Political Goals↑

The German Ober Ost (Oberbefehlshabers der gesamten deutschen Streitkräfte im Osten) administration of the First World War differed from other occupation authorities, such as those established in Warsaw or Brussels, particularly in the absence of a civilian rule. This special situation was due to the political intents of the leading Ober Ost figures and later heads of the Third OHL (Oberste Heeresleitung), Supreme Commander Paul von Hindenburg (1847-1934) and his chief of staff, Erich Ludendorff (1865-1937).

While government and parliamentary circles aimed to seize control of the German occupation policy in Eastern Europe and install an informal rule over the former western provinces of the Tsarist Empire, the military leaders, backed by conservative and nationalistic pressure groups, preferred an extra-constitutional “military state”.[1] This settlement colony was supposed to balance any democratic trends in the German Empire in the long run. As dukedoms or kingdoms, the Baltic Provinces and Lithuania were to be linked to Germany only in the form of a personal union, conducted by Wilhelm II, German Emperor (1859-1941) himself. In this way, any influences of democratic institutions were to be contained.

Cultural Mission and Economic Plunder↑

Like comparable colonial projects overseas, Ober Ost could be seen as an experimental field, where the native inhabitants in particular were used as test objects for new societal ideas. The German self-definition of Ober Ost interior politics as a cultural mission ("Kulturmission")[2] and the massive use of force towards the different ethnic groups, including notably the Eastern European Jews, emphasize this impetus.

Despite these efforts to create a model colony, a main function of Ober Ost was to supply not only the eastern armies with food and goods but also to help the home front with any type of raw materials needed. Forced labour and requisitions caused thousands of deaths, destroyed the local economic base and undermined all attempts to win the population.

Internal Structures↑

The Ober Ost territory reached its largest size after the German advance in March 1918, when German forces conquered Livonia and Estonia from the Red Army. Between the autumn of 1915 and 1917, the Eastern Front was characterized by a relative balance of power between the Russian Empire and the Central Powers. During this time, the German frontline ran from south of Riga in the north to the Rokitno Marshes in the south. The main Ober Ost territories included about 110,000 square kilometres with a population of approximately 3 million inhabitants.[3]

After the first great gains of territory in the summer offensive of 1915 and the conversion of Congress Poland into a civilian governorate, Ludendorff transformed the different army administrations into permanent local occupation authorities. After several rearrangements, three great districts, subjected to one respective army major, were formed: the German Military Administrations (Deutsche Militärverwaltung) of Kurland, Lithuania and Bialystok-Grodno.

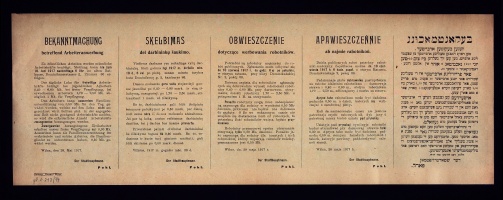

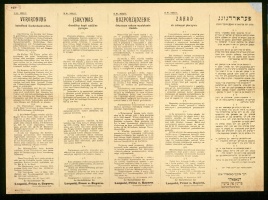

Each of these districts were divided into smaller counties, led by captain's rank. Rising pressure from the Reichstag and the German government forced Ludendorff to restructure the solely military central administration (Hauptverwaltung) he had created above the district level, and add a civil chief administrator. Different departments (e.g. interior, education, economy) adopted the political ordinances for the district levels and published them in the official law gazette (Befehls- und Verordnungsblatt) of the Ober Ost administration. The code of administrative regulations (Verwaltungsordnung) served as the informal Ober Ost constitution.

Brest-Litovsk and Dissolution↑

During the peace negotiations of Brest-Litovsk in 1918, the right of self-determination became a popular demand that put Hindenburg and Ludendorff’s plans under pressure. Especially the German secretary of state, Richard von Kühlmann (1873-1948), tried to use the growing public interest in Germany’s eastern policy to lend it a more liberal appearance. As a result, the military authorities were forced to ease the strict rule in Ober Ost and allow the corporate bodies (Landesräte) in Kurland and Lithuania, already selected in 1917, to participate in the political discussion. Landesräte were established in Livonia and Estonia in 1918. Since these bodies never reached a serious level of sovereignty, all attempts to bind the emerging Baltic States after the German defeat in November 1918 failed.

Kai-Achim Klare, Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg

Section Editor: Christoph Nübel

Notes

- ↑ Liulevicius, Vejas Gabriel: War Land on the Eastern Front, Cambridge 2000, p. 7.

- ↑ Presseabteilung Ober Ost: Das Land Ober Ost. Deutsche Arbeit in den Verwaltungsgebieten Kurland, Litauen und Bialystok-Grodno, Stuttgart 1917, p. 425.

- ↑ Data differ in relation to the adopted outline, ibid., appendix.

Selected Bibliography

- Liulevicius, Vejas Gabriel: War land on the Eastern front. Culture, national identity and German occupation in World War I, Cambridge 2000: Cambridge University Press.

- Presseabteilung Ober Ost, Oberbefehlshaber Ost (ed.): Das Land Ober Ost. Deutsche Arbeit in den Verwaltungsgebieten Kurland, Litauen und Bialystok-Grodno, Stuttgart; Berlin 1917.

- Strazhas, Abba: Deutsche Ostpolitik im Ersten Weltkrieg. Der Fall Ober Ost 1915-1917, Wiesbaden 1993: Harrassowitz.

- Westerhoff, Christian: Zwangsarbeit im Ersten Weltkrieg. Deutsche Arbeitskräftepolitik im besetzten Polen und Litauen 1914-1918, Paderborn 2012: Schöningh.