Introduction↑

The conflict in South East Europe (the Balkans and Romania) has been overshadowed by the other theaters of the Great War and does not, perhaps, attract the attention of historians and other experts that it deserves. Taking into consideration the millions of people who fought and died in the great battles on both the Western and Eastern fronts, this is of course understandable. However, the battlefields of South East Europe played an important role in the development of European history and should not be neglected.

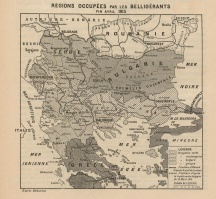

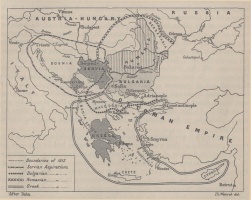

The Great War originated in the Balkans. The first battle, and with it, the first Allied victory took place in mid-August 1914 on the Serbian front. Finally, the last armistice of the Great War was signed with Hungary in Belgrade on 13 November 1918.[1] However, the events of the First World War in South East Europe actually represent a war within a war, or an extension of the Balkan wars (1912-1913). The outbreak of the Great War provided an excellent opportunity for the revision of previous peace accords in the Balkans.[2] The belligerent Great Powers exploited Balkan tensions and rivalries to their own ends in the search for useful alliances. Austria-Hungary sought to annex Serbia, whose independence represented a serious threat to the future of the dual monarchy. Russia, on the other hand, was focused on the Straits and Constantinople. For Germany, Britain and France the region was strategically used to endanger the global positions of their opponents. Thus, Bulgaria joined the Central Powers while Romania and Greece joined the Entente. Ottoman Turkey, endangered by Russia’s ambitions committed itself to the German war effort hoping to obtain a favorable post-war settlement. This time with the backing of Great Powers, the Balkan nations again resorted to weapons to fulfill their national plans and projects. Meanwhile, Albania, a newly established but weak state, temporarily lost its independence.[3] After the defeat of Serbia in the autumn of 1915, Albania was occupied by opposing powers – Italy and France on the one hand and Austria-Hungary on the other.[4]

In South East Europe, warfare became a mixture of conventional military approaches, harsh realities, and a violent tradition of local animosity. In addition, other features like irregular warfare, insurgency, epidemics, freezing winters, requisitions, hunger, and reprisals against civilian populations contributed to creating yet another extremely violent theater of the First World War. Perhaps more so than their European counterparts, soldiers from the Balkan armies, due to their combat experience from the recent Balkan wars, were very aware of the effects of artillery barrage or machine-gun fire. Austro-Hungarian soldiers had not experienced warfare for decades and the last great battle the Austrian army had fought, the Battle of Königgrätz in 1866, belonged to another epoch.

South East European battlegrounds↑

Presented here in chronological order, during the period 1914-1918 are the following South East European battlegrounds:

- The Austro-Hungarian offensive against Serbia and Montenegro from July until December 1914

- The battle of Gallipoli 1915

- The Austro-Hungarian-German-Bulgarian joint offensive against Serbia and Montenegro from October 1915 to January 1916

- The Romanian front 1916-1918

- The Macedonian front 1916-1918

The Austro-Hungarian Invasion of Serbia and Montenegro 1914↑

Immediately after the Austro-Hungarian ultimatum and proclamation of war, Serbia and Montenegro mobilized their armed forces. In total, Serbia mobilized around 400,000 soldiers in three army groups, with one cavalry and eleven infantry divisions as well as numerous auxiliary and irregular units,[5] while Montenegro mobilized around 40,000 soldiers. The Montenegrin forces were small, and due to its organization that followed traditional clan structures, resembled more a militia than a modern army. They were an experienced, battle hardened, and very motivated opponent.[6] Due to the long-term preparations for the Balkan wars, the Serbian and Montenegrin armies were armed with equally modern weapons and in some instances, such as rapid firing field artillery or machine guns, were more up to date than their Austro-Hungarian adversary.[7] The Austro-Hungarian Supreme command (k.u.k. Armeeoberkommando) engaged a total of three army groups, each with seven army corps containing one cavalry and seventeen infantry divisions.[8] However, one army had to be redeployed against Russia leaving only two armies in action against Serbia and Montenegro. Austro-Hungarian planning and initial action underestimated their opponent. Officers expected a punitive campaign (Strafaktion) against Serbia that would be "a brief autumn stroll".[9] A quick victory over Serbia would lead to its occupation and would free Austro-Hungarian troops to fight against Russia. The basic presumption of the Serbian-Montenegrin war plan was to maintain a defensive stand while at the same time attracting and engaging the Austro-Hungarian as much as possible forces in order to weaken their actions against Russia.[10]

The Serbian Supreme Command under Field Marshal Radomir Putnik (1847-1917) expected a major Austro-Hungarian attack from the north, across the Sava and Danube rivers following natural communication lines in the Morava valley. However, to Putnik’s surprise, it came from Bosnia and Herzegovina following the previous demands of Austro-Hungarian Chief of Staff Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf (1852-1925) in 1908 and again in 1912-1913, who thought that this would be the best tactic, as it disrupted Serbian influence in Bosnia and Herzegovina.[11] This necessitated a huge redeployment of Serbian forces to the west. The invading Austro-Hungarian troops were under the command of General Oskar von Potiorek (1853-1933). During their advance, Austro-Hungarian troops committed atrocities against Serbian civilians in the town of Šabac and western Serbia in general.[12] These events occurred against a background of existing anti-Serbian propaganda, which was only bolstered by the attacks of Serbian irregulars who in their appearance did not differ from civilian population.

The first battle happened between 17 and 19 August on the slopes of Cer Mountain in west Serbia where Austro-Hungarian forces were repelled with heavy losses, especially among officers and non-commissioned officers (NCOs). Although Serbian losses were smaller, they were nonetheless devastating as they could not be compensated with adequate replacements. The Battle of Cer was the first allied victory in the Great War. Further to the south, in mid-September, the Montenegrin army, together with a strong Serbian corps, initiated offensive actions against the Austro-Hungarian forces in the former Sanjak of Novi Pazar and Bosnia and Herzegovina. After the successful offensive and the capture of places like Pljevlja and Višegrad on 25 September, they took Pale in the vicinity of Sarajevo. This forced a redeployment of Habsburg troops and a counteroffensive in mid-October which, after the success in the Battle of Glasinac, forced the combined Serbian and Montenegrin units to withdraw across the river Drina.[13]

During the first days of September, the Austro-Hungarian army continued its offensive, resulting in a series of smaller clashes known as the Battle of Drina. There were, again, heavy losses on both sides which brought a stalemate and a short period of trench warfare to the battle in October.[14]

The third and final Austro-Hungarian offensive began on 6 November 1914. Outnumbered and suffering from a lack of ammunition, Serbian troops were forced to withdraw; even the Serbian capital Belgrade was evacuated. However, withdrawal made it possible for the Serbian army to regroup, replenish its ammunition supplies, and on 3 December, to launch a surprise counter-offensive against the exhausted and undermanned Austro-Hungarian troops whose supply lines had been over-stretched. The Austro-Hungarian defeat, known as the Battle of the River Kolubara, resulted in the expulsion of their troops from Serbia and the capture of a large number of Austro-Hungarian prisoners of war (POWs).[15] According to the data of Austro-Hungarian General Staff, Austria-Hungary engaged 450,000 soldiers and 12,000 officers on the Balkan front throughout 1914. From that number, 28,276 were killed in action, 2,046 captured, 76,644 missing in action, 122,122 wounded and 46,716 caught diseases – in total 275,000. Almost 60 percent were professional and not reserve soldiers and of the 275,000, 7,600 were officers.[16] On the Serbian side the heavy casualties of 2,110 officers, 8,074 NCOs and 153,373 soldiers (killed, wounded, captured and missing) were the price of Serbian victory in 1914.[17]

After intensive fighting, neither side could continue with offensive action, resulting in a long stalemate on the Balkan front from January to October of 1915. Another reason for the stalemate was an outbreak of a typhoid fever epidemic in January. The epidemic crippled the Serbian medical staff and caused severe losses among soldiers, civilians[18] and Austro-Hungarian prisoners of war.[19]

The Battle of Gallipoli 1915↑

From February 1915 until mid-January 1916 the Dardanelle Strait and the Peninsula of Gallipoli were the locations of the biggest landing operation in history at the time. In an attempt to take Constantinople, which would ease the pressure on Russia and would lead towards the expulsion of Turkey from the war, Allied (mostly British) war planners organized a massive military operation.[20] According to the plan, the navy would lead the attack against the fortified defense in Gallipoli. The destruction of these defenses would free the way towards the Marmara Sea and Constantinople itself. However, the operations of the British and French navies and armies were slow and they allowed Ottoman forces under the command of the German General Otto Liman von Sanders (1855-1929) to gather reinforcements and to strengthen their positions. Both the Allied fleet and army suffered heavy casualties. On the bridgeheads of Gallipoli, the Allies disembarked 410,000 British and 79,000 French soldiers of whom, when fighting ended, 205,000 British and 47,000 French soldiers were counted as causalities. Of the approximately 500,000 soldiers engaged on the Ottoman side, they lost 251,309. The Allied operation at Gallipoli remains one of the most controversial operations in regard to its expectations, possible outcomes and influences it had on further events in the First World War.[21]

The Austro-Hungarian – German – Bulgarian Invasion against Serbia 1915↑

Although Serbia and Montenegro were primarily an Austro-Hungarian concern, during 1915 the Balkan areas attracted the attention of German military planers. In order to assist the Ottoman Empire, Germany opened negotiations with Bulgaria as well as preparations with Austro-Hungary for military action against Serbia and Montenegro.[22] Both the Allies and Central Powers attempted to draw Bulgaria in on their side with offers of Serbian and Greek territorial concessions. German diplomacy was successful and in the first days of September Bulgaria joined the Central Powers. In order to ease its situation, Serbia suggested a preemptive strike before Bulgaria could finish the mobilization and concentration of its troops, but the western Allies strongly opposed to this proposal.[23]

For the execution of the offensive against Serbia, Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Bulgaria deployed three army groups under the command of German General August von Mackensen (1849-1945) and one under the Bulgarian Supreme command. Serbian forces were divided and outnumbered two-to-one. The German-Austrian offensive began on 6 October and the Bulgarian offensive on 14 October 1915. German planners did not repeat Austro-Hungarian mistakes from the previous year. They attacked from the north following natural communications through the Morava valley. Throughout the campaign, German advances were marked by intensive fire of large caliber artillery for which the Serbian army did not have an adequate response. Again helped by the small Montenegrin army, Serbian forces slowly withdrew followed by thousands of refugees. Nevertheless, the Serbian army carried out an orderly retreat avoiding being surrounded on several occasions, and organizing several counterstrikes. Meanwhile, the Greek King, Constantine I, King of Greece (1868-1923) deposed the pro-Allied Prime Minister Eleutherios Venizelos (1864-1936), thus preventing Greece from entering the war on the side of the Entente. Serbia and Montenegro’s position became extremely difficult.[24] The Anglo-French contingent that had landed in Salonika was too weak to assist the Serbians although it went up to the Krivolak in Macedonia in an attempt to ease Bulgarian pressure. By the end of November, the German plan of defeating the Serbian army was accomplished. The remnants of the Serbian army, together with its king, government and thousands of refugees withdrew across the Albanian Alps towards the Adriatic coast. During the withdrawal they were decimated by hunger, winter, diseases and Albanian attacks. From there, French and Italian navies transported them to the Greek island of Corfu where they recovered and reorganized.[25] The Serbian withdrawal was protected by the resistance of Montenegrin troops under the command of General Janko Vukotić (1866-1927), which managed to inflict a heavy blow on Austro-Hungarian troops in the Battle of Mojkovac on 6 and 7 January 1916, preventing them from cutting off the Serbian retreat. However, under Bulgarian pressure Allied troops withdrew to Salonika while Austro-Hungarian troops from Bocca di Cattaro launched an offensive against Montenegro. As in the Serbian example, intensive large caliber artillery fire, especially from Austro-Hungarian warships, was crucial for the breakthrough of Montenegrin defense lines in the area of Mount Lovćen and the subsequent fall of the Montenegrin capital Cetinje. Nikola I, King of Montenegro (1840-1921) left the country while the army was forced to surrender on 16 January. Some 15,000 Montenegrins, soldiers and civilian were taken as POWs and sent to Austro-Hungarian POW and internment camps.[26]

The Romanian Front 1916 – 1918↑

During the July Crisis in 1914, Romania did not enter the war on the side of the Central Powers. Although it was bound to Austria-Hungary by a secret defensive military alliance, this became inoperable due to Austria-Hungary’s declaration of war on Serbia.[27] In addition, due to the intensive political activity of Romanian Prime Minister Ion Brătianu (1864-1927), Romania shifted its foreign policy towards the Entente. Strong pro-French sentiment in Romania as well as territorial disputes over Transylvania contributed to this change.[28] The Entente offered guarantees on the future unification of Romania with its surrounding Austro-Hungarian provinces. However, Romania did not enter the war until August 1916.[29] Although the Romanian army numbered 800,000 men in total, compared to its opponents it suffered from serious shortages of modern weapons like machine guns and rapid firing artillery. Both the officer and the NCO corps were inadequate in number and in military preparation, and their tactics were inadequate for modern warfare.[30]

Upon entering the war, Romania acted in cooperation with Russia which led to extension of Eastern front for 500 kilometers to the south. The Romanian offensive in Transylvania against Austria-Hungary was too slow and allowed their opponents to regroup forces and in turn conduct a successful counteroffensive.[31] Meanwhile, in the South, in Dobruja, joint German, Bulgarian and Ottoman forces, despite the assistance of Russian troops and one Serbian division, pushed slowly to the north.[32] By December they had captured the Romanian capital of Bucharest. The Romanian army withdrew to the north leaving its richest province, Wallachia, in the hands of the Central Powers. With French aid, Romanian troops were reorganized and together with Russian troops they launched an offensive in July 1917. Initially it was successful. In August, however, another counteroffensive by the Central Powers stopped the offensive, eventually leading to prolonged trench warfare. The battles of Maraşti (24 July-1 August), Maraşeşti (6 August-3 September), Oituz (8-21 August), and Cireşoaia (9-10 September) occurred during these operations. Unlike the 1916 campaign, these battles, were the only Allied successes in 1917, helping to reestablish Romanian credibility in the eyes of the Allies.[33] However, by the end of 1917, due to the Russian revolution, approximately 1,200,000 Russian soldiers withdrew, which led to the armistice and eventually a separate peace between Romania and the Central Powers in May 1918. Romania again shortly entered the war in November 1918, only hours before the armistice in the west.[34]

The Macedonian Front 1916 – 1918↑

The arrival of the first Allied troops in Salonika in 1915 marked the appearance of a new battleground in South East Europe. After the failure to reach and support their Serbian allies, French and British troops confined themselves to heavily fortified positions around Salonika. The Bulgarian army leadership insisted on initiating an attack against Greece, whose soil was used by Allied forces but the German supreme command strongly opposed these plans.[35]

An already complex picture became more complex with the arrival of new Allied troops as well as with further complications in Greek internal politics. In summer 1916, the recovered and rearmed Serbian army arrived in Salonika. Here, the front lines of the Macedonian front stretched from the Albanian coast across the Macedonian mountains to the Aegean coast in Thrace, and remained more or less unchanged until the breakthrough in mid-September 1918.

The Macedonian front is interesting because it was the perhaps the most diverse front in terms of participants on both sides. On the Allied side there were French and British troops (with their colonial contingents from Senegal, Morocco, Madagascar, India and French Indochina), followed by Italians, Russians, Serbians, a small Albanian contingent under Essad Pasha Toptani (c. 1863-1920), and finally the Greeks who joined the Allied side during 1917. Opposing them were Austro-Hungarians, Germans, Bulgarians, and for some period even Turks with one army corps.[36] On the eve of breakthrough, the front consisted of 600,000 Bulgarian, Austro-Hungarian, and German soldiers on the Central Powers side, while Allied troops consisted of 180,000 French, 140,000 Serbian, 135,000 Greek, 120,000 British, 42,000 Italian and 2,000 Albanian soldiers – 619,000 in total.[37] All participants on the Macedonian front were faced with prolonged trench warfare, soldier dissatisfaction and mutinous behavior. After the revolutionary events in Russia, the Russian contingent on the Macedonian front had to be withdrawn from the front line.[38] There were also cases of fraternization between Bulgarian and Serbian soldiers in no man's land. Finally, right after the breakthrough and during the withdrawal of the defeated Bulgarian troops, an attempted soldiers’ revolution against the Bulgarian regime took place.[39]

Several battles occurred on the Macedonian front. From 17 August to 20 November 1916 in the battles of Gorničevo, Kaimakčalan Mountain and the Crna reka valley, Allied troops managed to suppress offensives by the Central Powers and pushed them some forty kilometers to the north in turn taking the city of Monastir (Bitola).[40] The first Greek units started to arrive after the official entry of Greece into the war on the Allied side in June 1917. In spring 1918, they launched a successful offensive against the fortified area of Skra di Legen.[41] Most of the time, however, the Macedonian front did not attract the attention of the Allied command structures. After many disputes and changes of supreme commanders General Maurice Saraille (1856-1929), and finally Louis Franchet d’Espèrey (1856-1942), an offensive was scheduled for mid-September 1918. This was a complete Allied success, which, from a military point of view, was a carefully prepared and conducted offensive action which resulted in a decisive breakthrough of the front and decisive defeat of the opponent.[42] Although the Battle of Doiran represented a Bulgarian tactical success, it could not prevent the collapse of the front when the Bulgarian lines at Dobro Polje were breached. During the Battle of Doiran, both sides used gas shells against their enemy making it the first use of this kind of weapon on the Salonika front.[43] In the advancement of Allied troops following the breakthrough of the Salonika front, Serbian troops entered Veles and Štip on 26 September, while the French cavalry took Skopje in a surprise attack on 29 September 1916. The Battle of Dobro Polje and the collapse of the Bulgarian army in Macedonia led to the expulsion of Bulgaria from the war. Bulgarian emissaries signed an armistice in Salonika on 30 September.[44] After the expulsion of the Bulgarian army, German and Austro-Hungarian commands could not bring enough troops to plug all the holes on the Balkan front. When Serbian troops took the town of Niš on 12 October, all land communications with the Ottoman Empire were cut off.[45] This allowed Allied troops from the Salonika front to march to Constantinople, force Austro-Hungarians to evacuate Albania, and send one detachment toward the Danube and assist the Romanians.

Soon after, the Ottoman Empire signed an armistice in Mudros on 30 October. The strong pressure of the advancing Allied forces and the activities of local insurgents forced the German and Austro-Hungarian troops to abandon Serbia and Montenegro by the end of October.[46] Finally, the Battle of Dobro Polje and the breakthrough on the Salonika front contributed to the process of the disintegration of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and announced the creation of Yugoslav state.[47]

Small Wars and Insurgencies↑

During the Great War, South East Europe was a theater of intensive irregular warfare, namely small wars, spontaneous armed resistance and insurgencies. Here, the irregular warfare was strongly imbedded in local military traditions stemming from the time of Ottoman occupation. For Balkan Christians, and later Albanians, irregular warfare was the only way to fight against Ottoman military supremacy. Later, by the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, newly established independent Balkan Christian states such as Bulgaria, Greece, Serbia and Montenegro resorted to different kinds of irregular activities (chetniks, komitajis, klefts and armatoles) as a way of expanding their influence in territories which remained under Ottoman rule (Sanjak, Kosovo and Metohija, Macedonia, and Thrace) and simultaneously struggling against rival organizations. Through their own national movement Albanians soon followed their own outlaws known as kachaks. By the beginning of the 20th century they organized a series of uprisings against the Ottoman authorities.

The first test for the official engagement of irregulars was during the Balkan wars 1912-1913. Bulgarians decided to use their own comitaji fighters from the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO). Several hundred of them were gathered in so-called "Guerrilla Detachments". Their leaders were promoted to officer and NCO ranks, giving the whole enterprise a strict military appearance. The majority of common members were experienced IMRO fighters from the ranks of Macedonian émigrés residing in Bulgaria. Guerrilla detachments were divided into platoons with the main task of performing reconnaissance missions in front of the advancing army.[48]

The Serbian army could count on the services of chetnik units. The total number of chetniks which fought in the ranks of the Serbian army varied between 2,000 and 4,000. They formed some ten Serbian chetnik detachments.[49] Beside officers and NCOs there were nationalists, such as university and high school students, volunteers from Austria-Hungary and Montenegro, members of the Serbian gendarmerie and border troops, as well as Macedonian refugees and seasonal workers in Serbia and local Macedonian peasants. The secret organization "Unification or Death", better known as the "Black Hand" exerted a crucial influence on the organization of Serbian irregulars. Many of the "Black Hand" members had already actively participated in chetnik action.

In the Greek army there were several different irregular units commonly named Volunteer Scouts units. Many of them were experienced guerrilla fighters from the time of the Macedonian struggle of 1908 or were members of the Pan-Hellenic Organization, which had some hundred officers and NCOs operating in Ottoman Macedonia and Thrace from 1909. In total, there were more than 8,000 members within different irregular Greek units.[50] During the Balkan Wars, these irregulars became the main perpetrators of various war crimes against civilian population such as reprisals, arson and pillaging.

During the Great War, both sides in the Balkan war theater continued to use irregulars as auxiliary units. One purpose was to fight against their enemies while another was the enforcement of Central powers' occupations. In addition, harsh occupation regimes facilitated the emergence of armed resistance through the actions of small groups which ambushed army and police patrols and forage units as in Montenegro or led to uprisings which in return caused severe reprisals against the insurgents as in case of the Toplica uprising in Serbia in 1917.

Small wars↑

Following previous experiences, the Serbian and Bulgarian armies relied to a great extent on the actions of irregular units. Their members had vast experience from the years of armed action in Ottoman Macedonia, especially in the period between 1903 and 1912, when they confronted each other as well as Ottoman regulars and irregulars.

The Serbian supreme command organized four detachments of 2,250 irregulars (chetniks).[51] These detachments operated under the command of officers with previous experience in irregular warfare and were planned to operate in the enemy rear as reconnaissance units or to create diversions against enemy supply lines, communications and headquarters. According to Austro-Hungarian reports from 1914, Serbian irregulars disrupted communications and supply lines and affected the morale of Austro-Hungarian troops.[52] A constant fear of their action was present and these actions often caused severe reprisals against the Serbian civilian population.[53]

The Bulgarians also used the services of komitaji fighters, members of IMRO, in "Guerrilla detachments". Their main task was reconnaissance and creating diversions in front of the advancing army. There were some 500 comitajis in the Guerrilla detachment.[54] However, IMRO members had already carried out several operations against Serbian troops and infrastructure in Macedonia during 1914 and 1915, of which the best known is the Good Friday attack (Valandovska afera) of 20 March 1915 on the railroad near Valandovo, where some 1,500 komitajis, together with one Turkish irregular detachment inflicted serious causalities to Serbian 3rd line troops guarding the railway and bridge.[55] This action and many others were financed by Austria-Hungary through its military attaché in Sofia.[56]

After the Serbian withdrawal across Albania, most of the Serbian irregulars were grouped in a volunteer detachment assigned to participate in conventional warfare. Due to the heavy causalities during the battle for Kaimakčalan Mountain in 1916, the remaining soldiers of the volunteer detachment were dispersed among regular troops.

The Austro-Hungarian military also relied on irregular troops, consisting of Albanian clansmen, mostly from northern Albania and Kosovo. After 1916 and the formation of a front line in Albania, they proved very useful in the rough conditions of Albania where Austro-Hungarian regular troops suffered from the adverse effects of the local climate and malaria.[57]

Insurgencies↑

After the Serbian defeat in the autumn of 1915, the Austro-Hungarians organized their occupation as k.u.k. Militärgeneralgouvernement Serbien. Bulgarians, however, considered the occupied areas (Macedonia and South Serbia) as already annexed while the local population was considered Bulgarian. Harsh occupation regimes in both zones gradually led to armed resistance. The measures taken in the Austro-Hungarian zone included taking hostages, requisitions, internment, press censorship, martial law, changes in school the curriculum and a ban on the Cyrillic alphabet, and giving privileges to friendly minorities.[58] Bulgaria implemented a thorough policy of denationalization of the Serbian population in South Serbia and Macedonia. They banned the Serbian Cyrillic alphabet, Serbian names and surnames, national costumes and folklore. They introduced a "Bulgarian" curriculum into schools, and imported Bulgarian teachers and priests. These measures were followed by the internment of members of the Serbian intelligentsia, especially teachers and priests.[59]

The organization of armed resistance in Serbia and Montenegro probably began spontaneously when occupiers started looking for Serbian and Montenegrin soldiers who had returned to their homes rather than withdrawing across Albania.[60] In both occupation zones armed individuals as well as smaller groups started to appear. In the beginning they were without leadership and organizational unity.[61] Meanwhile, the Serbian supreme command was fully aware of the existing potential for irregular warfare. In order to prepare and organize a mass uprising that would help the Allied advancement after the expected breakthrough on the Macedonian front, in September 1916 they sent Kosta Milovanović-Pećanac (1879-1944) to Serbia. He was a reserve officer and experienced chetnik from the period of Serbian action in Ottoman Macedonia. After arriving by plane, he began organizing irregular units for the expected Allied offensive. However, during the winter months the Bulgarian attempts to mobilize Serbian youths led to an open mass uprising. By the end of February 1917, uprisings broke out in the Toplica region in the Bulgarian occupied zone as well as in the southern part of the Austro-Hungarian occupied zone. Insurgents liberated several smaller towns and vast rural areas surrounding them.

This was a signal for drastic measures by the Bulgarian occupation authorities.[62] The quelling of the rebellion was assigned to Colonel Alexandar Protogerov (1867-1928), head of the Bulgarian military authorities in South Serbia and one of the highest ranking officials of the IMRO.[63] Bulgarians brought additional forces and engaged prominent komitaji leaders and their units. They had fifteen battalions with twenty-eight machine guns and twenty-eight canons. The Austro-Hungarians, in turn, strengthened the borders between the two occupation zones and participated in a counter-strike against the uprising. They engaged ten different battalions and one armored train. Both Austro-Hungarians and Bulgarians also engaged different irregular units consisting of Albanians.[64] The actions of the Bulgarian and Austro-Hungarian forces and irregulars were marked by brutality against the civilian population. During the quelling of the rebellion by the end of March 1917 some 20,000 civilians had been murdered. Despite repressive measures and defeat, most of the insurgents continued their struggle, waging a guerrilla campaign which proved extremely valuable when the actual Allied offensive began in mid-September 1918.[65]

Conclusion↑

For most nations of South East Europe the First World War represented a continuation of previous wars. Unlike the years before the outbreak of the war, when the main instrument for the settlement of Balkan disputes and crisis was diplomatic pressure from the Great Powers, this time the Great Powers came to South East Europe with their armies and navies. As elsewhere, the First World War in South East Europe was brutal and bloody, and the death toll among the civilian population was extremely high, although the exact number of civilian causalities reamin unknown due to hunger, harsh occupation, and the Spanish flu pandemic immediately after the war.

Unlike the Western Front, which mostly remained unchanged due to the equality of opponents, the war in South East Europe was marked by a high dynamic in planning and conducting of military operations. For example, several towns, like Belgrade and Šabac experienced several changes of military regimes in a short period of time. Again, as in previous conflicts a tradition of irregular warfare and irregular units had their own, important role; one which was in close connection with armed resistance – the traditional remedy for the harsh occupation regimes. However, most of the issues which existed in South East Europe existed before the First World War and carried on after the Armistice. In some cases (like relations between Yugoslavia, Greece, and Romania with Bulgaria) these issues were deepened by the outcome of the First World War, causing the above-mentioned nations to once again take up opposing sides in future conflicts.

Dmitar Tasić, Institute for Strategic Research

Section Editors: Milan Ristović; Richard C. Hall; Tamara Scheer

Notes

- ↑ Le Moal, Frédéric: La Serbie. Du martyre à la victorie 1914 – 1918, Paris 2008. p. 218.

- ↑ Newman, John Paul: The Origins, Attributes, and Legacies of Paramilitary Violence in the Balkans, in: Gerwarth, Robert/Horne, John (eds): War in Peace. Paramilitary Violence in Europe after the Great War, Oxford 2011, pp. 145-163.

- ↑ Bartl, Peter: Albanci, od Srednjeg veka do danas [Albanians, from the Middle Ages until Today], Belgrade 2001, pp. 174-178.

- ↑ Bartl, Albanci [Albanians] 2001, pp. 170-172.

- ↑ Le Moal, La Serbie 2008, p. 46.

- ↑ Skoko, Savo/Opačić, Petar: Vojvoda Stepa Stepanović u ratovima Srbije 1876-1918 [Field marshal Stepa Stepanović in Serbia’s Wars 1876 – 1918], Belgrade 1974, p. 319.

- ↑ Schindler, John R.: Disaster on the Drina: The Austro-Hungarian army in Serbia, 1914, in: War in History 9/2 (2002), pp. 159–195. For another contribution on this subject see also: Ortner, Mario Kristijan: Rat protiv Srbije 1914. i 1915. (Pogled iz Austrije) [War against Serbia 1914 and 1915 (Austrian Perspective)], in: Vojnoistorijski glasnik [Military History Review] 1 (2010), pp. 111-132.

- ↑ Schindler, Disaster on the Drina 2002, p.165.

- ↑ Schindler, Disaster on the Drina 2002, p. 166.

- ↑ Opačić, Petar: Ratni plan austrougarskog generalštaba za rat protiv Srbije I ratni plan srpskog generalštaba za odbranu zemlje od austrougarske agresije [War plan of the Austro-Hungarian General Staff for the war against Serbia and war plan of the Serbian General Staff for the defence of country against Austro-Hungarian aggression] in Čubrilović, Vasa (ed.): Velike sile i Srbija pred Prvi svetski rat, Zbornik radova prikazanih na međunarodnom naučnom skupu Srpske akademije nauka u umetnosti održanom 13.-15. septembra 1974. u Beogradu [Great Forces and Serbia on the Eve of First World War, Conference proceedings 13-15 September 1974, Belgrade, Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts], Belgrade 1974, p. 517.

- ↑ Ortner, Rat protiv Srbije 1914. i 1915 [War against Serbia 1914 and 1915] 2010, p. 116.

- ↑ Reiss, Archibald Rodolphe: Report upon the atrocities committed by the Austro-Hungarian army during the first invasion of Serbia, Simpkin, London 1916, p.141. According to the well documented investigation carried out immediately after the withdrawal of Austro-Hungarian troops some 1,300 civilians were found killed by the Austro-Hungarian troops (994 men, 306 women and eighty-seven children) while 489 men, seventy-three women and twenty children were stated as missing. Victims were hanged, shot, or bayoneted while some were even burned alive inside their homes. Several cases of rape were documented as well (the actual number was probably higher because of traditional, patriarchal upbringings, where such cases were considered shameful and kept secret). Beside these numbers some 1,500 citizens of Šabac were taken away as hostages. The majority of them died in captivity.

- ↑ Le Moal, La Serbie 2008, p. 49.

- ↑ Only in the clashes on positions of Mačkov kamen and Košutnja stopa from 14 to 22 September both Dunav divisions (1st and 2nd line) had 11,490 causalities. See: Skoko/Opačić, Vojvoda Stepa Stepanović [Field marshal Stepa Stepanović] 1974, p. 393.

- ↑ According to the register of Serbian POW command, at the beginning of the January 1915 there were 568 officers and 54,906 Austro-Hungarian soldiers in Serbian custody. See: Đukić, Slobodan: Austrougarski ratni zarobljenici u Srbiji 1914-1915. godine [Austro-Hungarian prisoners of war in Serbia 1914-1915], in: Prvi svetski rat i Balkan – 90 godina kasnije, Tematski zbornik radova. Institut za strategijska istraživanja [First World War and the Balkans – 90 years after, Collections of papers, Strategic Research Institute], Belgrade 2010.

- ↑ Ortner, Rat protiv Srbije 1914. i 1915 [War against Serbia 1914 and 1915] 2010, p. 126.

- ↑ Skoko/Opačić, Vojvoda Stepa Stepanović [Field marshal Stepa Stepanović] 1974, pp. 465-466.

- ↑ It is estimated that 100,000 civilians and 35,000 soldiers died from typhoid fever, see: Mitrović, Andrej: Serbia’s Great War 1914-1918, Bllomington 2006, p. 111.

- ↑ During the winter months some 20,000 Austro-Hungarian POWs died from typhoid fever, see: Đukić, Austrougarski ratni zarobljenici u Srbiji 2010, p. 145.

- ↑ Moorehead, Alan: Gallipoli, New York 2002. Another contribution on this subject: Travers, Tim: The Ottoman Crisis of May 1915 at Gallipoli, in: War in History 8/2 (2001), pp. 72-86.

- ↑ Morehead, Gallipoli 2002, p. 355.

- ↑ Ortner, Rat protiv Srbije 1914. i 1915 [War against Serbia 1914 and 1915] 2010, p. 128.

- ↑ Le Moal, La Serbie 2008, p. 85.

- ↑ Katsikostas, Dimitrios: The outbreak of the Hellenic split in the context of the WWI, in: Prvi svetski rat i Balkan – 90 godina kasnije, Tematski zbornik radova [First World War and the Balkans – 90 years after, Collections of papers, Strategic Research Institute], Belgrade 2010, pp. 81-94; Mitrović, Andrej: Insurgency and Follow up Fighting in Serbia 1916 – 1918, Belgrade 1987.

- ↑ Le Moal, La Serbie 2008, pp. 100-102.

- ↑ Le Moal: La Serbie 2008, pp. 99-100.

- ↑ Dumitru, Laurenţiu Cristian: July – August 1914. Romania Denies to Attack Serbia, in: Prvi svetski rat i Balkan – 90 godina kasnije, Tematski zbornik radova. Institut za strategijska istraživanja [First World War and the Balkans – 90 years after, Collections of papers, Strategic Research Institute], Belgrade 2010, pp. 9-18.

- ↑ Torrey, Glenn E.: The Romanian Battlefront in World War I, Kansas 2012, p. 3.

- ↑ Dumitru, July – August 1914. Romania Denies to Attack Serbia, pp. 9-18.

- ↑ Torrey, The Romanian Battlefront 2012, pp. 14-21.

- ↑ For the most recent contribution to the analyses of Romanian participation in the Great War, see: Torrey, The Romanian Battlefront 2012.

- ↑ Torrey, The Romanian Battlefront 2012, pp. 113-116.

- ↑ Torrey, The Romanian Battlefront 2012, pp. 332.

- ↑ Torrey, The Romanian Battlefront 2012, pp. 333.

- ↑ Cruttwell, C. R. M. F.: A History of the Great War 1914 -1918, Chicago 2007, p. 233.

- ↑ Hall, Richard C.: Balkan breakthrough. The battle of Dobro Pole 1918, Bloomingtom 2010, p. 74.

- ↑ Solunski front, Vojna enciklopedija 8, Belgrade 1976, p. 787.

- ↑ Hall, Balkan breakthrough 2010, p. 97.

- ↑ B’lgarskata armia 1877-1919 [Bulgarian armed forces], Sofia 1988, pp. 298-304.

- ↑ Ratković – Kostić, Slavica: Vojska Kraljevine Srbije 1916. i 1917. godine. Organizacija i formacija [Armed forces of the Sebian Kingdom 1916 and 1917. Organization and formation], in: Prvi svetski rat i Balkan – 90 godina kasnije, Tematski zbornik radova. Institut za strategijska istraživanja [First World War and the Balkans – 90 years after, Collections of papers, Strategic Research Institute], Belgrade 2010, pp. 101-117.

- ↑ A History of the Hellenic Army, Athens 1999, pp. 132 – 133.

- ↑ Hall, Balkan breakthrough 2010, p. 144.

- ↑ Hall, Balkan breakthrough 2010, p. 141-143.

- ↑ Opačić, Petar: Srbija i Solunski front [Serbia and Macedonian Front], Belgrade 1984, p. 305.

- ↑ Opačić, Srbija i Solunski front [Serbia and Macedonian Front] 1984, p. 330.

- ↑ Opačić, Srbija i Solunski front [Serbia and Macedonian Front] 1984, pp. 360 and 366.

- ↑ Opačić, Srbija i Solunski front [Serbia and Macedonian Front] 1984, p. 369.

- ↑ Minchev, Dimitar: Participation of the population of Macedonia in the First World War 1914 – 1918, Sofia 2004, p. 53.

- ↑ Ilić, Vladimir: Učešće srpskih komita u Kumanovskoj operaciji 1912. Godine [Participation of Serbian comitaji¨s in Kumanovo operation 1912], in: Vojnoistorijski glasnik [Military History Review], 1-3 (1992), p. 200.

- ↑ A Concise History of the Balkan Wars 1912-1913, Army History Directorate, Athens 1998, p. 17.

- ↑ Pavlović, Živko: Bitka na Jadru 1914. Godine [Battle of river Jadar 1914], Belgrade 1924, Prilog: Formacija četničkih odreda za rat sa Austro-Ugarskom 1914. Godine [Apendix: Formation of the chetniks detachments for the war aginst Austria-Hungary 1914].

- ↑ Schindler, Disaster on the Drina 2002, pp. 165, 169, 171, 173, 178, 183, 185.

- ↑ Pollman, Ferenc: Austro-Hungarian atrocities against Serbians during WWI (Šabac, 17 August 1914) in: Prvi svetski rat i Balkan – 90 godina kasnije, Tematski zbornik radova. Institut za strategijska istraživanja [First World War and the Balkans – 90 years after, Collections of papers, Strategic Research Institute], Belgrade 2010, pp. 135-141.

- ↑ Minchev, Participation of the population of Macedonia in the First World War 2004, pp. 51-56.

- ↑ Marić, Ljubomir: Valandovski zločin i njegove žrtve [The Valandovo Atrocity and its Victims], in: Ratnik [Warrior] IV (1930), pp. 19-31.

- ↑ Minchev, Participation of the population of Macedonia in the First World War 2004, p. 52.

- ↑ Pollman, Ferenc: Albanian irregulars in the Austro-Hungarian army during World War I, in: Raugh, Harold E. Jr (ed): Regular and Irregular Warfare: Experiences of Historical and Contemporary Armed Conflicts, Belgrade 2012. pp. 63-68.

- ↑ Scheer, Tamara: Forces and Force. Austria-Hungary’s occupation regime in Serbia during the First World War in: Prvi svetski rat i Balkan – 90 godina kasnije, Tematski zbornik radova. Institut za strategijska istraživanja [First World War and the Balkans – 90 years after, Collections of papers, Strategic Research Institute], Belgrade 2010, pp. 161-179.

- ↑ Istorija srpskog naroda VI -2, Od Berlinskog kongresa do ujedinjenja 1878 – 1918, SKZ [History of the Serbian Nation VI-2, From the Berlin Congress until Unification 1878-1918], Belgrade 1994, p. 150.

- ↑ Mitrović, Serbia’s Great War 2006, p. 245.

- ↑ Mitrović, Insurgency and Fighting 1987, pp. 133-149.

- ↑ For the most detailed contribution on irregular warfare and insurgency in Serbia during WWI, see: Mitrović, Insurgency and Fighting 1987.

- ↑ Pisari, Milovan: Gušenje Topličkog ustanka: VMRO na čelu represije [Quelling of the Toplica uprising: IMRO on the forehead of represion], in Vojnoistoprijski glasnik [Military History Review] 2 (2011), pp. 28-21.

- ↑ Istorija srpskog naroda VI -2, [History of the Serbian Nation VI-2] Belgrade 1994, pp. 190-191.

- ↑ Le Moal, La Serbie 2008, p. 128.

Selected Bibliography

- Bartl, Peter: Albanci. Od srednjeg veka do danas (Albanians. From medieval times till present), Belgrade 2001: Clio.

- Cruttwell, C. R. M. F.: A history of the great war, 1914-1918, Oxford 1936: Clarendon Press.

- Čubrilović, Vasa (ed.): Velike sile i Srbija pred prvi svetski rat. Zbornik radova prikazanih na međunarodnom naučnom skupu Srpske akademije nauka i umetnosti, održanom od 13-15, septembra 1974. Godine u Beogradu (Great forces and Serbia on the eve of the First World War. Conference proceedings 13-15 September 1974), Belgrade 1976: Srpska akademija nauka i umetnosti.

- Hall, Richard C.: Balkan breakthrough. The Battle of Dobro Pole 1918, Bloomington 2010: Indiana University Press.

- Hellenic Army General Staff (ed.): A history of the Hellenic Army 1821-1997, Athens 1999: Hellenic Army General Staff Army History Directorate.

- Institut za strategijska istraživanja: Prvi svetski rat i Balkan – 90 godina kasnije, Tematski zbornik radova (First World War and the Balkans – 90 years after. Collections of papers), Belgrade 2010: Institut za strategijska istraživanja.

- Karastoânova, Lûbimka / Šanov, Stefan: B"lgarskata armiâ, 1877-1944 (Bulgarian armed forces, 1877-1944), Sofia 1989: Voenno izdatelstvo.

- Mario, Ortner Kristijan: Rat protiv Srbije 1914. i 1915. Pogled iz Austrije (The war against Serbia 1914-1915. The Austrian perspective), in: Vojno-istorijski glasnik/1 , 2010, pp. 111-132.

- Minchev, Dimitre: Participation of the population of Macedonia in the first World War, 1914-1918, Sofia 2004: Voenno Izdatelstvo.

- Mitrović, Andrej: Ustaničke borbe u Srbiji 1916-1918 (Insurgent fights in Serbia 1916-1918), Belgrade 1987.

- Mitrović, Andrej: Serbia's Great War, 1914-1918, London 2005: C. Hurst & Co.

- Mitrović, Andrej: Serbia's Great War, 1914-1918, West Lafayette 2007: Purdue University Press.

- Moal, Frédéric Le: La Serbie. Du martyre à la victoire, 1914-1918, Saint-Cloud 2008: 14-18 éd..

- Moorehead, Alan: Gallipoli, New York 1956: Harper.

- Opačić, Petar: Srbija i Solunski front (Serbian and Macedonian front), Belgrade 1984: Književne novine.

- Pavlovic, Živko G.: Bitka na Jadru avgusta, 1914 godine (Battle of river Jadar, 1914), Belgrade 1924: Grafički zavod 'Makarije'.

- Popov, Čedomir / Mitrović, Andrej: Istorija srpskog naroda. Od Berlinskog kongresa do ujedinjenja 1878-1918 (History of the Serbian nation. From the Berlin Congress till unification 1878-1918), volume 6, Belgrade 1983: Srpska književna zadruga.

- Schindler, John: Disaster on the Drina. The Austro-Hungarian army in Serbia, 1914, in: War in History 9/2, 2002, pp. 159-195.

- Skoko, Savo / Opačić, Petar: Vojvoda Stepa Stepanović u ratovima Srbije 1876-1918 (Field marshall Stepa Stepanović in Serbia’s Wars 1876-1918), Belgrade 1974: Beogradski izdavačko-grafički zavod.

- Torrey, Glenn E.: The Romanian battlefront in World War I, Lawrence 2011: University Press of Kansas.

- Voenno izdatelstvo (ed.): P’rvata svetovna voina na Balkanite (First World War in the Balkans), Sofia 2006: Voenno izdatelstvo.