Introduction↑

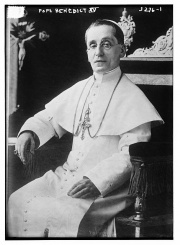

Cardinal Giacomo Della Chiesa (1854-1922) was elected pope, taking the name Benedict XV, a few weeks after the outbreak of the First World War, on 3 September 1914. Although he had been archbishop of Bologna in central Italy for six and a half years prior to his election, his earlier ecclesiastical career had been in papal diplomacy, first in the papal embassy in Madrid, 1883-1887, and then in the Vatican Secretariat of State, where he became the deputy to the Cardinal Secretary in 1901. This experience played a major role in his election: the conclave which elected him was deeply affected by the outbreak of the war. For the cardinals present, it was crucially important that Della Chiesa had no particular links with either of the warring groups but on the other hand possessed a shrewd knowledge of European diplomacy.

Benedict’s first major public statement, the encyclical letter Ad Beatissimi of November 1914, urged the belligerents to come to the negotiating table. This, and his first diplomatic initiative, a call for a Christmas truce, were failures. The British were most opposed to a truce. Though Benedict and his Secretary of State, Cardinal Pietro Gasparri (1852-1934), continued behind-the-scenes efforts to mediate between the warring powers, their peace diplomacy was not successful. Indeed, despite strenuous efforts to avoid an extension of the conflict, in May 1915 Italy intervened in the war on the side of the Entente. In 1916, the Italian government demanded that the embassies of the Central Powers to the Holy See leave Rome. This intervention created difficulties for Vatican diplomacy. Moreover, as a condition of her adherence to the Entente, Italy insisted that Britain, France and Russia should oppose the participation of the Holy See in any subsequent peace conference.

Benedict’s peace diplomacy and humanitarian efforts during the war were motivated by a deep revulsion at the "useless slaughter", as he described it in his Peace Note of 1917. He was outraged by the new methods of waging war: the horrors of trench warfare, the torpedoing of passenger and merchant vessels and the aerial bombardment and shelling of civilian populations. Catholics on both sides invoked “just war” theory to justify their participation in the conflict, but Benedict suggested in his encyclicals that no war, including a total war, could be considered just.

The Vatican’s Humanitarian Relief Programme↑

Benedict’s peace diplomacy was accompanied by his efforts at humanitarian relief. In December 1914, he launched an array of papal relief work which was to some extent comparable with that of the International Red Cross. Its principal focus was prisoners of war, but it also included civilians. By the end of the war, the Vatican “Office for Prisoners” had dealt with a staggering 600,000 items of correspondence, including 170,000 enquiries about missing persons, 40,000 appeals for help in the repatriation of sick and severely wounded prisoners of war and the forwarding of 50,000 letters to and from prisoners and their families. The Vatican arranged for food parcels and other goods to be delivered to prisoner of war camps and for sick and wounded prisoners of war and civilians to convalesce in the hospitals or sanatoria of neutral Switzerland.

Patient diplomacy was needed to get around the obstacles put up by the warring powers, most notably the Italian government, which displayed a particular lack of sympathy and concern for its compatriots taken prisoner by the Austrians.[1] Persuading the powers to allow the passage of papal food relief convoys was even more difficult. The Vatican was involved in feeding famished children in Belgium in 1916, large numbers of people in Lithuania and Montenegro in 1916/1917, and Russian refugees in 1916, as well as food relief in Poland in 1916, and Syria and Lebanon from 1916 to 1923. Benedict was particularly concerned for children and continued to appeal for money for starving children in Central Europe after the war. As Reggie Norton has rightly pointed out, he can thus be regarded as one of the founders of the Save the Children Fund.

The Papal Peace Note, August 1917↑

Benedict made his boldest attempt to stop the war with the Peace Note of August 1917. As early as the autumn of 1916, international groups including Catholic parliamentarians and representatives of Europe’s Socialist parties were pressing for peace and there were rumours of a secret masonic congress to seek a way out of the war. By the summer of 1917, the warring powers were also showing signs of exhaustion. Czarism had collapsed in Russia in February/March, confirming Benedict’s fears about the domestic consequences of war. Austria-Hungary was also approaching exhaustion. Furthermore, there were several mutinies in the French army after the failure of Robert Nivelle (1856-1924)'s spring offensive. Most promising was the passing of a Reichstag resolution in favour of "peace without annexation" in July 1917. Even before the "peace resolution", Benedict had sent Monsignor Eugenio Pacelli (later Pope Pius XII (1876-1958)) as nuncio to Germany to sound out opinion. He was well-received in military and governmental circles and believed that the Germans were willing to negotiate seriously, even on difficult issues like the evacuation and restitution of Belgium.

So, on 1 August, the third anniversary of the outbreak of the war, the Vatican despatched the Peace Note to the heads of the belligerent powers, offering seven key proposals as a practical basis for negotiating peace:

- The re-establishment of the moral force of international law

- Reciprocal disarmament

- International arbitration of disputes

- Freedom of the seas

- Reciprocal renunciation of war reparations

- Evacuation and restoration of occupied territories, and

- The conciliatory negotiation of rival territorial claims.

The response of the belligerents was negative; neither side felt the moment was ripe for a peace initiative. The Germans, despite their courteous reply, felt that they were on a winning streak following the failure of Russian general Alekseĭ Alekseevich Brusilov (1853-1926)’s offensive against them, and following the German refusal, Austria-Hungary could only acquiesce. Most significantly, President Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924) gave it a cool, critical reception which was decisive in ensuring the failure of Benedict’s peace proposals because by now the other Entente powers were increasingly dependent on the American contribution to the war effort.

Benedict was bitterly disappointed by the failure of the Peace Note, and public reactions to it. In France he was denounced as "le pape boche", in largely Protestant Germany he had long been seen as "Der französische Papst", and in Italy some of the more intensely nationalistic elements led by a certain Benito Mussolini (1883-1945) accused him of spreading defeatism.

Conclusion↑

The outcomes of the war for the Holy See were mixed. Vatican peace diplomacy had failed and Benedict’s hopes of a seat at the peace conference had been scuppered. On the other hand, his carefully maintained policy of neutrality had ensured that there was no schism or split in European Catholicism, and Vatican humanitarian relief efforts had significantly enhanced the moral standing of the Holy See. Most striking of all was that the influence of Vatican diplomacy was greatly extended: in 1914, the Vatican had diplomatic relations with just fourteen states. After 1918, this number doubled, and included all of the European great powers except the Soviet Union.

John Pollard, University of Cambridge

Section Editor: Emmanuelle Cronier

Notes

- ↑ See Procacci, Giovanna: Soldati e prigionieri italiani nella grande guerra. Con una raccolta di lettere inedite, Rome 1993, especially pp. 149-159.

Selected Bibliography

- Carlen, Mary Claudia (ed.): The papal encyclicals, volume 4, Ann Arbor 1990: Pierian Press.

- Launay, Marcel: Benoît XV (1914-1922). Un pape pour la paix, Paris 2014: Cerf.

- Melloni, Alberto / Cavagnini, Giovanni / Grossi, Giulia (eds.): Benedetto XV. Papa Giacomo Della Chiesa nel mondo dell'inutile strage, 2 volumes, Bologna 2017: Il Mulino.

- Norton, R.: Benedict XV and the Save the Children fund, in: The Month 28/7, 1995, pp. 281-283.

- Pollard, John F.: The unknown pope. Benedict XV (1914-1922) and the pursuit of peace, London 1999: Geoffrey Chapman.

- Renoton-Beine, Nathalie: La colombe et les tranchées. Benoît XV et les tentatives de paix durant la Grande Guerre, Paris 2004: Cerf.