contingencies might someday require the self-governing Dominions to act in mutual support. The sense of commitment became even stronger with the Imperial Conference of 1909. Amid the fears raised by German naval expansion, the Dominions agreed to adopt British standards of army organization, field regulations, training manuals, and patterns of weapons and equipment. Within five years, Canadian militia planning quickly evolved from a focus on defense in North America toward raising an expeditionary force in aid of Great Britain, possibly in a European war.

A Sense of Urgency↑

Rather than contribute directly to the Royal Navy toward further building of dreadnoughts, Laurier introduced legislation on 10 January 1910 to establish a Canadian Navy. He proposed the purchase of eleven warships: five cruisers and six destroyers to be built in Canada. The Conservative leader of the Opposition, Robert Borden, opposed Laurier’s Naval Bill, favoring instead direct contributions to Britain. French-English disputes continued, with the vast majority in the province of Quebec opposing construction of a navy that could be put to use in what their spokesman, Henri Bourassa (1868-1952), described as British imperialist wars. In spite of Laurier’s assertion that “When Great Britain is at war, Canada is at war,”[9] the prime minister realized that with an upcoming election, military planning would have to accommodate divisions within the popular sentiment. With the nation divided over the naval issue into fiercely-opposed English- and French-speaking segments, the Laurier government created the Naval Service of Canada on 4 May 1910. In response to Henri Bourassa’s charges that a precedent was created with the dispatch of land forces for service in the South African War, Laurier asserted that the Dominion retained full control over its navy; only a Parliamentary vote could order ships to serve under the Admiralty’s command. Two cruisers were commissioned: on the Atlantic, HMCS Niobe based at Halifax, and HMCS Rainbow on the Pacific at Esquimalt.

In May 1910, Inspector-General of Imperial Forces, Sir John French (1852-1925), toured Canada at the request of the Laurier government to review and report on the state of the Canadian Militia. The French Report confirmed Borden’s goals by supporting the voluntary system of militia organization but also noting severe deficiencies, including a lack of formal staff training, poor organization, inadequate knowledge among the higher command, and loose enforcement of discipline and qualifications.[10] Parliamentary funds were increased to effectively address the concerns of the French Report and raise professional standards of administration and leadership. In the summer of 1911, the Laurier government instructed General Otter and Director of Mobilization Gwatkin to begin the necessary planning for the dispatch of a large expeditionary force of one infantry division and a cavalry brigade should these be required to assist the British Empire in wartime.

A New Minister: Sam Hughes Takes Command↑

Election of 1911↑

On a platform that won both Ontario’s support for tariff protection of Canadian industries and the support of Quebec owing to a promise to dismantle Laurier’s Naval program, Robert Borden’s Conservatives defeated the Liberals in the 1911 election. The new prime minister appointed Sam Hughes as his Minister of Militia and Defence. Although Hughes had long served as the opposition military critic across the floor from Frederick Borden, they had been friends and shared many military views, especially in their support for voluntary service rather than conscription. Hughes had risen to the rank of colonel in the militia; thus he now attempted to act in a dual military and political role, attending civic and military duties in uniform and often issuing commands as he went.

To garner popular support for military expansion, Hughes organized high-profile militia conferences in 1911 and 1913, summoning officials from the Active Militia, the Permanent Force, and from a variety of civilian organizations, including civilian members of Parliament, newspaper editors, teachers, professors, clergymen, temperance unionists, and the representatives of women’s organizations. The training of a citizen army was discussed in depth, with questions relating to the proficiency of amateur soldiers, the value of marksmanship, a citizen’s obligations in war and peace, and the importance of cadet training in the schools. By 1914, many Canadians believed that military drill and discipline could play a role in educating young men to become good citizens, resulting in further proliferation of cadet corps across the country. Parliamentary support echoed popular opinion: the 1909-10 military budget was $5,921,314. By 1913-14, it had almost doubled to $10,988,162.[11] When British Inspector-General of Overseas Forces, Sir Ian Hamilton (1853-1947), inspected the Canadian Militia in 1913, he noted that many improvements had been made since French’s inspection of 1910. Hamilton stated that training and education had improved, especially among the higher ranks.[12]

On the Eve of the Great War↑

Britain declared war on Germany on 4 August 1914; the Empire now looked to its Dominions for support and Canadians responded with patriotic fervor. Canada, as a dominion, was automatically at war, but Ottawa and Canadians would decide the level of commitment. On 6 August the Canadian cabinet authorized placing on service a force of unspecified size and, two days later, the British Secretary of War, Horatio Herbert Kitchener (1850-1916), responded with hopes for 20,000 to 25,000 men. On 10 August a Canadian order-in-council set the strength of the expeditionary force at 25,000.[13] Based on Gwatkin’s pre-war plans, mobilization should have commenced in an orderly fashion. As it happened, however, Militia Minister Sam Hughes decided to implement his own scheme, starting with new orders that were sent out via late night telegrams to 226 unit commanders across Canada. At Hughes’s direction, these officers were to remit to Ottawa for final approval the names of volunteers willing to go overseas. Hughes was acting on his belief that a citizen army could instantly be called to arms in defense of the Empire much more quickly than the slow-moving mobilization plans that had earlier been established by Gwatkin. In a quest for massive, speedy recruitment, Hughes was also effectively relegating existing Militia regiments to the sidelines, replacing them with composite numbered battalions that were to be formed consecutively as voluntary enlistments poured in.

Ignoring the camp already established at Petawawa, Hughes instead chose the completely undeveloped Valcartier site for assembly, training and deployment. A multitude of organizational difficulties arose and little consideration was given to organization of French-Canadian units. Despite the chaos, the enthusiasm for enlistment was overwhelming throughout English-speaking Canada, particularly among young men who had recently immigrated to Canada from Britain. During September 1914, 36,000 recruits gathered at Valcartier Camp. On 3 October, the First Contingent of the Canadian Expeditionary Force boarded the ships for England. It had weeded out several thousand unfit men but the 31,200 soldiers who went overseas was the single largest movement of Canadian troops up to that point in the Dominion’s history. More than 420,000 other Canadian soldiers and nurses would follow them in the next four years.

Conclusion↑

Few could have foreseen in 1896 that in less than twenty years, Canadian militia volunteers would be formed into an army for service in a European war. By 1918 the transition from a home defense militia to the Canadian Expeditionary Force was complete. Military planning for an Active Militia numbering less than 40,000 in the 1890s had by then expanded to include an army of 619,636 soldiers, including a four-division Canadian Corps that became one of the most effective formations on the Western Front.

James A. Wood, Okanagan College

Section Editor: Tim Cook

Notes

- ↑ “Headquarters News,” in: Canadian Military Gazette 11/17 (September 1896), p. 1.

- ↑ Senior, Hereward: The Last Invasion of Canada: The Fenian Raids, 1866-1870. Toronto 1991, pp. 34-44.

- ↑ Toronto Globe, 26 August 1870, p. 1.

- ↑ Toronto Globe, 14 October 1899, p. 1.

- ↑ “Editorial,” in: Canadian Military Gazette 14/19 (3 October 1899), p. 1; Toronto Globe, 4 October 1899, p. 1.

- ↑ Harris, Stephen: Canadian Brass. Toronto 1988, p. 75.

- ↑ Canadian Annual Review, 1904, Ottawa, p. 466; Report of the Militia Council, 1908, 1911, and 1914, Ottawa, Sessional Papers 1912, no.35, p. 11.

- ↑ “Regimental News and Notes – Infantry and Rifles,” in: Canadian Military Gazette 17/8 (15 April 1902), p. 5.

- ↑ Canada. House of Commons, Debates, 12 January 1910, p. 1735.

- ↑ French, J.: Report by General Sir John French, G.C.B., G.C.V.O., K.C.M.G., Inspector-General of Imperial Forces Upon His Inspection of the Canadian Military Forces, Sessional Papers 1911, Volume 21, no.35a, p. 29.

- ↑ Report of the Militia Council, 1914, Sessional Papers, 1915, no. 35, p. 57.

- ↑ Hamilton, General Sir Ian: Report by the Inspector-General of Overseas Forces on the Military Institutions of Canada, 30 July 1913, p. 25.

- ↑ Nicholson, G.W.L.: The Canadian Expeditionary Force, 1914-1919. Ottawa 1962, p. 18.

Selected Bibliography

- Berger, Carl: The sense of power. Studies in the ideas of Canadian imperialism, 1867-1914, Toronto 1970: University of Toronto Press.

- Brown, Robert Craig: Hughes, Sir Samuel: Dictionary of Canadian biography, volume 15, Toronto 2005: University of Toronto; Université Laval.

- Granatstein, J. L.: Canada's army. Waging war and keeping the peace (2 ed.), Toronto; Buffalo 2011: University of Toronto Press.

- Harris, Stephen J.: Canadian brass. The making of a professional army, 1860-1939, Toronto; London 1988: University of Toronto Press.

- Haycock, Ronald Graham: The controversial Canadian. The public career of Sir Sam Hughes, 1885-1916, Waterloo; Ottawa 1985: Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

- Kohn, Edward P.: This kindred people. Canadian-American relations and the Anglo-Saxon idea, 1895-1903, Montreal 2004: McGill-Queen's University Press.

- Miller, Carman: A knight in politics. A biography of Sir Frederick Borden, Montreal 2010: McGill-Queen's University Press.

- Miller, Carman: Borden, Sir Frederick William: Dictionary of Canadian biography, volume 14, Toronto 1998: University of Toronto; Université Laval.

- Milner, Marc: Canada's navy. The first century, Toronto 1999: University of Toronto Press.

- Morton, Desmond: A military history of Canada (5 ed.), Toronto 2007: McClelland & Stewart.

- Morton, Desmond: The Canadian general. Sir William Otter, Toronto 1974: Hakkert.

- Morton, Desmond: Gwatkin, Sir Willoughby Garnons: Dictionary of Canadian biography, volume 15, Toronto 2005: University of Toronto; Université Laval.

- Morton, Desmond: Ministers and generals. Politics and the Canadian militia, 1868-1904, Toronto 1970: University of Toronto Press.

- Nicholson, Gerald W. L.: Canadian Expeditionary Force, 1914-1919. Official history of the Canadian army in the First World War, Ottawa 1962: R. Duhamel.

- Penlington, Norman: Canada and imperialism, 1896-1899, Toronto 1965: University of Toronto Press.

- Preston, Richard A.: Canada and imperial defense. A study of the origins of the British Commonwealth's defense organization, 1867-1919, Durham 1967: Duke University Press.

- Sarty, Roger: A navy of necessity. Canadian naval forces, 1867-2014, in: Northern Mariner / Le Marin du Nord 24/3/4, 2014, pp. 32-59.

- Stacey, C. P.: Canada and the age of conflict. A history of Canadian external policies, 1867-1921, volume 1, Toronto 2015: University of Toronto Press, online: http://site.ebrary.com/id/11010826 (Retrieved 2015-06-15 18:44:08).

- Wood, James: Militia myths. Ideas of the Canadian citizen soldier, 1896-1921, Vancouver 2010: UBC Press.