Front Line Souvenirs?↑

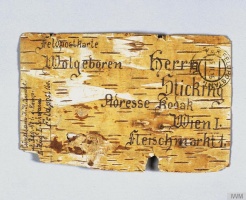

Only a minority of trench art was made in trenches. The creative impulses of men serving on the frontline were limited by physical circumstance. Nevertheless, there are some very simple examples of trench art, which would have served the dual purpose of providing a souvenir of the front and whiling away the maker’s time. Paper-knives were beaten out of the copper used to make the driving-bands of shells. Brass shell cases could be simply inscribed with extemporized tools. Finger-rings were formed from aluminium and copper. Wood – including bark and leaves – could be worked, or even the chalk into which some trenches were cut.

More elaborate assemblages of battlefield salvage were the province of those who had access to workshops – engineers and service corps personnel. The presence of their insignia on surviving examples of complicated metallic trench art confirms this. They follow numerous forms, ranging from crucifixes and model aircraft to smoker’s requisites such as tobacco boxes, matchbox covers and ashtrays.

A Wartime Trade↑

Those who could not create had the opportunity to purchase. On every front, local civilians and prisoners of war (POWs) sought to turn the presence of souvenir-hungry soldiers to their own profit. For prisoners and internees held in camps, such creativity also mitigated the oppressive dreariness – le cafard – of their captivity.

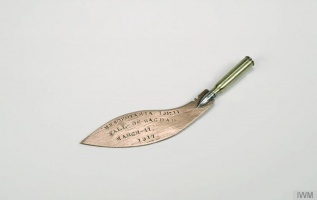

Frequently, traditional crafts were adapted to create new "product lines". Northern French lace-makers produced embroidered lace-edged postcards with patriotic or sentimental messages. Turkish prisoners of war sold their captors snakes made with coloured beads or tobacco jars of damascened metalwork. Egyptian civilians offered simple cable-stitch embroideries, while craftsmen in Mesopotamia made sophisticated niello jewellery. Meanwhile, German POWs and internees in Britain carved and painted the bones of the animals which had provided their food.

The output of some of these manufacturers reached impressive levels. At Amarah in Mesopotamia, a silversmith named Zahrum gained fame throughout the invading Indian and British forces as "the silver identity disc man". In 2001, large quantities of partially-worked trench art were discovered by French archaeologists at the site of a brass-work trench art "factory" run by a German POW labour company based near Arras during 1919.

Mending Men↑

Another important iteration of so-called trench art is the material created as a result of programmes aimed at rehabilitating the wounded through occupational therapy. At the simplest level, this consisted of embroidery work – something which could be done by bedridden men. There is evidence that this was sometimes done by men in acute pain, rather than by convalescents – for example at the Royal Victoria Hospital at Netley in Hampshire.

Britain, France and the USA all established workshops in which convalescing men could make wooden "toys". In Britain the lead was taken by the Lord Roberts Memorial Workshops, which found that working treadle-driven fret-saws was efficacious in building up wasted leg muscles. It was seen as an added advantage that toy-making was perceived as "capturing" a "pre-eminently German trade."[1]

Beadwork, basketwork, modelling with reclaimed tinfoil and making stationery from recycled paper also featured among therapies for the wounded.

Legacy↑

A huge amount of First World War trench art survives to this day and, since 1918, has been augmented by pseudo-trench art produced to cater to the battlefield tourist market on the former Western Front. In recent times, it has become accepted that this manifestation of First World War material culture is far from trivial or ephemeral, but that it offers crucial insights into people’s experience of, and engagement with, the war.

Paul Cornish, Imperial War Museums

Section Editor: Mark Jones

Notes

- ↑ Exhibition for encouraging work done by wounded and discharged soldiers and sailors, 20 June to 27 June 1917, London 1917, p. 37.

Selected Bibliography

- Exhibition for encouraging work done by wounded and discharged soldiers and sailors, June 20th to June 27th 1917, London 1917: Dryden Press

- Kimball, Jane A.: Trench art. An illustrated history, Davis 2004: Silverpenny Press.

- Projektgruppe 'Trench Art, Kreativitat des Schutzengrabens': Kleines aus dem Grossen Krieg. Metamorphosen militärischen Mülls. Begleitband zur Ausstellung im Haspelturm des Schlosses Hohentübingen vom 26. April bis 16. Juni 2002, Tübingen 2002: Tübinger Vereinigung für Volkskunde.

- Reznick, Jeffrey S.: Material culture and the ‘after-care’ of disabled soldiers in World War I Britain, in: Cornish, Paul / Saunders, Nicholas J. (eds.): Bodies in conflict. Corporeality, materiality, and transformation, London 2014: Routledge, pp. 91-102.

- Saunders, Nicholas J.: Trench art. Materialities and memories of war, Oxford; New York 2003: Berg.