Bishops↑

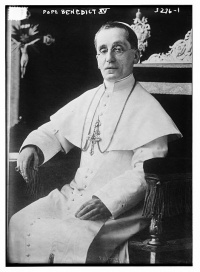

Following in the footsteps of Pope Pius X (1835-1914) and Pope Benedict XV (1854-1922), as well as an ancient theological tradition, Italy’s bishops interpreted the 1914 outbreak of war as a punishment sent by God for the sins of individuals and nations, and most particularly for the sin of secularism. Consequently, they called on Italians to repent and sacrifice. The first response of Italy’s bishops to the war’s eruption was, therefore, a spiritual mobilization.

As soon as Italy entered the war in May 1915, the bishops aligned themselves with the state, holding that only the Italian government had the right to determine whether Italy’s war against the Austro-Hungarian Empire met the conditions of a just war. In line with this principle, the people – first and foremost, Catholics – had no choice but to accept the government’s decision. Some bishops went further and steadfastly defended the justness of Italy’s cause. Echoing the claims of democratic interventionism, they alleged that Italy was fighting for the liberation of the terre irredente (unredeemed lands). This was the case, among others, of Cardinal Pietro Maffi (1858-1931), archbishop of Pisa, who soon became the symbol of the new alliance between faith and nation.

For Italy’s bishops, sacrifice for the country was a religious duty as well as an act of charity and brotherly love. Despite this conviction, however, they did not share Cardinal Désiré-Joseph Mercier’s (1851-1926) opinion that dying for one’s country was, in itself, a sufficient guarantee of eternal life. From their perspective, only the soldiers who died in a state of grace secured the salvation of their soul. This was the key argument of Monsignor Nicola Monterisi (1867-1944), bishop of Monopoli, in his 1917 Pastoral Letter for Lent. This letter was deemed so instructive that it went through at least eight Italian and two translated French editions by the end of the war.

Finally, Italy’s bishops played a central role in civilian mobilization, as well as in assistance and charities. Seminaries and other ecclesiastical spaces were used as hospitals and even military headquarters; special committees were established on a diocesan level to help prisoners (and their families), widows and refugees, especially after the Battle of Caporetto.

Chaplains↑

Between 1865 and 1878, chaplains in the Italian army were progressively reduced in number as a consequence of the conflict between the new Kingdom of Italy and the papacy. Partially in contrast to this trend, in 1911-1912 roughly twenty chaplains accompanied the Italian troops to Libya. This small number is attributable to the government’s decision to reintroduce chaplains only in health services, and not in combat units. On 12 April 1915, the chief of staff of the Italian army, General Luigi Cadorna (1850-1928), assigned a Catholic chaplain to each regiment in preparation for war. Cadorna’s main concern was to use chaplains as a means to instil discipline and obedience. By the end of the war, Catholic military chaplains reached 2,624 in number. Together with the other 24,446 ecclesiastics serving as soldiers (priests, seminarians and members of a religious institute), they were subject to the ecclesiastical authority of a field bishop, Monsignor Angelo Bartolomasi (1869-1959). The Italian Supreme Command also nominated nine Jewish, nine Waldensian and three Methodist military chaplains.

With few exceptions, the words and deeds of the chaplains of all creeds met the expectations of the chief of staff of the Italian army. They did not limit themselves to religious assistance, but also taught sacrifice for one’s country as a religious duty. Due to their number, the Catholic military chaplains covered the broadest range of activities. They celebrated Mass, administered the sacraments (relying also on the specific practices of ministry on the battlefield, such as general absolution), preached the Gospel, buried soldiers, distributed cigarettes and other care package items, and managed the Case del Soldato (Soldiers’ Homes), places where soldiers were entertained and also taught to read and write.

From the perspective of the Catholic military chaplains, the war provided an extraordinary opportunity to re-Christianize society, not only by promoting contact between clergy and soldiers, but also by demonstrating the individual and social resources of Catholicism – in particular, moral support and consolation on the one hand and a sense of duty and social order on the other. In this regard, the attitude of the Catholic military chaplains to the First World War was a complex combination of religious assistance, patriotism and apology.

Sante Lesti, Scuola Normale Superiore

Section Editor: Marco Mondini

Selected Bibliography

- Cavagnini, Giovanni: Per una più grande Italia. Il cardinale Pietro Maffi e la Prima Guerra Mondiale, Pisa 2015: Pacini editore.

- Lesti, Sante: Riti di guerra. Religione e politica nell'Europa della Grande Guerra, Bologna 2015: Il Mulino.

- Malpensa, Marcello: I vescovi davanti alla guerra, in: Menozzi, Daniele / Procacci, Giovanna / Soldani, Simonetta (eds.): Un paese in guerra. La mobilitazione civile in Italia, 1914-1918, Milan 2010: Unicopli, pp. 295-315.

- Morozzo Della Rocca, Roberto: La fede e la guerra. Cappellani militari e preti-soldati (1915-1919), Rome 1980: Studium.

- Pignoloni, Vittorio: I cappellani militari d'Italia nella Grande Guerra. Relazioni e testimonianze (1915-1919), Cinisello Balsamo 2014: Edizioni San Paolo.