Early Life↑

Henry Morgenthau Senior (1856-1946) was born to a German cigar manufacturer of Ashkenazi Jewish descent, who immigrated to New York City in 1866 after the collapse of the family’s fortunes. After graduating from Columbia Law School, Morgenthau became wealthy through his legal practice and real estate investments. On account of his successful adaptation to his adopted country, Morgenthau became an outspoken Assimilationist, rejecting the premise of political and territorial autonomy demanded by Zionists.[1] Morgenthau used his wealth to fund Jewish community projects and Democratic political candidates, leading to a close connection with presidential candidate Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924).[2] After his election in 1912, Wilson offered the ambassadorship to the Ottoman Empire to Morgenthau, thus following the practice of appointing a Jewish person to foster good relations between the Ottoman administration and its Christian and Jewish minorities. Morgenthau was insulted by the offer, principally due to its implied premise of the divided loyalties of Jews.[3] Morgenthau accepted only after Wilson pointed out how the post in Constantinople: “…was the point at which the interest of American Jews in the welfare of the Jews of Palestine is focused, and it is almost indispensable that I have a Jew at that post.”[4]

Diplomatic Service in the Ottoman Empire↑

Henry Morgenthau assumed duties as ambassador in November 1913, where he devoted his time to “encouraging the work of Christian missionaries and spreading the gospel of Americanism.”[5] The United States remained neutral after the start of the First World War. However, Morgenthau took on the additional role of protecting the diplomatic interests, property, and expatriates from France and Britain.[6]

Armenian Genocide↑

In early 1915, Morgenthau first learned of the liquidation of Armenian men from reports of American consular officials. Morgenthau’s efforts to confirm the reports were brushed off by the Minister of Interior Mehmet Talat Pasha (1874-1921) and Minister of War Ismail Enver Pasha (1881-1922), leading members of the Young Turk Committee of Union and Progress (CUP). Morgenthau was convinced of CUP plans to massacre the Armenians after the 24 April 1915 mass arrest of prominent Armenian leaders in Constantinople.[7] Subsequent reports from American eyewitnesses detailed how Turkish gendarmes and soldiers systematically ordered Armenian women and children from their Anatolia homeland on forced marches towards the Syrian Desert.[8] On the march, the Armenian deportees were systematically brutalized, and most were murdered by detachments of the çetes (Special Organization), a CUP organized militia. Surviving Armenians were herded into concentration camps, where they were vulnerable to disease, starvation, and further abuse. Of the estimated 1.5 million Armenians living in Anatolia in August 1914, over 1 million had been deported from the Ottoman Empire by 1917.[9]

Ambassador Morgenthau’s Response↑

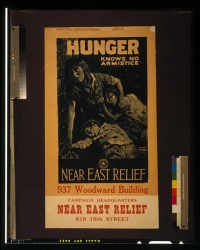

When Morgenthau returned to confront Enver and Talaat on the reports, he was told the Ottoman operations were in revenge for Armenian collaboration with the Russian army. Morgenthau was similarly rebuffed by the German ambassador, who cited the deportations as militarily justified. In an attempt to influence U.S. policy towards the Ottoman Empire, Morgenthau collected and forwarded the eyewitness accounts to the U.S. State Department.[10] Determined to remain neutral, the Wilson government remained officially noncommittal, while allowing major newspapers to reproduce Morgenthau’s reports to generate public sympathy. A group of Morgenthau’s colleagues established the American Committee for Syrian and Armenian Relief in 1915, part of a larger outpouring of aid for Armenian refugees. Largely helpless to prevent the deportation and massacre of Armenians inside the Ottoman Empire, Morgenthau was credited with mobilizing aid which markedly lessened the suffering of the surviving Armenian refugees.[11]

Post-Ambassadorship↑

Heartsick at his apparent lack of success, Morgenthau resigned his post in January 1916 and returned home to New York City. Morgenthau retained Wilson’s trust and in mid-1917 Morgenthau returned to the Ottoman Empire in an unsuccessful bid to convince the Ottomans to conclude a separate peace. After the end of the war, Morgenthau headed a board of inquiry sent to Poland to investigate allegations of Polish-abetted pogroms. The entire process was marred by controversy, as Zionists decried Morgenthau’s appointment and resented his criticism of their exaggerations of Polish wrongdoing, while the Polish government was alarmed (and the American State Department embarrassed) by Morgenthau’s even-handed criticism of Polish neglect of Jewish security needs.[12] Morgenthau’s antipathy towards Zionism prompted his signing of an anti-Zionist petition handed to President Wilson before his departure to the Paris Peace Conference.[13] Morgenthau also attended the Paris Conference as a diplomatic advisor regarding Eastern Europe and Middle Eastern affairs. Later, Morgenthau served on Armenian and Greek Refugee Settlement commissions. He died at New York City in 1946. [14]

Ambassador Morgenthau’s Story↑

Ambassador Morgenthau’s Story was published in December 1918, which detailed Morgenthau’s attempts to ameliorate the plight of the Armenians.[15] From the time of its release to the modern era, Morgenthau’s Story profoundly shaped popular memory of the Armenian deportations.[16] The accuracy of the book has been challenged by scholars within and outside the Turkish government for distorting Morgenthau’s conversations with Taalat and Enver.[17] In particular, Heath W. Lowry’s 1990 work, The Story Behind Ambassador Morgenthau’s Story, challenged the accuracy of key passages in Morgenthau’s Story by comparison to Morgenthau’s own diary entries.[18]

Harold Allen Skinner Jr., United States Army Soldier Support Institute

Section Editor: Pınar Üre

Notes

- ↑ Tuchman, Barbara: The Assimilationist’s Dilemma: Ambassador Morgenthau’s Story, issued by: Commentary Magazine, May 1977, online: https://www.commentarymagazine.com/articles/barbara-tuchman/the-assimilationist-dilemma-ambassador-morgenthaus-story/ (retrieved: 6 March 2020).

- ↑ Morgenthau, Henry and Strother, French: All in a Lifetime, New York 1922, pp. 160-1.

- ↑ Tuchman, The Assimilationist’s Dilemma 1977.

- ↑ Oren, Michael B.: Power, Faith and Fantasy: America in the Middle East 1776 to the Present, New York 2008, p. 333.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 204.

- ↑ Morgenthau, Henry: Secrets of the Bosphorus, London 1918, pp. 85-6.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 215-216.

- ↑ Astourian, Stephen et al.: Remembrance and Denial: The Case of the Armenian Genocide, Detroit 1998, p. 91.

- ↑ Sarafian, Ara: Talaat Pasha’s Report on the Armenian Genocide. London 2011, p. 6.

- ↑ Suny, Ronald G.: “They Can Live in the Desert but Nowhere Else”: A History of the Armenian Genocide, Princeton 2017, p. 311.

- ↑ Janbazian, Rupen: The U.S. and the Armenian Genocide: Humanitarianism, Politics and the Struggle for Recognition, issued by: Armenian Weekly, 17 October 2014, online: https://armenianweekly.com/2014/10/17/us-armenian-genocide/ (retrieved 24 November 2019). History, issued by: Near East Foundation, online: https://www.neareast.org/who-we-are/ (retrieved 25 November 2019).

- ↑ Wandcycz, Piotr S.: Ideology, Politics and Diplomacy in East Central Europe. Rochester 2003, pp. 69-74.

- ↑ Corrigan, Edward C.: Jewish Criticism of Zionism, in: Journal of the Middle East Policy Council (Winter 1990-91), p. 35.

- ↑ Biographical sketch, issued by: U.S. Library of Congress, undated, online: https://www.loc.gov/item/mm78033498/ (retrieved 6 March 2020).

- ↑ Morgenthau, Henry: Ambassador Morgenthau’s Story, New York 1918, introduction.

- ↑ See for example, Melson, Robert: Revolution and Genocide: On the Origins of the Armenian Genocide and the Holocaust, Chicago 1997, p. 311.

- ↑ See for example, the official Turkish Government’s webpage addressing “The Armenian Allegation of Genocide,” issued by: The Republic of Turkey Ministry of Foreign Affairs, online: http://www.mfa.gov.tr/the-armenian-allegation-of-genocide-the-issue-and-the-facts.en.mfa (retrieved 26 November 2019).

- ↑ For analysis of Lowry’s work and conclusions, see Michael M. Gunter’s book review of The Story behind Ambassador Morgenthau’s Story, Turkish Studies Association Bulletin 15/1 (March 1991), pp. 168-170.

Selected Bibliography

- Akçam, Taner: The Young Turks' crime against humanity. The Armenian genocide and ethnic cleansing in the Ottoman Empire, Princeton 2012: Princeton University Press.

- Balakian, Peter: The burning Tigris. The Armenian genocide and America's response, New York 2003: HarperCollins.

- Lowry, Heath W.: The story behind Ambassador Morgenthau's story, Istanbul 1990: Isis Press.

- Morgenthau, Henry: Ambassador Morgenthau's story, Garden City 1918: Doubleday, Page & Company.

- Morgenthau, Henry / Strother, French: All in a life-time, Garden City 1922: Doubleday, Page and Company.

- Sarafian, Ara: Talaat Pasha's report on the Armenian Genocide, 1917, London 2011: Taderon Press.

- Suny, Ronald Grigor: 'They can live in the desert but nowhere else'. A history of the Armenian Genocide, Princeton 2015: Princeton University Press.