Introduction↑

Soon after the First World War (WWI) began, efforts commenced to end it through negotiations. Peace initiatives came from neutral governments, private citizens, and the belligerents themselves. Some aimed at a separate peace between two of the contending states; some at a general settlement to end the war altogether; and some, confusingly, involved parties seeking both a separate and a general peace at the same time. With the exception of Russia and Romania, each concluding a separate peace with the Central Powers in spring 1918, none of the peace initiatives launched prior to late 1918 succeeded in limiting or ending the war. They failed because the minimum terms acceptable to each side were incompatible. Each side perceived embracing the other side’s minimum terms as a “defeat” threatening their nation’s existence as an independent power or their domestic political stability. Moreover, accepting defeat seemed unnecessary, because until late 1918, neither side calculated that the military balance had rendered victory out of reach; both sides consistently believed that they had a reasonably good chance of achieving a military victory in the war great enough to allow them to impose at least their minimum terms on their opponents. In such circumstances, the costs of fighting on appeared less onerous than the costs of accepting defeat, and so the war continued.

Explaining Peace Initiatives, 1914-1916↑

Germany↑

In analyzing why major peace initiatives occurred, it is best to consider them in two distinct time periods: those from 1914 through 1916 and, secondly, those from early 1917 through early 1918. In the first time frame, Germany and the United States were the chief actors in trying to get some kind of peace talks going. In Germany’s case, its chief efforts were initially directed at France and especially Russia. Driven by their failure to achieve a decisive military victory in the first few weeks of the war and their concern that they could not win a long war against a united Allied coalition, German officials made contact with various French dissident figures from late 1914 through 1916, suggesting that France could have peace in exchange for giving Germany a war indemnity and perhaps colonial concessions. They especially focused on politicians close to ex-Minister President Joseph Caillaux (1863-1944), who they thought opposed the war and the existing French political system. The initiative for a separate peace with Russia likewise began in late 1914 and continued into 1915, peaking in late June and July. German leaders sent out peace offers to Nicholas II, Emperor of Russia (1868-1918) through Hans Niels Andersen (1852-1937), a shipping magnate and confidant of Christian X, King of Denmark (1870-1947), as well as to Russian ex-Premier Count Sergei Witte (1849-1915), who was rumored to be pro-German. Germany’s Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg (1856-1921) assured the Russians that Germany wanted “only small concessions in order to protect our eastern border, as well as financial and commercial treaties.”[1] Germany pursued still other contacts through family connections of the Tsar, stating that the Central Powers would allow Russia free passage of the Straits in exchange for peace.[2]

Germany’s approach toward peace negotiations took a new turn in late 1916. On 12 December, declaring that the Central Powers “have given proof of their indestructible strength in winning considerable successes at war,” Germany and its allies publicly called for peace negotiations with their enemies, stating no specific conditions or demands.[3] On its surface, this peace note appeared based on Germany’s confidence in its military position. In reality, the calculations behind it were more complicated. Bethmann Hollweg, the chief proponent of the initiative in the German government, thought time was not on Germany’s side in the war. At home, Germany’s largest political party, the Social Democrats (SPD), broke apart over supporting war credits in late 1914, and its majority faction, while still behind the war effort, increasingly demanded assurances that Germany wanted peace and fought only in self-defense, not for conquest. Germany’s chief ally, Austria-Hungary, also seemed weak and demoralized and, while Germany’s armies occupied enemy territory in the east and west, the Reich faced an Allied coalition with superior resources and a naval blockade that was slowly strangling Germany’s economy. Desperate to break the military stalemate, German military and naval leaders were anxious to begin unrestricted submarine warfare, a course Bethmann Hollweg feared would bring the United States and possibly other neutrals into the war on the Allied side. Bethmann Hollweg’s peace initiative aimed to relieve all of these domestic and international pressures on the Reich. If the Allies accepted Germany’s peace offer, unrestricted submarine warfare could be averted and negotiations would be based on the existing status quo, which heavily favored Germany. If they refused, which was likely, the Allies would be responsible for prolonging the war, not Germany. This would rally leftist Germans to the war effort and invigorate Austria-Hungary’s determination to fight. By highlighting Germany’s desires for peace and Allied intransigence, an Allied rejection of Germany’s peace offer might also increase the chances of neutral nations, including the United States, tolerating Germany’s unleashing of its submarines. Finally, Bethmann Hollweg expected that a refusal by the Allies to negotiate would spur anti-war sentiment in France and Russia, which might advance another effort to convince one or both of those countries to sign a separate peace with the Reich.[4]

The United States↑

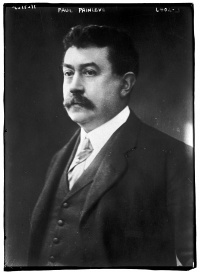

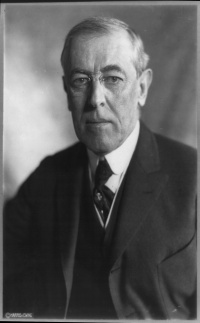

Very different motives lay behind the other major peace efforts of 1914-1916, those of President Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924) of the United States. The President early on saw himself as a potential mediator of the war. He repeatedly tried to prod the Germans and the British into a discussion of peace terms, usually on the basis of roughly the status quo ante bellum and post-war disarmament. On two occasions, in early 1915 and then again in early 1916, he sent his chief foreign policy advisor, Colonel Edward M. House (1858-1938) to Europe for face to face meetings with British, German, and French leaders, trying to find an avenue for wider talks or an opening for an American demand that hostilities cease. In May 1916, Wilson publicly endorsed U.S. participation in a post-war international security organization as a way to entice the belligerents into welcoming a U.S. mediation initiative. He followed this gambit up in December with a formal call for the belligerents to state the exact objects for which they fought and then, in January 1917, gave an impassioned plea that the war end with a “peace without victory” and the establishment of a “League of Peace” that would include the United States.[5]

Wilson’s desire to mediate an end to the war arose in part from his conception of America’s role in the world. The president deeply believed that the United States had a unique character among nations. Its exceptionalism, he argued, lay in the success of its democratic political system; its embracing of equality of opportunity for its citizens; its diverse population drawn from a wide variety of nations; and, lastly, its lack of territorial ambition and its detachment from the immediate causes of the war. These peculiarities, Wilson felt, made the United States a force for world progress; it had a “mission in the world...a mission of peace and goodwill.” If any country could and should bring the war to an end, it was the United States.[6]

Wilson’s view of U.S. national security also underlay his mediation efforts. He perceived that the longer the war went on, the more likely it was that the United States would get drawn into it, especially because of frictions with Germany over its submarine warfare. More basically, Wilson thought that balance-of-power politics had caused the war and that if power politics persisted after the war ended, eventually the United States would get caught up in its currents. The president was convinced that if either side of belligerents won a decisive victory, they would continue the arms races, alliances, and secret diplomacy that had fundamentally caused the war in the first place. Sooner or later, another global conflict would occur – and, Wilson warned his countrymen in October 1916, “this is the last war of the kind, or of any kind that involves the world, that the United States can keep out of.” By ending the war with the aims of each side frustrated. Wilson hoped the belligerents could be made to see that power politics had produced nothing but disaster and that the security of all nations, including the United States, would be best served through the creation of a new system of collective security, institutionalized in a league of nations.[7]

Explaining Peace Initiatives, 1917-1918↑

Austria-Hungary↑

More so than during the first two and one half years of the war, the period from early 1917 to early 1918 saw a flurry of significant peace efforts as the stalemate in the west continued and war weariness intensified in all the European belligerents. Austria-Hungary stood at the center of many of these episodes. Just before the United States entered the war in April 1917, the newly appointed Austrian foreign minister, Count Ottokar Czernin (1872-1932), conveyed to the American government Austria’s readiness for peace negotiations on the basis of a return to the status quo ante bellum. He urged President Wilson “to use his influence with the powers of the Entente to make them accept that basis” as well. Around the same time, the Austrian government also sent out peace feelers to the British, who responded by sending Sir Francis Hopwood (1860-1947) to Scandinavia to meet with Austrian representatives. Neither of these initiatives lasted very long, as it became clear Austria would not make peace without Germany agreeing to a settlement as well.[8]

A more sustained Austro-Hungarian peace effort involved Sixtus, Prince of Parma Bourbon (1886-1934), a member of the former French royal family who was serving in the Belgian army in 1916. Through his sister, who was married to Austria’s Charles I, Emperor of Austria (1887-1922), Sixtus had access to the highest levels of the Austro-Hungarian government. Shortly after he took the throne in late 1916, Charles asked his mother-in-law to establish contact with the French government; she used Sixtus to do so. French leaders told Sixtus that their terms included Alsace Lorraine, part of the Saar, “reparations, indemnities, and guarantees on the left bank of the Rhine.” Armed with this information, Sixtus eventually made his way to Vienna, where he met Charles in late March 1917. The Emperor seemed open to France’s demands. In a letter of 24 March given to Sixtus for delivery to the French, Charles agreed to restore Serbia, which had been overrun by the Central Powers in 1915; accepted that Belgium should also be restored; and pledged to support France’s “just claims” to Alsace-Lorraine. When the French received this missive, they informed the British, greatly exciting David Lloyd George (1863-1945), the British Prime Minister, who believed the Austrians might break with Germany and sign a separate peace with the Allies. When the French and the British informed the Italian government of the possibility of a peace with Austria, however, the Italian foreign minister, Baron Sidney Sonnino (1847-1922), made it clear that Italy expected all of its claims on Austria-Hungary to be fulfilled. If they were not, Italy might break with the Allied coalition and, Sonnino warned, revolution might engulf Italy. The Italian position effectively ended the Sixtus initiative, although another exchange of messages occurred from May to June.[9]

As the Sixtus contacts ground to a halt, another Austrian channel to France opened up. Count Nikolaus Revertera (1866-1951), a former Austrian diplomat with connections to the Austrian court, reached out to Count Abel Armand (1863-1919), an army officer in the foreign intelligence section of the French General Staff, in June 1917. Both men received authorization from their governments to meet; they held conversations in Switzerland in August. In these talks, Armand, apparently with the approval of French War Minister Paul Painlevé (1863-1933) but not the rest of the French leadership, did more than simply feel out Revertera’s views: he tried to entice Austria into a separate peace structured in part around France receiving Alsace-Lorraine and guarantees in the Rhineland, with Austria gaining territory from Germany. Charles was encouraged by these talks but Czernin had no interest in a separate peace with France; Armand did not receive an answer to his proposals.[10]

Finally, in late 1917 and early 1918, Austrian leaders again tried to explore the possibility of a general peace by making formal and informal contact with the Allies. These involved soundings to the British via Count Albert Mensdorff (1861-1945), former ambassador to London, and an Austrian diplomat in Sweden, and a revived exchange between Armand and Revertera. More significantly, they included a lengthy dialogue with the United States carried on through public statements by Wilson and Czernin; unofficial meetings in Berne between Austrian intellectual Heinrich Lammasch (1853-1920) and an American expatriate with ties to the diplomatic community, George D. Herron (1862-1925); and private communications from Charles to Wilson. These talks got into specific ideas about terms, including the status of Austria-Hungary’s various nationalities and French and Italian territorial claims. The exchanges went nowhere, however, as, yet again the Austrians were interested in a general peace, not a separate one, while the Allies were intent upon detaching Austria from its alliance with Germany.[11]

All of these Austro-Hungarian peace initiatives stemmed, fundamentally, from Charles’ and Czernin’s perception that the war threatened the existence of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The war severely traumatized the Empire’s economy, producing catastrophic food and fuel shortages and inflation; devastated its manpower; exacerbated political tensions between Austria and Hungary; and stimulated the nationalist aspirations of the Empire’s ethnic groups. The weaker the Empire became, the more it depended upon Germany, to the point that Charles feared the Germans viewed Vienna as little more than a satellite of the Reich. “A smashing German victory,” Charles noted in a draft letter to Czernin in May 1917, “would be our ruin.” Czernin may not have gone as far as Charles in this view, but he certainly sensed that the war was eroding Austria-Hungary’s independence as a great power. To get peace, Czernin tried to convince Germany to moderate its aims in the war while at the same time seizing whatever chance he could to signal the Allies that Austria was open to a general peace settlement based upon the status quo ante bellum or minor frontier changes. Even more desperate to get out of the war than Czernin, Charles sometimes – as in the Sixtus affair – pursued contacts with the Allies more fervently than his foreign minister. This tended to give false encouragement to the Allies that Austria was interested in a separate peace, which helps to explain why the French, British, and Americans so readily responded to Austrian overtures. Ultimately, though, Charles deferred to Czernin’s commitment to pursuing peace only within the framework of maintaining the alliance with Germany.[12]

Germany↑

The Germans, for their part, continued to be open to the possibility of a separate peace with one or more of the Allies. Their most important initiative to the west occurred in the wake of Pope Benedict XV’s (1854-1922) peace appeal, published by the Vatican on 1 August 1917. Moved to act by some encouraging words from Bethmann Hollweg to Vatican diplomats about Belgium and Alsace-Lorraine, a sense of religious duty, and a fear that Europe was committing “suicide,” the Pope essentially called for a peace based upon a return to 1914 frontiers without annexations or indemnities. The leading belligerents either ignored the Pontiff or made negative replies, except for Great Britain. British leaders, increasingly pessimistic about their ability to win a decisive victory that would destroy Germany’s military autocracy, decided to use Benedict’s appeal to feel out Germany about its readiness to restore Belgium, a central British war aim. They sent a letter to London’s representative at the Vatican noting that Germany’s intentions with regard to Belgium were unclear; Vatican officials, in turn, forwarded this message to Berlin.[13]

Confronted with the British inquiry, Richard von Kühlmann (1873-1948), Germany’s recently installed foreign secretary, decided to act. He did so because of rising peace sentiment in Germany among the liberal and socialist parties; concern that the Austrians, then in the midst of the Armand-Revertera conversations, might pursue a separate peace of their own; and a belief that Britain wanted out of the war, even if it meant making major concessions to the Germans. On 11 September, German leaders agreed marginally to scale back the economic and strategic guarantees they wanted in Belgium, especially by giving up the German navy’s demands for permanent bases along the Flanders coastline. This stance gave Kühlmann something to offer the British; he proceeded to send a version of the new German position to the Spanish minister in Brussels, the Marquis de Villalobar (1864-1926), for transmission to London. Villalobar told his own superiors, who notified the British ambassador in Madrid that high-level German officials were interested in peace communications – a more ambiguous message than Kühlmann intended.[14]

British leaders divined that Germany seemed open to some sort of deal in the west, however, as they received Kühlmann’s initiative at the same time as they heard of another German peace feeler to the French. This contact involved Baron von der Lancken, chief of the political department of the German occupation administration in Belgium. Back in April 1917, when revolution in Russia appeared to weaken the Allied coalition, German leaders had authorized Lancken to renew Germany’s earlier attempts to talk to French politicians regarding peace. To entice them, Lancken was told to offer token concessions on Alsace-Lorraine. Once embarked on his mission, he exceeded his instructions and indicated Germany was ready to give up a lot more on issues in the west. Lancken eventually contacted Aristide Briand (1862-1932), a former French prime minister, who agreed in principle to meet in Switzerland in mid-September. French leaders were not entirely certain of Lancken’s legitimacy and in any case were wary of engaging in talks that might divide the Allied coalition. They therefore informed the British of the Lancken contact, leaving British foreign secretary Arthur Balfour (1848-1930) with the impression that Germany was interested in negotiations on Belgium and Alsace-Lorraine, as well as on its colonies and Serbia.[15]

Over the next three days, British leaders consulted with the French and with each other about the Lancken and the still-secret Villalobar initiatives. They perceived Germany’s soundings as essentially an offer to make concessions in the west in exchange for a free hand in Eastern Europe and Russia. In the deliberations, Lloyd George, concerned that the bloodbath of the war was sapping Britain’s strength, appeared tempted by such a deal, but his colleagues were not, for reasons discussed below. On 6 October the British told their allies, including Russia, of the Villalobar contact, and replied to Germany that they were willing to listen to peace communications, but any messages had to be discussed with their alliance partners. Kühlmann, who was only interested in splitting Britain from its coalition by offering minimal concessions in the west, then declared in public that Germany would never cede Alsace-Lorraine. With that, the “Kühlmann peace kite” fluttered to the ground.[16]

Russia↑

The collapse of Tsarist Russia loomed large over all the peace initiatives of 1917 and early 1918. It increased French and British interest in peace feelers from Germany and especially Austria-Hungary while heightening peace sentiment among socialists in all the European belligerent nations. Most significantly, the new Russian Provisional Government and the center of the revolution’s authority, the Petrograd Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies, engaged in wide ranging peace efforts of their own. One channel involved contacts between the Provisional Government and Germany. In early 1917, Bethmann Hollweg saw Russia’s revolution as an opportunity to end the war in the east on terms favorable to Germany. To explore the possibility of a separate peace, he allowed talks to proceed between Matthias Erzberger (1875-1921), the leader of the left wing of the Center Party, and a Russian diplomat, Joseph von Kolyshko, in Stockholm in March-April 1917. The deal worked out between them in part called for restoring Russia’s pre-1914 border, perhaps with some frontier changes, and for creating a new Polish state that would hold a plebiscite to determine whether or not it would be under Russian sovereignty. Bethmann Hollweg had more demanding terms in mind, however. He and other civilian leaders in Germany wanted Poland and the Baltics to be “autonomous” – free from Russian control – and open to German economic influence and ethnically German settlement. Germany’s military leaders wanted the outright annexation of Courland and Lithuania as well as other frontier adjustments at Russia’s expense. With the Russians less eager for a separate peace than a general one and in any case hopeful of keeping their western borderlands in their sphere of influence, even Bethmann Hollweg’s more moderate terms doomed the Erzberger-Kolyshko talks as well as other German-Russian contacts.[17]

The Russians campaigned for a general peace along two separate but inter-related tracks. On one, the Provisional Government tried to convince the Allies to join in an inter-Allied conference to revise war aims. The Russians specifically wanted their partners to join them in working for an end to the war on the basis of the “Petrograd formula” – a peace “without annexations or indemnities...based on the rights of nations to decide their own affairs.” In addition to this governmental effort at war aims revision, the Petrograd Soviet on 15 May 1917 called for a negotiated peace and for socialists in the belligerent states to force their governments to end the war on the basis of the Petrograd formula. It urged all socialists to send representatives to Stockholm for a conference on how to achieve this goal.[18]

The calculations and relationship between these two tracks was complicated. Most basically, the Russian people’s desire for peace was a primary cause of the revolution; no revolutionary leadership could ignore that sentiment and expect to stay in power. At the same time, neither the Provisional Government nor the Soviet wanted peace at any price and all leading political parties opposed a separate peace with the Central Powers. Russian leaders thought that a separate settlement with Germany would have devastating results for their country. It would probably allow Germany to win the war in the west, leaving Russia with a powerful enemy right on its border; turn Russia into a virtual German colony; and perhaps lead to a restoration of the Tsar. The dual-track peace program, in contrast, maximized chances for a quick negotiated end to the entire war. The Stockholm conference would hopefully spur socialist and liberal elements in the Allied nations to pressure their governments into formally embracing the Petrograd formula. Once that happened, the governments of the Central Powers would see that negotiations were possible and, pressured by their own leftist groups at home, they would embrace talks to stop the fighting.[19]

Neither the Stockholm conference nor Allied war aims revision got very far. The Allies saw little reason to negotiate with the Provisional Government over war aims when Russia’s contribution to the Allied war effort was lagging. They also feared an open discussion of war aims would undermine their public’s will to fight. They therefore largely ignored the Provisional Government’s attempt to get them to hold an inter-Allied meeting on peace terms. The Allies also had little difficulty sabotaging the Stockholm conference. Even socialists within the Allied nations were divided over the wisdom of the conference and hesitated to endorse it. The British government was at first willing to allow Labour Party members to attend, but only as a gesture to encourage Russia to stay in the war. Once the United States, Italy, and France undercut Stockholm by refusing to issue passports to socialists who wanted to go, Britain did the same thing. As for Germany, Erzberger and the Center Party, the Progressives, and the SPD joined together to pass a “peace resolution” in the Reichstag in July 1917 that vaguely echoed the Petrograd formula. It sharpened Germany’s domestic political divisions over war aims, but it had little practical impact on German foreign policy. While German leaders did allow the SPD to go to Stockholm, they only did so to keep the party loyal to the war effort. Seeing their peace program in trouble, the Russians attempted a military offensive in early July 1917, hoping to enhance their diplomatic influence abroad. The offensive failed badly, however, fatally undermining the Russian peace effort.[20]

The Bolsheviks and Peace by Capitulation↑

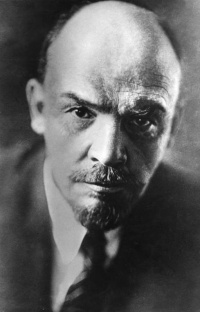

Within months of the collapse of the July 1917 offensive, the Bolsheviks led by Vladimir I. Lenin (1870-1924) took power in Russia. From November 1917 to early January 1918, they repudiated traditional diplomacy, concluded an armistice with the Central Powers, and tried to use peace negotiations at Brest-Litovsk as a propaganda platform to spark socialist revolutions in all the belligerents. No revolutions occurred, however. The Allies moderated their publicly stated war aims to a minimal degree to rally their publics to the war effort and refused to join in the peace talks between the Central Powers and the Russians. At the Brest-Litovsk negotiations, the Germans at first put forward a program designed to “stage-manage” the self-determination of Russia’s borderlands in a way that assured German domination of them. When the Bolsheviks balked at accepting these terms, the Germans resumed their military advance into Russia, which convinced the Bolshevik government to give up the war. Led by Lenin, the Bolsheviks decided that continued fighting was fruitless and would undermine their hold on power. On 3 March 1918, they signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with the Central Powers, yielding sovereignty over a vast area containing some 55 million people. A few weeks later, the Central Powers imposed a similarly onerous peace treaty on Romania.[21]

Explaining the Failure of Peace Initiatives: Perceptions of the Cost of Defeat↑

The Allies↑

Peace initiatives prior to the peace of conquest at Brest-Litovsk foundered in part because each of the chief belligerents perceived the stakes in the war as involving, in one way or another, their continued survival as independent great powers or the survival of their domestic political systems or both. To British leaders, German aggression, embodied in the Reich’s Prussian military caste, caused the war. Germany hoped to dominate Europe and, in British eyes, it could do so if it retained its control of Belgium and reduced France, though territorial and financial demands, to the status of a second rate power. If that happened, Britain would face a powerful enemy directly across from its coast; Britain would be vulnerable to German intimidation and unlikely to win another war with Germany should one break out. Indeed, most British leaders throughout the war believed that any increase in Germany’s pre-1914 power unacceptably increased these risks. Britain’s minimum terms for ending the war were therefore the restoration of the status quo ante bellum in the west and, for most British leaders, sharp limits to any German gains in the east.[22]

France had a similarly existential view of the war. The Reich’s early success on the western front, which left it in occupation of much of northern France, highlighted for French leaders a stark power imbalance between Germany and France. If France submitted to the Germans, they would enhance their power still more, by taking permanent control of French coal and iron fields in the north and by bankrupting it with a massive war indemnity. France might survive, but only as a satellite of Germany. Any compromise peace that left Prussian militarism intact and its power enhanced by gains in the east was little better in French eyes, as it left France ill-prepared to win any future war with the Reich. Hence, to preserve its existence as an independent great nation, French leaders believed they had to redress the balance of power against Germany by, at the very least, expelling the Germans from all of French territory and restoring Belgium; regaining some of Alsace-Lorraine; and attaining some sort of security guarantee in the Rhineland.[23]

In the United States, after Germany’s unrestricted submarine warfare in early 1917 led President Wilson to enter the war, U.S. leaders no longer saw a “peace without victory” as possible or desirable. Wilson now considered the Reich a dangerous, relentlessly ambitious enemy. In his view, Germany’s military masters aimed to dominate Europe and make Germany an armed power without peer. If they succeeded, the United States would have no choice but to arm itself as never before, to prepare for Germany’s next bid for conquests. In such an insecure environment, Wilson argued, America’s domestic political freedoms would never survive. He therefore demanded that Germany not only be denied any gains from the war, but also that its power be reduced to below its pre-1914 level.[24]

Italy and pre-Bolshevik Russia likewise perceived enormous stakes in the war. The Italians thought that Italy’s future security and the stability of its monarchy depended upon making territorial gains in the north and along the Adriatic coast. Tsarist Russia’s leaders made a similar calculation: failure to attain some tangible gains from the war in Poland and in the Ottoman Empire would result in a revolution fatal to autocratic rule. For the Provisional Government, salvation lay not in annexations but in preventing Germany from imposing its will upon Britain and France. The leaders of both the government and the Soviet perceived that if Germany defeated the Allies, the Reich would turn all of its power eastward and destroy the revolution, by turning Russia into a German satellite and restoring the Tsar. Making any peace with Germany that would allow it to focus on the western front was thus out of the question.[25]

The Central Powers↑

Austria-Hungary wanted to get out of the war as much as revolutionary Russia. But it refused to break its alliance with Germany to accomplish this end. Czernin and, ultimately, Charles, considered the German alliance to be more crucial to Austria-Hungary’s survival than peace, however painful the war might be. If Austria abandoned Germany and the Allies won the war, Austrian leaders feared the Entente would break whatever promises it had made to get peace and would allow Romania, Italy, and Serbia to partition Austrian territory. Breaking the alliance could also lead to a German invasion or a destabilizing cut-off of German economic aid. With the tie to Berlin no longer buttressing the authority of the monarchy, Austria’s restive nationalities, if they did not simply revolt, would demand extensive autonomy and other political reforms. The ruling Austrian-German and Magyar groups might then find themselves at the mercy of a Slav majority. For Austria-Hungary’s leaders, this meant the end of their state as they knew it. However much staying in the war seemed to endanger Austria-Hungary, a separate peace appeared to be a riskier alternative to Czernin and Charles.[26]

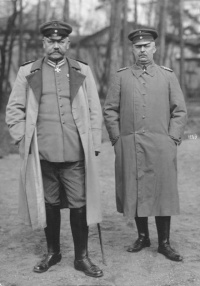

For German leaders, the war represented an opportunity to achieve, in Bethmann Hollweg’s secretary’s words, “security for the German Reich in the west and east for all imaginable time.” Generals Erich Ludendorff (1865-1937) and Paul von Hindenburg (1847-1934), Germany’s predominant policymakers after August 1916, saw endless warfare as inevitable; Germany therefore had to be well positioned for the post-war period so that it could withstand any possible future attack. Germany’s authoritarian leaders also feared that if they did not deliver concrete territorial and economic rewards to the German people from the war, domestic support for Germany’s autocracy would collapse. A peace based upon the status quo ante bellum would not achieve these aims. To Germany’s leaders, only German dominance over Europe could achieve them. Civilians like Bethmann Hollweg and Kuhlmann and German military leaders disagreed over the exact form this dominance should take, but all of them agreed that preserving the Reich’s security and its domestic political system demanded nothing less than German hegemony over the continent. This view made them hostile to any peace initiative that did not in effect ratify a German victory in the war.[27]

Explaining the Failure of Peace Initiatives: The Expectation of Victory↑

1914-early 1917↑

The existential political stakes that each side saw in the war were not the only reasons for the failure of compromise peace efforts. Peace initiatives also failed because until the last months of the war, neither side ever really lost confidence that they could prevail over their opponents by force. From late 1914 to early 1917, the Allies thought the balance of power favored them because they had access to greater resources than the Central Powers. Soon after the war started, Britain effectively limited Germany’s overseas trade with a naval blockade. Britain, in contrast, could draw not only on the resources of its empire, but also, because of President Wilson’s decision to allow supplies and loans to flow across the Atlantic, on the vast wealth of the United States. The Allies also got Italy to join their side in 1915. On the battlefield, French and British leaders were confident that while Germany held an existing advantage, they were slowly wearing Germany down; British leaders in particular looked forward to smashing Germany’s will to resist with a massive offensive in July 1916 at the Somme. With this outlook, they had no interest in peace talks in the first two years of the war.[28]

The Germans recognized that the Allies had a resource advantage over them; this was the primary reason they tried to split the Allied coalition with peace offers in 1915 and early 1916. But with its armies in possession of enemy territory in both the east and west, and the Allies evidently unable to push them out, German leaders saw no reason to offer extensive concessions to their enemies. In 1916, Germany suffered some setbacks in the war, as the Russians had some success in an offensive against Austria-Hungary and the Allies inflicted enormous losses on the Germans at Verdun and the Somme. Yet the Reich’s military situation never became desperate. It still occupied Belgium and northern France; it contained Russia’s advance in the east; and, late in the year, it occupied much of Romania, including Bucharest. Germany's hopes for victory were also fueled by its anticipation of launching a campaign of unrestricted submarine warfare. Naval leaders throughout 1916 promised that such a campaign could force Britain to negotiate on German terms within six months. They discounted the effect American entry could have on the war by arguing that Wilson’s trade policies made the United States anti-German in any case and predicting that the war would be over before the U.S. could make its weight felt on the Allied side. Not all German policymakers were as confident in these predictions as the Reich’s admirals. But they thought the submarine campaign might work as advertised. Fearing the high costs they associated with a compromise peace, that hope was enough for them to spurn Wilson’s mediation effort and unleash their U-boats.[29]

1917-early 1918↑

From early 1917 to early 1918, two new developments operated to maintain each side’s hopes for victory. First, the entry of the United States into the conflict in April 1917 helped the Allies to withstand their most difficult year of the war. The U.S. rescued the Allies financially, provided assistance that allowed them to defeat the U-boat campaign, and began to send combat troops to France in slow, but growing numbers, just as Russia’s fighting ability collapsed in the east. All of this aid reinforced Allied morale. As Britain’s top military leader noted at the time of Britain’s refusal to join the Brest-Litovsk peace negotiations, “with the vast potential supply of men in America there should be no doubt of our winning.” Conversely, the collapse of Russia and its exit from the war, which began in earnest as the failure of the submarine warfare campaign became apparent, kept alive Germany’s optimism that it could escape defeat. Events in Russia combined with the delay in the deployment of large numbers of American troops to France led General Ludendorff, in January 1918, to decide that conditions were ripe for an all-out attack in France to compel the Allies to meet Germany’s terms in the west. Germany had to act quickly, before the Americans arrived in force, but if it did, it could still avoid defeat. Victory in the east thus led German leaders to focus not on the possible merits of a compromise peace with the remaining members of the Allied coalition, but on the window of opportunity they thought they had in the west to win the war.[30]

Conclusion↑

Peace initiatives during World War I never had much chance of success. Three reasons stand out for why this was so. First, both sides suffered from a profound sense of insecurity. They were trapped in an anarchic international system long characterized by uncertainty, arms races, warfare, and constant intrigue. Both sides tended to assume the worst in their enemies; both trusted in the reduction of their opponents’ power, more than anything else, to keep them safe. So long as they could believe that they had a plausible chance to prevail on the battlefield, they would not abandon their quest to achieve that goal. Secondly, the character of the German government, especially after Ludendorff and Hindenburg consolidated their power after July 1917, made a peace based upon the status quo ante bellum – the terms most likely to end the fighting – almost impossible. Germany’s military leaders consistently opposed even the indirect forms of German expansion advocated by Bethmann Hollweg and Kühlmann as inadequate for Germany’s security, were completely convinced that only the most extensive gains possible could fend of revolution at home, and, at crucial turning points in the war, always advocated high-risk gambles for victory rather than seriously explore peace possibilities. Finally, the policies of the United States helped to prolong the war. In the neutrality period, Wilson chose to acquiesce in Britain’s blockade and trade with the Allies while confronting Germany over its submarines. In effect, whatever Wilson’s motives, this stance helped to fuel the Allied war effort while discrediting the United States as a potential mediator. After the U.S. entered the conflict, it provided enough help to the Allies to keep them willing to fight while being so slow to get its army into action that Germany could still think it could win. For all of these reasons, the war became absolute – a fight to the finish where only the impending invasion of German soil by Allied forces could end it.

Ross A. Kennedy, Illinois State University

Section Editor: Holger Afflerbach

Notes

- ↑ Farrar, Jr., L.L.: Divide and Conquer. German Efforts to Conclude a Separate Peace, 1914-1918, Boulder 1978, p. 18.

- ↑ See Farrar, Divide and Conquer 1978, pp. 13-56; Stevenson, David: The First World War and International Politics, New York 1988, pp. 92-95; Fischer, Fritz: Germany’s Aims in the First World War, New York 1961, pp. 184f, 189.

- ↑ Proposals for Peace Negotiations Made by Germany, in: Scott, James Brown (ed.): Official Statements of War Aims and Peace Proposals, Washington 1921, p. 2.

- ↑ Farrar, Divide and Conquer 1978, pp. 67-70; Fischer, Germany’s Aims 1961, pp. 285, 290, 293-97; Jarausch, Konrad H.: The Enigmatic Chancellor. Bethmann Hollweg and the Hubris of Imperial Germany, New Haven/London 1973, pp. 210ff, 226, 231, 235, 250-53. For a full discussion of the submarine issue, see: Birnbaum, Karl E.: Peace Moves and U-Boat Warfare. A Study of Imperial Germany’s Policy Toward the United States, April 18, 1916 – January 9, 1917, Uppsala 1958.

- ↑ Kennedy, Ross A.: The Will to Believe. Woodrow Wilson, World War I, and America’s Strategy for Peace and Security, Kent 2009, pp. 68f, 71-74, 86-89. 94-98.

- ↑ Kennedy, Will to Believe 2009, pp. 47f.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 33 and see 1-64, passim.

- ↑ Mamatey, Victor S.: The United States and East Central Europe, 1914-1918. A Study in Wilsonian Diplomacy and Propaganda, Princeton 1957, p. 55 and see pp. 54-62, passim; Rothwell, V. H.: British War Aims and Peace Diplomacy. 1914-1918, Oxford 1971, pp. 79f.

- ↑ Stevenson, David: French War Aims Against Germany. 1914-1919, Oxford 1982, p. 58; Stevenson, International Politics 1988, p. 142 and see pp. 117, 141ff. See also Rothwell, British War Aims 1971, pp. 83-87; Burgwyn, H. James: The Legend of the Mutilated Victory. Italy, the Great War, and the Paris Peace Conference, 1915-1919, Westport 1993, pp. 101ff.

- ↑ Shanafelt, Gary W.: The Secret Enemy. Austria-Hungary and the German Alliance, 1914-1918, Boulder 1985, p. 145; Stevenson, French War Aims 1982, pp. 72-75.

- ↑ Shanafelt, Secret Enemy 1985, pp. 181-84; Mamatey, United States and East Central Europe 1957, pp. 195ff, 219-32; Rothwell, British War Aims 1971, pp. 160-71.

- ↑ Shanafelt, Secret Enemy 1985, p. 104 and see pp. 98-101, 108ff, 116, 122f, 129, 137, 182ff. See also Stevenson, International Politics 1988, pp. 140, 148.

- ↑ Peace Proposal of Pope Benedict XV, in: Scott (ed.), Official Statements 1921, p. 129; Rothwell, British War Aims 1971, pp. 102-05; Fest, W. B.: British War Aims and German Peace Feelers during the First World War, The Historical Journal 15 (1972), pp. 299f; Forster, Kent: The Failures of Peace. The Search for a Negotiated Peace During the First World War, Washington 1941, pp. 126-34; Stevenson, David: Cataclysm. The First World War as Political Tragedy, New York 2004, pp. 290f.

- ↑ Farrar, Divide and Conquer 1978, pp. 88f; Fischer, Germany’s Aims 1961, pp. 420-26; Fest, British War Aims 1972, pp. 300f; Stevenson, International Politics 1988, pp. 164f; Stevenson, David: The Failure of Peace by Negotiation in 1917, The Historical Journal 34 (1991), p. 80.

- ↑ Rothwell, British War Aims 1971, pp. 105f; Fest, British War Aims 1972, p. 301; Stevenson, International Politics 1988, pp. 166f; Stevenson, Failure of Peace 1991, pp. 80f.

- ↑ Woodward, D.R.: David Lloyd George, a Negotiated Peace with Germany, and the Kuhlmann Peace Kite of September 1917, Canadian Journal of History 6 (1971), pp. 75-93; Stevenson, International Politics 1988, pp. 167f; Rothwell: British War Aims 1971, pp. 105-09; Fest, British War Aims 1972, pp. 300-03; French, David: The Strategy of the Lloyd George Coalition. 1916-1918, Oxford 1995, pp. 144-47.

- ↑ Fischer, Germany’s Aims 1961, pp. 374-88; Jarausch, Enigmatic Chancellor 1973, pp. 258f; Shanafelt, Secret Enemies 1985, pp. 134ff; Stevenson, International Politics 1988, pp. 150ff; Kitchen, Martin: The Silent Dictatorship. The Politics of the German High Command under Hindenburg and Ludendorff, 1916-1918, New York 1976, pp. 101ff.

- ↑ Wade, Rex A.: The Russian Search for Peace. February-October 1917, Stanford 1969, pp. 51, 26-56.

- ↑ Wade, Russian Search 1969, pp. 74, 90, 145f; Kirby, David: War, Peace, and Revolution. International Socialism at the Crossroads, 1914-1918, New York 1986, p. 113.

- ↑ Burgwyn, Legend of the Mutilated Victory 1993, p. 105; Rothwell, British War Aims 1971, pp. 96-100; Stevenson, International Politics 1988, pp. 152-60; Stevenson, French War Aims 1982, pp. 68-71; Wade, Russian Search 1969, pp. 57, 61, 68-71, 105, 115; Kirby, International Socialism 1986, pp. 105ff, 152f, 155; Kitchen, Silent Dictatorship 1976, pp. 137f; Fischer, Germany’s Aims 1961, pp. 388ff, 394-403.

- ↑ Stevenson, International Politics 1988, p. 187 and pp. 189-99, 201, 203f; Debo, Richard K.: Revolution and Survival. the Foreign Policy of Soviet Russia, 1917-1918, Toronto 1979, pp. 15-18, 27-31, 47ff, 50-55, 65, 69, 79, 112, 122f, and see 52-161, passim; Fischer, Germany’s Aims 1961, pp. 475-82.

- ↑ Rothwell, British War Aims 1971, pp. 3-24, 53, 65, 104-10, 148-53, 162f, 190; Stevenson, International Politics 1988, pp. 35-36, 107-10, 168, 181, 192f; Goemans, H.E.: War and Punishment. The Causes of War Termination and the First World War, Princeton 2000, pp. 190, 206ff, 225-29; French, Lloyd George Coalition 1995, pp. 3-6, 34ff, 139, 145ff, 157, 202f; Jaffe, Lorna S.: The Decision to Disarm Germany. British Policy towards Postwar German Disarmament, 1914-1919, Boston 1985, pp. 7-13, 22f, 28f, 39, 42ff, 56.

- ↑ Goemans, War Termination 2000, pp. 134f, 164-78; Stevenson, French War Aims 1982, pp. 7-12, 17, 38f, 42f, 47-54, 63-70, 77, 92f, 201f, 207-11; Farrar, Divide and Conquer 1978, pp. 55f.

- ↑ Kennedy, Will to Believe 2009, pp. 128-39.

- ↑ Stevenson, International Politics 1988, pp. 49, 52-56; Burgwyn, Legend of the Mutilated Victory 1993, pp. 10-13, 15, 18ff, 27ff, 102, 104f; Goemans, War Termination 2000, pp. 128-32, 244f; Wade, Russian Search 1969, pp. 69ff, 90, 143.

- ↑ Shanafelt, Secret Enemy 1985, pp. 43, 152-59, 208.

- ↑ Stevenson, Cataclysm 2004, p. 105 and pp. 105-09; Kitchen, Silent Dictatorship 1976, pp. 100, 102f, 106, 159-66, 168f, 172; Goemans, War Termination 2000, pp. 74-77, 85, 106, 109f; Craig, Gordon A.: Germany. 1866-1945, New York 1978, pp. 358-66, 382; 392f; Shanafelt, Secret Enemy 1985, pp. 71-76; Stevenson, International Politics 1988, pp. 89-106, 145-55, 165f, 168f, 186-89; Farrar, Divide and Conquer 1978, pp. 49f, 68ff, 83-95, 102-19; Jarausch: Enigmatic Chancellor 1973, pp. 183-93, 200f, 218f, 223f, 228, 263; Chickering, Roger: Imperial Germany and the Great War. 1914-1918, Cambridge 2004, pp. 62f, 159, 167ff.

- ↑ Kennedy, Will to Believe 2009, pp. 65-75, 80-86; Rothwell, British War Aims 1971, p. 33; French, Lloyd George Coalition 1995, pp. 4f; Stevenson: Cataclysm 2004, pp. 113, 122; Ferguson, Niall: The Pity of War. Explaining World War I, New York 1999, pp. 292f.

- ↑ Farrar, Divide and Conquer 1978, pp. 6-43, 49f, 116; Kennedy, Will to Believe 2009, pp. 72f; Chickering, Imperial Germany 2004, pp. 52-59, 66-71; Stevenson, Cataclysm 2004, pp. 139, 212ff; Birnbaum, Peace Moves 1958, pp. 134, 322; Goemans, War Termination 2000, pp. 95-98.

- ↑ French, Lloyd George Coalition 1995, p. 202 and pp. 92, 156; Stevenson, Cataclysm 2004, pp. 254, 265, 267-78, 296f, 308-11, 328; Wade, Russian Search 1969, pp. 91, 145f; Stevenson, International Politics 1988, pp. 170, 189; Goemans, War Termination 2000, pp. 259-65; Stevenson, David: With Our Backs to the Wall. Victory and Defeat in 1918, Cambridge 2011, pp. 31-41.

Selected Bibliography

- Calleo, David P: The German problem reconsidered. Germany and the world order, 1870 to the present, Cambridge; New York 1978: Cambridge University Press.

- Herwig, Holger H.: The First World War. Germany and Austria-Hungary, 1914-1918, London; New York 1997: Arnold; St. Martin's Press.

- Mearsheimer, John .: The tragedy of Great Power politics, New York 2001: Norton.

- Millman, Brock: Pessimism and British war policy, 1916-1918, London; Portland 2001: Frank Cass.

- Ritter, Gerhard: The sword and the scepter. The problem of militarism in Germany, volume 4, Coral Gables 1973: University of Miami Press.

- Snell, John L.: Wilson's peace program and German socialism, January-March 1918, in: The Mississippi Valley Historical Review 38/2, 1951, pp. 187-214.

- Strachan, Hew: The First World War, New York 2003: Viking.

- Woodward, David R.: Britain’s Brass-Hats and the Question of a Compromise Peace. 1916-1918, in: Military Affairs/35 , 1971, pp. 63-68.