Early Years and First World War↑

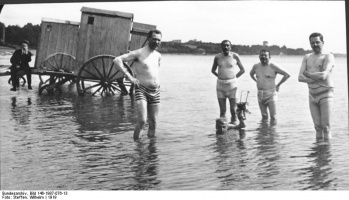

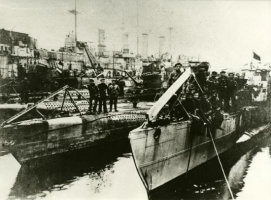

Gustav Noske (1868-1946) was born to peasant-craftsmen parents. In 1882, he began a four-year apprenticeship as a basket maker at the Reichsteinische Kinderwagenfabrik, likely influencing his identification with the labour movement. This was not unproblematic, due to the ruling anti-socialist legislative power. Early in life, Noske helped to develop a social democratic movement and took a stand for the renewal of unionization when he consolidated the basket makers’ trade union. He gained prominence in the labour movement after the so-called Anti-Socialist Law (1890). At the age of twenty-four, Noske became chairman of the Social Democratic Association in Brandenburg. Later, he was elected to the Reichstag, where he was considered an expert on naval and army affairs and occupied himself with colonial matters. In 1912, he became co-speaker for the naval budget and advocated for the approval of war loans. He travelled to Belgium in the opening months of the First World War and defended the conduct of German soldiers against accusations of atrocities. Subsequently, he visited troops on the front as often as possible, travelling to the Belgian and French front in 1914, and paying several visits to ships and submarines as well. Though he never served as a soldier himself, between 1914 and 1916, Noske spent a total of fifteen weeks at the front. He worked as a war correspondent and recommended war credits.

The Revolution↑

In November 1918, Noske was ordered to prevent a shipyard workers’ strike in Kiel. After his election as the spokesman and leader of thousands of sailors, he was appointed chairman of the Workers and Soldiers Council there, and later, governor of the Kiel sailors. A short time later, on 28 December, Noske became the national commissioner for the army and navy. This period was later referred to by historians as “the era of Noske” because of the influence he exercised up until the Kapp Putsch in 1920. Charismatic and powerful, Noske was perceived as a “strong man of his time” even by his contemporaries.

Noske became a controversial figure at the beginning of 1919 during the January Uprisings. His support for strong military and violent action earned him the nickname “Bluthund” (bloodhound). Granted far-reaching powers to suppress the protestors’ occupation of the Vorwärts newspaper offices, Noske was seen as a counterrevolutionary. Tasked with restoring order in Berlin with the help of the Freikorps volunteers and additional military support, Noske was able to march into Berlin with 3,000 men on 11 January. He occupied Moabit and other parts of Berlin and, after the general strike and riots in the city, he enacted the so-called Schießbefehl on 9 March, allowing military forces to carry out summary executions. Over 1,200 people lost their lives during the uprising.

In February, Noske was appointed Reichswehrminister in Philipp Scheidemann’s (1865-1939) cabinet, but was forced to resign after the Kapp Putsch because of his violent counterrevolutionary history. His case illustrates a key problem in the young Weimar Republic: on the one hand, officers from the old military, bolstered by an enormous number of Freikorps troops, gained power over domestic politics, while on the other, the government failed to recruit armed socialist democratic workers to restore order.

Late Years↑

In 1920, Noske became governor of the Prussian province of Hanover, and the rest of his political career was seen as a decline. During and after the National Socialist takeover, Noske was able to remain in his post until September 1933, and was then dismissed due to the law of the restoration of the professional civil service.

Noske’s legacy has been highly contested. His critics remembered him as the “bloodhound” or “bloodnoske,” lambasting him for his commitment to military action and his role in the murders of Rosa Luxemburg (1871-1918) and Karl Liebknecht (1871-1919) – it is debated whether Noske approved of the murders, but it is certain that he aided the protection of the accused after the event. On the other hand, his supporters continue to argue that he was a strong man and a talented speaker who protected his country from revolution. Noske died in Hanover in 1946.

Julian Aulke, Georg-August-Universität Göttingen

Section Editor: Mark Jones

Selected Bibliography

- Aulke, Julian: Räume der Revolution. Kulturelle Verräumlichung in Politisierungsprozessen während der Revolution 1918-1920, Stuttgart 2015: Franz Steiner Verlag.

- Bode, Günther: Gustav Noske als Oberpräsident der Provinz Hannover 1920-1933. Anmerkungen sowie Quellen- und Literaturverzeichnis, volume 2, Karlsruhe 1982: Rohrkirsch/Fischer.

- Bode, Günther: Gustav Noske als Oberpräsident der Provinz Hannover 1920-1933. Textband, volume 1, Karlsruhe 1982: Rohrkirsch/Fischer.

- Jones, Mark: Founding Weimar. Violence and the German Revolution of 1918-19, Cambridge 2016: Cambridge University Press.

- Köster, Adolph / Noske, Gustav: Kriegsfahrten durch Belgien und Nordfrankreich 1914, Berlin 1914: Vorwärts.

- Noske, Gustav: Erlebtes aus Aufstieg und Niedergang einer Demokratie, Offenbach 1947: Bollwerk-Verlag.

- Noske, Gustav: Von Kiel bis Kapp. Zur Geschichte der deutschen Revolution, Berlin 1920: Verlag für Politik und Wirtschaft.

- Wette, Wolfram: Gustav Noske. Eine politische Biographie, Düsseldorf 1987: Droste.