Introduction↑

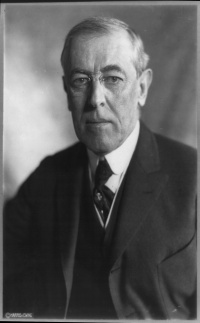

For Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924) and other advocates of regional integration with Latin America, the onset of World War I created new opportunities to pursue Pan American initiatives within the Western Hemisphere. The emphasis on Pan Americanism embraced broadly conceived political and economic goals stressing peacekeeping, trade expansion, the containment of anti-capitalist revolution, and the exclusion of European presence. Wilson’s plans gave special prominence to the “ABC” countries, that is, Argentina, Brazil and Chile. They achieved mixed levels of success and failure. Latin American resistance doomed some of his efforts to change political relations. However, in the economic realm, the consequences of the war reduced traditional European dependencies and created new opportunities for trade and investment by the United States.

“The Western Hemisphere idea,” as the historian Arthur P. Whitaker (1895-1979) called it in his classic work, always appealed more to enthusiasts in the United States than in Latin America. For Latin Americans, talk of international solidarity meant something primarily among themselves as Hispanics. Going back to Simón Bolívar (1783-1830), they recognized more clearly than “gringos” the distinctiveness of their own histories, traditions, and cultures and preferred to remain aloof from the feared, sometimes detested “Colossus of the North.” Nevertheless, after the U.S. Civil War, international structural changes posed new dangers difficult to evade. The transformation of the United States into an industrial giant and the ensuing outward thrust into Mexico, Central America, the Caribbean, and elsewhere meant an elevated sense of menace and insecurity, and Wilson’s Pan American visions appeared to present carefully veiled threats.

Wilson and Foreign Affairs↑

As president, Wilson operated outside the usual mold. As an academic with a Ph.D. in political science, he had served as the head of Princeton University and as a one-term governor of New Jersey. Otherwise he lacked experience in national and international politics. As a scholar, his work centered on domestic affairs, and as a political leader he thought of himself as a progressive reformer. As he once anticipated presciently, it was ironic that he had to deal mainly with diplomatic issues. Indeed, while in office he became more involved with questions of war and revolution than had any president since the wars of the French Revolution and Napoleon.

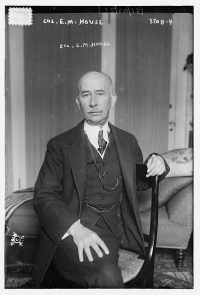

When the Great War broke out in August 1914, international troubles cascaded down on President Wilson. He responded by declaring U.S. neutrality but had difficulty sustaining it. German and British violations occurred repeatedly and meant constant danger. Moreover, concerns over the possibility of German intrusions into the New World contributed to military interventions in Mexico, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic and led to an aroused advocacy of Pan Americanism. Edward M. House (1858-1938), known to his associates as “Colonel,” became a chief proponent.

Pan American Initiatives↑

A rich Texan from Houston and a political insider, House functioned as a privileged adviser with special access to the president, even though he had no official status. Something of an intellectual, he had written a utopian novel, Philip Dru: Administrator (1912), in which he set forth his view of how governments ought to function in support of the public good. Beginning in November 1914, House pressed Wilson to pay greater attention to Latin America, where “the Big Stick” had alienated elites and given Europeans an advantage. House wanted a more intimate relationship, an amalgamation of nations in the form of a Pan American Pact providing for a regional collective security system. Among other things, it would provide for compulsory arbitration of hemispheric disputes and institute a multilateral definition of the Monroe Doctrine. House elaborated on his idea in late December 1914 when he exhorted Wilson to play a major role in resolving the European catastrophe by establishing a new international system to guarantee peace, territorial integrity, political independence, and republican forms of government.

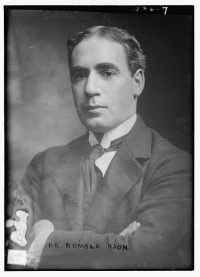

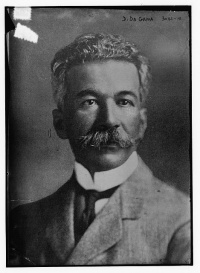

Wilson authorized House to engage the ambassadors from “the ABC countries” in preliminary discussions. He received a mixed response. Romulo S. Naón (1875-1941) from Argentina and Domício da Gama (1862-1925) from Brazil thought the idea had merit, but Eduardo Suárez Mújica (1859-1922), the Chilean ambassador, objected to it. This was presumably out of concern for potential adverse effects on an ongoing controversy with Peru over the status of Tacna and Arica, both nitrate-rich provinces annexed by Chile during the War of the Pacific. Suárez Mújica also raised concerns about infringements on national sovereignty and the possibility of inviting new forms of U.S. intervention.

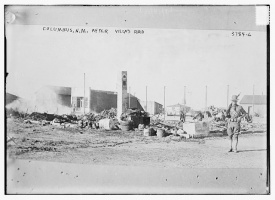

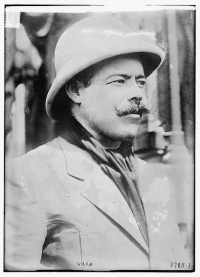

These discussions continued intermittently during the next year but never had much chance for success. This was in part due to the complexities arising from the Mexican Revolution, which raised many questions about Wilson’s intentions. Though the president spoke in defense of democracy and self-determination, his actions suggested other priorities. Witness the “intervention” at Veracruz in April 1914 in an effort to overthrow the tyrant and usurper Victoriano Huerta (1850-1916). When Huerta fell from power, his main opponents in the Constitutionalist coalition fell out among themselves and into a civil war. When in response Wilson attempted to employ a kind of Pan American response by inviting “the ABC countries” together with Bolivia, Guatemala, and Uruguay to a conference for the purpose of extending diplomatic recognition, the choice fell on Venustiano Carranza (1859-1920) in October 1915. His rival, Francisco Villa (1878-1923) responded in March 1916 by attacking Columbus, New Mexico. Wilson, in turn, sent the Pershing Expedition in Mexico to punish him.

Political Consequences↑

This act, carried out unilaterally, ruined Wilson’s Pan America initiatives for Latin Americans who could not believe in his sincerity of purpose or his truthfulness. For them, previous unilateral interventions in Haiti and the Dominican Republic validated their misgivings. For his part, President Carranza subsequently issued a statement, the Carranza Doctrine, which placed an absolute prohibition on foreign intervention in Mexico for any purpose and by any means whatsoever. For Carranza, this unyielding expression of revolutionary nationalism meant that Mexico’s right to self-determination was inviolable.

After the United States’ entry into the war in 1917, its government intensified the Pan Americanist campaign to align Latin America behind its foreign policy. The Argentine President, Hipólito Yrigoyen (1852-1933), promoted a common strategy of the Latin American neutrals, inspired by Pan Hispanism, to counteract the dissemination of Pan Americanism in the subcontinent. However, in the following months most of them severed diplomatic relations with Germany and even a few declared war against it. Only Argentina, Chile, Paraguay, Mexico, Colombia, El Salvador and Venezuela remained neutral until the end of the conflict.

Wilson used Colonel House’s ideas in the Fourteen Points and invoked them at the Paris Peace Conference in his advocacy of collective security. They became crucial ingredients in the Treaty of Versailles and critical points of contention in the ensuing treaty fight at home.

Economic Consequences↑

In contrast, economic policies were quite successful. Because of German submarine warfare and the British blockade, Latin Americans as suppliers of raw materials lost access to European markets. Moreover, because of wartime priorities and huge expenditures, Europeans could no longer function as suppliers of finished goods and investment capital. As a consequence and with little choice, Latin Americans turned to the United States. The Wilson administration responded enthusiastically. The U.S. became the prime purchaser of raw materials and the main seller of finished goods. During the period between 1 July 1914 and 30 June 1917, trade increased by more than 100 percent.

Seeking to capitalize on these opportunities, the Wilson administration sponsored various promotional activities. In September 1914, the State Department and the Commerce Department sponsored a Latin American Trade Conference in support of commercial expansion. Meanwhile, groups such as the Chamber of Commerce, the Southern Commercial Congress, and the National Foreign Trade Council urged the importance of improved transportation and banking, as well as better sales techniques, conforming more closely to Latin American tastes and preferences. Other examples included a Pan American Financial Conference in Washington in May 1915 and a Pan American Scientific Conference in January 1916, followed by other innovation. By such means, the United States displaced Great Britain as Latin America’s leading foreign investor and trading partner. This part of Wilson’s policy worked well and set the stage for intense economic competition with the British after the war.

Mark T. Gilderhus, Texas Christian University

Section Editor: Frederik Schulze

Selected Bibliography

- Albert, Bill: South America and the First World War. The impact of the war on Brazil, Argentina, Peru, and Chile, Cambridge; New York 1988: Cambridge University Press.

- Compagnon, Olivier: Entrer en guerre? Neutralité et engagement de l’Amérique latine entre 1914 et 1918, in: Relations internationales 137/1, 2009, pp. 31-41.

- Gilderhus, Mark T.: Pan American visions. Woodrow Wilson in the Western Hemisphere, 1913-1921, Tucson 1986: University of Arizona Press.

- Gilderhus, Mark T.: The second century. U.S.-Latin American relations since 1889, Wilmington 2000: Scholarly Resources.

- Whitaker, Arthur Preston: The Western Hemisphere idea. Its rise and decline, Ithaca 1954: Cornell University Press.