Introduction↑

The aim of this article is to examine the ways in which British and Irish women mobilized for the First World War. Historians have long debated the relationship between total war and women’s lives. Do the demands of the wartime state for labour provide new opportunities for women? If so, are these opportunities maintained or reversed at the war’s end? In short, does war liberate women?

So wrote the young Vera Brittain (1893-1970), feminist author and one of the best-known peace activists of the 20th century, on the eve of war in August 1914. As Brittain is (justly) best known for her opposition to war, and her role as eulogist of the "lost generation" of 1914-18, it is instructive to recall that her initial response to the outbreak of war in 1914 was one of excitement and anticipation, rather than fear and anxiety. Yet perhaps this should not surprise us. Brittain was an upper-middle class young woman, privileged in more ways than one (she was about to take up a place at Somerville College Oxford to read English), but nonetheless frustrated by the social and cultural rules that governed women’s lives in Edwardian Britain. Class bound and highly gendered in its social make up, Edwardian Britain was a long way from the "innocently but irrecoverably lost" idyll that Paul Fussell (1924-2012) memorably punctured in The Great War and Modern Memory.[2] Women’s lives were limited not only by the political constraints inherent in a system that still refused to enfranchise them, but also by a range of economic, social and cultural limitations that ensured that while middle class women’s access to a public life had changed little since the late 19th century, working class women continued to negotiate the contradictions of a society that demanded that they be educated for motherhood and domesticity while the economic system in place ensured that they were often employed in poorly paid and low status occupations. No wonder then that the promise of disruption that the outbreak of war offered provoked excitement rather than dismay in the young Vera Brittain.

War and Women’s Liberation: An Overview↑

The outbreak of the First World War can, in some significant ways, be seen as limiting and containing the feminist challenges to Edwardian society. The Suffrage movement was divided on the outbreak of war. The Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), the militant suffragette organisation, abandoned the campaign of direct action it had been running since 1912 in order to support the war effort. Changing the name of its publication The Suffragette to Britannia, the WSPU ran regular recruitment rallies and pageants which drew on the pre-war campaign’s sense of theatre and use of symbolism to act as both an effective recruitment tool and to highlight a particularly female form of patriotism, with slogans such as "Shells made by a wife may save a husband’s life." The suffrage colours of green, purple and white were replaced with the red, white and blue of the Union flag.[3]

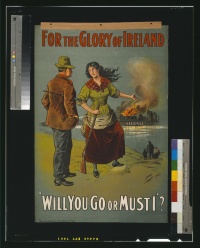

Not all members of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), however, threw themselves into the war effort with such enthusiasm. Sylvia Pankhurst (1882-1960), Emmeline Pankhurst’s (1858-1928) socialist and suffragist daughter, working and living in the East End of London, was horrified by her mother and sister Christabel Pankhurst’s (1880-1958) support for the war. She chose instead to work to alleviate the poverty amongst women in the East End who had lost their jobs when the middle classes "patriotically" stopped buying goods such as hats and haberdashery, made in the sweatshops of the area. The NUWSS, which had opposed the war up until its outbreak, split between the majority, led by the organisation’s founder Millicent Fawcett (1847-1929), who argued that the war was being fought for the very principles of democracy that they had campaigned for, and the pacifist minority who believed the bonds of international sisterhood overrode national concerns. When the International Congress of Women convened a Peace Conference at The Hague in 1915, several members of the NUWSS executive resigned, joining other pacifist and internationalist women to form the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. In Ireland, female opposition to the war was often linked with the nationalist cause. The feminist and anti-militarist Hannah Sheehy-Skeffington (1877-1946) was banned from attending the Conference at The Hague in 1915, but continued campaigning against both war and British imperialism. Cumann na mBan (The Irishwomen’s Council) like the British feminist organisations, split on the outbreak of war, with some members supporting John Redmond (1856-1918) and the National Volunteers whilst others agreed that "England’s difficulty is Ireland’s opportunity" and used the opportunity the war offered to organise for Irish independence. Members of the organisation participated in the Easter Rising in 1916 and Countess Constance Markievicz (1868-1927), a member of James Connolly’s (1868-1916) socialist Irish Citizen Army, was court martialled and sentenced to death for her part in the fighting, a sentence later commuted to imprisonment.

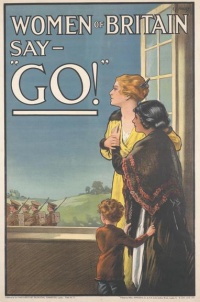

For the majority in the suffrage movement, however, British war aims were entwined with the rights of women. The war provided an opportunity for women to prove that they were every bit as patriotic as men, and just as ready to serve their country, and thus just as deserving of the full rights of citizenship. A range of women’s voluntary organisations were established in the early days of the war, many of them co-ordinated by the Women’s Emergency Corps (WEC), organised by the NUWSS, which bought its formidable powers of organisation to bear on the management of a range of different activities. It ran a clearing house in London that aimed to send volunteers where they were most needed. One poster for the WEC, titled "The Call of the Country" mirrored Horatio Herbert Kitchener’s (1850-1916) recruiting poster for men in its claim that "Women! Your Country Needs You!". Urging women to "give of your best in the same spirit in which your brothers have answered the Nation’s call" the WEC used a militarised language to place women’s work in wartime alongside that of men’s, claiming, in common with the wartime WSPU a particularly feminine patriotism.

While the main suffrage organisations abandoned direct political campaigns during the war years, focusing instead on women’s wartime work, gender equality was about much more than voting rights. Consideration of the impact of war on women’s lives has been a central aspect of what became known as "the modernisation thesis": the argument that the massive challenges and disruptions of total war help to modernise society; to drive forward social, cultural, political and economic change at a faster pace than would be the case in peacetime. Proponents of this argument, such as the social historian Arthur Marwick, have pointed to changes such as the (limited) enfranchisement of British women in 1918, the movement of women into new areas of work and the emergence of the sexually liberated "flapper" in the 1920s as evidence of war’s ability to greatly accelerate existing social trends.[4] The war years have also been understood as a time when women’s lives changed in other, less quantifiable ways. War work often provided women with increased independence, as it took young women away from the parental home for the first time. Female fashions changed as the practical needs of war work, together with fabric shortages, replaced Edwardian frills and flounces with shorter skirts and trousers. Most difficult to assess, but often vividly present in many of the diaries, autobiographies and spoken memories of women who lived through the war is the increased confidence that came from feeling oneself and one’s work to be a valued part of the collective war effort.

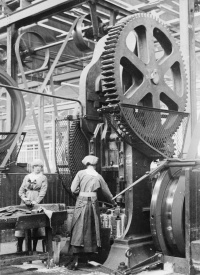

However, the growth of feminist history since the late 1960s has seen the development of a convincing critique of this thesis. Gail Braybon pointed to a process of "dilution", by which women were employed to replace men, to argue that any changes to women’s work practices brought about by the demands of war for labour were strictly limited and circumscribed, "for the duration only".[5] The 1915 Treasury Agreement between the government and thirty-five trades unions allowed women and boys into areas of employment such as engineering on the understanding that they were only trained to do part of a skilled man’s job, ensuring they remained unskilled or semi-skilled workers, on commensurately lower rates of pay. The Amalgamated Engineering Union, the main engineering union, also negotiated a separate category of membership for women that ensured their employment would conclude at the war’s end. The employment of women in some occupations saw men withdrawing their labour in protest, such as the "serious dispute" reported in Croydon in 1917 when "two women were being taught to drive tramcars, resulting in a cessation from work for many weeks", followed by a case where "upon women being appointed as mail drivers the men ceased work immediately, and as a result the women have since been withdrawn."[6] Overwhelmingly the Unions, and many individual male workers, saw the employment of women in areas that had previously been the preserve of men as a threat to both their status and their pay, and rather than campaigning for women’s pay and training to match that of men, they urged dilution, lower rates of pay and temporary contracts on employers in an attempt to ensure that hard-won working conditions and pay rates would be in place for men when they returned from the war.

The turn towards cultural history, and towards an examination of gender rather than of women’s experiences, in the 1980s saw the emergence of a third influential paradigm for understanding the relationship between war and gender. Margaret and Patrice Higonnet used the metaphor of the "Double Helix" to argue that, whilst women undoubtedly took a step forward in wartime, moving into occupations that had previously been understood as male, this was only because the men themselves had taken a simultaneous step forward, into the highly dangerous but high status roles of wartime combatants, roles that remained the preserve of men. When these men returned from war, women returned to their pre-war roles and occupations. Thus, although women undertook new jobs in wartime, moving into areas of industrial, transport and even military occupations that had been closed to them in peacetime, the relationship between the genders – between masculinity and femininity – remained the same. Through an analysis of discourse, rather than experience, the Higonnets argued that because the "dynamic of gender subordination" remained the same in wartime as it was in peacetime, the mobilisation of women for war did little to upset traditional gender boundaries and relations.[7]

Women in Uniform↑

For some women, however, the changes of wartime were not easily undone; the new opportunities and experiences had a profound impact on both their sense of self, and their sense of what women were capable of, that continued long after the war years. Perhaps two groups of women whose lives were particularly changed by their wartime work were women in the auxiliary services, and women nurses. Both wore uniform, both worked closely with the military, and were often close to the "battle front", and both saw a side of the wartime experience that was largely hidden from those who were employed at a greater distance from the front-line, and the men who fought and died there.

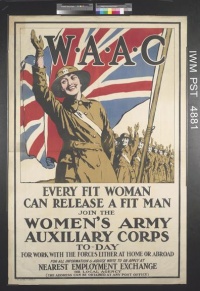

In 1916 the British government began to consider employing women as auxiliary workers with the army, a decision driven by the high casualty rates on the Western Front, and the concurrent need to comb out men from military work "behind the lines" for front-line combat. Women’s volunteer services, such as the Women’s Legion and the Women’s Volunteer Reserve had long been lobbying for a role for women in the military, and as early as 1914 rumours circulated in the British press of a "battalion of suffragettes" who had travelled to the front lines, determined to fight. Unfounded though these were, a sizeable number of women were keen to don a military uniform and play a more "active" role in the war effort. By the war’s end, women were serving not just with the army, but also with the Royal Navy and with the recently created Royal Air Force, both of which formed auxiliary female branches in 1918.

In 1917 the War Office announced the creation of the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC), formed to support men in the army, and to replace men behind the lines by employing women as clerks, drivers, cooks and canteen workers, domestic staff and, most poignantly, as tenders of war graves. Although the nature of their employment was, in some ways, revolutionary, as they wore official army uniforms and worked alongside men, in other ways it reinforced the existing gendered division of work. As in the factories, dilution was used. More women were employed than men to do the same jobs: so if three male clerks were "combed out" for combat work, they would be replaced by four women, and three male mechanics would be replaced by four female mechanics, all of whom were paid lower wages than the men they were replacing. Women were positioned firmly behind men, their supportive, non-combatant role ensuring that gender roles, and the status of the combatant man, were maintained.

The majority of recruits to the WAAC were young working class women, often attracted by the higher wages the service offered. In the public mind however, they were sometimes perceived as thrill seekers, drawn by a desire for adventure and romance, and recruitment to the service suffered from fears that women were finding opportunities for sexual liaisons with the soldiers. So worried was the government by these rumours that a Commission of Enquiry was formed, which included figures showing the number of pregnancies amongst unmarried members of the WAAC was lower than among unmarried civilians, although these findings were overshadowed by the rapid German advance just before Easter 1918. This military setback however, did more to improve the standing of the WAAC than any report: when eight members of the Corps were killed in a bombing raid on their camp at Etaples, France, they were buried with full military honours, represented as martyrs in the press, and the name of the Corps was changed to the Queen Mary Army Auxiliary Corps, in recognition of the service and sacrifice of the women.

Women in the nursing services, particularly those in the Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) and the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry (FANY), faced less prejudice than women in the auxiliary military organisations. Protected in part by their social class, as these organisations largely recruited women from the upper and upper middle classes, and in part by their more traditionally feminine role of caring for the soldiers, 90,000 British and Irish women were registered as VADs by 1918, while approximately 450 members of the FANY served on the Western Front, as nurses, drivers and mechanics.

Both the VAD and the FANY were formed before 1914, and can be understood as part of a wider move towards a militarised society in pre-war Britain. In 1907 Richard Burdon Haldane (1856-1928), Secretary of State for War, made sweeping reforms of the armed services, creating a new Territorial Force of reserve soldiers. The VAD were established in 1909 as part of this move towards the creation of reserve forces in Britain, and both male and female detachments were set up to fill gaps in the Territorial Medical Services. By 1914, over 1,700 female detachments had been registered with the Home Office. Under the aegis of the Red Cross, the VADs were initially only expected to undertake "home" service, working in Britain or Ireland, but a shortage of trained nurses opened the door for VADs in overseas hospitals, and in 1915 female volunteers over the age of twenty-three with at least three months hospital experience were accepted for overseas service. VADs, under the leadership of trained military nurses, undertook a wide range of hospital duties, some of which must have been shocking to inexperienced young women. Cleaning, assisting at operations, changing dressings and tending to the dying, the work was both physically and emotionally demanding and far from the romantic and patriotic ideals that had led so many to volunteer. Mrs D. M. Richards, who worked as a VAD in Britain, described her first experience of changing a difficult dressing:

For some, the strains and demands of the work became too much and convalescent homes were established for nurses behind the front lines in France. Alice Essington-Nelson, who helped to run one of these homes, described women who "have their nerves shattered, one of these latter, when she came just cried if you spoke to her ... she told me what had finished her was the night after the battle of Neuve Chappelle, when 45 terrible cases had come into her bit of the ward, and 15 had died before morning."[9] Some nurses suffered from long periods of ill health as a result of the demands of their work, whilst others died, of infection, of illness, of wounds after hospital camps were bombed, and by drowning, when ships carrying nurses and soldiers overseas were torpedoed. According to the Commonwealth War Graves Database, seventy-five VADs, in addition to numerous other civilians who volunteered in a range of capacities, were victims of the war, dying as a result of enemy action, accident or illness contracted while serving.[10] Whilst nurses undoubtedly did often provide comfort and solace to the dying and injured men that they tended, their experience of work, tending to the victims of often heavily industrialised warfare, was a long way from the romantic "angel of mercy" ideal of battlefield nursing that had dominated in the pre-war period.

The FANY, the other main voluntary nursing organisation, had an experience of the war that was quite different to that of the VAD. Formed in 1907, the Yeomanry was initially imagined as a Corps of mounted nurses who would ride onto the battlefield to tend to wounded soldiers. Members were expected to own their own horse, and to provide their own uniform and nursing materials. Combining the appeal of adventure with the acceptable feminine ethos of nursing and caring for men in wartime, with the substantial membership fee of ten shillings, plus six shillings a month riding school subscription, the FANY appealed primarily to the daughters of the upper classes. On the outbreak of war the FANY, unlike the VAD, which came under the overall command of the War Office, struggled to find a role for itself. Grace Ashley Smith (1889-1963), by then in command of the Corps, travelled independently to Antwerp to offer the yeomanry’s services to the Belgian government. Working initially in Belgium and later in Northern France, the FANY ran hospitals and casualty stations. Replacing their horses with ambulances and cars, they transported the wounded from the front lines to base hospitals, eventually being commissioned by the Red Cross to convey wounded men to Calais. Their autonomous standing meant that, at the war’s end, they were not disbanded but continued as a socially elite volunteer organisation, moving away from their more military activities, instead taking up philanthropic and charitable work, before eventually being partially absorbed into the Auxiliary Territorial Service during the Second World War.

Conclusion: Gender Roles - Challenges and Changes↑

In the aftermath of the Armistice, the majority of women unsurprisingly left their wartime employment. The auxiliary services all closed down, armaments factories, of which the largest, Woolwich Arsenal, had employed 25,000 women in 1918, wound down production, and women in other occupations found themselves pushed out to enable returning soldiers to find employment. As the numbers of women registered as unemployed soared during the post-war slump, the government introduced regulations that denied unemployment benefit to any woman who turned down work in domestic service. Domestic service, which had employed almost 1,500,000 women before the war, was an unpopular form of employment among young working class women, offering lower rates of pay, little free time and a greater degree of surveillance than factory work. Yet it was still seen as being naturally suited to women, and a variety of schemes were created to try and ensure that there would be an adequate supply of domestic servants in the post-war years.[11] In an attempt to make this unpopular form of employment more appealing Edith Helen Vane-Tempest-Stewart, Marchioness of Londonderry (1878-1959), who had formed the Women’s Legion during the war, set up a Women’s Legion Household Service in 1919, an organisation that was meant to professionalise domestic service by restructuring it along the lines of the wartime auxiliary services, providing members with training, a badge of membership and a minimum wage. Doomed by the reluctance of employers to accept a minimum wage and the continued reluctance of many women to enter domestic service, the scheme had disappeared without trace by the early 1920s.[12]

The drive to get women back into traditional areas of employment, and into domesticity, was matched by a backlash against female war workers in the popular press. Women who had worked in the war industries were portrayed as "ruthless self seekers, depriving men and their dependents of a livelihood".[13] The author Caroline Gascoigne Hartley (1867-1928), warned that the social changes brought about by the war, and women’s increased financial and social independence, would lead to moral decline as women would "seek to get presents from men", leading to "prostitution" as "the weaker sort of girl will desire to sell her body rather than return to the humdrum of drudgery in back kitchens."[14] Public perceptions of women’s contribution to the war effort had undertone a transformation since 1915 when Edith Cavell (1865-1915), the British nurse executed for helping British servicemen escape from German captivity in Belgium, was widely seen as an embodiment of patriotic, brave and selfless British womanhood. Like the returning servicemen, transformed by rising unemployment and inadequate pensions from heroes to potential revolutionaries, the female workers of the war years were seen as posing a threat to the post-war status quo. In Ireland, where the nationalist women’s organisation, Cumann na mBan, played an important role in the War of Independence, militant female dissidence was a particular problem for the state.

Despite the extension of the franchise to approximately 8.4 million women over thirty years of age in 1918, the war failed, overall, to bring about the liberation of British women. While the interwar years saw a gradual expansion in women’s employment they remained marginal to high status occupations: in the early 1930s there were only 2,810 female doctors and 195 female lawyers in Britain, and the majority of professions and many employers continued to operate marriage bars, meaning women had to leave employment upon marrying.[15] While 34 percent of British women worked outside the home by 1931, the majority remained in low paid, low status, "women’s work", which was often seen as a transition period between the end of education and marriage.[16] Although many women experienced their wartime jobs as a moment of liberation, any consideration of the impact of the war on work opportunities for women would have to conclude that the post-war backlash against working women, combined with the constraints placed on women’s work during the war, ensured that any changes were short term, largely "for the duration" and coming to a close with the end of the war. It was to take another war before the changes in women’s working lives, driven by the needs of wartime, were to become a more permanent feature of British society.

Lucy Noakes, University of Brighton

Section Editor: Edward Madigan

Notes

- ↑ Bishop, Alan (ed): Chronicle of Youth. Vera Brittain’s War Diary 1913-1917, London 1981, p. 84.

- ↑ Fussell, Paul: The Great War and Modern Memory, Oxford 1975, p.24.

- ↑ The Times, 7 July 1915.

- ↑ Marwick, Arthur: The Deluge. British Society and the First World War, Harmondsworth 1965.

- ↑ Braybon, Gail: Women Workers in the First World War. The British Experience, London 1981.

- ↑ The National Archives, London: Letter from the President of the London and Provincial Union of Licensed Vehicle Workers to the Home Secretary, 13 February 1917, catalogue reference HO 45/11164.

- ↑ Higonnet, Margaret and Higonnet, Patrice: ‘The Double Helix’. In Margaret Higonnet, Jane Jenon, Sonya Michel & Margaret Collins Weitz (eds): Behind the Lines. Gender and the Two World Wars, New Haven 1987.

- ↑ Cited in Hallett, Christine E.: Containing Trauma. Nursing Work in the First World War, Manchester 2011, p. 216.

- ↑ Cited in Hallett, Containing Trauma 2011, p. 215.

- ↑ http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead.aspx?cpage. Retrieved 30 January 2014. This information can be accessed via the Commonwealth War Graves Commission search engine by searching for miscellaneous casualties recorded from the First World War.

- ↑ Todd, Selina: Domestic Service and Class Relations in Britain 1900-1950 in: Past and Present 203:1 (2009), pp. 181-204.

- ↑ Noakes, Lucy: Demobilising the Military Woman: Constructions of Class and Gender in Britain after the First World War in: Gender and History 19:1 (2007), pp.143-162.

- ↑ Clapham, Irene: Towards Sex Freedom, London 1935, p.201.

- ↑ Gascoigne-Hartley, Caroline: Women’s Wild Oats: Essays on the Re-fixing of Moral Standards, London 1919, p. 47.

- ↑ Pugh, Martin: Women and the Women’s Movement, Basingstoke 2000, p.92.

- ↑ Halsey, Albert Henry (ed): British Social Trends Since 1900: A Guide to the Changing Social Structure of Britain, London, 1988, p.106.

Selected Bibliography

- Bishop, Alan (ed.) / Brittain, Vera: Chronicle of youth. War diary, 1913-17, London 1981: Gollancz

- Braybon, Gail: Women workers in the First World War (2 ed.), London; New York 1990: Routledge.

- Braybon, Gail / Summerfield, Penny: Out of the cage. Women's experiences in two world wars, New York 1987: Routledge & K. Paul.

- Fussell, Paul: The Great War and modern memory, Oxford 2013: Oxford University Press.

- Gullace, Nicoletta F.: 'The blood of our sons'. Men, women, and the renegotiation of British citizenship during the Great War, New York 2002: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hallett, Christine E.: Containing trauma. Nursing work in the First World War, Manchester 2009: Manchester University Press.

- Higonnet, Margaret R. / Jenson, Jane (eds.): Behind the lines. Gender and the two world wars, New Haven; London 1987: Yale University Press.

- Marwick, Arthur: The deluge. British society and the First World War, Boston 1966: Little, Brown.

- Noakes, Lucy: Women in the British Army. War and the gentle sex, 1907-1948, London; New York 2006: Routledge.

- Pašeta, Senia: Irish nationalist women, 1900-1918, Cambridge 2013: Cambridge University Press.

- Pickles, Katie: Transnational outrage. The death and commemoration of Edith Cavell (2 ed.), Houndmills; New York 2015: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Pugh, Martin: Women and the women's movement in Britain 1914-99, Basingstoke 2000: Macmillan.

- Thom, Deborah: Nice girls and rude girls. Women workers in World War I, London; New York 1998: I. B. Tauris.

- Woollacott, Angela: On her their lives depend. Munitions workers in the Great War, Berkeley 1994: University of California Press.