Introduction↑

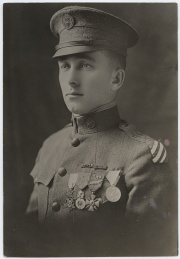

Private John Lewis Barkley (1895-1966) received the Congressional Medal of Honor for singlehandedly breaking up a German counterattack during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive in 1918. Although this feat of arms rivaled that of Sergeant Alvin York (1887-1964), the most celebrated American hero of the First World War, Barkley spent most of his life in relative obscurity. Only recently has his story become better known, thanks to the reissue by the University Press of Kansas of Barkley’s combat memoir, which originally appeared in 1930 under the title No Hard Feelings! and met with disappointing sales and reviews.

Pre-war Life↑

A descendent of Daniel Boone (1734-1830) (according to his memoir), Barkley grew up on a farm near Holden, Missouri, and excelled at fishing, hunting, and trapping. He would later claim that his early experiences in the outdoors saved his life on the Western Front. From a young age, he was an exceptional shot with a rifle and an expert tracker, skills that served him well on the battlefield. After graduating from Holden High School, Barkley attended nearby Warrensburg Teachers College (now the University of Central Missouri).

Service in the First World War↑

When the United States entered the war in April, 1917, Barkley left college and attempted to enlist, but was rejected because of his stutter. Months later, draft notice in hand, he tried again, this time successfully. Barkley’s background made him a perfect choice for intelligence (what we would today call “reconnaissance”) training, and he received special instruction as a sniper, observer, and scout at Fort Riley, Kansas. Assigned to Company K of the 4th Infantry Regiment, 3rd Division, Barkley arrived in France in the spring of 1918. During combat operations, he served in an intelligence platoon at the battalion level, where his closest comrades included two Native Americans, Jesse James and William Floyd, both experienced professional soldiers.

Barkley saw action in every major battle fought by the 3rd Division, one of the AEF’s most bloodied units, including the Second Battle of the Marne and the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, where he earned the United States’ highest decoration for valor. On the afternoon of 7 October 1918, while occupying a lookout post in front of the American lines, he noticed a German force massing at the edge of some woods near the town of Cunel. Realizing that an enemy counterattack was about to begin, Barkley seized a German light machine gun, along with as much ammunition as he could carry, and took up position in an abandoned two-man Renault tank whose cannon had been removed, leaving a large hole in the turret. Barkley aimed his machine gun through this aperture, waited for the enemy to cross the field in front of him, and then opened fire. Over the next hour or so, he held off two German assaults and probably killed more than a hundred enemy soldiers. Barkley later claimed that he was taken totally by surprise when, weeks later, fellow Missourian General John J. Pershing (1860-1948) pinned the Medal of Honor to his chest.

Post-war Years↑

Restlessness characterized Barkley’s life immediately following the war. Perhaps hoping to recapture the intensity of life at the front lines, he worked for a time as a private detective in Kansas City, Missouri. But his love of the outdoors soon pulled him back to the countryside. As agricultural prices plummeted, he struggled to keep the Barkley family farm afloat and to support his widowed mother. In 1930, desperate for additional revenue, he placed a ghostwritten memoir of his war experience with a New York publisher. Titled No Hard Feelings!, the book flopped. The boom in war narratives, triggered by the spectacular success of Erich Maria Remarque's (1898-1970) All Quiet on the Western Front (1929), had already come and gone, and many reviewers, expecting another anti-heroic denunciation of modern warfare, were put off by the apparent zest with which Barkley described combat. The onset of the Great Depression did not help matters. The one and only print run of No Hard Feelings! numbered fewer than 4,000 copies.[1]

Barkley’s financial situation ultimately improved, and toward the end of his life, he helped establish public parks in suburban Johnson County, Kansas (part of the greater Kansas City area). He was also an active supporter of the Liberty Memorial, a gigantic commemorative complex (today home to the National World War I Museum) that honors the more than 400 citizens of Kansas City who died in the Great War. In 2012, the University Press of Kansas reissued No Hard Feelings! under the title that Barkley originally preferred—Scarlet Fields.

Steven Trout, University of South Alabama

Reviewed by external referees on behalf of the General Editors

Notes

- ↑ Trout, Steven: Introduction to Scarlet Fields. The Combat Memoir of a World War I Medal of Honor Hero, Lawrence 2012, p. 17.

Selected Bibliography

- Barkley, John Lewis: Scarlet fields. The combat memoir of a World War I medal of honor hero, Lawrence 2014: University Press of Kansas.

- Lengel, Edward G.: To conquer hell. The Meuse-Argonne, 1918. The epic battle that ended the First World War, New York 2009: Henry Holt and Co.

- United States Army, 3rd Division (ed.): History of the Third Division United States Army in the World War for the period December 1, 1917 to January 1, 1919, Cologne 1919.