The “Religious Fervour” of the Intervention↑

The different faiths in Italy followed analogous paths in relation to the war which erupted in the summer of 1914. Albeit for their own varied reasons, they passed from an appreciation of the government’s initial choice of neutrality to support for intervention. They all welcomed it with an outpouring of religious celebrations that ranged from the divine invocation for the country’s protection and victory to taking up the interventionist rhetoric about the war of redemption, regeneration and restoration of the right of peoples. This phenomenon was particularly evident in the majority of the Catholic population, who were mobilized through the extensive network of parishes.[1] But the minority faiths, too, gave religious expression to their support for Italian participation in the conflict. On 13 June 1915, the Evangelical Churches organized, in Rome, a solemn religious ceremony Pro Patria,[2] and in the following September, participation in the Jewish religious ceremonies of Rosh ha-Shana and Yom Kippur, during which God was asked to make the Italian Army victorious, was particularly high.[3]

Contemporaries gave detailed interpretations of this "religious fervour". For some it was a spiritual rebirth, for others the emergence of deeply-rooted cultural orientations or the expression of an emotional reaction.[4] With the passage of time, the phenomenon was put into perspective and some investigations emphasized its limits. As early as a few months after Italy’s entry into the war, the Jewish press noted that the synagogues in their communities had returned to being deserted and over the following years it reported, with alarm, the phenomenon of the tendency of its soldiers to “merge” with their comrades in arms and put aside their identity.[5] In 1917, Agostino Gemelli (1878-1959), a Franciscan military chaplain, doctor and psychologist, published a book entitled Il nostro soldato (Our Soldier), in which he demonstrated (on the basis of personal observations and data collected from other military chaplains) that the religion of the soldiers at the front was not the expression of an authentic faith, but the result of psychological mechanisms that could be directed to reinforcing their strength and commitment in battle. Gemelli also had an apologetic objective: to show the army and the Italian state the importance of religion in the psychology of the soldier, in order to achieve victory, and in the “national education” of the Italian people after the war.[6]

The Military Clergy↑

The Italian authorities, for their part, were well aware of the usefulness of religion to maintain soldiers’ morale, and optimize their commitment to the war effort. As early as 12 April 1915, before Italy’s entry into the war, one of Luigi Cadorna’s (1850-1928) circulars reintroduced the role of the military chaplain – gradually suppressed between 1865 and 1878 and partially readmitted to the health services in the war in Libya - by establishing the allocation of Catholic chaplains to each regiment.[7] On 2 June 1915, the first Waldensian and Jewish military chaplains were appointed: during the conflict, the total number for both religions was nine (the Waldensians almost all had the rank of second lieutenant and the Jewish chaplains the rank of captain). In January 1918, three military chaplains of the Methodist Episcopal Church were appointed, of which only one was able to carry out his full duties.[8]

The chaplains of the different faiths also worked differently because of their difference in numbers. The Waldensians were normally limited to personal and occasional contacts with individuals or small groups, correspondence and officiating some religious ceremonies.[9] The activity of the Jewish chaplains was mostly directed at maintaining contact between soldiers and their families, making visits to military hospitals, and organizing, for the soldiers, the Jewish religious holidays.[10]

The work of the Catholic military chaplains covered a broader range, because they were so widespread in the various military corps. They were regulated by a decree of the Consistorial Congregation from 1 June 1915, and by the Italian government’s decree of 27 June 1915. The first decree established the figure of the field bishop and appointed to this position the auxiliary bishop of Turin Bartolomasi Angelo (1869-1959), whose jurisdiction extended to all Catholic chaplains, with the exception of six belonging to the Order of Malta, who were dependent on their patron, Cardinal Gaetano Bisleti (1856-1937). The second decree recognized the office of field bishop and assigned him the rank and salary of Major General, while the ordinary chaplain was assigned the rank of lieutenant. The choice of the chaplains was made by Bartolomasi after the acquisition - in accordance with the provisions of the Consistory - of information about the candidates from their relevant religious ordinaries or superiors. The army curia also exerted control on the soldier-priests through four “army curia delegates” posted on different fronts, the military chaplains and the diocesan ordinaries in whose territory military units were deployed.

According to official estimates, 24,446 clergy were mobilized during the war, of which 15,000 were soldiers and 2,400 military chaplains. The latter carried out many functions, ranging from giving spiritual comfort to education. The most strictly religious tasks were celebrating mass in the field, the functions for the repose of the dead, the administration of the sacraments (including general absolution and communion before the fighting), and preaching. The sermons intertwined explanations of the Gospel with reminders of the values of order, discipline, and patriotism. Except in the case of a minority of nationalist chaplains, the preaching was not usually aligned with war-time propaganda, but tried to mould behaviour in the listeners which would be not only patriotic, but also Christian. Therefore, there was an insistence on the necessity of faith and religious practice, the purity of morals and language, and a sense of duty and obedience. The performance of duties by the soldiers was not presented as a constraint imposed from above, but as a spontaneous adhesion, arising from love of the country, which was presented as a Christian virtue. The work of the military chaplains was enhanced by the mobilization of numerous associations in the country - especially evangelical and Catholic ones - engaged in the production and delivery of publications and other materials, which varied from one faith to another, to the armies.[11]

Initiatives in favour of the combatants promoted by the evangelicals covered a very broad range: from the distribution of free newspapers to that of edifying books, Bibles and clothes. Major organizations involved in this area included the Committee for the Moral and Spiritual Support of the Evangelical Military of the Waldensian authority set up in Turin, women's clubs engaged in the work of tailoring, and the Bible Society "Fides et Amor" founded by Giovanni Luzzi (1856-1948). This society printed special editions of the Bible that circulated among the soldiers through the National Institute for Soldiers’ Libraries, the Ministry of Education, the newspaper editors willing to add a New Testament to their magazine, the “Soldiers’ Houses” (recreational spaces for the military largely promoted by Catholics, even though they normally did not have a strictly confessional setting), and the military chaplains.[12]

In a Catholic context, apart from religious pamphlets, edifying magazines and books, devotional material (such as holy pictures and blessed medals) was also distributed. Among the most committed in this activity were the National Committee for the Spiritual and Material Assistance for the Combatants (led by Gilberto Martire and an expression of the Catholic Youth), and the Committee for Religious Assistance of Bologna and Milan. The printed material disseminated by these committees was produced by small publishers (among the most active were the typographical company of Vicenza and, in Milan, the printers of the Holy Eucharistic League, and the Association of Regality of the diocesan curia) and its content was the same as that of the military chaplains’ sermons.[13]

Proposed Religion, Actual Religion↑

The religion proposed by the Catholic chaplains was different from the religion "experienced" by the soldiers. This was expressed in devotional and superstitious practices whose objective was safety and personal salvation and a peace that did not depend upon victory. It resorted to materials from various sources, linked to the most ancient beliefs (such as stones, nails, human remains) and the landscape of war (copper crowns from grenades, bullets extracted from the wounds of comrades) or the Catholic tradition itself (scapulars, blessed laces, medals, alleged relics, rosaries, crucifixes, vials of holy water, medals, holy cards, prayers and votive offerings).

The use of superstitious practices and expectation of miracles were not confined to the soldiers, who in fact drew from the repertoire of popular religious culture in their places of origin. However, the soldiers’ increased exposure to danger led to a particularly intense usage, which the military chaplains tried, in various ways, to curb and direct towards more orthodox forms of religious practice. A significant feature of the difference between the soldiers’ spontaneous religiosity and that proposed by the chaplains was the cult of the saints. A variety of sources (votive offerings, letters and war diaries, journals and bulletins of Catholic organizations and parishes, and the soldiers’ press) attest to the soldiers’ intense devotion, inherited from their places of origin, to the saints and the Virgin Mary. They carried these images on their person, usually accompanied by prayers, and they addressed them in order to receive the grace of safety, thank them for being preserved from death, or ask for an unconditional end to the conflict. They did not have a hierarchy with God at the top, the Madonna in the second position and finally the other saints, but rather differentiated between the divine figures on the basis of a pre-existing personal and family relationship, and the specialty of the miracle of the saint.

The chaplains, however, assigned a marginal role to the cult of the saints and insisted on the observance of the precepts of the Church. They did not fail to refer to some saints, who, however, constituted models of military (as well as Christian) virtue (such as Martin for cavalry, Barbara for artillery, and George for cavalry) or were Italian, among whom only Francis had a certain popularity among the soldiers, rather than the dispensers of graces.[14] The work of the chaplains in correcting the soldiers’ religious practices and behaviour did not simply aim at educating and edifying them. The ultimate and broader objective was, in fact, usually the re-Christianization of the army, society and the state. In this regard, the consecration of the army to the Sacred Heart - promoted by Gemelli and occurring on 5 January 1917 – was significant.

In the text of the act of consecration, the soldiers recognized Christ as their king and asked him to enlighten and direct their leaders (the king and generals) and all the soldiers leading them to victory. They also asked Him to make “our country great and Christian”, to return home not just alive but stronger and more “good”, and to reign over “the whole nation” as well as individual hearts.[15] Therefore, the war was presented as an opportunity both of correction and individual Christian improvement of the soldiers, and of redemption for the nations which had distanced themselves from God. By this act, the army declared that it was Christian and called not only for the victory of the Italian homeland but also for its return to Christianity. The demands of war propaganda were thus combined with a confessional objective which converged with the Pope’s pronouncements about the war. Gemelli’s initiative was not very successful among the troops, and the military authorities forbade not only its repetition, but more generally the public display of the image of the Heart of Christ, inasmuch as it was a sign of a precise denominational characterization incompatible with the unity required at that time.[16]

The Holy See, the War, and Italy↑

From the point of view of the papal magisterium, the problematic nature of the forms of spontaneous religiosity did not only arise at the front and did not only concern their superstitious component. Another problematic aspect was the patriotism of the lay faithful and clergy in the country and especially its expression in cultural terms that threatened (at least in public and official celebrations at which a priest was always present) to demonstrate the commitment of the ecclesiastical institution as such. The question was delicate because it concerned the Catholic Church's relations with the Italian state and the other belligerent states.

A public display by Catholics - and above all by clergy - which was too patriotic would have been appreciated by the Italian state but would have threatened to undermine the line of impartiality in the conflict that the Holy See had stated from the beginning that it wanted to take in the name of Christian universalism.[17] Thus, on 26 May 1915, the Vatican Secretariat of State issued a secret circular to the ordinaries in Italy in which it asked the bishops, and all clergy generally, to avoid promoting ceremonies for the fallen and offering thanksgiving for victories, reserve the solemn Te Deum for the most important ceremonies and, in any case, try to avoid taking part personally.[18]

The Holy See’s call for caution produced a certain distrust on the part of the Italian government towards the Catholic clergy, who were subject to strict control by the police and often accused of defeatism and - above all in war zones - of Austrophilia. Some priests were removed from their seats and there were also allegations of espionage, as in the case of the Pope’s secret chaplain Rudolph Gerlach (1885-1945).[19]

Putting aside the opposing concerns of the Holy See and the government, most of the Italian episcopate supported the war effort, urging Catholics to obey the laws and cooperate with the government and local authorities, especially in the management of charity work related to the state of belligerency.[20] Aside from their patriotic leanings, the bishops sought to mediate between pontifical pressures and those of the nationalist clergy and laity in their respective dioceses.[21] Moreover, they cooperated in giving a meaning to the war and the hardships it involved, encouraging its acceptance by the population. In fact, they labeled it as a divine punishment for the distancing of societies and states from the church and espoused the necessity, for the return to peace, of expiatory sacrifices including the death of soldiers and the innocent in war.[22]

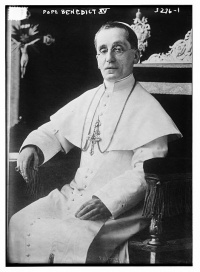

Pope Benedict XV (1854-1922) also saw the war as a result of God's wrath but stated that inverting the process of secularization that had determined it, was a way out, starting from the correction of individual behaviour and the restoration of the Pope’s authority. He tried, therefore, to use the instruments at his disposal to promote such a reversal and hence bring about the conditions he considered necessary to achieve genuine peace.

Among these instruments was worship, which he used, on the part of the Church, as a means not only to pray for God's mercy and obtain a cessation of the conflict “from above”, but also to bring about an inner transformation of individuals capable of translating into behaviour consistent with Christian principles and an open ear to his appeals for peace. He therefore tried to redirect all Catholic prayer in this direction, adapting its interventions to different environments. Thus, he consented to the consecration of the army to the Sacred Heart proposed by Gemelli, in which the invocation of victory - unavoidable in a military context - was associated with the wish for a change in the behaviour of the soldiers and the return of society and the Italian state to Christianity. But in proposing the same devotion to the civilian population, the nationalistic element disappeared and the objective of a return to a Christian society was pursued in two ways: the invocation of greater attention by the people and the heads of state to the papal appeals for peace and the promotion in believers, starting from the family unit (considered the custodian of Christian principles and customs), of a faith which would be more aware, mature and capable of resisting the secularization of contemporary society.[23] Alongside the Church’s religious commitment, there were also the charitable (with assistance initiatives for civilian populations affected by the conflict and prisoners of war, regardless of creed) and diplomatic ones. The exercise of the latter, in particular, was very problematic, especially after Italy's entry into the conflict.

The location of the Vatican on the territory of a belligerent state greatly complicated matters as regards relations with both the host country and those on the opposite side. The situation was further complicated by the nature of the relationship with the Italian state, which continued to be tense for ideological reasons and because of objective circumstances. Ideologically, the Vatican rejected the secular state, and some sectors of the government and some political forces in the country were anti-clerical. On the practical level, there were no official diplomatic relations. On various occasions, the Holy See referred to the jurisdictionalism of Italian ecclesiastical legislation and the censorship of war (which, according to the Pope, seemed, above all, to penalize Catholics) in order to highlight the failure of the Law of Guarantees as a guarantee of its freedom and independence: that is, to give visibility to the Roman Question. In anticipation of this, the Italian government, in signing the secret Treaty of London (26 April 1915), had added a clause (Article 15) designed to exclude the involvement of the Holy See in the peace negotiations, which could have resulted in the movement of the discussion on this issue to an international context.[24]

Conclusion↑

Aside from the fears of the Italian government, there is no doubt that, during the conflict, the Pope tried to act as a supranational moral guide and mediator between the parties in conflict. He employed intense diplomatic activity, to promote peace between the two sides, especially from the summer of 1915 onwards. This culminated in the note of 1 August 1917 in which the Pope called the war a “senseless slaughter”, threatening to deny it the status of a “just war”, and therefore delegitimizing it in the eyes of the people, if the belligerents did not start peace negotiations.[25] The note, negatively received by both sides, gave rise in Italy to a new wave of controversy against the Pope in Italy, which did not even fade when, after Caporetto, the Holy See agreed to the Italian government’s request for the intervention of the bishops and their clergy to support the morale of the people and the army, and facilitate the latter’s military operations.[26]

The hostility to the Holy See, however, was not generalized. Its acquiescence, in various circumstances, to the government and military mobilization in supporting the war-time commitment of the clergy and laity during the conflict had significantly weakened anticlerical views. In fact, until spring-summer 1919, there seemed to be a base for reconciliation and the definition of a common solution of the Roman Question. The political and social tensions inside the country, however, made it slip down the government agenda and it was revisited only under the Fascist regime.[27]

Maria Paiano, University of Florence

Section Editor: Nicola Labanca

Translator: Noor Giovanni Mazhar

Notes

- ↑ Scoppola, Pietro: Cattolici neutralisti e interventisti alla vigilia del conflitto, in Rossini, Giuseppe (ed.): Benedetto XV i cattolici e la prima guerra mondiale, Rome 1963, pp. 95-151, and Prandi, Alfonso: La guerra e le sue conseguenze nel mondo cattolico italiano, ibid., pp. 153-205.

- ↑ Gagliano, Stefano: La Bibbia, i doveri del cristiano e l’amor di patria: il protestantesimo italiano nel primo conflitto mondiale, in Menozzi, Daniele (ed.): Religione, nazione e guerra nel primo conflitto mondiale, “Rivista di storia del cristianesimo”, 3/2 (2006), pp. 359-381, especially pp. 363-364.

- ↑ Toscano, Mario: Ebraismo e antisemitismo in Italia. Dal 1848 alla guerra dei sei giorni, Milan 2003, p. 117.

- ↑ Prandi, La guerra e le sue conseguenze 1963, pp. 173-174.

- ↑ Toscano, Ebraismo e antisemitismo 2003, p. 117.

- ↑ Gemelli, Agostino: Il nostro soldato. Saggi di psicologia militare, Milan 1917, pp. 19-23.

- ↑ Morozzo della Rocca, Roberto: La fede e la guerra. Cappellani militari e preti-soldati (1915-1919), Rome 1980, pp. 7-10.

- ↑ Rochat, Giorgio: Note sui cappellani evangelici 1911-1945, in Id. (ed.), La spada e la croce. I cappellani italiani nelle due guerre mondiali. Atti del XXXIV convegno di studi sulla Riforma e i movimenti religiosi in Italia (Torre Pellice, 28-30 agosto 1994), “Bollettino della società di studi valdesi”, 112/176 (1995), pp. 151-162, especially pp. 155-158.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 153.

- ↑ Pavan, Ilaria: «Cingi, o prode, la spada al tuo fianco». I rabbini italiani di fronte alla Grande Guerra, in Menozzi (ed.), Religione, nazione e guerra 2006, pp. 335-358, especially p. 348.

- ↑ Morozzo della Rocca, La fede e la guerra 1980, pp. 9-14, 45-55 and 79-93, 125-138.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 36-38 and Pluviano, Marco: Tempo libero in divisa: le Case del soldato, in Isnenghi, Mario (ed.): Gli italiani in guerra. Conflitti, identità, memorie dal Risorgimento ai nostri giorni, III, II; Isnenghi, Mario and Ceschin, Daniele, (eds.): Dall’intervento alla «vittoria mutilata», Turin 2008, pp. 704-710. Regarding evangelical associations cf. Gagliano, La Bibbia, i doveri del cristiano 2006, pp. 376-379.

- ↑ Paiano, Maria: Pregare in guerra. Gli opuscoli cattolici per i soldati, in Menozzi Daniele/Procacci Giovanna/Soldani, Simonetta (eds.): Un paese in guerra. La mobilitazione civile in Italia (1914-1918), Milan 2010, pp. 275-294.

- ↑ Stiaccini, Carlo: L'anima religiosa della guerra. Testimonianze popolari tra fede e superstizione, Rome 2009, pp. 99-144.

- ↑ Cited in Lesti, Sante: "Per la vittoria, la pace, la rinascita cristiana". Padre Gemelli e la consacrazione dei soldati al Sacro Cuore (1916- 1917), in “Humanitas”, n. s., LXIII/6 (2008), pp. 959-975, especially p. 959.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 973-974.

- ↑ [Benedetto XV], La Chiesa e i suoi ministri nell’ora presente, in “L'Osservatore romano”, 7 October 1914.

- ↑ Vatican Secret Archives, Rome, Secretariat of State, War (1914-1918), File 63, n. p. 6813.

- ↑ Bruti Liberati, Luigi: Il clero italiano nella Grande Guerra, Milan, pp. 32-40, 138-157, 169-189; Pollard, John: Benedict XV and the Pursuit of Peace, London 1999, pp. 103-107.

- ↑ Monticone, Alberto: I vescovi italiani e la guerra 1915-1918, in Benedetto XV, i cattolici e la prima guerra mondiale, Rome 1963, pp. 627-659.

- ↑ Malpensa, Marcello: Religione, nazione e guerra nella diocesi di Bologna (1914-1918), in Menozzi (ed.), Religione, nazione e guerra 2006, pp. 383-408; Caponi, Matteo: Una diocesi in guerra: Firenze 1914-1918, in “Studi storici”, 50/1 (2009), pp. 231-251.

- ↑ Malpensa, Marcello: I vescovi davanti alla guerra, in Menozzi/Procacci/Soldani (eds.), Un paese in guerra 2010, pp. 295-315. On the origins of this vision of the war Menozzi, Daniele: Ideologia di cristianità e pratica della “guerra giusta”, in Franzinelli, Mimmo and Bottoni, Riccardo (eds.): Chiesa e guerra. Dalla “benedizione delle armi” alla “Pacem in terris”, Bologna 2005, pp. 91-127, especially pp. 91-120.

- ↑ Menozzi, Chiesa: Guerra, pace nel Novecento, Bologna 2008, pp. 15-47, especially pp. 15-36.

- ↑ Pollard, Benedict XV 1999, pp. 85-122.

- ↑ Menozzi, Chiesa, guerra, pace 2008, pp. 36-47.

- ↑ Pollard, Benedict XV 1999, pp. 129-139.

- ↑ Ibid., 162-189.

Selected Bibliography

- Liberati, Luigi Bruti: Il clero italiano nella Grande Guerra, Rome 1982: Editori riuniti.

- Menozzi, Daniele: Chiesa, pace e guerra nel Novecento. Verso una delegittimazione religiosa dei conflitti, Bologna 2008: Il Mulino.

- Menozzi, Daniele: La Chiesa e la guerra. I cattolici italiani nel primo conflitto mondiale, in: Humanitas 6/63, 2008, pp. 889-992.

- Menozzi, Daniele (ed.): Religione, nazione e guerra nel primo conflitto mondiale, in: Rivista di storia del cristianesimo 3/2, 2006, pp. 305-422.

- Menozzi, Daniele / Procacci, Giovanna / Soldani, Simonetta (eds.): Un paese in guerra. La mobilitazione civile in Italia, 1914-1918, Milan 2010: Unicopli.

- Morozzo Della Rocca, Roberto: La fede e la guerra. Cappellani militari e preti-soldati (1915-1919), Rome 1980: Studium.

- Pollard, John F.: The unknown pope. Benedict XV (1914-1922) and the pursuit of peace, London 1999: Geoffrey Chapman.

- Rochat, Giorgio (ed.): La spada e la croce. I cappellani italiani nelle due guerre mondiali. Atti del XXXIV convegno di studi sulla riforma e i movimenti ereticali in Italia (Torre Pellice, 28-30 agosto 1994), in: Bollettino della Società di Studi Valdesi/176 , 1995.

- Rossini, Giuseppe: Benedetto XV, i cattolici e la prima guerra mondiale. Atti del convegno di studio tenuto a Spoleto nei giorni 7-8-9 settembre 1962, Rome 1963: Edizioni 5 Lune.

- Stiaccini, Carlo: L'anima religiosa della Grande Guerra. Testimonianze popolari tra fede e superstizione, Rome 2009: Aracne.

- Toscano, Mario: Ebraismo e antisemitismo in Italia. Dal 1848 alla guerra dei sei giorni, Milan 2003: F. Angeli.